Make Representation History (G8 Report)

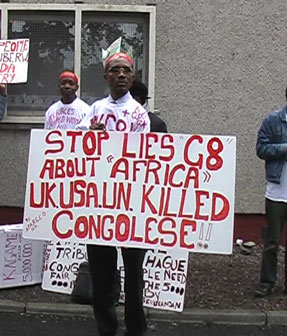

The Live8 concert may have been a spectacular recuperation of the anti-globalisation movement, but anti-capitalist protestors outside the G8 summit in Gleneagles were still trying to get the revolution televised on their own terms.

Mute's anti-representational guerilla media unit, complete with borrowed DV cam, reports back from the hills around Auchterader; East London Autonomous Media (ELAM) interview a protest facilitator about consensus decision making; and Hari Kunzru gives us a critical diary of the protests and examines the limits of specular protest

Interview with a facilitator (available as video and audio, see links below)

An interview with Lisa Fithian, US based activist and one of the facilitators at the ‘Spokes councils’ of the Stirling Eco Camp. Interview by East London Autonomous Media (ELAM) http://elam.omweb.org/

Spokes councils are a way for making consensus in larger groups, where smaller groups come together to make shared decisions. The groups each have a representative called a ‘Spoke’. The role of the facilitators is to encourage and support the consensus process in the spokes council gatherings.

The interview looks at the roles and history of horizontal consensus decision making processes in the organisation of the groups making up the anti-capitalist movement in the US.

The interview took place at the Eco-Camp ‘Hori-Zone’ in the Rural Convergence Space, Barrow Meadow Farm, Stirling. It is part of a series of reports by ELAM covering the resistance against the G8 2005, Scotland.

.mov http://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/g8facilitator.mov

.mp3 http://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/g8facilitator.mp3

Additional G8 video clipsInterview with a direct action protesterhttp://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/Interview.mp4

Gleneagles protest 6th JulyG8 alternatives bus arrive at Auchterarderhttp://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/busarrive.mp4CIRCA http://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/clownarmyvstate.mp4Gleneagles fence comes downhttp://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/fencedown.mp4Demonstartion in field surrounding Gleneagleshttp://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/demofield.mp4

After the London bombs 7 JulyEco camp kids - moments silencehttp://3d.openmute.org/uploads/g8/kidsilence.mov

Outside the Fence: A report from the Gleneagles G8 protests

The terrain

The G8 meeting is located at ‘the Gleneagles® Hotel … a Five Red Star golf resort set in 850 acres of stunning scenery in Perthshire, Scotland.’ The hotel is in a rural area, with very little transport access, the type of location which has become typical for such meetings since the Seattle protests of 1998. For the purposes of the G8 meeting, a five mile perimeter fence has been erected around the hotel. Persistent rumour has it that Michael Eavis, organiser of the Glastonbury Festival, has acted as a security consultant to the authorities. Residents of nearby Auchterarder have been issued with security passes, as the perimeter cuts through the Northwestern part of the village. The area is also being excepted from various ordinary legal contexts. The government has, for example, signed a blanket exception to Freedom of Information legislation for all matters relating to the summit. The police are using special provisions under the Prevention of Terrorism Act to stop, search, photograph and demand proof of identity from anyone travelling through the area. For information about rights of protest see http://linkme2.net/4u

For the protestors, the local geography is inspirational, not in a Romantic sense, but as a source of possibilities for action. They have converged in Edinburgh and the 'hori-zone', a camp located at the edge of Stirling town, behind an industrial estate in the bend of a river. Stirling is about fifteen miles across the Ochil hills from Gleneagles. Part of the campsite is an old landfill which gives off methane, so smoking is banned there. The river is wide and fast-flowing. Hand-painted signs warn of the dangers. Across the river looms an escarpment, on which is sited the Victorian gothic Wallace monument, site of one attempted G8 action. Police helicopters hover above the camp for much of the summit, a high whine, accompanied by the deeper rumble of twin-rotored army chinooks. Nearby runs the M9, one of the routes towards the Gleneagles hotel, which on Wednesday is the site of a blockade in which many blockaders are arrested.

