Non Event

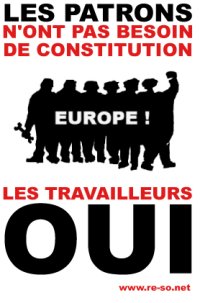

The French vote against the European constitution was hailed by many on the Left as an important ‘social and symbolic’ victory against neoliberal globalisation – and a renewal of political life in France. But, if this refusal of capitalist globalisation took a nationalist form, was it as progressive as claimed?

Yves Coleman, editor of the Paris-based magazine Ni Patrie Ni Frontières, wrote the following critical analysis the day after the referendum. The text is followed by a short Q and A between Mute and the author discussing the possibilities for a truly anti-capitalist dis/engagement with Europe today

As in all electoral competitions, everyone, winners or losers, was thankful for the results of the May 29th referendum. Sure, ‘yes’ supporters are a little put out that ‘la France’ will be, because of the ‘no’, a few years behind in what they call the ‘construction of Europe’. But they can take some consolation in the fact that, after all, they still have power (the UMP, the main right-wing party) or will soon get it back (the Socialist Party). As for the ‘no’ supporters, they are celebrating because Chirac took a gigantic slap. Many think he should have resigned and called for new elections – but this will only and inevitably clear the way for bitter disillusionment, whatever the results.

Both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ supporters all declare that the campaign ‘awakened a new interest in politics,’ that ‘the debate in France was intense among ordinary people,’ there were 'passionate meetings,’ and ‘everybody was studying the Constitution with pen in hand.’ As in each election, but even more visibly so in this case, the participants in the electoral farce are basking in Franco-Frenchness, frequently chauvinistic self-satisfaction, and paternalism toward other Europeans. And what could be more normal, since this is very much one of the functions of the electoral system? That is, to make all the individuals of all social classes of a given State commune in the illusion that they all are equal because they have the same ballot at their disposal. They make believe that, by abandoning their decision-making power to uncontrollable and uncontrolled representatives who do not carry out their commitments or respect their programme, those representatives will act for the general good of the nation – exploiters and exploited all blended together.

But since this election concerned Europe, it is necessary to extend the analysis, not of the results of the vote itself and of the Franco-French politicians’ racket – specialists will do that in the coming months – but of the positions defended by the ‘no’ supporters on the Left, of their mystifying triumphalism and incapacity to form an international and internationalist analysis.  An overall blindness

An overall blindness

To anyone interested in political life in France over the past few years, some things never change. Bourgeois politicians think that their imperialism is still as powerful as it was in the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th; and as for revolutionaries, they seem to act as if the opinion of Marx on the political superiority of the French workers’ movement were still significant a century and a half later, as if we still lived in the period opened by the Revolution of 1789 and closed by the Paris Commune, the period in which the French proletariat might have been the vanguard of other proletariats through its determination to confront the State in 1789, 1830, 1848 and 1870.

Curiously, both conservatives and revolutionaries refuse to see the political consequences of a new reality: France is a militarily declining and economically threatened imperialist power that cannot keep its rank among the capitalist powers without forming tight trans-national economic and political alliances. These alliances are vital for the French bourgeoisie in its European project and this explains why this bourgeoisie is ready to abandon part of its ‘national sovereignty.’

Faced with this situation, revolutionaries have been incapable, during the last 50 years which saw the progressive construction of European institutions, to set up regular connections with their comrades in other countries (Europeans or not), to construct a theory and facilitate action on all the issues: retirement pensions, wages, immigration, police repression, justice, health and education, etc. And when two of the three of the main Trotskyist organisations, Lutte Ouvrière (Workers Struggle) and the Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire (Revolutionary Communist League) have had five MPs in the European Parliament for a legislature, was it of any use? Did these five years of presence inside European institutions help them to prepare a vigorous battle against the constitutional Treaty and its consequences, not only in France but across Europe?

Judging by the absence of collaboration between European revolutionary groups during the year preceding the French referendum and the ‘no’ campaign, it is tempting to answer no to both questions. Anarchists and libertarians in nearly all the countries of Europe, have also been incapable of leading the smallest international campaign against the Treaty or the issues it raises. What are the causes for this lack of internationalism so highly vaunted by Trotskyists and anarchists alike?

