In the Mud and Blood of Networks: An Interview with Graham Harwood

'Double Negative Feedback' expresses the hope that the chaos unleashed by the cybernetic loops

Graham Harwood and Matsuko Yokokoji (YoHA) build contraptions that expose and collapse down the productive chains linking telecommunications media to some of the raw materials that constitute them. In this interview with Anthony Iles however, Harwood rejects theoretical discourses of resistance in favour of a more direct and technical method of ‘action research' which skirts art and politics

In the 1990s Graham Harwood's work with the media arts and education group Mongrel plotted a characteristically antagonistic approach to cultural hybridity and the social uses of technology. Since the scattering of the group's original members (Richard-Pierre-Davis, Mervin Jarman, Graham Harwood and Matsuko Yokokoji), Harwood's collaboration with Yokokoji, as YoHa, has produced, among other projects, a series of works which examine the material qualities, histories and applications of industrial materials, namely coal, aluminium and tantalum. Each of these materials has particular relevance to the manufacture of computing and telecommunications technologies. Investigating their materiality provides multiple lines of flight from the mystifications excused by terms such as ‘immaterial economy' or ‘immaterial production'. These terms encourage contemporary production's camouflaging of labouring and suffering bodies. Attention to only the ‘immaterial' falls short of showing how capitalism puts materials, machines and bodies to work to produce value. YoHa work with the media that each of these particular materials create, and treat the materials themselves as media which simultaneously condition human bodies and communicate human conditions. Each project forms collaborations with individuals and groups whose lives are intertwined with these materials at the level of extraction and industrial application, and the social networks supported by the communications technologies they drive. While the materials are deployed in machines which are made to recursively research themselves and their effects, they also inscribe records of the bodies they decimate.

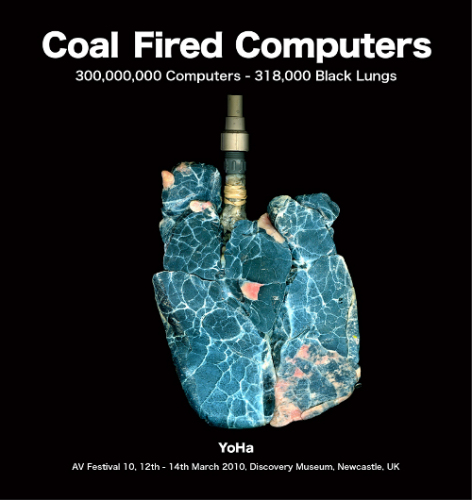

One of most celebrated of these projects was initiated this year at Newcastle's AV Festival. The project, Coal-Fired Computers involved powering computers directly with coal via a steam-engine. As the computers crawled the internet searching for data on coal-related deaths, a pig's lung inhales and exhales exhaust fumes from the coal combustion visually registering the extent of pollution and decay induced in living matter through coal's use as a source of energy. The project involved extensive research carried out by Jean Demars into the coal-mining industry in the UK and engaged mining communities and former activists. Rather than a simple catharsis, as in Jeremy Deller's work on the miners' strike in which history's losers get to play the victors, Coal-Fired Computers opens historical wounds to the salt of contemporary world production. Jean Demars, speaks of the difficulty of approaching people ‘to participate in a project where sick flesh is resuscitated by what killed it in the first place, and speak up on what they lost and never quite recovered from.'i

In a talk given at the AV festival, ex-miner and NUM activist, Dave Douglass, drew direct connections between the closing of the UK's coal mines, statistics about UK miners' compensation claims for health damage and the conditions of ‘invisible' workers producing the six billion tonnes of coal imported yearly by the UK from China and India.iiThe shift in the UK, under Harold Wilson, to an economy oriented towards ‘the white heat of technology' can be understood as a shift not from dirty technology (coal) to a clean one (nuclear) but rather a displacement of the burden of labour used up to produce this fuel on to distant, less visible and less recalcitrant bodies. The UK presently imports the same amount of coal it used to produce domestically in the 1960s. This imported coal powers the computer and communications technologies which support the UK's service sector. In the 1980s miners' compensation claims enriched legal and insurance companies which contribute significantly to this service based economy. Even after the closure of the mines, miners' bodies were put to work as the bedrock of the ‘new' economy, whilst in China and India workers produce the raw fuel and the microchips essential to the UK's finance, insurance and real estate sectors.

