No Angels

In two recent books - Web Aesthetics and Interface Criticism - new media critics rescue the sensuality of digital aesthetics from the gnostic grip of communications theory. Review by Charlie Gere

The word ‘aesthetics' comes from the Greek for ‘to sense' or ‘feel', and originally referred to our sensory experience of the world. Most of us spend much of our lives in front of screens, whether at home or work. In the most literal sense, our aesthetic experience of the world is bound up with those screens. Yet the question of the aesthetics of our relationship to media is rarely discussed. Most of the discussions around new media concern questions of production, consumption, dialogue, communication, knowledge and community. The very idea of ‘new media aesthetics' is perhaps thus a kind contradiction since the term ‘media' itself indicates that, new or otherwise, media should have little to do with the whole business of giving us aesthetic experiences. Its proper role should be to convey directly what is supposed to be communicated.

The terms medium and media come from the Latin medius, meaning ‘middle'. The first recorded use of the word ‘medium' in the sense of a ‘means of communicating ideas', in English at least, was by Francis Bacon in 1605 in his The Advancement of Learning. Bacon quotes Aristotle to support his idea of words as a medium. ‘Words are the images of cogitations, and letters are the images of words'. Thus language is the paradigmatic medium, which transparently communicates ideas. In Of Grammatology, Jacques Derrida singles out Aristotle's model of language as an example of logo- or phonocentrism. Although Bacon is widely considered to be one of the fathers of modern scientific method, he was careful not to trespass on what he considered the domains of knowledge proper to God. In several of his publications he suggested that much as the rebel angels fell because they craved power equal to God's, man fell because he desired knowledge equal to God's.

Image: Inside Greg Lynn's Blobwall Pavilion at SciArt gallery during the Venice Biennial, 2008

Nonetheless our model of media can perhaps be thought of as angelic. The term ‘angel' derives from the Greek aggelos meaning, simply, ‘messenger'. Angels are disembodied, pure intelligences (thus not able to enjoy aesthetic experiences). The angelic model of communication still holds sway. Almost all modern information and communications technology relies on the theory of information transmission devised by the American engineer Claude Shannon in the 1940s. Shannon's concerns were to find the most efficient way of encoding a message in a particular coding system in a noiseless environment and to deal with the problem of ‘noise' when it occurred. ‘Noise' was Shannon's term for the elements of a signal that are extraneous to the message being transmitted. For Shannon the ideal system of communication is one in which the mediation of the message, its passage through media, is as untrammelled as possible.

Here one might think of the claims made about the coming world of ‘bits not atoms' or in the assumption that, in cyberspace, different identities can be assumed that have no relation to the body or embodied self, or the fantasy, noted by Deborah Lupton, of ‘leaving the meat behind'. ‘The dream of cyberculture is to leave the "meat" behind and become distilled in a clean, pure, uncontaminated relationship with computer technology'.1 This can be seen in ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace', a document issued in 1996 by John Perry Barlow, one of the co-founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an organisation devoted to the protection of ‘digital rights'. In this document Barlow declares:

[O]ur identities have no bodies, so, unlike you, we cannot obtain order by physical coercion [...] In our world, whatever the human mind may create can be reproduced and distributed infinitely at no cost [...] Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here.'2

Such rhetoric is positively Gnostic in its disgust of matter. It also occludes the real bodies that make up the new, supposedly weightless, economy. Not just those bodies sitting in front of computer screens all over the developed and developing worlds, but the largely invisible, often exploited bodies that actually produce the goods upon which such an economy relies. This repudiation of the body also involves a disavowal of the sensory experiences of embodiment and, by extension, of aesthetics. Barlow's declarations and Lupton's observations may now seem old fashioned, and both date back nearly two decades, but the legacy of such thinking may well be the comparative lack of interest in aesthetics. However two recently published books engage with this much neglected question of aesthetics in the web and new media: Web Aesthetics: How Digital Media Affect Culture and Society by Vito Campanelli, and Interface Criticism: Aesthetics Beyond Buttons, edited by Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Bro Pold.