This overall political blindness concerning the decline of French imperialism, the incapacity to act and reflect on a European – let alone a global – level, has a fundamental reason: the reactionaries and reformists, and even some on the supposedly ‘revolutionary’ Marxist Left, share the same national lenses fogged by a jacobin universalism and republicanism. For the Marxist Far Left, its French references (from Jaurès to Bourdieu, via Nizan, Bettelheim, Politzer or Poulantzas) are all social-democrat or Stalinist statists. And when they read anything written outside France, they don’t encounter any criticism of the State in the writings of the Bolsheviks or of the ‘heyday’ of the Third International because it was that current which theorised the domination of the Party over the trade unions, the factory commitees, workers councils, the State and the working class.

As for the anarchists, their intellectual references, although not statist, are also primarily Franco-French. Some libertarians relentlessly harp on a past, albeit a rich one (Proudhon, the Reclus brothers, Fernand Pelloutier, George Sorel, Sébastien Faure, Jean Grave, Emile Pouget, etc.), but for which they harbour a distinctly uncritical nostalgia; for many anarcho-syndicalists, it often seems that revolutionary syndicalism before 1914 constitutes a kind of unsurpassable horizon; younger anarchists are frequently attracted by the verbal juggleries and style of the Situationists and neo-Situationists that are hard to count as indispensable in the daily political struggle against Capital, or, when they are eager for new responses, they devour (as do the young Trotskyists), the prose of the statist Left from ATTAC to Bourdieu, without always avoiding the traps of this literature.

As far as I know, even the daily political reflection of the most informed libertarians scarcely appears to draw on current or past analyses made by anarchists in other countries. Very few works by US, Spanish, Argentinian, German, Italian and other anarchists are translated into French, and those that are (Murray Bookchin and Noam Chomsky are without a doubt the most well-known) are hardly brilliant in their radicalism, however interesting they might be. For different reasons, Trotskyist and anarchist French revolutionaries have not done well in distancing themselves from their own histories and their two national traditions, Jacobin and revolutionary syndicalist, respectively.

The ideological depths of both Left and Right: the cult of the State and nation

There exists, whether it pleases them or not to hear this, a national political rhetoric common to both Right and Left, even the Far Left in some cases. In various proportions and in different ways, this rhetoric draws from common themes: the Enlightenment, the universality of the Rights of Man, republican and secular ideology, supposed ‘municipal democracy’, an idealised vision of the Resistance under German Occupation, the myth of the neutrality of the public services and, more recently, the ideology that has grown with the altermondialist movement: ‘participatory democracy,’ and ‘citoyennisme’ (citizenism, the belief that the bourgeois State can guarantee the equality of all citizens), which draws from the French national-statist political tradition and boils down to a blind faith in the lies and illusions of bourgeois democracy.

Of course, all the republicans, partisans of secularism and even citizenists are not chauvinists of the worst variety and their Jacobin-secular universalism also defends some very positive concepts.

But even when they invoke vague internationalist or altermondialist values, they are incapable of breaking practically with the ideology that has taken numerous forms during the history of the class struggle in France. This ideology is based on the cult of the State and its institutions, the belief in its protective, progressive, nearly messianic role, an uncritical relationship with parliamentarianism and other ways of confiscating the will of the people. And over the last few years, the campaigns against the MAI agreement, or more recently, the Bolkenstein directive, has been marked by a disturbing national unity from Right to Left around the theme of the superiority of the ‘French model’, ‘French social model’ or of the ‘French cultural exception,’ themes which reflect a long tradition of which I will give some examples here.

During the Revolution of 1789, the French State claimed to struggle against all the European monarchies and so constitute a progressive factor for the people, and this myth still endures two centuries later, without the Left being able to distance itself from it; under Napoleon, the imperial State claimed to consolidate the Revolution’s conquests by exporting them to Spain, Italy, Portugal, Belgium, etc., with the help of French bayonets; in the 19th century, the Second Empire of Napoleon III tried to play the national unity card and form an alliance between the antagonistic classes, what Marx correctly called ‘Bonapartism’, and Napoleon the Little tried to to contain the Empire’s newly born workers’ movement.

In 1914, the socialist parties and trade unions shamefully capitulated, refusing to call a general strike against World War I, a strike they had talked about for years in their congress motions, and the socialists voted for war credits.

During the 1930’s, Belgian socialist currents (De Man) and French ones (notably Marcel Déat, a ‘neo-socialist’) defended the idea that strong State economic involvement was necessary to handle the international crisis of capitalism and distance the middle class from the call of Fascism. Members of the SFIO (French Section of the Workers’ International, the socialist party), the ‘planistes’ (strong supporters of planning) offered their services to the regime of Marshal Pétain, while others were later involved in the creation of the Common Market (André Philip).

