Not Fast Food, Women!

Alina Marazzi's film, We Want Roses Too, juxtaposes found footage with personal narratives in a hommage to the struggles of Italy's sexual revolution. In her review, Agnese Trocchi points out a broader purpose: to unify today's solo-fighting woman with her activist mothers, aunts and grandmothers of radical past

How would women of the '60s react if they had a chance to see through the thick curtains of the future? ‘Curiosity, you are a woman', declares the first sequence of Vogliamo Anche Le Rose, or We Want Roses Too, a documentary by Alina Marazzi portraying the profound changes brought about by the sexual revolution and the feminist movement in Italy during the '60s and '70s.

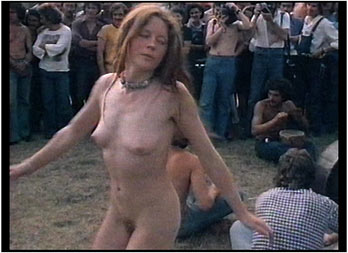

The short comical sketch ‘Curiosità' by Nino and Alfredo Pagot, depicts a woman entering a curiosity store. There she looks into a crystal ball and sees the future embodied in a girl who dances naked in a park. The park is Parco Lambro, the year in the future is 1976. The girl dances at the third iteration of the Festival of Youth Proletariat, organised by the magazine Re Nudo. It was a point of no return for the Italian movement of the '70s because it was here that political and creative souls clashed, and the contradictions between organisation and chaos emerged. Alberto Grifi, one of the fathers of video activism, bore witness to the festival in his films Anna (1975) and Parco Lambro (1976)

Alina Marazzi uses Grifi's footage along with material from the film-makers of the '60s to compile her journey through the 20 years that changed our lives. When the woman of the '60s faces her future in the crystal ball, her expression turns to one of horror as she witnesses the pagan aspect of femininity exposed in public - a shocking challenge to her fundamental beliefs. She lives in an age in which women aren't supposed to express their pleasure and their sexuality. Just 40 years ago the duty of a woman was to find a good husband and be a good wife. But how would our woman react if she could see a little bit further into the future; what if she had the chance to extend her gaze into our present moment? The pagan dancing girl may turn into a half-naked sex doll wandering through the rooms of a fancy house in which anyone can peep, just by turning on the TV. Behind the curtains of time the film of Marazzi questions our own lives as women today: where are we now and where do we want to go?

Marazzi takes us on a trip into the inner lives of three young Italian women between the '60s and '70s. Three diaries of three very different girls in three very different years: Anita in 1964, Teresa in 1975 and Valentina in 1979. The decision to narrate a historical period through the feelings of a person finds its explanation in the director's previous works. Marazzi's first movie, Un ora sola ti vorrei [For One More Hour With You], is made up of family footage filmed by her grandfather, and the story unfolds through the personal diary of her mother who committed suicide in 1972 when Alina was six years old.

In her most recent work Marazzi moves from her intimate story to the broader social context in which the experience of her mother took place. The conditions of her mother's life were shared by many women across those decades. In We Want Roses Too, three personal diaries interweave a storyline into which many voices are heard. There are the wives going to evening school to gain a different life from the one they have. A woman engaged in homework declares that girls don't know what to expect after marriage, they have no choice. The thoughts of Anita in the first diary call into question the inevitability of marriage. She feels she has no alternative. ‘How can we live outside of the social stereotypes?' she wonders. Anita is a girl deprived of her sexual impulses by a repressive family and education. In her words, we hear the desperate whispers of thousands of women posing the same questions about love, sex and life. The director helps us understand how the feminist movement was born from the deep womb of all the women of the past. The sexual revolution took place first in women's consciousnesses, only later becoming a mass movement.

A few years later, Teresa, a girl living in the repressive south of Italy, has very different experiences. She is in love, sexually active and has a strong relationship with her body. And it's in her body that she has to face the experience of an abortion. She is involved with a feminist collective and suddenly the question of abortion is no longer an abstract cause but a naked and cold reality. She travels to Rome from Bari for a clandestine operation, and she realises that she doesn't have the right to choose. The family culture in which she grows up brings her to a forced decision. Marazzi brilliantly connects us to Teresa: the images of a boat sailing in the ice speak loudly for her. The experience of Teresa illustrates that abortion is a trauma and that a woman's choice should be respected by society.

