Mistaken As Red

With political art now celebrated in galleries and museums all over the world what happens when practices tied to specific struggles and places are institutionalised? At the recent retrospective of textbook political artist, Loraine Leeson, Peter Suchin uncovers the remains of an earlier discussion intitiated by Art & Language to propose a radical reconsideration of Leeson’s art and the terms of the debate

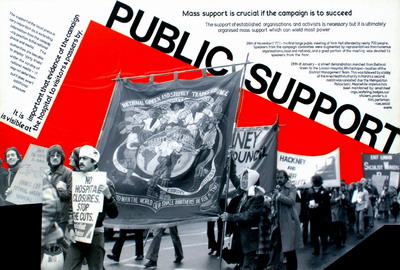

The recent retrospective of the work of Loraine Leeson at London’s SPACE studios, Art for Change, throws up a number of questions about the efficacy and even the desirability of something one might term, for the sake of convenience at least, ‘political art’. This is an issue to which I will return below. Based on a much more substantial exhibition organised by the New Society of Visual Artists in Berlin, 2005, the London show focused upon a number of key projects organised and executed by Leeson in collaboration with her former partner and colleague Peter Dunn. Extracts from and documentation of five periods of work were presented at SPACE: Leeson and Dunn’s involvement in the Bethnal Green Hospital Campaign (1977-78), that concerning the East London Health Project (1978-81), the Docklands Community Poster Project which ran for ten years from 1981, ‘The Art of Change’ (also 1981-1991), and cSPACE, Leeson’s still current concern, an organisation she founded in 2002. ‘The exhibition’, according to the accompanying leaflet, ‘celebrates Loraine Leeson as an artist whose work has influenced and supported social change for over thirty years. Leeson’s practice’, the text tells us, ‘is underpinned by a collaborative process which has involved health workers, trade unions, tenants associations, action groups, young people, schools and institutions, as well as other artists and professionals.’

A dense and detailed book, similarly celebratory in tone and intent, accompanied the display, its several essays predictably emphasising Leeson’s importance as an artist whose practice foregrounds discussion and collaboration over the apparently selfish idiosyncrasies of the artist working in the splendid isolation of the private studio.[1] Grant Kester, in his ‘Aesthetic Enactment: Loraine Leeson’s Reparative Practice’, certainly one of the most perspicacious essays in the volume, emphasises that ‘for Leeson the work of art only comes into existence through a process of consultation and reciprocal interaction with collaborators.'. Leeson’s work...’, Kester continues,

has been consistently produced in conjunction with activist groups…schools and, by and large, displayed outside of museums or galleries (on public billboards, in hospitals, community centres and other locations)…her work is unembarrassed by its alliance with broader struggles for social justice, and she views the complex negotiations involved in creating these alliances as an important part of her practice as an artist.[2]

What’s ‘political’ about Leeson’s practice then is not only its left-leaning subject matter such as working class struggles against hospital closures and the Thatcher government’s deracination of London’s East End, but also its very form of production as an acutely collaborative venture, its left-wing credentials being further bolstered by its repeated presentation outside non-art exhibition contexts.

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Exhibition Panel from Bethnal Green Hospital Campaign, 1977–78

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Exhibition Panel from Bethnal Green Hospital Campaign, 1977–78

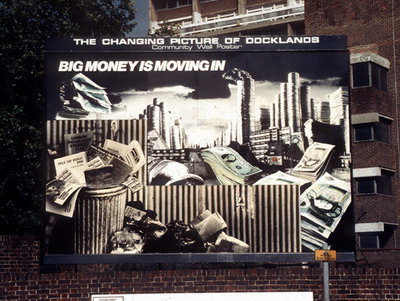

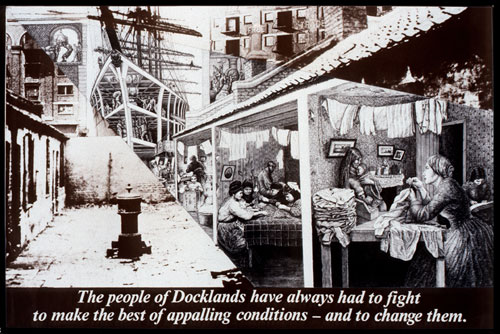

In his Postmodernism, Politics and Art John Roberts supplies a useful summary of one of Leeson and Dunn’s most renowned series of works, the Docklands Community Poster Project, claiming that these large scale photographic montages made in response to the Thatcher government’s plans to radically restructure and gentrify an immense tract of East London subsequently known as ‘Docklands’ had