During the Resistance and the government of national unity over which De Gaulle presided between 1945 and1947, there was another version of national unity in the name of the ‘struggle against fascism’ and ‘Let each of us kill a Kraut’ (Communist Party) and then in the name of the indispensable reconstruction of French capitalism (‘The strike is the weapon of the trusts,’ Maurice Thorez, general secretary of the CP).

Since 1945 incidentally, the Left and (Gaullist) Right have joined in evoking the ‘social conquests of the Resistance,’ forgetting the price paid for them – making the workers toil for starvation wages, stuffing the pockets of the bosses and the State for decades and supporting all the colonial and neo-colonial adventures of French imperialism.

Under the Fifth Republic from 1958 to 1969, this cult of the State and its supposed protective and ‘wealth re-distributing’ role grew notably via the economic plans and charisma of DeGaulle, whose anti-US foreign policy was supported by the French Communist Party, the same party that led the repugnant campaign in the 70’s, ‘Let’s produce French’; and during negotiations on the Common Program in the 1970’s and the first two tears of the 1981-83 united Left government, we still had a ‘Left’ version of this national-statist ideology: the nationalisation of some banks, insurance companies and key industries was supposedly going to change the lives of all the oppressed and exploited.

A ‘no’ campaign in which internationalism has been totally absent

In 2005 with the so-called ‘NO of the Left’ campaign, supported by the clowns of the ‘Socialist Party Left’ and part of the altermondialist movement, without forgetting the inevitable LCR, we have witnessed a new blossoming of the statist ideology, clearly evident in their writings and propaganda.

The ‘NO of the Left’ campaign has tolerated or stirred among the electorate and Left sympathisers the most ambiguous forms of anti-US sentiment in the name of denunciations of NATO and the WTO, as well as xenophobic sentiments against:

– the unfortunately famous ‘Polish plumbers’ (it has just been learned after the elections that there were only 150 to 180 of them in all of France);

– the Chinese textile industry (on Monday, May 30, 2005, during a televised report on the European Constitution referendum on France 2 TV, a CGT rep had the cynicism and audacity to denounce ‘Chinese competition’ without once mentioning the fate of 19 million Chinese workers superexploited in their country);

– or the entry of Turkey into the EU (reviving xenophobic, racist and anti-Muslim prejudices).

Faced with this resurgence of nationalist prejudice, the so-called Far Left and the reformist Left chose to turn a deaf ear toward the phenomenon and minimise it because it wanted to surf on the ‘NO of the Left’ wave. Furthermore, it is particularly disgusting to see the Far Left claim the ‘NO of the Left’ had an ‘internationalist’ dimension while it had been incapable, since the strong probability of a referendum was announced, of organising the smallest campaign, even a set of meetings, of revolutionary forces of different EU countries to critique the Constitutional Treaty and explain the real issues for all European proletarians, not only the French ones.

And, considered overall, this ‘no’ vote (there was no means of distinguishing between Right ‘no’ votes and Left ‘no’ votes) was far from internationalist since 42 percent of ‘no’ voters think that ‘there are too many foreigners in France’ compared to 21 percent of ‘yes’ voters. And the National Front (a coalition of far right militants, ultra-conservative catholics and neo-fascists) voters were better mobilised to get out the ‘no’ vote (90 percent) than those of the Far Left.

Today there is no way to differentiate the Left from the No voters: if the Far Left had wanted to, it could have printed its own ballots and massively distributed them during an internationalist campaign. But that would probably have disturbed all electoral conventions.Where did the 6 million votes for Le Pen and de Villiers go?

Far from being a working-class ‘victory’ or ‘the masses’ revenge for Maastricht’ (Alternative Libertaire, Libertarian Alternative), the ‘no’ pseudo ‘victory’ is the progeny of an unnatural alliance between 6 million Le Pen and de Villiers voters (whose xenophobic and racist positions need no further explanation here) with 9 million CP and SP voters (and this estimate is optimistic because it assumes that the traditional Right did not make the slightest contribution to the ‘no’ camp, which is completely inaccurate considering there is a sovereigntist Right). Such a ‘victory’ has nothing to do with defending the interests of the exploited.