Throughout our interview Harwood uses the term ‘contraption' to describe the works discussed. The term is fitting, in that YoHa's projects involve the building of machines, or assemblages, which only barely ‘work'. Rather than smoothly functioning, these assemblages motion towards a demystification of technological apparatuses. They produce allegories in the place of utilities and these allegories in turn output images which infect and taint historical representations.

For the book Aluminium: Beauty, Incorruptibility, Lightness and Abundance, the Metal of the Future, YoHa used a number of promotional films for the aluminum industry keen on promoting its use. These films were used as source material from which to generate a series of images which break down the framing and editing of their sources. ‘Because we despise the precise, mechanical, glacial reproduction of reality in these films, and as we are not interested in the movement which has already been broken up and analysed by the lense, we code up ways for time to occur across the division of the frame.'iii A string of code associates, search terms and internet search engine results with each film frame and re-renders the film to predict movement between frames and sometimes between the previous editors' cuts. The effect produces a mesmerising liquid sequence of images in which the separation between frames and therefore between activities - consuming and producing - and materials is collapsed, merged into a startling alchemy of humans, foodstuffs, information, machines and materials. It is as if the regular division of time of the old film stock has been exposed to the illumination of continuous duration and convergence of matter it had sought to hide.

A critical understanding of technology is central to a transformative understanding of the means and relations of production which make our world. Do particular technologies produce particular social formations, or do particular social formations need particular technologies?iv Furthermore, if we can answer either of these questions in the affirmative, then how exactly are we integrated into capitalist technologies and how are they integrated into us? Often left perspectives fall into two basic camps - those who believe the means of production are basically neutral but just in the wrong hands and those who believe that technology is inherently oppressive. These works and the interview which follows hazard the argument that artistic means can show us something about these relations that critical theory or the critique of political economy cannot. As Harwood notes, YoHa's work moves between any number of artistic strategies to achieve its ends. My own thinking privileges some of these above others. If there is a weakness in the practice at all then I think it is where the work sometimes softens its charge by being too easily read as simply participatory or ‘relational'. Like an edu-science diorama, Coal-Fired Computing is persuasive and invites curiosity, it runs the risk of being perceived as superficial illustration of the elements and themes it compounds.

Therefore, it is important that its complex intertwining of the human and material be followed beyond its immediate support and into the networks it moves through. What appears as most aesthetic is, on the contrary, material and what appears most materialist should be conceived on aesthetic terms. Therefore, what appears as given, natural, should be made strange and alien. What appears unchanging should be seen as transitory and pregnant with potential change. It is crucial that such meaningful work forces a slide in these categories that would otherwise be crudely brought to bear upon it. YoHa and Harwood's work does just that, feeding pre-existing theoretical categories into their contraptions along with all the raw materials, tools and human labour power. It is a grizzly process that mirrors the application of technology to the satisfaction of needs determined by domination. However, in diverting its operations towards novel outputs, so begins the work of excavating from this mess its opposite. If we are not yet ready to ask ‘what might an emancipatory technology look like?', it is because the instruments currently shaping the terms of the question must first be turned into their own criticism.

Anthony Iles: These three projects, Coal Fired Computers, Aluminium and Tantalum Memorial deal with a social history and social present of material. Was it a conscious move to specifically approach issues - like globalisation, exploitation, environmental pollution and related health issues - through these discrete materials (their extraction, industrial production and use)?

Graham Harwood: We are just beginning theoretically to explore media systems and media ecologies. I've been irritated by Matt Fuller's work for the last 20 years, and as a practitioner always want to see what works and hopefully irritate him back some. I'm not an academic, not a theoretician, not an historian, but I do have respect for theory, and the history of ideas. But what excites me is the process of doing, that's how I explore the world. The histories, methods of practice, are not the same as the history of ideas in literature or critical theory, while it may borrow from, misread, or misdirect both.

