Non-Planning for a Change

The freewheeling concept of Non-plan has justified some of the most surprising urban developments. Jonathan Hughes follows its eclectic progress from the late 60s ‘til today.

Who controls the form of the cities around us? Most people would probably consider themselves marginal to the processes which determine the built environment, even though the planning procedures which control development are publicly accountable.

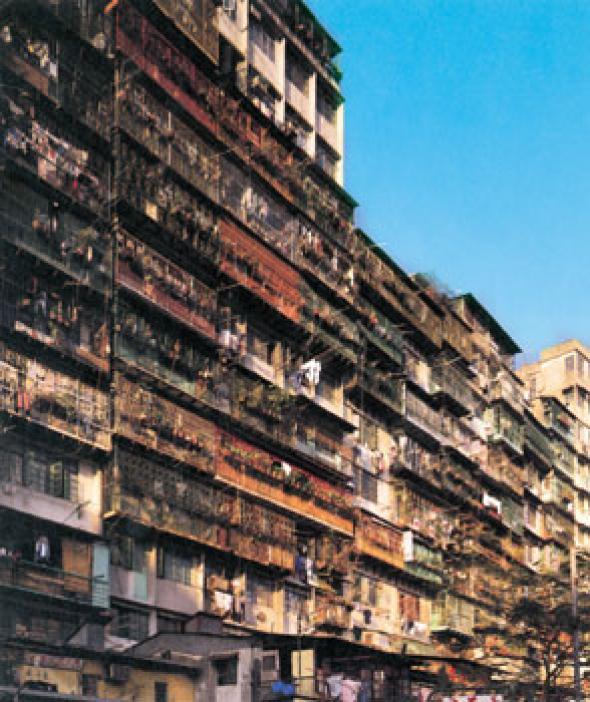

How to short-circuit these processes and hand control back to local communities has preoccupied architects for the best part of the last century. Yet it was not until a New Society article in March 1969 that this imperative had a name: ‘Non-Plan’. Jointly penned by critic Reyner Banham, New Society editor Paul Barker, urban geographer Peter Hall and avant-garde architect Cedric Price, it presented the case for a radical relaxation of planning controls in a series of experimental zones. In this utopian scenario, people would be free to build as they wished without the need for local authority approval. The control of the environment would be transferred from the state to those with the desire to build and with the money and resources to develop.

The article elicited only a small formal response, yet it would re-emerge in countless guises over the coming decades. One of its few original supporters was ex-communist Alfred Sherman, who welcomed the freedoms that Non-Plan espoused. Surprisingly, Sherman would resurface a decade later as one of Margaret Thatcher’s advisors, under whose administration the London Docklands was granted enterprise zone status as a means of scrapping planning bureaucracy and kick-starting regeneration in the decaying Thames-side corridor. Tellingly, the impetus behind Docklands had, in part, come from Peter Hall’s continued support for the relaxation of controls during the 1970s.

But the more technologically adventurous have also allied themselves with the Non-Plan project: the idea of fostering individual control over urban space has overlapped with utopian visions of cheap, mass-produced, pre-fabricated accommodation purchasable off the shelf like clothing, ‘plugged-in’ to the city, and disposed of when no longer fashionable or appropriate. In spirit, if not wholly in practice, this rationale informed the plug-in aesthetics of Richard Rogers’ and Renzo Piano’s Parisian Pompidou Centre and the Lloyd’s Building in the City of London, where facilities and ducts were slung outside the structure of the building, ready to be replaced by cranes mounted on the rooftop.

Although Non-Plan has been elided with laissez-faire free-marketeering or technologically-advanced consumerism other critics, like Colin Ward, have alternatively found in Non-Plan a blueprint for an anarchist urbanism, one which would hand control of the environment back to local communities and local decision making processes. Similarly, on the more liberal fringes of the architectural profession, attempts have been made to promote active community participation in the design process whilst some designers, like Walter Segal, went further and developed self-build schemes to help people design and build their own homes as they wished.

At the beginning of the twenty first century, Non-Plan lives on in all these divergent guises, underlying continuing attempts to engage people more directly in the construction of the buildings and cities around them. The balance of power may not have altered fundamentally, but at least Non-Plan offers a persistent irritant to the professional status quo: a suggestion of alternative approaches and a different prioritisation of agendas.

Jonathan Hughes <Jonathan.Hughes AT capita.co.uk> writes on post-war British art and architecture, and is the co-editor with Simon Sadler of Non-Plan: essays on freedom, participation and change in modern architecture & urbanism, Architectural Press, 2000.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com