What chutzpah (and some scorn, too, for the intelligence of workers) it takes to affirm that the ‘no’ ‘marginalised the Far Right’! These are the same people who explained that it was necessary to vote for Chirac in 2002 because 5 million Le Pen voters represented a fascist danger. Do they want us to believe that these 5 million dangerous voters have today disappeared in a puff of smoke – or withdrawn into their caves, may be? A ‘big symbolic victory’?

The anarcho-electoralists of Libertarian Alternative also naively reveal their lack of political vision when they write, without joking, that the ‘no victory’ is a ‘small social victory’ and a ‘big symbolic victory.’

The anarcho-electoralists of Libertarian Alternative also naively reveal their lack of political vision when they write, without joking, that the ‘no victory’ is a ‘small social victory’ and a ‘big symbolic victory.’

Here is what revolutionaries have been reduced to today – rejoicing at electoral victories, ‘symbolic’ ones at that, or the ‘huge hope’ (LCR) raised by the results of a referendum-plebiscite which turned against Chirac. Incidentally, in their daily propaganda, our revolutionaries hardly talk about destroying the bourgeois State, forming workers’ councils, eliminating the wage system, money and hierarchy, radically reorganizing production and social life. They would rather call for a ‘break with capitalism’ (LCR) just like Mitterrand before 1981 or threatening to ‘make the capitalist tremble’ (Libertarian Alternative). During the Transeuropéennes TV show on Thursday, May 31, Alain Krivine, LCR leader, calmly explained that ‘what the people want is a France of solidarity with full employment and fair redistribution of wealth.’ Well, it’s maybe what ‘the people’ want, but if that’s all the revolutionaries have to suggest to the workers when they have the incredible opportunity to explain their proposals on TV, frankly they would be wiser if they kept quiet rather than serve as mouthpieces for the most moderate proletarians.

As for the ‘other social, democratic, environmentalist and feminist Europe,’ it is only a smokescreen; it is lying to claim that it can be magically found in the ballot boxes and by giving ‘critical’ support to Left politicos.

It is lying to make believe that it could come out of a ‘Constituent Assembly’ with proportional representation, which would give the National Front solid representation with its 5 million voters, without counting all the other reactionary forces that could be unleashed if we remain within the framework of traditional bourgeois democracy. It is lying to affirm that this ‘other Europe’ could come about by holding another European Social Forum, which would only allow all kinds of discredited Left politicians to become born-again virgins.

Far Left militants have very little confidence in the power and accuracy of their ideas to believe that an electoral pseudo-victory could ‘lift the masses’ morale’ (Libertarian Alternative). It was exactly the reasoning as well of the LCR or the OCI (Organisation Communiste Internationaliste, Internationalist Communist Organization, predecessor of the present Workers Party) in 1981 when they explained that the coming to power of Mitterrand was going to raise the hopes of the masses, and that these masses would then ‘outflank the apparati.’ We have seen the result: an exponential increase in unemployment, the decline of the metallurgy, mining, shipbuilding and auto industries and overall degradation of all the so-called ‘public services’, systematic attacks against immigrant workers and blossoming of the National Front and the public expression of racist ideas and behaviour, etc.

The workers who voted ‘no’ are perhaps temporarily happy that they’ve aimed a slap at Chirac and some other representatives of the ruling class. But for the moment, they have NO OTHER POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE than granting power to another part of that same class — the Left that carries out anti-worker policies every time it is in the government. Workers don’t have enough confidence in themselves to take matters into their own hands, taking over the factories and offices, eliminating all hierarchies, shedding themselves of all the repressive forces of the State, putting in place their own power and radically changing all means of production. ‘NO of the Left’ supporters are only reinforcing their illusions about the usefulness and effectiveness of elections, illusions that everyone knows perfectly well – will be betrayed tomorrow.

‘NO of the Left’ manoeuvres

The way the Left explains to us the so-called ‘no victory’ demonstrates once again the incurable nationalism of its leaders. In fact, what did the pseudo-Left leaders of the Socialist Party declare upon learning the election results on Sunday, May 28?

The way the Left explains to us the so-called ‘no victory’ demonstrates once again the incurable nationalism of its leaders. In fact, what did the pseudo-Left leaders of the Socialist Party declare upon learning the election results on Sunday, May 28?

‘I’m proud to be French’ (Henri Emmanuelli)‘Our country has a high conception of politics and rejects an unregulated market economy’ (Marie-Thérèse Lienemann)‘Breaking with capitalism is an empty dream’ (Arnaud Montebourg).

