Multi-Dimensional Man

Restlessly experimental, artist, writer and Burroughs collaborator Brion Gysin didn't stop to consolidate his oeuvre. But with a dedicated publication and New Museum show, his aesthetic nomadism is finally being brought in from the cold. Review by Mark Jackson

Brion Gysin: Dream Machine surveys the work of the multi-disciplinary artist Brion Gysin (1916-1986) not only in its historical context, but also in terms of how we might consider its contribution to contemporary practices.

As a document it positions itself as being of interest to both those attracted to Gysin's association with the Beats, and those who may be looking for a more historical substantiation of his artwork. It paints Gysin as an outsider artist; a frustrated figure in need of recognition and achievement, but equally hampered by his own diversity of practice.

Despite the conspicuous stillness and silence of the printed page, Brion Gysin: Dream Machine - part biography, part catalogue and part critical work - is as heterogeneous a survey as Gysin requires. He is certainly not an easy subject for overview, since he refused to remain in one place, moving through practices and lines of enquiry with intelligence and precocious ease. For an English-born Canadian, expatriated to Paris at the age of 18 in search of art, it is difficult to determine whether he is drifting or seeking out the very places in which he finds himself. Accounts of his life come across like a series of scenes, both in the theatrical and social and cultural senses. Perhaps fittingly, Brion Gysin: Dream Machine is a book of parts. It does not flow, but jumps and skips. Essays on Gysin and his work are interspersed with photographs, stills of performances and facsimiles of paintings, poetry and the pages of books, finishing, with a do-it-yourself Dream Machine.

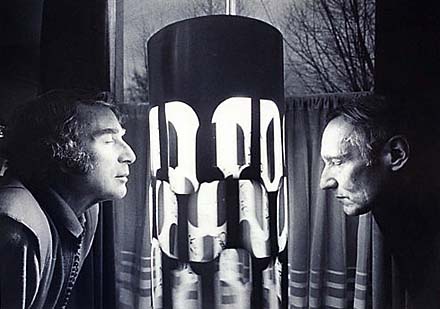

Image: Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs by the Dream Machine

The first essay by Gysin's biographer John Geiger opens with a quote by Gysin describing himself as having been born in the ‘wrong time, wrong place, and wrong colour.' This is, perhaps, the central paradox of the man and his work. For Gysin is the essence of an artist whose trials and apparent failures, and ceaseless transformations are those which make him so important to contemporary audiences. Gysin was haunted by the sense that he had missed a trick, that he had covered too much ground, particularly in his shifting back and forth between writing and painting. He felt that if he'd stuck to one discipline, then he would have achieved the fame and financial security he sought. Yet it is precisely where these shifts occur and where the disciplines meet that his work becomes most powerful, and his resonance in and importance to contemporary practice begins to become clear.

Like a previous survey of his work, Jose Ferez Kuri's Brion Gysin: Tuning into the Multimedia Age, Brion Gysin: Dream Machine is published in association with a retrospective exhibition of his work. The 1998 retrospective at the Edmonton Art Gallery - now the Art Gallery of Alberta - and the 2010 exhibition at the New Museum.

The New Museum, New York, has a mission: ‘New Art, New Ideas'. Yet with this apparent exemplification of the New, they have scheduled a retrospective exhibition of an artist who died in 1986. The location of the New Museum is unmistakable for admirers of Gysin's friend and collaborator William S. Burroughs. It lies on the opposite side of the Bowery from ‘the Bunker', the partially converted YMCA and his New York home in the 1970s. Gysin had stayed in New York in his late 20s and early 30s, working as a costume designer. Barry Miles, in The Beat Hotel, quotes Gysin as saying of his time there, ‘I was always on the wrong side of the street [...] just exactly opposite.' Gysin's work is far from being universally accepted as an important contribution to 20th century art, whilst Burroughs is regarded by many as one of its most important writers. However, now at the New Museum it appears Gysin may have finally crossed over into acceptance.

Both the exhibition and the book posit the idea that Gysin's work be considered relevant to the New, in having importance for contemporary artists. Part of the allure of Gysin is sustained through those who make claims of his influence and importance, not least Burroughs himself, through whom many come to hear of him.

On the surface Brion Gysin could be easily dismissed as an adjunct to the cultural movements of the last century, particularly his oft mentioned association with the Beats and the Surrealists. He might appear as an individual whose ideas and explorations had an undeniable impact on William Burroughs, yet whose own achievements are perceived as peripheral to the developments of western culture.

His influence on Burroughs is undeniable; the most prominent examples include his introduction of Burroughs to the mathematics graduate Ian Sommerville, who would later work with Burroughs on another of Gysin's groundbreaking experiments with sound. We can also see the significance of Gysin's influence through his introduction of Burroughs to L. Ron Hubbard's Dianetics, which came to significantly influence the Burroughs' theories around technology. The major influence, however, is Gysin's invention of the Cut Up technique, which was to become so crucial to the development of Burroughs' work. As this particular influence so aptly demonstrates Gysin's propensity to apply ideas back and forth across artistic disciplines it is worth summarising here.