But it's in the words of the third diary that we understand how much is left to do and to fight for if we are to see the seeds sown by those 20 years of struggle begin to bloom. Valentina, a woman active in the famous feminist Roman circle, Il Governo Vecchio, reflects on the movement and on her life, and feels that both men and women are defeated. The goals that they have been trying to achieve during the sexual revolution are far from being realised, and a great deal of work on human consciousness is still to be done.

We Want Roses Too is not a history of feminism, but a record of social history. Where have these women come to rest today? If the curious woman conjured by the Pagot brothers was scared of her image in the future would the women of the '70s be scared of their daughters and nieces, the young women of today?

Image: Girls at the border of pubesence and childhood.

A month before the movie's release, on 12 February 2008 in Naples, a woman was arrested and charged with homicide after undergoing a therapeutic abortion. ‘Therapeutic abortion' is allowed under the Law 194 if the pregnancy has passed the legal 90 day limit for voluntary termination, and it's possible to undergo it when the health of the woman or of the foetus are under threat. This woman was arrested in her hospital room directly after the abortion. An anonymous caller told local police that the hospital was performing an illegal abortion. That was not the case, but the woman had to suffer the interrogation of policemen when she was recovering from surgery. It was just one amongst many assaults against the bodies of women, and against the Law 194 that legalised abortion in 1978.

Italy is ruled by the moralist power of the Catholic church and a woman's right to make decisions over her body is continually under attack. Only a few days before this event, a middle-aged married woman had spoken out about the pharmacist-cum-conscientious-objector who had prevented her from buying the morning-after pill. Men, once again, want to control women's consciences. We'd had enough and, on 14 February 2008, women's circles all over Italy organised demonstrations in every city. I felt the urge to participate and went to the sit-in in front of the Department of Health in Rome. When I arrived there were around 300 women. Two ladies about 50 years old came over to interview me for their online women's journal. They were excited because it was the first time they had made interviews for the internet. They were interested in me because they saw me as young, but when I told them my age they seemed disappointed; I'm 36 and I'm one of the ‘younger' ones. What has happened to the next generation? I look around and the average age is 50. There is an old lady with her old mother, who is about 80 years old. There are women of my age with their kids but a whole generation is missing.

What happened to the girls? They take advantage of their rights but don't believe in street action and demonstration. They don't believe in collective experience and they try hard, on their own, to find their space in society. I was one of those who grew up with the social rights - abortion, divorce, sexual equality in workplaces -that had been acquired by the previous generation, and thought that it would be impossible for them to be questioned again. I was wrong - these rights still need to be defended. As Valentina wrote in her diary 30 years ago, these rights are not yet metabolised by society. Women achieved the freedom to pursue a career but at the expense of their emotional lives, or with an excess of stress on their shoulders. A woman should be everything, a mother and a worker at the same time; there is no role model to follow, and girls have lost the importance and the pleasure of being together with other women. We are all in the middle of the crossing. ‘When the wife is happier, the husband is happier too', says a man in the kitchen, talking about his wife. She goes to evening school and the quality of their life has improved. But after 30 years, things are not so easy. ‘We're defeated, both men and women, after '77. I think the real effects will be slow to install in our consciousness.'

Image: The image of the future inside a crystal ball

In that critical moment, when the propulsive forces of the revolution had been exhausted, society was fragile and naked. It was the moment to entrench new understandings. But a new factor was introduced, bringing the brutal force of the market into everyone's homes. The television era was just starting. In the '80s, the ruthless rise of Mediaset private TV channels in Italy introduced the image of woman as the perfect product into the delicate social body. Women undress as a sign of freedom, but this freedom has been abducted and used against them. The winning model today is the high-achieving female who makes it in show business using her body. More and more girls attempt to be seen on TV, no matter how. They assume they are in control but they are not. They think that the battles of feminism have been won and that they are strong enough to play with symbols and signs of submission. Teenagers plan the shapes of their bodies as if they are engineering a product for the market, and surgery seems a means of freedom. But we should question where the image of the perfect woman comes from. Huge tits, inflated lips, skinny bones, forever young. The real woman has disappeared from the public scene.