The trio of Dolez-Filoche-Généreux toured France and had about 90 meetings for the ‘NO of the Left.’ They reveled in the ‘buoyancy’ of ‘the French people’ demonstrating in the streets ‘like May 1981’ (in limited numbers anyway). But our three musketeers forgot to mention all the blows suffered by the working class at the hands of the Left in power since those jubilant demonstrations. Loyal to the most arrogant French nationalist tradition, our three ‘Left socialists’ dared to write that ‘the French “no” has created the possibility of an authentic democratic reconstruction of Europe. It lets the rest of Europe know that pro-Europeans have the right to say “no” without threatening the construction of Europe,’ ‘France must provide the impetus necessary for a new renegotiation,’ etc.

Not only do our three crackpots trumpet words like ‘la France’ and the ‘construction of Europe,’ and not only do they reason in the same way as Chirac, still believing that France will be the political head of Europe, but they also deliberately hide the fact that their construction of Europe, whether led by social-liberals or social-democrats, is and will inevitably be an attempt to construct a new imperialist power of unimaginable proportions.

Certainly, we don’t know yet whether this future imperialist power will come into being and with what political institutions it will be endowed, but the EU already has its own money and will someday have its own ultra-modern military, ready to intervene on all continents if it wants to fully carry out its role against US imperialism and the emerging capitalist powers of India, China and other Asian countries.

The SP pseudo-Left has already concocted itself a sweet program: ‘unity of all socialist tendencies, “Left unity” and a new, democratic European constitution.’ In other words, they want to have the catbird seat in the next bourgeois Left government and participate in running European imperialism while giving it a democratic facade.

The Communist Party continues to wallow in its respect for the bourgeois State cult while asking Chirac (Chirac!) to ‘forcefully represent the voice of our people and demand renegotiation of the Treaty through real popular debate in Europe.’

ATTAC has its chauvinism, too, since it proposes a tour of Europe ‘to explain the French “no”,’ as if Europeans were too stupid to understand and have been waiting for the altermondialists to illuminate the issues behind the construction of European imperialism.

In it editorial of Le Monde diplomatique of June 2005 Ignacio Ramonet, member of ATTAC, gives us a perfect example of Left chauvinism: ‘Rebellious France has honored its tradition of a political nation. It has retaken its historic mission. Since its beginning, in 1958, the European construction has exerted a more and more coercive power on all national decisions.’

Altermondialists are right to criticise the reactionary content of the European Constitutional Treaty, but their leaders denounce ‘neoliberalism’ (which is a hypocrite name for capitalism) only in the name of the French nation interests, that is of French imperialism.

A revolutionary attitude would consist not of ‘explaining the French “no”’ to other Europeans but of creating together, with all the revolutionary forces of the continent, analysis and actions to counter the propaganda and attacks of the European ruling classes. But we are far from that... and it is not in any way the objective of ATTAC and the parties of the Left.

The Far Left hawkers of Fabius, Bové and tutti quanti

Faced with the manoeuvres of the crude Left politicians who no doubt plan to put a ‘social-liberal’ (aka bourgeois) like Fabius back in the saddle, the Far Left has basically no plan to suggest other than calling for a Left victory in 2007, while dressing up that call with its usual hypocritical flirtation with a ‘workers’ government,’ ‘an anti-capitalist government’, etc., all formulas that are only code for Union of the Left or Plural Left.

The Parti des Travailleurs (Workers Party) militants have their own committees, but you can be sure that they’ll call for voting CP-SP. Lutte Ouvrière (Workers Struggle) has not immersed itself in the ‘no’ committees, but it too has called for a ‘no’ vote in the referendum and will certainly call for voting CP, even SP, in 2007, as it does in almost every election.

The LCR participated in the ‘no’ committees alongside its opponents from the SP, the Greens and some CP militants. Two days before the ‘victory,’ some LCR leaders were already confiding to Libération that they intended to continue the committees after the elections in order to push the Left into power. And on Tuesday 31 May, faced with accusations of divisiveness by ex-SP minister Moscovici, Alain Krivine could only defend himself by swearing he was ‘1000 percent in favor of unity.’ Okay, but what about anything not related to putting Left politicians in power? By the way, didn’t Clémentine Autain (CP) craftily suggest on Monday 30 May, on L-Télé that it was better not to ‘talk right away about presidential elections in 2007,’ because if ‘we start talking about it, it may destroy the No committees’? What a nice confession that reveals the ulterior motives of all these so-called adversaries of ‘social-liberalism’ with whom the LCR wants to ally itself, supposedly to unmask them later!

