Micro vs Macro

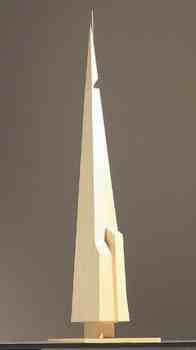

Are plans to alter London's skyline with a rash of flash new skyscrapers while simultaneously solving the key-worker housing crisis with portable micro-flats the sign of confused urban planning or the symptom of something else? Austin Williams reports  >> Architectural model of London Bridge Tower by Renzo Piano [ http://www.rpwf.org ]The issue of micro-flats – small modules for urban living – has hit the headlines recently, posing as the answer to the crisis in affordable housing. Designed by Piercy Connor Architects, the 32m2 flats are so small that they were modelled in Selfridges’ shop window. Some commentators have likened these flats to the small capsule crash-pads in Japan. But in reality, their most notable exponent, Kisho Kurokawa, intended places such as his Nakagin Capsule Tower to be temporary accommodation, additional to, not in lieu of, a main family home.

>> Architectural model of London Bridge Tower by Renzo Piano [ http://www.rpwf.org ]The issue of micro-flats – small modules for urban living – has hit the headlines recently, posing as the answer to the crisis in affordable housing. Designed by Piercy Connor Architects, the 32m2 flats are so small that they were modelled in Selfridges’ shop window. Some commentators have likened these flats to the small capsule crash-pads in Japan. But in reality, their most notable exponent, Kisho Kurokawa, intended places such as his Nakagin Capsule Tower to be temporary accommodation, additional to, not in lieu of, a main family home.

Meanwhile, just as the small-is-efficient (if not exactly beautiful) debate is being had, the other mainstream argument is about tall building: should we be building upwards instead of sprawling outwards?

Given added piquancy by the events of September 11, the tall buildings debate has been stimulated by the rash of high-rise proposals in the UK. From Renzo Piano’s London Bridge Tower, Foster’s Swiss Re, the Heron Tower, Citygate not to mention Birmingham’s Holloway Circus Tower to Portsmouth’s Millennium Tower, now even Croydon has skyscraper aspirations.

So it might seem that we have contradictory architectural advocacy; on the one hand local, small and domestic, while on the other, high-rise, corporate and globalist. While this dichotomy has existed for many years between different architectural schools and competing client interests, it is more interesting to note that today’s debate is more public and political – and more uncertain than before.

Actually, the difference today is that the debate is about the debate. Much is being written about what should or shouldn’t be built, but very little is actually getting built to get upset about in the first place. We have the lowest levels of house building since the war (and if you ignore the war economy construction boom, the lowest levels since 1924). In parallel to this, commercial firms are tightening their belts and increasingly risk-averse shareholders are less keen on new build and are turning to refurbishment.

Underlying this debate is a general mood of anti-consumptionism. Refurb is more ‘sustainable’ than the profligacy of new build; large houses generate more carbon dioxide than small houses. If our expectations for housing are too high, maybe we should reduce our aspirations a little bit, goes the argument. If overt expressions of corporatism are bad, then maybe we shouldn’t advocate tall buildings which reflect it.

Obviously, the UK is still a dynamic economy which will continue to build for different sectoral requirements, but what we build, and why, is becoming more uncertain.

Renzo Piano says that ‘we need to move from growth to sustainable growth; cities should move from explosion to implosion.’ Expansion bad, contraction good! In this respect, the tall building/micro-flat debates are two sides of the same coin.

On a political level, there is a lack of conviction. Admittedly London mayor Ken Livingstone seems adamant in his defence of skyscrapers, realising that he would like his tenure in office to be marked by some landmark buildings since he has signally failed to impress on any other level – but the timidity continues around him.

Whereas the legitimisation of tall buildings used to rely on simple factors like whether it worked, simple aesthetic judgements, and the commercial arrogance of the client, we now seem to have a confusion and a denial of the merits of all three. Today high-rise buildings are presented as eco-friendly structures, minimising their footprint and hence reducing their ‘detrimental’ impact on the city – effectively justifying a skyscraper on how small it is. No wonder Piercy Connor takes it to heart.

It wouldn’t be so bad if the micro-flats were temporary prefabricated units in which to house people while swathes of London’s Dickensian dereliction were demolished and rebuilt to modern-day standards. Instead, the micro-flats are being proposed as the answer. If the argument for decent housing has been lost what’s to stop space standards being further eroded – in the name of densification?

As long as architects justify their projects as having nominal impact on the urban environment, tall buildings will be no challenge to small-thinking. For example, Chris Wilkinson of Stirling Prize winning architects Wilkinson Eyre says: ‘It is a pity that many of our man-made structures are so heavy and monumental. I prefer the aboriginal concept of treading lightly on this earth.’ Somebody out there is probably designing the micro-skyscraper!

Architects should stop celebrating the natural environment. Whether that means building big is for individual architects and related professionals to decide; but at the very least they should start thinking big again – challenging social, infrastructural and environmental constraints, rather than kow-towing to them.

Austin Williams <AustinWilliams AT construct.emap.com> is an architect, technical editor of the Architects’ Journal, director of the Transport Research Group and columnist with the Daily Telegraph

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com