Museum Epidemiology

Betti Marenko visits London’s latest art & science highlights, CleanRooms at the Natural History Museum and Ansuman Biswas at the Whitechapel, and considers the possibilities for art to subvert techniques of science without being contaminated by them.

The subtitle of CleanRooms, a collective show at the Natural History Museum, is telling: ‘art meets biotechnology’. The exhibiting artists Neal White, Gina Czarnecki and Brandon Ballengee, plus a performance art piece by Critical Art Ensemble that launched the exhibition (not reviewed here: see http://critical-art.net), engage with the notion of the ‘clean room’, the highly controlled, sterile and sinister (sic) environment of scientific laboratories. Clean rooms operate by minimising possible factors of contamination (i.e. the human). This striving is underpinned by the rational presumption that equates science with the isolation of the object of research. Indeed to eliminate pollution, which is effectively to ignore or dispose of the very network which allows any object or event to exist, is the core around which western science is structured. To this deity of science the hazards generated by the heterogeneous and the heteroclite are happily sacrificed.

This is clearly articulated by Neal White who has recreated a monstrously mutated laboratory, a very un-clean room where things are going contagiously wrong. If the aseptic laboratory regime commands whoever enters to wear the bunny suit to prevent the environment’s adulteration, in White’s freakish lab a vengeful role reversal has taken place. The human body, contamination par excellence, morphs into a even greater pollutant (the felt covered figure), is expelled by both the clean room and the artwork (the artist-less Victorian drawing machine) or ends up being devoured (the bunny side half swallowed by the bubble).

This is clearly articulated by Neal White who has recreated a monstrously mutated laboratory, a very un-clean room where things are going contagiously wrong. If the aseptic laboratory regime commands whoever enters to wear the bunny suit to prevent the environment’s adulteration, in White’s freakish lab a vengeful role reversal has taken place. The human body, contamination par excellence, morphs into a even greater pollutant (the felt covered figure), is expelled by both the clean room and the artwork (the artist-less Victorian drawing machine) or ends up being devoured (the bunny side half swallowed by the bubble).

CleanRooms draws a comparison between the clean rooms of scientific research and the white space/white cube that has signified the ethos of exhibition ad nauseam. A regime which then spills into design conscious spaces (bars, restaurants, shops). Here, the white cube aesthetic helps turn the customer into the purchaser of various experiences of consumption. Common to both is the desire to isolate the object of observation. In order for such arbitrary manoeuvring of purity enforcement to function, however, interconnectivity among bodies must be ignored. The implications are well known: when discrete segments come to delimit a portion in a continuum of intensities, when the absolute signifier rises from the flux, assimilating all concatenations, it is the triumph of the Good, the Beautiful, Science, Capital. An operation only made possible through technologies of homogenisation that level any aberrant data to the equivalent machine of botoxification. What is disposed of as the contaminating human factor is the entire pathosphere of the living/loving, without which we could not even begin to grasp the slice of matter and affects we are made of.

In the past Ansuman Biswas has questioned western conceptions of science right up to the hiatus of object/subject and its fundamental implications for the legitimisation of scientific objectivity. He once spent ten days meditating, locked in complete isolation in a black box, using the Vipassana technique not just to promote a rhetorical comparison between eastern and western belief systems but rather to break the subject at the core of its definition and to reintroduce awareness as a tool against the extreme fetishisation of knowledge. Western science – one-dimensional, profit-driven, enslaved to neoliberalism and blatantly neglectful of life-affirming interconnectivity – has a lot to learn from eastern philosophies. In particular the knowledge concerning cultivation of awareness and stillness. These body-based technologies must be employed, in relation to science and not only to grasp the invisible threads between bodies, but to see the space in between things.

In the past Ansuman Biswas has questioned western conceptions of science right up to the hiatus of object/subject and its fundamental implications for the legitimisation of scientific objectivity. He once spent ten days meditating, locked in complete isolation in a black box, using the Vipassana technique not just to promote a rhetorical comparison between eastern and western belief systems but rather to break the subject at the core of its definition and to reintroduce awareness as a tool against the extreme fetishisation of knowledge. Western science – one-dimensional, profit-driven, enslaved to neoliberalism and blatantly neglectful of life-affirming interconnectivity – has a lot to learn from eastern philosophies. In particular the knowledge concerning cultivation of awareness and stillness. These body-based technologies must be employed, in relation to science and not only to grasp the invisible threads between bodies, but to see the space in between things.

These themes have returned in Biswas’ recent work on show at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. Part of his installation is a video whose protagonist is an odd figure in a white coat wearing a zebra’s head – a cheeky mutant unleashed into the lab. What may seem yet another hybrid pollutant reveals itself to be a commentary on the Kafka-esque fate of the zebra fish (of Indian origin like Biswas himself). The zebra fish was saved from extinction only to be placed into slavery in scientific labs world-wide because of its very useful epidermal property. Because the zebra fish stripes (hence the name) are transparent they allow scientists to observe in detail what happens within the fish organism, for instance the effects of genetic processing. This is every scientist’s dream: a body whose skin lets the gaze in, where cause and effect are colour-coded and perfectly traceable and where the modern anatomist knows exactly where to cut. The fantasy of seeing the invisible becomes reality. The eyes are probes. The drive is to dissection.