Material is also a media. Tantalum, aluminium and coal contain physical properties; aluminium is lightweight, does not degrade and is easily recycled, but needs enormous amounts of electricity to turn the bauxite into metal. Tantalum, allows very high temperature compactors. Coal is combustive, releasing a force that can be measured and harnessed.

Image: Graham Harwood, Richard Wright & Matsuko Yokokoji, Tantalum Memorial, 2008

AI: In each instance the centrality of these minerals to post-industrial economies is threaded through the ‘social' application of technologies like search engines, telephony, databases etc. Could you talk about this relationship in terms of modelling and in terms of use?

GH: In the art space, or more usually on the boundaries of art, the works are contraptions made up of situations, peoples, geographies, networks, technicalities that bring the historical, social, economic, political into proximity with each other to create a moment of reflection and imagining.

The constituent parts usually operate in many contexts at the same time, technical journals, political groups, Congolese telephone networks, radio stations, Universities, schools, museums, curatorial practice, urban regeneration. I do not have any problem with creating media systems that have utility from my art methods. The utility, though, must reveal something about the nature of power in which its mediation is taking place. This happened with Telephony Trottiore or TextFM amongst many others or Jean Demars' Freemob.v

AI: In my understanding these projects could be described as producing ‘practical materialist allegories of materials'. Could you talk about how collaborative projects such as Telephony Trottiore, navigate vicissitudes between user communities, utility and the material relations of power?

GH: Matthew Fuller and I built TextFm in 2001. It allowed anyone with access to a mobile phone to send a message to a specified number. A computer received the message and read it out using a text-to-speech program. This speech was then broadcast by a radio transmitter over a specific geographical area. It was a way of creating a simple, lightweight, open media system by bolting together two simple components, radio and SMS. The media system then had to negotiate the placement of its transmitter of open content.

So the question: ‘Who could have open content?', was the first vector of power that the media system reveals, then the laws and regulations of radio transmitters, then the linear ordering of messages and the cost of each SMS and of course censorship. The object of a contraption like this is to watch it awkwardly unfold and reveal the conditions that surround it or are embedded within it.

Another more complex and long term project was Telephony Trottiore produced by Matsuko Yokokoji, Richard Wright and myself working closely with ‘Nostalgie Ya Mboka' a Congolese radio programme that goes out on Resonance FM.

Working with Nostalgie since 2003, we slowly got to understand that in Central Africa people defy media censorship using ‘radio trottoire' or ‘pavement radio' - the passing around of news and gossip on street corners. The system allowed people to pass a phone message on to another person, spreading like a grapevine or, as Richard Wright coined it, a ‘pass the parcel' model. At the core of this system is an automated telephony server that can phone people up at random from a database of phone numbers and play them any pre-recorded audio content. After being played a story, the listener is invited to join in by recording a comment on the clip they have just heard. They can also pass the story on to a friend by entering their telephone number on the keypad (which is then added to the database). This new user will then be dialled and can also listen, leave a comment and pass it on - building up a string of users like a daisy chain.

Once activated the system worked well and in the first six weeks we had 660 users and 58 percent chose to pass their stories on. As the system operated it unfolded into their use of mobile phones and the Coltan Wars, the most devastating yet least publicised conflict on the African continent. An ordinary device such as a mobile phone connects us not only by wireless transmissions but also through a process of globalisation that includes historical currents, technological proliferation and the traffic of refugees which we explored further by creating Tantalum Memorial.

AI: How do these projects depart from existing forms of ‘representation'?

GH: I don't do representation, I build contraptions for people to manifest themselves based on the cultural context of those people using them. I like to see what happens when different systems collide. As an example, the Congolese were not represented or pictured in Tantalum Memorial. Telephony Trottoire created an informational architecture that the Congolese community could manifest themselves in using their own networks - for me to represent this in an Art Gallery would have been unnecessary for obvious reasons. This was their content, their system. All the people in the gallery needed to know was that there was a more or less intangible telephone network, full of refugees from the Coltan Wars and it was triggering a set of redundant telephone switches historically invented by a funeral director.