The manipulators of the Left and Far Left are slowly going to stir things up with the support of the altermondialists, and maybe even some libertarians, to eventually pull Fabius out of their hat (or why not Bové?) for the presidential elections. But what do workers have to win by betting on those horses? Bitter disillusionment and new vicious blows if they don’t mobilise themselves in their own class interests and ignore electoral Sirens. The struggle will be long and difficult, but it will never happen through the ballot box or the political combinations dangled before us by the Left and Far Left.

A first draft of this text was translated from French by Sonof Tom Joad and later revised by Mute__

Q and A

Mute: Is the situation really as bad as you suggest, or does the ‘no’ vote at least throw up some new opportunities for European opponents of capitalism?

Yves Coleman: This article deliberately takes the opposite view of the dominant official discourse in the Left and Far Left which called in favor of the no. It ‘bends the stick’ in the opposite direction to shatter a milieu which always presents good Left electoral results or one-day national strikes as the first step either towards the return of the Left to power or towards a pre-revolutionary situation.

The aim was also to show that today, more than ever before in European history, the Far Left can’t fight in isolation and think about politics in purely Franco-French terms. A concrete example: French trade unionists, when accused of being anti-European, say that everybody in Europe should earn the same wage. Practically, that’s a nonsense when the minimum wage is 1500 Euros in Luxembourg and 70 Euros in Rumania. That means one has to think European wage claims (and many other ones concerning pensions, Social security, etc.) in common, differentiating between a long-term perspective on a European and even on a world scale and a short term perspective, that should put the stress on workers’ self-organisation, more than fixing perfectly similar concrete demands everywhere in Europe. It is one thing to fight against the European decisions that attack existing rights (like the Bolkenstein directive), a perfectly justified struggle, quite another to pretend that one can immediately win and impose the same rights, wages, social provisions everywhere in Europe. And the victories won in these struggles do not depend on the content of any prettily phrased Constitution or Constitutional Treaty. These will be won only if there is truly revolutionary thinking and practice on a European scale.

French revolutionaries have many difficulties in admitting that the working class in France has been defeated many times during the last 20 years: they forget the disappearance of the mines, steel industry and shipyards, the downsizing of the automobile industries, the attacks on pensions, Social Security, education, etc., that have been led both by Right and Left governments. They seem to think that, because they do not have a Thatcher or a Reagan in front of them, they are better off. This political analysis is wrong and is linked to a traditional over-estimation of electoral politics in France and to the illusions of the Left. That is what enables them to systematically transform lead into gold, presenting electoral victories of the Left – or, in the case of the referendum, a joint victory of part of the ‘left antilibéral’ (ie liberal social democrats opposed to ‘bad capitalist’ downsizing of the welfare state, etc) and the Far Right – as victories of the working class.

Nevertheless, I do recognise that there are new opportunities in the French political situation. Local members of more militant CGT trade unions who fight against the closure of their factories may try to join the ‘no’ committees’ and fuse their struggles in order to better organise resistance to the Right’s current campaign to reform labour laws and impose poorly paid jobs in the name of ‘reducing unemployment’. But these local initiatives will likely have tremendous difficulties in asserting themselves over groups or parties which have their own electoral agenda.

Mute: What about non-statist, sans papiers and other groups who have less interest in pushing a nationalist opposition to the European superstate?

YC: In France it’s very difficult to have grass roots groups or rank and file groups which are truly independent from political parties or grouplets. This is partly linked to the very centralist history of French sovereignty. France was originally just one little island on the River Seine, a kingdom which built itself around Paris, then the Ile-de-France region, and then militarily conquered the rest of the territory now known as France. Most state structures (laws, administration, school system, train network, bank system, etc.) date from the two Emperors — Napoleon I (1804-1814) and Napoleon III (1852-1870) – who centralised French institutions even further.

A political group or a party only exists if it is well represented in Paris. Most groups represented in Paris influence or try to influence all sorts of committees, etc., but they have statist views.

When I say ‘statist’ maybe there is a confusion in the way this word is understood in English: many of these groups may not receive money from the State (although the last ESF was strongly financed by Mr Delanoe, the Socialist mayor of Paris, and several Left mayors of the suburbs who decided to financially support the ESF; and although Trotskyist groups receive one Euro per vote and their electoral expenses are reimbursed if they get a certain amount of votes) but their aim is to receive money from the State, to become a state-financed NGO, or to become part of the State: belonging to State commissions, projects, etc.