Campanelli's book is a bold attempt to go beyond the discussion of the web and digital media that is conducted largely in relation to questions of communication and dialogue, and to delineate a comprehensive understanding of such media and spaces in terms of their aesthetics. Campanelli builds up his argument carefully, starting with a critique of the idea of the web as a communicative space. In his first chapter, he is particularly exercised by what he describes as the monadic, autistic and monolingual aspects of the web which all seem to militate against its supposed dialogical and open character. In the next chapter, he presents an overview of aesthetics, taken largely from the work of Polish philosopher Wladyslaw Tatarkiewicz, as well as John Dewey and others, from which he proposes a concept of ‘diffuse aesthetics'.

In order to further develop this notion, Campanelli invokes the idea of the meme, taken from Richard Dawkins and developed by Susan Blackmore and others, which he connects in an interesting manner to the work of art historian Aby Warburg. Though acknowledging the importance of Warburg's famous library and the fascination of his curious ongoing arrangement of thousands of images, known as the Mnemosyne Atlas, Campanelli sees Warburg's concept of ‘engrams' - his name for the ‘expressive images that have survived in the heritage of Western cultural memory, and that re-emerge irregularly and disjointedly' - as a precursor of the idea of the meme. The third chapter engages in a useful discussion of the antinomy between the haptic and the optic in relation to new media, while the fourth chapter moves around, engaging with, inter alia, notions of movement and travel on the web, technological forms of memory, P2P networks and the practice of ‘camming', producing bootleg versions of films by videoing actual cinema performances. I found Campanelli's defence of this practice particularly intriguing, if not entirely convincing, especially the idea that the noise of the audience, necessarily captured in the process, becomes part of the narrative of this recording producing a new form of artefact.

Campanelli's final chapter is the point at which he shifts from the descriptive to the proscriptive, and offers concrete proposals for a ‘remix ethics' or ‘remix as compositional practice'. To make his argument he presents a useful history of remix practices going back to the dub reggae experimentation of 1960s Jamaica, through to the work of DJs in the '70s and '80s and on to Paul Miller (DJ Spooky) and Danger Mouse. The final section of this chapter, and of the book, is entitled ‘Machinic Subjectivity'. It starts with an interesting discussion of architect Greg Lynn's concept of the ‘blob', the term which he uses to refer to architectural projects which can take on different spatial configurations according to use. Campanelli extends this to describe the whole of society or at least contemporary architecture, media, arts and so on as blobs, inasmuch as they are ‘flowing, hybrid, malleable spaces'.

He uses the ‘blob' to argue for the dissolution of the distinction between the human and the machine, resulting in a dual or ‘machinic' subjectivity. From this he proposes the emergence of a ‘technological hyper-subject', which he discusses in relation to the ideas of the theorist Mario Costa, who has proposed a new understanding of art in relation to technology as flux. Campanelli relates this to various artworks by, among others, Eduardo Kac and Cornelia Sollfrank. Finally Campanelli finishes with Leonel Moura and Henrique Garcia Pereira's ‘Symbiotic Art Manifesto' from 2004, in which it is claimed, firstly, that machines can make art, secondly that man [sic] and machine can make ‘symbiotic art' and that this is a ‘new paradigm that opens an entire unexploited field in art'. Thus the claim is that we can abandon the hand-touch sensibility in art, or ideas of personal expression and the centrality of the human/artist (though this is of course a desire that has been present in art from the early 20th century onwards, evinced in the work of the Constructivists, Russian and otherwise, Duchamp, and onto postmodern and posthuman ideas about art and subjecthood). Finally ‘any moralistic or spiritual pretension and any purposive representation can be abandoned'.

Image: Moura and Pereira's Jackson Pollock-alike, 11.05.04, 10 mbots, 2004

Moura and Pereira have put these ideas into practice with their ArtSBot project, described by Campanelli, in which small robots, fitted with sensors and pens, move around a blank surface and produce marks that begin to resemble, for example, works by Jackson Pollock. At the point where a human subject involved in the process recognises the image is ‘just right' he or she stops the robots. Campanelli quotes from Moura and Pereira.