Marazzi's movie shows us documents from 30 years ago. There are social enquiries, interviews, family films and events where we see a great number of real women who are all very different from each other, younger and older, expressing a beauty that comes from their identities, their wrinkles, their imperfections. Watching the movie you may fall in love with some of them. They are the worker in the car factory, the housewife of the south who is Catholic but uses the pill and wants to talk about it to the Pope, the Sicilian woman who isn't feminist because it's not the fashion there in Sicily. The girl in Parco Lambro who fiercely discusses the right to fuck when she wants and with whom she wants without being understood as ‘bourgeois' for doing so. At the end of the movie you feel a vague nostalgia for something that has been lost. If you switch the channels on your remote control you realise what we are missing. We lack the faces of the women, we lack the difference, the instability of beauty. We are in a society where the canons of beauty are given by the men in power and slowly delete our individuality. As with the standardisation of food in the global market, the differences are being erased. In the future there won't be the ‘other' but only the reassuring ‘same'. Women in this perspective should become an extension of men.

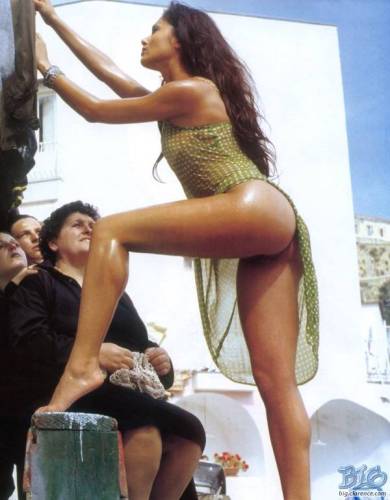

The Commission for Equal Opportunities in Italy was instituted in 1984. Now there is a Department for Equal Opportunities which today, under the Berlusconi government, is directed by Mara Carfagna, a former calendar girl. The problem does not lie in her being a calendar girl - I dream of the day when we will have a sex worker as secretary for Equal Opportunities when the needs and desires of women will really be put on the table. The problem is that our Minister of Equal Opportunities doesn't care about real women's issues, but, in line with the politics of the government, only takes into account the Catholic value of traditional family. She is not the ‘other', she is the reassuring image of what a woman should be: sexually desirable and obedient.

Image: Mara Carfagna, Italy's Minister for Equal Opportunity

We think that we can play with symbols and stereotypes, but to do it we need an awareness that we are in a state of development. We need to build awareness about sex and pleasure, to play with domination and submission without being dominated or submitted to. To be free to choose our lives and to protect the rights that our mothers gained, the young women of the underground movement today push the line of fire forward. They fight for a new kind of family; they are queers, atypical sex workers, different and free, sexually independent and they want to feel pleasure. They imagine the roses they want, and claim them with bio-social technologies.

Sexyshock, in Bologna, was one of the first places where all these issues coalesced. It was founded in 2001 in the context of a squat with the aim of infusing politics and communication with ‘pleasure', ‘sexuality' and that beautiful and revolutionary energy they have. Sexyshock was the first sex shop managed and organised by and for women in Italy and after it many more collectives and shops were born around the country. If the space of Il Governo Vecchio, as we learn from Valentina's diary, was a central place for feminists in the '70s, the places where the new generation of feminists meet today come more from the squat culture than was historically the case. The women of my generation hardly call themselves feminists, but have been fighting for their pleasure and for their right to create their own identity away from stereotypes, using every technological and theoretical means necessary.

Image: Women march for rights in Italy.

Today we find ourselves in the streets again, defending the basic rights to abortion, contraception and equality in the workplace. But we also have to fight a sneakier menace, one that denies the existence of the real woman. A pious and hypocritical ideal of femininity that demands we be the perfect mother, successful professional and commodity to sell in the marketplace of desire. But we are a chorus of whispers and faces, as Marazzi shows with her dense work. We can’t rest on the past but must keep working on the beauty of being ourselves beyond the fast food of bodies.

Info

Alina Marazzi, Vogliamo anche le rose, 2007. Released on DVD with English subtitles 2008.

View the film in clips on Youtube starting with http://tiny.cc/wGCPz

Agnese Trocchi <a.trocchi [AT] incal.net>, artist, writer and videomaker based in Rome, has been active since 1995 in the field of ICT. She has organized and managed international events and projects on the topic of independent communication. In 1999 she co-founded CandidaTV, a small sized media cooperative with focus on creative audio-videos production

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com