a clear base in the struggles and experiences of the local working-class community. Working with various resident groups, the local borough, political pressure groups and individuals, Dunn and Leeson mapped out a shared knowledge of what were felt to be the most important issues affecting the community in its struggle against the development ... Measuring 18 ft by 12 ft and constructed from large photographic sections … the photo-murals combined various drawn and photographic elements representing various scenes from the labour history of the area and of the social consequences of the development … Unlike conventional hoardings or community murals … the posters were completed on a gradual basis so as to establish an active narrative interest in the work’s progress. As such the hoardings functioned as both an information board and as a symbolic site of resistance to the unbridled development.[3]

What this work showed, Roberts goes on to observe,

is how one of the most successful ways of building cultural alliances between artists and workers is to ally photographic practices with specific long-term political struggles. ... by bringing the skills and competences of many people into common focus, a raising of the real political differences within the community is brought into play ... [developing] in classic socialist democratic terms, organically from the constituency which it sets out to serve.

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Big Money is Moving in Docklands Community Poster Project, 1981–91

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Big Money is Moving in Docklands Community Poster Project, 1981–91

Roberts, an obvious supporter of the Docklands poster campaign, further notes that, irrespective of the apparently communal nature of this practice, it was Dunn and Leeson who ‘actually produce[d] the images and who invariably set the agendas for discussion.’ He sees one of the most important results of the project as being the deployment of photography as a ‘pedagogical community resource’, arguing that if consumerism destroys other knowledges, or rather the cultural spaces where they might be produced and exchanged, the active creation of a context where learning politically in the face of art might begin is genuinely progressive.

Roberts’ remarks point to several noteworthy features of the Docklands work, including its close alignment with the values of the people it was intended to serve and support and its emphatically didactic nature. His point about how it was Leeson and Dunn who physically made the posters and influenced their final formal disposition (as well as their thematic content) raises, however, various problems around the themes of the authorship and ownership of this practice. Whilst it is one thing for SPACE studios to present a range of works largely instigated by Leeson and Dunn over a 30 year period, it is quite another to contextualise the show with material that insists on its collaborative nature but then only place Leeson’s name on the wall in any prominent way. Many of the individual labels in Art for Change bore Dunn’s name too, but adjacent to the exhibition’s title at the entrance to the gallery was Leeson’s name alone. Similarly, although Dunn is represented in the publication his (I would think extensive) contribution is very much played down, his main presence there – apart from via the images he most certainly co-authored – being in the form of a four-page interview, and even this is ominously titled ‘Cuts of a Conversation with Peter Dunn’. Not only does there appear to have been an act of erasure involved in terms of the apparently considerable number of collaborators with Leeson who were mostly not named in any of the literature related to the exhibition, but the chief co-producer of the photographs, videos, posters and pamphlets Art for Change purports to represent received only the most minimal of billings.

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Whats Going On? Docklands Community Poster Project, 1981–91

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Whats Going On? Docklands Community Poster Project, 1981–91

This foregrounding of Leeson over all other participants seems most curious for a practice that heavily trades on its implicit critique of the conventional ideology of celebrity and the too often extant self-importance of the artist. At least in the book Leeson has the good grace to point out that when it came to working with a number of schoolgirls on a project that utilised Stanley Spencer’s painting ‘The Resurrection, Cookham’ (1924-27) as a point of departure for a major communally-executed work it was she, Dunn and Colin Grigg, the then head of the Tate Gallery’s education department, who selected the work without consulting their co-collaborators. Leeson was relieved, reports Carmen Morsch, ‘when the students accepted the painting for themselves.’[4] It was also Morsch who revealed, during a gallery talk at SPACE on the 19th of January, that about 90 per cent of the Berlin version of Art for Change had not been included in the London show due in part to lack of available room, but also because it was felt that in Leeson’s home territory of London much of the contextualising material presented in Berlin would be superfluous. But this was not the case; rather, a greater showing of the contextualising documentation from Leeson’s complicated and extensive practice would have made the practice itself look more like a series of interventionist strategies whose common thread was the visual image and its relation to text, instead of putting an artistic emphasis upon the works presented. As Art & Language (hereafter A&L) accurately stated in their seminal commentary upon socially-concerned art and its implications and ideologies, Art teachers may achieve quite a lot qua art teachers but not while they are pretending they are Artists, somehow determined in art history, not as society’s alternative ideologists, ‘imagists’, determined by the bureaucratic restrictions of their jobs … Exhibitions of art-for-people, love-the-people curators and help-the-people critics must be seen as essentially revitalisers of bourgeois subjectivist or idealist ‘disciplines’ …The result of socially progressive art ought to be less not more exhibitions, less not more experts on socially progressive art.[5]