What I mean by ‘statist’ and ‘statism’ in this text does not only apply to totalitarian states or ambitious state bureaucrats in western democracies, unanimously condemned by everyone from Right to Left and Far Left. Today the existence of most French NGO’s, daily newspapers, trade unions and political parties depends on state financing. This is officially done in the name of ‘democracy’.

The State, which lives on taxpayers’ money and is supposed to preserve basic freedoms, ‘generously’ redistributes the money it has collected. But in fact the growing financial dependence instituted by state funding has a precise political aim: to create all sorts of mini-bureaucracies which are official or unofficial extensions of the State and regulate the harmonious functioning of capitalist society. If, a century ago, the state could be roughly defined by Engels as ‘detachments of armed people’, the situation is much more complex today, and the openly repressive functions combine very well with many other functions that seem politically neutral and in fact aim to control all dissident individual attitudes.

Activism should be fundamentally based on people’s money and free time, not on state financing. If not, one should not be surprised when young executives volunteer to go and work for NGOs in Afghanistan, partly because it will be a nice reference on their curriculum vitae and help their future career in the public relations industry. Likewise, one should not be astonished when people refuse to give their time and money for a political cause if their expenses are not refunded.

Mute: Are there not other forms of resistance to the ‘neoliberalisation’ of Europe visible in France?

YC: The political parties dominate the social game as well as the trade union bureaucracies. For example, between 1986 and 1995 several more or less temporary ‘Coordinations’ were organised during strikes by postal, rail and hospital workers. These rank and file organisations were much more democratic than the existing trade unions (don'tt forget that French trade unions, including the most reactionary unions, represent only seven percent of the workforce). Ten years later the new-style trade unions which are a direct or indirect consequence of the ‘coordinations’ have fused into a larger Federation called ‘Solidaires’ and have the same problems of internal democracy as the other trade unions (France has several big trade unions: CGT linked to the Communist Party ; CFDT linked to the Socialist Party and left-wing catholics; FO, linked to the Socialist Party and the freemasons, and which, incidentally, has integrated reactionary unions traditionally used as scabs in industrial conflicts; CFTC, linked to the Catholic church, etc.). So, there may be many local committees taking initiatives, but as soon as they unite on a national level they have, up until now at least, fallen into the hands of political or trade union bureaucracies, or remained tiny groups.

Mute: In the UK we have heard some encouraging reports about the European Mayday as a focus for anti-‘precarious’ labour actions

YC: Yes, but these probably do not mobilise more than a few thousand people on a national scale. In France, 4 million people live on less than 500 Euros per month and among these 4 million, 2 million are working on a part-time basis. This wage enables them either to pay their rent or feed themselves and pay their other basic expenses, but not both – especially if it is a family or a single mother with one, or several, children. Precarity is extending but as you know it’s very difficult to mobilise unemployed people or people who have part-time jobs.

I belong to an association that groups together 800 translators, the majority of whom do not earn more than 1000 Euros per month. Even it’s not much, yet we certainly belong to the ‘precarious aristocracy’, and we see everyday how difficult it is to defend people who are in a one-to-one relationship with their employer. And if it’s hard for us, a qualified workforce, it’s a hundred times worse for cleaning staff, supermarket cashiers, McDonald’s employees, etc., who – like us – can be replaced and fired at any time, but who belong to a market where the competition between wage earners is much more massive and intense.

Mute: Are there no signs of a nascent internationalism, however immature, from these quarters?

YC: Internationalism is not a spontaneous feeling. It has to be nurtured by a political culture, discussions, many joint meetings, etc. It needs to mobilise the energy of people who speak several languages, translators and interpreters, etc. It’s a long and difficult process to communicate in several languages, when one comes from different political cultures and even if one belongs to the same political current. For example, being an anarchist in the States is not the same as being an anarchist in France. A Bolivian Trotskyist is not the same as an Italian Trotskyist, even if they belong to the same so-called ‘4th International’, etc.

Internationalism has to correspond to a new vision of Europe, a vision which should break with French bourgeois universalism based on the Declaration of the Rights of Man, and obviously also break with American bourgeois democratic universalism, its main enemy on the world scale. Both have strong national roots even if they have partisans in all sorts of countries who think they have an internationalist view just because they defend the French or the American conception of liberty and democracy.