Burroughs would frequently recount how in 1959, the same year that Olympia Press published his ground breaking Naked Lunch, Gysin explained to him that writing was 50 years behind painting. The most significant example of this being the Cut Up technique, which both men saw as a text-based and narrative-based development of the pictorial collages of the Cubists. Gysin had been preparing a mount for a drawing, cutting through card resting on a number of newspapers. Having lifted away the mount he discovered the fragments of newspapers and advertisements, layered and realigned, revealing amusing phrases. At the time Burroughs was in London undertaking an unconventional cure for opiate addiction. Gysin, however, saw that such techniques were an amusing example of his urging Burroughs to adapt techniques of painting to the written word, and on Burroughs' return presented his discovery.

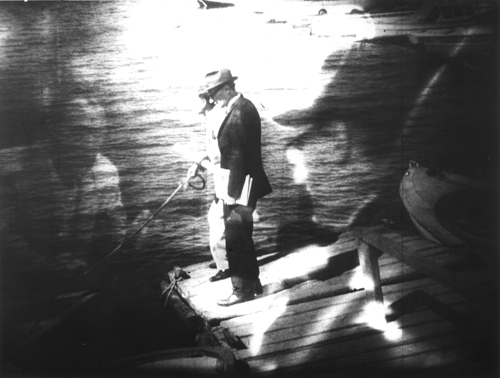

Image: still from Antony Blach's The Cut Ups, 1966

Burroughs thought Gysin's results to be not just amusing, but also a more accurate representation of ‘the facts of perception' and prescient to the degree that they could be used to manipulate reality. He went on to explore the physical cutting and splicing of the collage, but with the written word, slicing through pages to create new meanings from old text. Burroughs was to take the Cut Up to extremes in a series of hugely influential books, essays, film collaborations (with British director Anthony Balch) and tape experiments, some of which also involved collaborations with Gysin.

Brion Gysin: Dream Machine doesn't deny Burroughs' prominence in Gysin's career. His name and image appear as a refrain throughout the book, and it may appear almost perverse to see the inclusion of an essay entitled ‘On Burroughs's Art' as though there wasn't enough to say about Gysin's. However the more one looks, the more one sees in Gysin's output a breadth and rigour of engagement with culture distinct from his work with Burroughs, which also offers a sensorial counterpoint to Burroughs' wild, satirical polemic. The principal achievement of this book, and accompanying exhibition, is to demonstrate the importance of Gysin's work both with and without Burroughs on equal and inextricable terms.

Gysin's own cross disciplinary activities with words and images were both visually less brutal and less visceral than Burroughs'. Many of his canvases are constructed in a manner adopted from the top-to-bottom reading of Japanese calligraphic script, and right-to-left of Arabic, whether painted by hand or via specially adapted rollers. The process was not shrouded in secrecy - footage of their making can be seen in the Anthony Balch and Burroughs collaboration film The Cut Ups. Likewise in 1960, at London's Institute for Contemporary Arts, Gysin painted a picture as performance while a tape machine played a cut up, working with the words: ‘You in the Word and the Word in You is a word-lock like the combination of a vault or a valise.'

Image: An example of Brion Gysin's calligraphic style from his time in Tangiers, 1950

This evidence of process is an important part of Gysin's practice; his explicitly titled novel, The Process, was purported by Gysin to engage itself with the process of reading. At a screening of a documentary on Burroughs I attended I asked one of his biographers, Barry Miles, a question regarding the status of his experiments with sound. Miles replied by saying that Burroughs saw them, just as his paintings, as a ‘means of investigation'. My own interest in both Burroughs and Gysin has taken me back repeatedly to this phrase, and at its heart this book stands as both an investigation of Gysin, and a demonstration of how his work epitomises investigation - both in its making and, essentially, in how we engage with it as audiences.

Laura Hoptman's essay - ‘Disappearing Act: The Art of Brion Gysin' - at the book's centre, instantly recognises what is, for me, Gysin's true brilliance and resonance in contemporary practice. She swiftly announces his interdisciplinary ‘in the extreme' practice, and very subtly introduces us to the synthesis inherent in Gysin's practice, between, on the one hand natural chaos and chance, and on the other machinery and the permutations of the computer.

Just as the ‘Beat Generation' is a convenient, and hugely problematic, categorisation, so Gysin's work defies the convenient summary of a monograph. Hoptman's inclusion, however, is a summary that matches up to Gysin's work in as much as it suggests potentials and investigations, with the knowledge that the encapsulation of Gysin's process is ultimately unachievable.

Gysin's brief dalliance with André Breton and the Surrealists is recounted as an important early moment in the life of the young painter, particularly in the case of Gérard Audinet's convincingly bitchy representation of both Gysin and the scene in his essay ‘The Wounded Man: Brion Gysin, Unhung Surrealist'. It is interesting to note, however, that the earliest reproduction of a work by Gysin is dated 1941, six years after he was callously removed, under Breton's direction, on the eve of the opening of what was to be his first exhibition. His, almost Rimbaudian precociousness as a young artist, 19 at the time of the exhibition, is lost from this compilation other than in the form of anecdotes.