AI: Though these projects do not work solely within a logic of ‘representation' they do, almost as a side effect, produce powerful images. I am thinking in particular of the film stills from Aluminium and the blackened lung hooked up to the the coal fired computer. If the ‘contraptions' you make can be thought of as diagrams of socio-technical relations, what are the qualities of the images they produce? To what extent are these images necessary by-products of the processes?

GH: We can see the images arising out of the forces that threaten to break the machine, or assemblages arising out of its in-betweenness. Its unfinished nature always requires the imagination of the participant/viewer to finish the job, fill in the details. This is a powerful strategy.

AI: Could you explain the process applied to the industrial films Metal in Harmony and Aluminium on the March?

GH: The work takes ‘The Futurist Cinema' manifesto from 1916 and turns it into a Perl programme and applies it to the still frames of Aluminium on the March and some American industrial footage in homage to the USA aluminium industries' historical support for fascism.

Image: Graham Harwood and Matsuko Yokokoji (YoHa), Coal Fired Computers, 2010

AI: There is a basic underpinning of this moving image residue in language, i.e. code, but could you also detail the application of language in the form of key words, search strings and how these relate to the process?

GH: The Aluminium book, was formed from my work with Raqs Media Collective for Manifesta07 in which I was looking into the media ecologies of the disused Alumix Factory in Bolzano, Italy. This meant I had to understand the geographical, political, social, economic forces at work to bring about Alumix and also its regeneration. So I did a lot of groundwork going over toxicology results, electrical power production, labour migration, futurism etc. I was immediately struck by the 20th century as the Futurist Century. How the atom bomb in all its awe and beauty acted out a futurist finale.

At the same time I constructed a Netmonster to track aluminium, and also used Richard Roger's Issue Crawler software to see what relationships companies with interests in the aluminium industry had to each other and governmental agencies.vi At the end of this process I did a word frequency analysis of the texts to find keywords that I'd scraped. I then sprinkled the words over each frame in the film, then each word/frame searched the internet for a sentence containing the word aluminium and the keyword.

I was interested again in this idea of the book as a machine, the Futurist relationship to aluminium. What would a 21st century narrative look like through an Essex Futurist's eyes? The Aluminium book is a completely logical construction but has no logical outcome.

AI: Through the application of these processes some sequences in the finished film and stills (from the publication) show workers merging with both products in the process of production and the tools used to shape them. In a sense this exposes the horrible reality of labour under capitalist production as expressed by Marx, that commodities contain labour power that is human sweat (the expenditure of the human body) congealed into value. To me the film sequences show this very directly and allegorically. Is this something you were interested in showing?

GH: I was interested to see what a largely pre-film Futurist manifesto would do to film of a Futurist metal. I'm interested in the things you speak of and have witnessed them in my family's health and conditions, but did not explicitly intend them and it would not surprise me if they are there. I'm interested in exploring the way the material transforms us as we transform it.

AI: What do you make of the contradiction between the history of the miners' strike - a struggle to perpetuate the mining of coal in the UK - and the aims of the latter day environmental movement to shut down the remains of coal mining in the UK?

GH: We still use coal, only produced under worse conditions, elsewhere, and its use is increasing globally. The miners were removed for bringing down two governments and having a vision of working class power that lay outside of governmental structures. How could we have had globalisation with such a vision intact?

Most mining in the UK is open cast which is terrible for the environment compared with deep cast mining which was relatively better but meant poorer profit under safe conditions. If we stop mining then we have no contemporary world, no copper wires, no phones, no electricity, no computers everything stops.

AI: How does the Coal Fired Computers project span these contradictions?

GH: Coal Fired Computers burns coal for its own sake, it is not outside the process. It is a self-induced crisis bringing those diseased humans, their activism into proximity with the engines that transformed them, linking to the conceptual engines, (databases, computers) that transform us as the steam engine transformed the Victorians to Empire.

AI: Do your contraptions also work in a different direction, so as to reverse, thwart or break the constitutive links between productive chains? Are your works interested in creating contraptions of resistance, of new bodies, of new lines of flight?