One of the aims of the Constitutional Treaty strongly influenced by French politicians (many people call it the ‘Giscard constitution’, after Giscard d’Estaing, a former right-wing president of France who originally coordinated the project for writing a constitutional treaty) was to proclaim a new ideology for the European imperialism which is now attempting to appear on a world stage and to give itself coherent political structures.

To develop and create a true internationalism would require from the very start the cooperation of many forces dedicated to acting and thinking at the same time, in the same terms, in different languages. Internationalism is not a collection of left-wing nationalisms. It’s still to be created with new intellectual concepts and means.

The First International may have been closer to what we need today. At that time the process of national integration had not reached the level it attained during the heyday of the Second International, and the militants of the late 19th-century still equated internationalism with a broad sympathy for Enlightment values, the struggle against all dictatorships and Churches. The Second International brought together parties with purely national perspectives, as shown by their almost unanimous pro-war position in 1914. And the Third International was subordinated to its Russian center and State interests. We have to invent a new way of practising internationalism.

BIOG:Yves Coleman <yvescoleman@wanadoo.fr> is a translator and proofreader, former activist in several political groups, and presently editor of the magazine Ni Patrie Ni Frontières, a quarterly journal of translations and debates, published in French since 2002

Ni Patrie Ni Frontières http//: www.mondialisme.org (website shared with other journals)

This publication collects old and recent contributions from different Left traditions (Marxist, anarchist, feminist, etc.). These texts are either translated from various languages (Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, English and Italian – so far) or written by French militants presently engaged in political struggles. The aim is to create a space of debate, each issue being centered around a specific theme (The fate of USSR, Women and Family; Israel/Palestine; Terrorism; Secularism; Trade unions; Nation and States; Wars, etc.). Several booklets about France and about the Netherlands (with the cooperation of De Fabel van de Illegaal) have also been published in EnglishADDITIONAL NOTES AND RESOURCES1. Above all, this article attempts to criticise the analyses put forward by the ‘Left of the No’ and the Far Left, as well as a libertarian group involved in electoral tactics since 2002 (Alternative Libertaire, Libertarian Alternative). The discourse of the latter small organisation reflects the illusions and pressures of a much larger milieu, the Altermondialist-Far Left-Citizenist movement. These pressures were so strong that even sections of the CNT (an anarcho-syndicalist trade union) called for the no, at this last referendum.

The avowed radical anti-statism and anti-nationalism of traditionally abstentionist anarchists (Fédération Anarchiste, CNT, CNT-AIT, OCL, etc.) should have, in principle, prepared them more than anyone else for the serious practice of internationalism, at least at the European level. Reading their press and propaganda shows that they are apparently incapable, and have been so for decades, of building an international network of analysis and action. Not being that familiar with their milieu, I cannot clearly distinguish the most profound reasons for this, but the overall report has been pretty damning ever since the failure of the First International more than a century ago.

2. It is also characteristic that French militants more generally continue to wallow in nostalgia for the May ‘68 movement in France, the radicality and importance of which are so completely reduced when compared with the rich ten years of the Italian Mays or the much more radicalised factory occupations and commissions by Portugese workers during 1974 and 1975.

The self-absorbed ‘68er’ intelligentsia, which became part of the media and political elite of the Left, has strongly influence the vision that the French Far Left has of its own history. Therefore, 40 years later, these militants have not yet integrated into their reasoning the fact that what’s known as ‘the subversive ‘60s’ was in fact begun in the USA and that its most radical peaks appeared in Italy and Portugal. This very much contextualises the historic significance of May ‘68. And if we add to that what happened in countries like Czechoslovakia and Mexico, we can then give the French May ‘68 in more exact and — above all — less chauvinistic proportions.

3. For more information on what is happening in the new EU countries, those who read English will benefit from Prol-position #2: http://www.prolposition.net/ppnews/ppnews2.pdf

Readers will see that a small revolutionary group can do perfectly well in collecting useful info on workers’ struggles in Poland, Romania, Czech Republic, etc., reflecting upon the effect of workers migrating from Eastern Europe on an imperialist power like Germany, for example. Prol-position succeeds in getting past generalisations about ‘liberal’ (aka imperialist) Europe, and does not waste time crafting polemics around the European Constitutional Treaty — polemics which are fit only for constitutional lawyers.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com