Likewise, on my first glance through Brion Gysin: Dream Machine, I was immediately struck by an incongruity between one of his major pieces of work and its representation in this book. The work in question is his late painting Calligraffiti of Fire, a vast multi panel painting I saw at the October Gallery in early 2009. Here, to accommodate its length, nearly 60 feet, it has been scaled down across two pages, a letterbox view of a behemoth. This challenge to, what was for Gysin such a major piece of work, is symptomatic of any attempt to accurately represent his work in its scope and detail.

Gysin's projects are best served in the flesh. Dream Machine paves the way for reassessment and acknowledgement of Gysin's achievements with a multi-faceted, if very occasionally repetitive, view into Gysin's tortuous attempts to achieve greatness in the various fields he put his mind to.

Gysin himself believed that his work had not achieved the respect it deserved because of the many different activities he put his hand to. Yet it is this multidisciplinary approach that stands out as one of his most valuable qualities with respect to his relevance for contemporary art. This book deals with his paintings, collages, light machines (the eponymous Dream Machines), concrete poetry and, briefly, his multimedia performances.

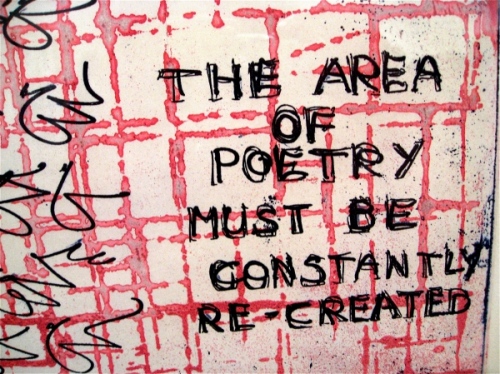

Image: I Give You You Give Me, May 28, 1965

Dream Machines also provides a vital starting point for the indisputable resonance of Gysin's work in contemporary multidisciplinary practice with contributions from as diverse a group of artists as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Genesis P-Orridge and Cerith Wyn Evans. Their various contributions demonstrate the cross-media resonance of Gysin's practice, but they also underline one of the most vital aspects of addressing Gysin, or Gysin and Burroughs', practices. This is their advocacy of new investigations, of taking their experiments further with regard to our own engagements with the world. We are implored by Burroughs and Gysin's most significant collaborative thesis, The Third Mind, to try the Cut Up experiments for ourselves.

The addition of works by artists reacting to Gysin's work also acts as a potential summoning of the concept from which The Third Mind gets its name. The title was drawn, according to Gysin and Burroughs, from Napoleon Hill's 1960 self-help bestseller Think and Grow Rich. It expressed the idea of a third, superior mind, arising out of collaboration. The rather unsettling superimposed photograph of a Gysin-Burroughs hybrid near the book's opening, and the inclusion of a piece by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, who went on to exemplify the combined image from a surgical perspective, are not the only collaborative forces at work here. In fact it is through the comparison of the various parts that the superior concept emerges. Gysin might have felt hampered by moving through various disciplines, but it is their interaction that fits so closely with the activities of artists in the 21st century.

Our own direct collaboration is ultimately encouraged by the inclusion of the do-it-yourself Dream Machine. Gysin's principle achievement for me is his emphasis on the validity of subjective interaction with art. This is outlined in his assault on western language within his paintings and concrete poetry, but activated most successfully in his Dream Machine, a device that that defies an interpretation other than the subjective experience of the viewer's interaction with the technology. The machine rightly opens this book in its title, and closes it with the reproduction of the do-it-yourself version published in Olympia magazine.

Image: Brion Gysin, The Area of Poetry Must Be Constantly Re-Created

The Dream Machine is a stroboscopic device built to encourage hallucinations amongst its users. One would sit in front of it with closed eyes, where the pulsing flashes of light would stimulate the optic nerves. In an accompaniment to the design, Gysin writes, ‘The Dream Machine may bring about a chance of consciousness inasmuch as it throws back the limits of visible world and may, indeed, prove that there are no limits.'

Brion Gysin: Dream Machine demonstrates the limitation of both Gysin's work and its reproduction. However, whilst doing so it provides a highly effective introduction to a practice that attempts to break the limitations of expression and release artefacts that are alive in their demands for active engagement.

Gysin's work highlights the necessity to actively engage with art as a means of investigation. His work yearns for the ongoing, penetrating evisceration already undertaken on William Burroughs. I am hopeful that Dream Machine will promote such a potential engagement by demonstrating the continued relevance of Gysin to contemporary practitioners.

The means are our machines [...] machines in the hands of anybody can push a button. Take your own tape recorder [...] Record your very own voice on a length of tape. Better read something you consider important.

- Brion Gysin, Let the Mice In

Mark Jackson <mark AT imagemusictext.com> is the curator at IMT Gallery, London. He is currently conducting his PhD research at London College of Communication on the relationship of William S. Burroughs to audial arts.

Info

Laura Hoptman, Brion Gysin: Dream Machine, Merrell Publishers Ltd, 2010

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com