Image: Installation view, Loraine Leeson: ‘Art for Change’, SPACE 2006

Image: Installation view, Loraine Leeson: ‘Art for Change’, SPACE 2006

This comes from an amended version of a paper given at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, in 1978 addressing various ‘socially-concerned’ exhibitions of the time, including Art for Whom?, held at the Serpentine Gallery, London, curated by Richard Cork, and in which Leeson and Dunn participated. Indeed A&L must be directly alluding to their work when they write

No verbal exchange, no horror-shock art work, no imitation of Heartfield, and a fortiori no smug managerial distribution of culture to the people will substitute for historical processes.[6]

The influence of John Heartfield can be clearly recognised within Dunn and Leeson’s work of this period and Leeson herself cites him as one of several German artists whose work was important for her when she moved to Berlin in 1975.[7]

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Housing Sequence Docklands Community Poster Project, 1981–91

Image: Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Housing Sequence Docklands Community Poster Project, 1981–91

As A&L also comically but pertinently point out in ‘Art for Society?’,

Britain is full of teachers pretending to be ‘artists’, ‘Artists’ pretending to be French Philosophers, curators pretending to be revolutionaries, etc., etc. Now bourgeois art teachers pretend they are socialist artists…It is the same recurring problem: the historical conditions they are really in are ignored in favour of the historical conditions they want, need, believe, feel intimidated into supporting, feel as though they ought to be in.[8]

A&L call the kind of people they are thinking of here ‘agents of bourgeois legitimation’ and it is not difficult to see why.[9] To make interventions (to use Leeson’s own term) into the dominant practices and conventions of art-making may have far-reaching effects but not if these are carried out as artistic acts which by definition retain the established hierarchies of expert and non-expert, artist and non-artist, ‘representer’ and represented. ‘One thing that is needed’, as A&L again acutely observe, is a workable, explicit distinction between the curatorial sphere of legitimation and the dialectical process of developing competence in the course of the class struggle.[10]

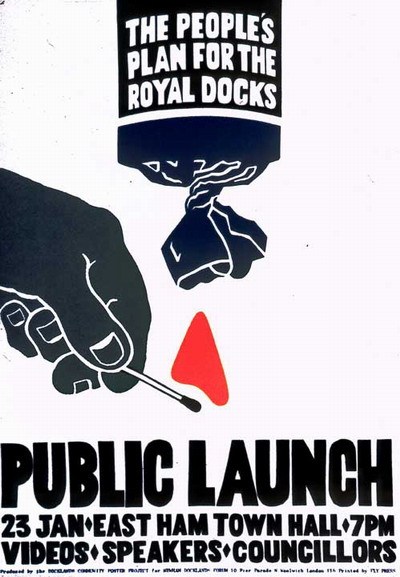

‘Art is marginal, to say the least, to active politics’, they add. Art for Change is an exhibition and publication that constructs an account of Leeson’s activities as being those of a significant artist, when her importance is in fact much more that of an influential teacher.[11] This is not to suggest that either she or Dunn are the ‘bourgeois art teachers’ described by A&L, but it is to emphasise that some kind of political and artistic readjustment was carried out in and around the exhibition Art for Change. Notwithstanding the importance of A&L’s critique of Cork’s 1978 show and the points it raised in direct opposition to the claims of critical purchase made then and in 2006 for practices such as that of Leeson and Dunn, no mention of this short but critically far-reaching text is made in the pages of the Leeson volume. Nor is much space given to other very relevant cultural operations such as that of constructivism in post-revolutionary Russia, when a number of artists began to think of themselves not as artist-individuals so much as workers skilled in the visual arts who could deploy their highly-developed technical abilities and intellectual interests in the service of a post-revolutionary culture. Image: Docklands Community Poster Project, People's Plan launch poster 1981–91

