The New Art Etiquette

In the world of curating, Nicolas Bourriaud’s treatment of the notion of ‘relational aesthetics’ has long been making waves. Compared to the contemporary art galleries of Europe, the concept appears oddly under-represented in the English speaking world. The same applies for ‘New media art’ zones too. Here, Matthew Fuller reviews the book that might end all that

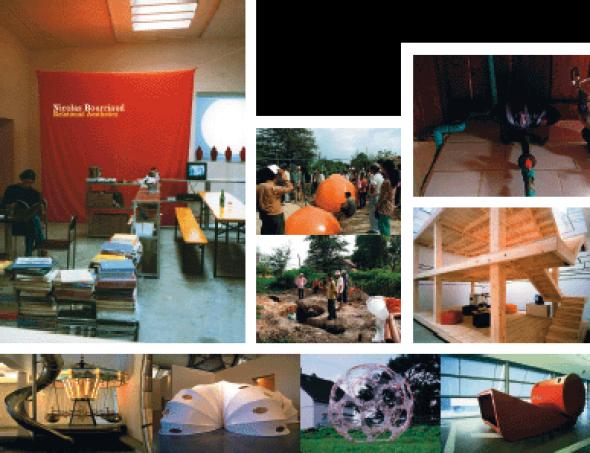

Relational Aesthetics is a short book of seven essays, mostly first out in Paris’s Documents sur l’art, on a strand of art that went on in the nineties. Bourriaud holds the office of director of the Palais de Tokyo, a contemporary arts space. An initial warning: some of the stuff championed is so goody-goody and self-regardingly humble you’ll likely wince blood. But beyond that, here’s the short version: art now is about relationships, not objects. Art has always been a set of social relationships mediated by objects, by images, but now it’s about relationships mediated by relationships. (That’s what you buy when you slap down the platinum on a Douglas Gordon it says here.)

More interesting is when the book gets down to detail. There’s a suggestive typology of the kinds of relational operations Bourriaud proposes in one chapter: but the listing of kinds of relations, amongst objects, ideas, acts, senses and people doesn’t remain static throughout. The ideas shift over time. Another thing that’s notable is the number of connections made between works, the list of artists dealt with. There’s not as many namechecks as a Hip Hop album but the writing, in this regard at least, takes itself on as a means by which to make its argument.

An advantage of books of essays is seeing the writing returning to squirm around key nodes of interest. One of these is the relation of art to activities which are apparently concerned less with perception and more with making something happen, something which is also ‘social’ and so on. Almost every essay briefly rephrases this problematic, but none – although they may be phrased like it – really delivers a final statement. That’s one thing that makes the book intriguing. But, in its constant circling around what in the end repels it, not so convincing.

In one essay Bourriaud calls for the creation of realisable utopian practices in the here and now. Subsequently, he taps out a reprimand to any explicit function of politics in art. Instead, the proposal is to produce conditions in which the capacity of art to think about itself thinking opens up an experimental chamber of particular relational acts. These are not to have demands of use put upon them, nor to go much beyond knowing prototypes. A chapter devoted to Felix Gonzalez-Torres is perhaps where he makes his case best. At the same time, the book would do well to recognise its own situatedness within art. Art, like anything else, suffers when it is simply instrumentalised by business, social work, or, and this is something missed here, by art systems.

There is a general blind spot towards those processes that do not come correct with artist and gallerist, or towards activities that have taken art methodologies and moved them outside of the circuits. At the same time, within this schema Bourriaud is worth reading for the lists of artists, processes and shows that worked with a complex set of relations and for how the various ways this set of concerns inflect and refigure – however over-carefully they might be managed – ‘relationships to the world.’

One theme of the book is how the implications and effects of media and technologies of communication are, in art, often taken up in other media. The impact of photography on painting is well known. Relational work can be seen as a transduction of the effects and dynamics of computer networks into other areas. By such means, Bourriaud argues, artists are freed from the slow confrontation with technique or from technology’s various cultures of use. I suggest there are reasons to think art strong enough to cope with such contamination, and that Bourriaud’s argument is essentially conservative here. It’s just sloppy for instance to suggest that, ‘Henceforth the group is pitted against the mass, neighbourliness against propaganda, low-tech against high-tech, and the tactile against the visual.’ Nevertheless, the key point is well made, and it would be worth addressing to the equally limited scope of ‘electronic’ or ‘media’ art. Relational Aesthetics is clear enough about the relational potentials embedded in and created by means of objects, it doesn’t fall for repeating the dematerialisation schtick, nor for getting fixed on objects, so this avoidance of a particular kind of materiality sits oddly.

The theme of relationships mediated by relationships obviously links to other debates going on, in politics, economics and elsewhere. Some of these are mentioned here, via Althusser, Deleuze, Debord, but they’re never really dug into. To do so, to suggest that the ‘staging of devices of existence including working methods and ways of being’ is possible in a reflexive and experimental manner in other areas, would too easily disrupt the special case that Bourriaud makes for art. This can be sensed – and the writing is sharp enough to partially map its own discomfort in its own limits – in the last text’s engagement with the aesthetic ideas of Fèlix Guattari. Others would argue that, art or not, it is of fundamental importance that such experiments are made in and between all such areas. This book starts to trace the ways in which some of the currents in art are continuing to stage such relations. It does show signs however of the need to get out of the office a bit more.

Relational Aesthetics // Nicolas Bourriaud // Les Presses de RÈel // Trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods with Mathieu Copeland // Paris, 2002 // A5, 126pages

Palais de Tokyo [http://www.palaisdetokyo.com]

Matthew Fuller <fuller AT xs4all.nl> works at the Piet Zwart Institute Rotterdam [http://zwart.wdka.hro.nl]. He is the author of the forthcoming Behind the Blip, essays in the culture of software, Autonomedia.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com