Although the robots are autonomous they depend on a symbiotic relationship with human partners. Not only in terms of starting and ending the procedure, but also and deeply in the fact that the final configuration of each painting is the result of a certain gestalt fired in the brain of the human viewer. Therefore what we can consider ‘art' here, is the result of multiple agents, some human, some artificial, immersed in a chaotic process where no one is in control and whose output is impossible to determine.

Campanelli describes this as the basis for a ‘brilliant manifesto for the art of the future [...] art as the result of both human and artificial actants'.

The problem is that this is a fairly weak vision of the future of art; robots more or less randomly scribbling, with a human deciding when the scribbles are ‘just right'. In particular it is hard to see what ethical or aesthetic force such work might offer. It does not even really go beyond a fairly traditional conception of human subjectivity as the rather disingenuous reference to ‘a certain gestalt fired in the brain of the human viewer' indicates. This is just a rather coy way of reintroducing the human subject and placing it at the centre of the aesthetic process once more. The capacity for humans to see something interesting in supposedly random patterns is at the very heart of humanism itself. Leonardo da Vinci famously ‘saw' landscapes in the stains on his studio wall.

I think if it is going to be possible to produce a relevant aesthetics for a digital culture it needs to be a lot more convincing and exciting than Campanelli's proposal. It should also be a lot more engaged with pressing political and social issues, such as the relation between new technologies and pollution or the exploitation of labour in the developing world, that are not really addressed at all in the final work described. Nevertheless, his book is an enjoyable and engaging attempt to think through the whole question of aesthetics in our particular set of hyper-technological conditions. As the above may indicate, I preferred the journey to the arrival at the final destination, not least because of allusions to thinkers whom I had not heard of hitherto, including, for example, the Polish philosopher Wladyslaw Tatarkiewicz, or the Italian philosopher of media and technology Mario Costa (though a quick google shows that, frustratingly, neither has been translated into English).

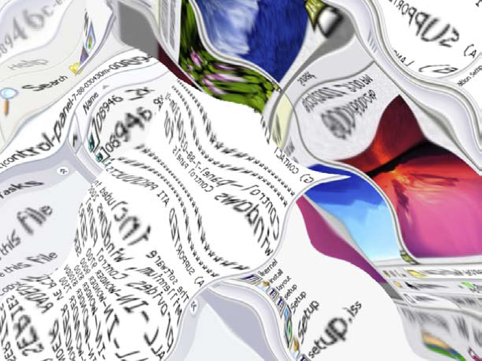

Interface Criticism: Aesthetics Beyond Buttons, edited by Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Bro Pold, and published by the Aarhus University Press, offers some extremely rich and interesting takes on the question of new media aesthetics. The book comes out of Aarhus University's Digital Aesthetics Research Center (DARC) and the Center for Digital Urban Living (DUL), and is a beautiful object, with excellent graphics, and even a cover image by net artist Alexei Shulgin. As its name suggests, Interface Criticism takes as its cue the notion of the interface, meaning not just the literal apparatus by which we interact with digital machines, but the more general interface between culture and technology. In the introduction Andersen and Pold posit the need to develop a critical vocabulary, and an ‘interface criticism', and to avoid the traps of either ‘transcending the interface' or ‘finding the core of the computer'. The collection aims to do this by broadening and generalising what might be meant by ‘interface' and by taking a far longer historical view than might at first be obvious.

To undertake these aims the editors have assembled an excellent collection of contributions, some by writers who will be familiar to Mute readers, others by less well-known ones. The first section looks at ‘Displays and History' and the first chapter, by Erkki Huhtamo, extends the notion of interface back to 19th century advertising and commercial publicity materials in the urban environment. In the next chapter, ‘The Haptic Interface: On Signal Transmissions and Events', Bodil Marie Stavning Thomsen looks back to 20th century art history, in this case the work of artists such as the Whitney Brothers, Peter Campus, Nam June Paik and Les Levine, as well as more recent art works, the hapticity of which anticipates current mainstream media practices.