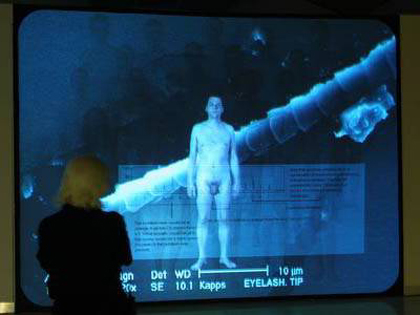

The other Biswas’ work, Still Life, is a digitally rendered visualisation of several scientists’ cheek samples. On the screen in real time, this is a simulation of a glottolalia whose main referents (the babelic, self-involved, hierarchical discourse of science, its rigidly structured modalities of truth/falsehood, etc) die in a sea of pixels whose bright ever-changing, colours cannot distract the viewer from the fact that s/he is watching a representation of the invisible. The prosthetic eye of microscope-cum-digital-camera captures the movements of bacteria at a molecular level and shows the minimal unit of segmentation of living matter. Probe. Reduce. Ex-terminate. Scientific scopophilia turned into art? Or art turned prey of the pornographic gaze? Could it be that the mythologies of science – new horizons to explore, new possibilities to seize, new territories to colonise – are much closer than expected to the pornographer’s drive toward the black hole?

The issues raised go well beyond the artworks in themselves to broach the modes of production of any meeting between art and biotech. Specifically, they concern the seldom questioned and rarely criticised use of technoscientific devices of production and representation. Thus, video technology, deployed in its fully hyperscoping function, i.e. by linking it to a microscope for a digital rendering of the invisible, is ubiquitously creating the idle experience of yet another screen-watching moment. Example of this tendency are everywhere. Apart from Biswas’ above, Czarnecki’s work, in CleanRooms, is another one. Silver Altar shows 22 subjects on a giant screen and, thanks to a conspicuous apparatus of interactive technology, it involves the audience in a preposterous genes selection exercise, enveloped by a background data-noise captured from samples of the bodily fluids and internal organs of the humans who took part.

>> Image from Silvers Alter, Gina Czarnecki. Camera: Roland Denning

>> Image from Silvers Alter, Gina Czarnecki. Camera: Roland Denning

Thus, the issue concerns how to rely on scientific signposts (the petri-dish, the microscope, the clean room, digital high-tech) and standard lab procedures in art practice. If the dialogue between art and science is only too obvious, what remains to be discussed is the extent to which scientific procedures are seeping in and moulding artwork through their powerful discourses and seductive icons. What must be asked is why technoscience is rarely dealt with experimentally and why its modes go un-discussed, pre-emptying art from having political relevance. The artistic deployment and aesthetisation of normal laboratory procedures risks constantly being recuperated by the corporate state. Can the mere act of site swapping – from the labs to the gallery – induce a shift in the signification of standard operations?

The use of standard lab practice in art replicates the rhetorics of pro/contra that afflicts the biotech debate. This self-reinforcing, ultimately misleading dilemma deploys moral questions whose resistance to resolution is indeed very appreciated by the corporate state and which diverts critique away from processes of production and consumption of biotech. As Critical Art Ensemble have emphasised, this issue concerns people’s access to biotech knowledge, at least enough to enable them to exercise some power/control. At present the western world and the US in particular, ‘a giant petri dish’ says Ballengee, is an experiment that can afford to neglect popular opinion thanks to the muddled access to knowledge.

>> From Farm to Pharm, Brandon Ballengée

>> From Farm to Pharm, Brandon Ballengée

Paradoxically, the less high-tech piece, Brandon Ballengee’s From Farm to Pharm, an open-contribution collection of images (ongoing: submit to farm2pharm AT nhm.ac.uk) that charts the evolution of artificial selection, ends up being the most effective, having the straightforwardness of a school assignment, the grassroots quality of an open project and a captivating network of curiosities à la Colors. The contiguity of the images (both on the wall and online) creates a pictorial history of ‘sculpting with living tissue’. Also, it shows how the by-products of a controlled breeding and domestication of ancient species like humans differ from biotech production, whose long-term effects are still unknown and only speculative. A rose is a monster of breeding techniques, says Ballengee, but the register it belongs to is radically distinct from, say, the fish farmer who chooses the ‘best looking’ shade of pink (thanks to the SalmoFan range) or the Flavour Saviour fish genes implanted in tomatoes for antifreezing purposes. On one hand there are evolution’s random choices that operate, in long time spans with individual experiments repeated millions of times with negligible risk of dangerous genetic solution (that’s why life on Earth is still flourishing). On the other hand, there are biotech products, pressured by the market and in disregard of scale, space and time. Again it’s a matter of velocities.

The question is open: How is a molecular revolution brought about within the molecular invasion Critical Art Ensemble talk about? How is superfluity, beauty, risk and desire brought into an art that dissimulates laboratories’ means of production under the patronage of research institutions? What must be questioned is the role of biotech as a resource for a new aesthetics, one which does not fill the void left by body art but acts as its necessary development. This awareness calls forth the capacity of art practice to interrogate and resist the nexus of power formations, cultural representation and material apparata within which it finds expression. In fact, any intersection of art, living entities and technoscience must engage with the modes according to which surfaces are hijacked by capital; creative flows are placed under control by agglutination; experimental and autopoietic instances of subjectification are managed; guidelines are issued and, yes, genes are patented. In this way transversal dissent, molecular cross-pollination, tactical practices of sudden variation of speed are free to excavate spaces of manoeuvre and maintain un-reducible to the generalised equivalence of capital. Luckily, no clean room can stay immune from destabilising dirt for too long.

CleanRooms, the Natural History Museum, 20 June – 3 August,

Ansuman Biswas and Emily Wardill’s work is currently on show at the National Institute of Medical Research, until the end of September.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com