The New Labour: How to occupy a Factory

Tomas Zamot speaks to a coordinator of the worker-occupied and run Zanon tiling factory in Argentina the night before the state’s attempt to evict them

At the border with with Chile, 1200 kilometres South West of Buenos Aires, is Neuquen, home to some of the bitterest social struggles in Argentina. This is a beautiful part of the world, full of rivers, lakes and mountains, but also full of social contradictions. There is an oil well for every 20 people here, but half of the population lives under the poverty line. 20 percent are in a desperate situation.

The area’s oil, gas, refineries and oil wells are in the hands of Repsol, a Spanish company which is steadily poisoning local lands and rivers in the native Mapuche territories. Meanwhile, lands in the hands of foreign interests (Luciano Benneton owns 200,000 hectares; Ted Turner 50,000) remain well preserved. The situation of the owners of these enormous territories is quite different from the situation of the thousands that occupy pockets of land as places in which to subsist.

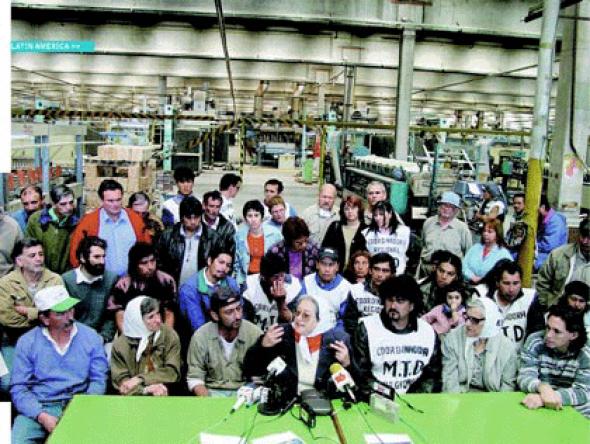

The ‘piquetero’ movement started in 1996 in the NeuquÈn town of Cutral-Co, following a massive loss of jobs after the privatisation of a local oil company. The popular uprising which consequently exploded saw successive confrontations between the army and the people, who had begun blockading roads to protest the losses. These same piqueteros were put to work again late in 2001, when the area’s ceramic factory, Zanon – the biggest in Latin America – came under the control of its 310 workers. These workers occupied Zanon when the owner announced his decision to close it and fire everybody, but during the occupation began to have problems with providing for themselves and their families. They made the decision to continue production whilst deciding everything together through workers’ assemblies. New union leaders distant from the old and corrupt administration were chosen, and work at the new Zanon began.

Carlos Saavedra is known as Manotas, or ‘Big Hands’. He is one of the coordinators of production at Zanon, chosen by the other workers because of his knowledge and experience. He has worked 10 years in the factory, and is 45 years old. Carlos is married with three children.

Tomas Zamot: What was it like working at Zanon before compared to working here today?

CS: It used to be like a jail working here. Before I started at Zanon I used to work in construction, which is tough work, but your boss doesn’t have so much control over you. Zanon was much tougher from that point of view. Now the situation has changed a lot. I really like working here now, even though I have to put in more hours because of my new responsibilities. You have to talk with your family and explain to them why you are working so hard!

TZ: How have you restructured the work process at Zanon?

CS: There are no hierarchies here. In the workers’ assemblies there is now total democracy. Three months ago, the assembly decided to choose coordinators of production, because until then we were not well organised. They choose me to be general coordinator; all the comrades voted for me. I’m proud, but it’s also a big obligation: I must work more hours.

We want people to be informed about how much we are spending, so we have meetings on Mondays and Wednesdays to exchange information with all the other coordinators, also elected by the workers. These coordinators always come with other workers, different ones each time, so that everyone knows what’s going on. We also make larger assemblies to keep all of the comrades informed.

TZ: How have these changes affected the process of production in your factory? CS: Production without bosses is very satisfying, a sensation that’s difficult to describe. Now we are proud of what we all make, proud of selling it and proud of making decisions for ourselves.

Without authoritarianism we are able to produce in a different way. For example, before we occupied Zanon, the owner wouldn’t allow people to drink mate [a coffee-like beverage]. That’s ridiculous, because we Argentinians drink mate all the time, but they wouldn’t allow it because they claimed it distracted workers from their duties. Now we are able to drink it, the workers are more creative: we’re even inventing new models for working.

TZ: How do you see Zanon’s changes in the broader context of Argentina?

CS: This factory’s workers are socialist, you might say. No one is ‘above’ anyone else. The coordinators and our union delegates are comrades: there are not the big differences that there once were. That’s the way it should be. We Argentinians have felt the oppressor’s foot on our heads for too long; we’re tired. Now we want to handle our problems by ourselves, and we don’t need people who only want to get richer and richer telling us what to do.

We want a state under the control of the workers to be in charge of the factory, with a plan for public works. We want to make ceramics for the hospitals and the schools. We want many more unemployed workers to be able to work with us. We can produce much more than we are producing right now. Only 10 percent of the potential of the factory is being used.

>> The Zanon Factory. By Sebastian Hacher

>> The Zanon Factory. By Sebastian Hacher

The spirit and creativity evident at Zanon have not only allowed production to continue but also increased efficiency and driven expansion. Since the workers took control here, a further 30 unemployed people have started work. People all over the country, employed and unemployed alike, now want to work somewhere like Zanon. Workers have reached very good levels of production, each earning 800 pesos, or almost US$270 a month, a very reasonable salary in today’s Argentina.

Nevertheless, the economic and political powers whose models have failed the Argentinian people insist on trying to destroy this experience. Tuesday 8 April saw an attempted eviction of Zanon’s new (self-) managers. The 310 workers remained within the factory the night before, a solidarity guard of hundreds standing watch. ‘I’m not afraid of the possible repression,’ Manotas said. ‘We know that the owner of the factory and the rich people from NeuquÈn and Argentina as a whole don’t want us here, self-organising in this way. They want the factory closed, with nobody using it. But this struggle has changed our lives for ever. Now we really appreciate our freedom. We want a country where we can work with dignity, without the humiliation of being cheated by bosses. It may be difficult, but we know now that we can make our own decisions, and we want to do it for as long as we can. We will fight till the end to defend production under workers’ control. We’ll give our lives for it. We won’t allow the police to enter the factory. We will continue producing and resisting, no matter how much they try to repress us. Our families know this and they support us. We are all in it together.’

>> The Zanon Factory. By Sebastian Hacher

>> The Zanon Factory. By Sebastian Hacher

Thankfully, Neuquen society has been givingg a lot of support to the workers. Zanon’s workers have excellent relations with unemployed workers’ movements, and the piqueteros vow to defend the factory as best they can against what Manotas calls ‘the ones who destroyed our country.’ Now, the Zanon worker says, ‘the only way is to fight for bread and dignity. If we need to strike or occupy our factories, we must do it, for our own good. There is no other way.’’

During the day of the evictions, over 4000 piqueteros, members of the left parties, human rights organisations, students, and workers in Neuquen and all over the country turned out to defend the dreams Manotas articulates. The receivers appointed by Judge Paez Chestnut came to take possession of the factory. In the event, the receivers appointed by Judge Paez Chestnut to take possession of the factory were kept at bay. Zanon's workers even felt confident enough over the levels of control they retained over the factory to allow the receivers in to take stock of the place. The overwhelming support and numbers made eviction an impossibility – this time, at least.

Tomas Zamot <tomas AT riseup.net> is an activist and reporter currently working in Argentina

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com