The notion of hapticity is also present in Lone Koefoed Hansen's chapter, ‘The Interface at the Skin', which starts the next section, ‘Sensation and Perception'. In this chapter she looks at some of the tropes of immediacy and telepathy, which she examines in relation to experimental dresses designed by researchers at the electronics company Philips that include communications technology. Disconcertingly, the dresses look like they come from the 1960s, but are in fact only a few years old. The final chapter in the section, Søren Bro Pold's ‘Interface Perception: The Cybernetic Mentality and Its Critics; Ubermorgen.com', takes as its subject some of the cybernetically-informed work of the Ubermorgen new media collective, in particular their GWEI (Google will eat itself) and Psych/OS, a series of works about Ubermorgen founder Hans Bernhard's experience of mental illness and psychopharmaceuticals.

The section that follows, ‘Representation and Communication' features Florian Cramer's ‘What Is Interface Aesthetics, or What Could It Be (Not)?'. In this chapter Kramer studies the GUI in terms of transparency and the sublime of the concealed code, while Dragana Antic and Matthew Fuller's ‘The Computation of Space' look at the expansion of the idea of the interface beyond the classic GUI to encompass new devices and new spaces of interaction. In the next section, ‘Software and Code', both Geoff Cox in ‘Means-end of Software' and Morten Breinbjerg, in ‘Poesis of Human-Computer Interaction: Music, Materiality and Live Coding', take as their object of analysis ‘live coding', while Christian Ulrik Andersen looks at what he calls ‘Writerly Gaming: Political Gaming', taking Barthes' notion of the writerly text as his cue.

The last section, ‘Culture and Politics', extends the range of analysis to cover the expanded role and reach of the interface. Henrik Kaare Nielsen's ‘The Net Interface and the Public Sphere' revisits Habermas to look at how the Internet might become a public sphere and what might cause such a move problems. Jacob Lillemose's chapter ‘Is There Really Only One Word For It? The Question of Software Vocabularies in the Expanded Field of Interface Aesthetics' compares Windows Vista with Daniel Garcia Andujar's X-Devian Linux OS, and deconstructs the different discourses they operate within. In ‘Transparent World: Minoritarian Tactics in the Age of Transparency', Inke Arns looks at the work of a number of artists who are staging a return to older notions of transparency in interface culture. Finally, in a coda, artist Christophe Bruno looks at how the candidates in the last French presidential election seemed to mimic his ironic interventions in Google and other network spaces.

Image: Cover art for Interface Criticism by Alexei Shulgin

This is terrific book, with great essays which combine historical material with contemporary discussion. It manages to avoid both the Scylla of utopian hyperbole and the Charybdis of negative reactionary critique that still seem to characterise much of the discussion of new media. The chapters also strike an appropriate balance between technical know-how and theoretical acumen, with each informing the other in useful and effective ways. In passing it is interesting to note the references to the work of Jacques Rancière, who is becoming an important figure in the theoretical understanding of new media, as well of art and culture more generally. Though this collection is not ‘Rancièrian' in its intentions, it can be understood as a contribution to our understanding of the politics of aesthetics, particular as understood in Rancière's terms, as a ‘distribution of the sensible'. This is what Rancière calls ‘the system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions within it'.3 Rancière's focus on the sensible in relation to politics is a good counter-move against the angelic Gnosticism that still pervades understandings and discussions of new media. Above all it is a reminder that, unlike angels who have no bodies and thus no experience of the sensible, we are embodied and therefore our relation to the world is always sensible and aesthetic.

Charlie Gere <c.gere AT lancaster.ac.uk> is Reader in New Media Research at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Lancaster University

Info

Vito Campanelli, Web Aesthetics: How Digital Media Affect Culture and Society, Amsterdam: NAI Publishers, 2010

Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Bro Pold (eds), Interface Criticism: Aesthetics Beyond Buttons, Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2011

Footnotes

1 Deborah Lupton, ‘The Embodied Computer/User' in Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Embodiment, Mike Featherstone and Roger Burrows (eds.), London: Routledge, 1994, p.100.

2 John Perry Barlow, ‘A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace', 1996, https://projects.eff.org/~barlow/Declaration-Final.html

3 Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, London: Continuum, 2004, pg.12.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com