GH: I don't know, perhaps such projects don't really resist anything, as it just makes power flow down other lines of lesser resistance even though I used to think more of the term. I make contraptions to explore, see what happens, find out. If this dislodges, reveals oppressive practices, relations then good - but it's not my main intention. I just want to see what happens, support friends, feel scared, excited and embarrassed about what I make.

Image: YoHa, cover of Coal Fired Computers pamphlet, 2010

AI: A key interest in the Coal Fired Computers' project seems to be to do with bodies, making bodies of data present and showing the material deformation of bodies by industrial processes and work. Is this a preoccupation across several of the projects discussed here? How does this preoccupation with bodies shift in each project?

GH: There are a few preoccupations at play across the projects, one is the proximity of death to media. Contemporary media arises partly out of the reanimation of corpses with Galvanism, or trying to contact the dead through electro mechanical means (William Crookes, Cornelius Varley), or power generation and execution as exemplified in Blood and Volts, Edison, Tesla and the Electric Chair by T.H. Metzger, or death caused by resource wars, or how media ends up containing the dead in early films, sound recording, portraiture, books etc.

The second preoccupation is illness as an altered state in which work, and the normal relations to capitalism are not possible, which can manifest as a social, political, cultural force.

Then there are the machines that compose the body as they have been invented across time, the mouth machine, site of infection, social hygiene, health observatories. The systematic offering up of parts of our body to be reordered by authorities. The effects of the systematisation of contagion and its ability to transform our relationship with ourselves.

For me, a key turning point was the production of Lungs as a software poem memorial to the 4,500 slave labourers that worked in Hall A of the former Deutschen Waffen und Munitionsfabriken A.G. During the Second World War (now the main exhibition hall of ZKM). I computed the vital lung capacity of these forced workers from a set of Nazi records, a nascent database, then the program re-emited their last breath of air into the exhibition hall. I was interested in doing this on machines descended from Hollerith's punch card machines and exploring IBM's relationship to such conditions in helping the Nazis to process the slave workers.

AI: Mainstream media has recently begun to pay some attention to the constitutive role of the exploitation of cheap labour, particularly in China, underpinning the production of the hardware with which we interact on an everyday level: mobile phones, netbooks, Iphones, Ipads etc. This attention reveals something of the conditions of assembly and supply chains which produce and deliver these consumer goods, but stops short of the study of the energy generation which drives this production. Does your work close the gaps in this analysis? Is this a question of the form of an enquiry or its content?

GH: For me there is very little difference in coal, coltan, computing and the labour (sometimes forced) that produced them or their consumption, which can be seen to unfold into other forms of production. Without wanting to belittle the important distinctions you make between consumption and work, and the historical struggles this implies, I have a very different perspective that I approach this area from.

As I see it, all organisms negotiate with the medium in which they live and of which they are not entirely a part. This simple biological predetermination allows us to unfold the negotiation with media as a pathological or compositional influence on the human species and the construction of its power structures. From this, we can then speculate on its role as a force equal to other biological ones such as sex or the need to reproduce or acquire calories.

This perspective requires us to look at what kind of physical/conceptual machines exist within a given media system. What social, cultural, political, geographical forces were at play that enabled a particular media system to emerge, or be superseded at a particular time.

AI: How do the ‘media ecologies' you work with and create within overlap with the ecology of art itself? How does your approach resituate art and the artist on the edge of these spaces of art?

GH: This is a little complicated, as I hold hypocritical positions on art and media. I'm completely uninterested in people with loads of money hanging the absurd on their wall, validating it as a symbolic structure of taste.

The success of modernist or post-modernist art methodologies in the 21st Century have normalised art into the everyday universe of capitalist promotions, representations and the structures of power. In this more popular context, art has become a calming anaesthetic, warmly suffusing our social bodies, blunting the convulsions as everything goes critical. Art fills the gaps of economic Darwinism's lack of imagination - and in the UK, it's become a cheap panacea for social inclusion, economic regeneration, and the maintenance of an unfair world.