The road blockades

Sir Bob Geldof (who in some media quarters is perceived as the sole activist voice) labels the blockaders 'thugs'. No context for their action is given in the mainstream media, which has already been saturated with images of a masked protestor taking a swing at a policeman with a bit of two by four at the previous day’s Edinburgh march. For the protestors the direct action strategy (insofar as such a disparate group can be said to have a single agreed strategy) is to prevent access to the summit. However this has not been clearly articulated, even to many of the participants, and to many people commenting afterwards on Indymedia and other broadly sympathetic sites, the blockade actions appear incoherent and confused. A video showing blockaders fleeing into a field, where they are trampled by stampeding cows and threatened by a hammer-wielding farmer, attracts ridicule and derision. Little attempt is made by the activists to explain the blockades to the outside world, and while they are ‘successful’, in that they cause serious traffic disruption for much of the first day of the summit, in most quarters little distinction is made between them and acts of vandalism in Stirling town directed against Burger King, The Bank of Scotland, cars and private houses. To join the blockades many people, fearing that the police will surround the camp, decide to head into the hills for the night of Tuesday-Wednesday, some carrying very little equipment. The next day support teams are still picking up cold and soaked stragglers, who haven't made it to their destination.

About the G8 blockades (how to): http://linkme2.net/4v

Eco Village

On the day before the blockades Stirling is quiet, and some local councillors (ties off, short-sleeved shirts for that 'casual' look) come on-site to shake hands and bid the protestors welcome. They've stuck their necks out to have the camp in their town, a decision which attracts bitter local criticism after the events of Wednesday. The community is organised according to a barrio system, a horizontal structure in which local groups take charge of their own area, plan actions, set the tone (early to bed or sound-system on late?), and send representatives to camp-wide ‘spokescouncils’. It's a temporary autonomous zone in which meetings are run according to a consensus decision-making process (see the Wikipedia article on ‘consensus decision making’ for numerous links) which gives no overall control to the vocal or those in a numerical majority, takes a long time to work (but does work for many kinds of decision) and tends to release information in a strange non-linear swirl, highly confusing for people whose first language isn't English. In other activist camps, translation is given a high priority. Here, because of the usual Anglophone laziness about language, translation is a weakness, which leaves some activists isolated and exposed. One Spanish photographer is illegally arrested and his equipment confiscated. He doesn’t know his rights, and little information was available to him.

In the camp there are systems for such things as security and fire procedure but not everyone knows them. Groups work on sanitation, media communications, building walkways and welcoming new-comers, with various degrees of skill and success. If you want to know something, you need to ask around, then sift through the various opinions and snippets of information to glean a picture of the position. At night voices cry out for volunteers to man the main gate, and slurred arguments take place – about noise, tactics, the acceptability of the word 'cunt' – to the accompaniment of helicopter rotors and distant sirens. At 2 a.m. on Thursday morning the camp is surounded by armed riot police. Someone goes round calling out ‘wake up, wake up’, but doesn’t mention why. Most people ignore the call and only discover the situation in the morning.

The camp is definitely 'action-oriented'. There are few workshops and little organised political discussion. People are here to do stuff, to cause problems for the G8 meeting. Everyone realises that the site is infiltrated by the police, press and security services. Afterwards, the Scots Daily Record will publish the ‘diary of an anarchist’, written by a journalist who ‘infiltrated the anarchists, then lived and marched with them.’ The ethic at the camp is no names, no pictures, no mobile phones in meetings. People who break these rules are severely censured. Actions take place off-stage, planned among barrios and affinity groups, see Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affinity_groups . Many people are rumoured to have set up camp offsite in the hills, so as to avoid potential police blockade.

The Gleneagles March

We have to approach via a torturous (but picturesque) series of backroads, as the police are blocking all obvious routes to Auchterarder. We see them stopping obvious protestor vehicles on roads just outside Stirling, but because we are in a rental car, we are relatively invisible. At a road block we are ‘advised’ to turn back, but the policeman’s ambiguous wording makes it clear he has no power to stop us proceeding to the demo if we can find an open road. Nearer to the village, we are stopped at another roadblock and the vehicle is searched, but they don’t open a bag containing climbing equipment, which might have caused us problems.

In Auchterarder, the atmosphere is expectant. Older people, in particular, are very excited and friendly, and we fall into conversation several times. Some residents are looking forward to a carnival, waving from windows and laughing. Others seem nervous. A shopkeeper gives an interview to a woman who identifies herself as a journalist from the Sunday Times. ‘The atmosphere is electric,’ he says. ‘Everyone who comes in seems very nice. We’ve done excellent business.’ Elsewhere local newspaper headlines shout ‘Auchterarder braced for anarchy’, and a delicatessen advertises the ‘G8 pie’. ‘Mince because they talk it, dumplings because they are.’ At midday (after a nice cup of tea) we walk up the high street of ‘the Lang Toon’. Many shops are boarded up, the boards flyposted with (presumably ironic) sheets reading ‘Welcome to Scotland’ and ‘Scotland the Brave’ in a variety of languages. Almost all other windows have ‘make poverty history’ flyers displayed in them. It becomes apparent that this is code for ‘please don’t break this glass’.