Image: Docklands Community Poster Project, People's Plan launch poster 1981–91

A third elision enacted by the Leeson publication involves Walter Benjamin’s famous essay in defence of ‘The Author as Producer’ (1934), in which Benjamin is at pains to stress not only the importance of the socialist artist acting within their practice in a manner involving an act of commitment to socialist principles, but also the transformative role of such a practice.[12] ‘What we must demand from the photographer’, Benjamin proposes,

is the ability to put such a caption beneath his picture as will rescue it from the ravages of modishness and confer upon it a revolutionary use value.[13]

He goes on to state that contemporary writers (who are the central subject of his paper) should themselves take photographs, thus progressively breaking down the established categories of ‘photographer’, ‘writer’, and ‘artist’. To destroy bourgeois categories of expertise is in Benjamin’s view itself a radical act. But in the latter-day context of Leeson and Dunn’s Docklands’ work the expertise and status of the ‘producers’ of the visual work offered in the service of socialist action against Thatcher and her agents is ultimately retained, and, in the display and publication connected with SPACE, more or less given back to these very authoritative ‘authors’. The work in question either was or was not collaborative and communal; if the former then to celebrate Leeson, and to a lesser degree, Dunn’s contribution is to enact a kind of oxymoron, a false claim of attribution and expertise.

Celebration is in any case itself problematic, notably when applied to visual practices. In their 1988 essay ‘British Political Art at Coventry’ Susan and Terry Atkinson raise a series of issues which bear more than a passing relevance to Leeson’s practice and career.[14] For one thing, they note, with respect to the already-cited spate of ‘political art’ exhibitions, that ‘It was predictable as long ago as the ‘Art for Whom’ exhibition that ‘dissent’ would become a pretty dull but useful commodity in capitalist culture in the late eighties.’[15]. This is because, as the Atkinsons elsewhere in their text explain:

Consumer society requires an acquiescence to established political authority – this is a truism, but one often overlooked by the self-regard and heated speechifying of conventional political dissent. Even as part of its consumer spectacle the politically established authority must have its managed dissenters as part of its cover for its own determination to resist any challenge to the maintenance of its sovereign power. Political artists, affirming and acclaiming their dissenting roles, are some of these delectable items of consumer cover.[16]

And also:

If the category ‘political art’ ever did have any critical function it should have been … to attempt to state the impossibility of affirming the political world in which we live. This would have required some cognitive competence, not to mention ingenuity. It seems obvious then that such disaffirmation will include the art world, and especially include the category ‘political art’.[17]

What is being argued for by Susan and Terry Atkinson is, then, not ‘political art’ but a practice that disaffirms the very culture that places art in a position of importance:

Criticising capitalism with the critical grounds that capitalism willingly and knowingly yields is neither here nor there. The minimum condition required is a critique that capitalism is strategically sufficiently unsure of as to have to make the effort, develop a new strategy, to appropriate the work.[18]

So-called political art is part of the problem of how one might develop a genuinely political practice involving ‘art’, not any kind of solution or answer to this ‘predicament’. [19] The pointing-up of the necessity of developing a critique that causes capitalism something of a rupture or substantial awkwardness, requiring it to develop new strategies of incorporation, is of interest when considering the formal status of Leeson and Dunn’s Docklands montages, which draw heavily on works issued 50 years before by John Heartfield. Such pseudo-Heartfields may have been easily legible to the workers who were involved in the protests against redevelopment but this ease of reading, the non-innovatory mode of address, is itself non-transformative. In adopting an already-established and uncontroversial visual convention it does nothing to extend the parameters of meaning within or around the visual work of art. Perhaps the ‘collaborators’ with whom Leeson and Dunn worked in the 1980s learned something about the history of art – about Berlin Dada and the political affiliations of some of the artists involved in it – but what was assembled and presented by Leeson and Dunn lacked the implicitly radical formal innovation that was one of Dada’s most important traits. Image: Installation view, Loraine Leeson: ‘Art for Change’, SPACE 2006