Having said this I find myself addicted to ‘art' as a space of reflection, a looseness that I cannot find elsewhere. In order to navigate this rupture in my thinking I make a somewhat artificial separation between between ‘art' and ‘art methodologies'. To clarify this: ‘Art' is the construction of conceptual images that allow those engaging with them to reflect on the current conditions that surround the art work. ‘Art methodologies' are skills and tools developed by artistic traditions, practice that can be applied, sold, traded with other specialisms to bring about potential social, material benefit.

This separation between art and its methods enables me to see where an artist's ‘professional' methods may be serviceable to the utility of communities of interest and wider social goals. It also clarifies where art can be seen within an ‘action research' agenda for a commissioning partner in which the artist becomes part of a community of practice, engaged within the process of progressive problem solving to help open up situations.

I usually use the art methodologies to negotiate a pathway. I'm sure many artists will shudder at such a definition of practice, but as I'm mostly interested in socially active aesthetics, I'll prostitute any art methodologies to smuggle myself into an interesting position to make my contraptions.

Image: Graham Harwood, from Aluminium: Beauty, Incorruptibility, Lightness and Abundance, the Metal of the Future, 2008

AI: How does the introduction of technology into the spaces of art conversely introduce a broadly critical attitude to media into the spaces of technology?

GH: Other than the introduction of electricity, software/computational culture is the largest media system that humans have known. Yet very little work has been done analysing the agency of algorithms, semiconductors or database management systems. We have very few cultural spaces, critical tools that allow us to understand multifarious ways in which these systems are unfolding into the present. Art as a construction implies reflection and so if you place some of these media-systems in that space it will be afforded some thought at least.

On the other hand most people working within database or software construction have no critical training. As an example there is no professional body for data analysts working in the NHS therefore no collective ethical standards or protection from an employer wanting an extra 0.0005 on some target figure, other then the programmer resigning. In my experience any introduction of art methodologies, or art as action research into these spaces is met with a huge sigh of relief.

Currently I'm working with a small number of NHS staff to understand how the conduct of an enterprise (an NHS Health Trust) is transformed by the modelling, creation and implementation of a database. I'm interested in what key stages of the database's technical realisation and implementation results in changed conduct and what the relationship is between the enterprise's changed conduct and the theoretical machine of the database management system.

So I'm working with NHS data analysts to help them use data visualisations/art methodologies in the production of informatics about poor housing and cancer rates and at the same time proposing contraptions as action research that will reflect critically on the acquisition of data and the monetary costs of giving birth.

Graham Harwood and Matsuko Yokokoji, YoHa (English translation ‘aftermath') <yoha.co.uk> , have lived and worked together since 1994. YoHa's graphic vision and technical tinkering has powered several celebrated collaborations. Harwood and Yokokoji's co-founded the artists' group Mongrel in (1996-2007) and established the Mediashed, a free-media lab in Southend-on-sea (2005-2008). In 2008 they joined long time collaborator, Richard Wright, to produce Tantalum Memorial winning the Transmediale first prize for 2009. Tantalum Memorial also featured at (ZeroOne Biennial San Jose - USA, Manifesta07 Bolzano, Italy, Science Museum London, Ars Electronica, Plugin Switzerland, Laboral Spain)

Anthony Iles <anthony AT metamute.org> is a freelance writer, editor and contributing editor of Mute

Info

Coal Fired Computing and Tantulum Memorial are showing at the Arnolfini, Bristol 25 September to 21 November, http://www.arnolfini.org.uk/

Full documentation of the projects discussed can be accessed at http://yoha.co.uk/

i Jean Demars, AV talk notes. Unpublished and courtesy of the author.

ii http://www.avfestival.co.uk/videos/harwood-talk

iii From the algorithm for the book reproduced in Aluminium: Beauty, Incorruptibility, Lightness and Abundance, the Metal of the Future, Bolzano: Manifesta, 2009. Available from http://download.mongrel.org.uk/aluminium.pdf

iv In a recent interview with Matthew Fuller, Harwood poses exactly this question in terms of the project around Aluminium: 'Did Italian fascism need aluminium, or did aluminium need Italian fascism?' http://www.spc.org/fuller/interviews/pits-to-bits-interview-with-graham-harwood/

vi Issue Crawler is a software that locates and visualises networks on the web, http://www.govcom.org

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com