Image: Installation view, Loraine Leeson: ‘Art for Change’, SPACE 2006

In her essay in Art for Change on Leeson’s work as a teacher, ‘to take all that learning and put it together with all that art’, Carmen Morsch is keen to indicate that

After the change in government in 1997, the culture politics changed as well … [Today] the potential of art as a means for education and social inclusion has become the most important criteria [sic] for public funding of a project … What was in the ‘90s still unique [i.e. Leeson’s position as an avant-garde teacher] … now belongs more and more to the daily business of English art institutions, which today, can gain artists with an international reputation as collaborators for their educational projects.[20]

The passage is clumsily translated but its import is clear: artist-teachers such as Leeson are no longer in opposition to the official channels of education and culture but now operate in line with established models of induction into high culture. There is a perverse reading of Leeson and Dunn as avant garde artists here. I call it perverse because, although the concept of the avant garde is very much to do with instigating practices which are only later taken up within the mainstream, with therefore being in an important way ‘ahead of one’s time’, that term is also closely indexed to socialist values and to going against the grain of the established order, an order that is, in the literature of the avant garde, implicitly right wing. The paradox and perversion here is in the fact that the present Labour government is itself largely void of conventional leftist intentions. Though it may relentlessly prattle on about constructing an egalitarian culture, such a thing is precisely the opposite of what it in reality seeks to achieve. It is rather unfortunate, then, that Loraine Leeson’s current alignment with New Labour’s lip-service socialism can only serve to smooth – and indeed consolidate – Labour’s false image as promoters of equality, access and integration. Encouraging schoolchildren to make ‘art’ about their experience of disenfranchisement and exclusion is, intentionally or not, nothing less than the neutralising of dissent in advance of its potential manifestation.[21]

Loraine Leeson: Art for Change SPACE Studios, London, 11 November 2006 – 20 January 2007FOOTNOTES

1. Loraine Leeson, Art for Change: Works from 1975 – 2005, Neue Gesellschaft fur Bildende Kunst, Berlin, 2005. Although Leeson is given as sole author on the book’s cover it is in fact an anthology of writings and interviews by diverse hands (hereafter referred to in the notes as Art for Change).

2. Ibid., p.76.

3. John Roberts, Postmodernism, Politics and Art, Manchester University Press, 1990. This and all other quotations from Roberts in the present essay are from pp. 97 – 98 of this volume.

4. Art for Change, p.124.

5. Art & Language, ‘Art for Society?’, in Art-Language, Vol. 4, No. 4, June 1980, p.9.

6. Ibid., p.7.

7. Art for Change, p.10.

8. A&L, pp.8-9. One does not wish to belittle the role of teaching as a means of interrupting received ideas about culture or about the meanings to which specific works are attached. One way of doing this might be to look in detail at how specific visual works are assembled, unpacking, in discussion with one’s students or pupils, the various devices utilised in the making of the work. Roland Barthes’ essay ‘Rhetoric of the Image’ (1964), included in his Image-Music-Text (Fontana, 1977) is paradigmatic in this respect, as is Judith Williamson’s Decoding Advertisements (Marion Boyars, 1978).

9. Ibid., p.9.

10. A&L, p.1.

11. Ibid., p.3.

12. Walter Benjamin, ‘The Author as Producer’, in Walter Benjamin, Understanding Brecht, NLB, 1973.

13. Ibid., p.95.

14. Susan Atkinson, Terry Atkinson, ‘British Political Art at Coventry’, in Terry Atkinson, Mute 1, Galleri Prag (Copenhagen), 1988.

15. Ibid., p.18.

16. Ibid., pp.17-18.

17. Ibid., p.18.

18. Ibid., p.18.

19. Ibid., p.18. See also Terry Atkinson, ‘Predicament’, in Terry Atkinson, Brit Art, Gimpel Fils (London), 1987.

20. Art for Change, p.128.

21. For a discussion of the neutralising of dissent with respect to the broader sphere of philanthropic and charitable institutions, see Demetra Kotouza, ‘Lies and Mendicity’, Mute, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2006, also available at http:www.metamute.org/en/lies-and-Mendicity

Peter Suchin <petersuchin AT yahoo.co.uk> is an artist and critic. He has contributed to Frieze, Art Monthly, Variant, Untitled and many other journals.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com