We’re directed to the local sports ground, where yellow bibbed stewards from the G8 Alternatives coalition (which includes unions, peace groups and CND) direct people towards a stage from which a soundsystem is playing The Proclaimers, good authentic working-class Scottish music. ‘And I would walk five hundred miles / and I would walk five hundred more…’ Someone from the fireman’s union is speaking. We’re promised AL Kennedy and George Galloway as celebrity speakers. There’s a light drizzle, which adds to the depressing nature of the scene. There is a sense of constraint, tedium. Very few people seem to have turned up, hardly surprising given the difficulties of access. Then we find out that police have been boarding coaches in Edinburgh and Glasgow telling people the march has been cancelled. There’s a great deal of vocal anger about this obvious dirty trick, and it seems the police have had to back-track rapidly from their statement, announcing that they’ve ‘decided to let it proceed’ while carefully avoiding the question of their right to unilaterally ‘cancel’ it in the first place. We are told that more protestors will be arriving, but because of the police and the blockades, they’re likely to be late.

Soon bus after bus starts to draw up outside, and the crowd swells. Press photographers run around taking pictures of the bicycle-powered sound system. They’re particularly interested in a piper, who at one point is completely surrounded by camera-wielding hacks. CIRCA (the Clandistine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army) are there in force. They dance around to the Proclaimers, accompanied by a nuclear family of mummies, mummymummy, daddymummy and babymummy. A vicar on a bike gives press interviews. He looks like a real vicar, rather than a fancy dress one. At least two other soundsystems arrive and start to compete with the ‘official’ PA. It becomes apparent that among the protestors there are widely-differing pictures of what we’re doing here. There’s the SWP/G8 alternatives version, with branded banners, an orderly march to the fence and the rather insipid prospect of ‘making our voices heard,’ as more than one speaker puts it. A lot of people express discontent that ‘ownership’ of this situation is in the hands of this group, and a desire to subvert it is one of the impulses behind later events.

I notice some of the press photographers are carrying climbing helmets. Expectation of disorder is clearly high, though there’s nothing to suggest it as the crowd gathers in the park. AL Kennedy doesn’t show, but we get a download of Galloway, who orates in trademark fashion, is duly acclaimed by the crowd, and mobbed afterwards. The march moves off, with Galloway and a group of G8 Alternatives activists at its head. We walk through Auchterarder, banging drums, blowing whistles and doing the usual march-type stuff. It rains intermittently. At length the march arrives at a line of fencing, behind which stand massed ranks of police, those at the front wearing hi-vis jackets, those behind them in riot gear. All have earpieces taped to their ears – one large police network, a cybernetic show of force.

Galloway and others make speeches to a bank of broadcast media. No attempt is made to address the crowd (in any case not a particularly practical prospect, since it is now estimated to be around ten thousand strong) and many marchers start to express discontent, feeling that they have been turned into a back-drop for the utterances of a small number of professional organisers. The socialist-oriented groups who called the march wish to appear to control a large bloc of organised, disciplined people, a platform from which to make demands and gain access to power. Autonomists and others who have joined the protest without any allegiance to the organising group (or respect for their strategy) consider this a kind of hijack. Being produced as a mass, a crowd, a force to be wielded by vanguardist leaders, is not to everyone’s taste. To many of those present, a demonstration, with its drama and its concentration of energies, is a site for self-expression (costumes, noise etc.) and for behaviour released from constraints of discipline, whether exerted by the state or the political agenda of any party organisation. This tension between representation (who speaks for me?) and constitution (How do I choose to act, what do I choose to be part of?) runs through many events during the G8 mobilisation.

The speeches made, the leaders evaporate. From now on, things become much more random. According to the agreed narrative, the march will now turn a corner and head back into town along a planned route. However, confronted with a fence and a line of stern-faced policemen, many marchers don’t wish to move on. They’re fascinated, preoccupied with taking snapshots, shooting video of all the people (police and media) who are shooting video of them, or simply facing off against the cops, staring at them, cat-calling, asking them whether they’re on overtime. Coherent political agendas (and certainly the agendas of the professional politicians who have come here to assert their ownership of dissent) are beginning to dissolve into something playful, confrontational, temporary and local.

The march is backed up down the road. Some of us turn the corner, and find ourselves in a space that seems eerily like an arena. A row of substantial houses stands opposite a field of green corn. Far off, across the field, is the now-mythical fence. Behind it, as if to draw the eye, is a line of mounted police in riot gear. Just visible behind them is the Gleneagles media centre, a glimpse of a white marquee and a row of flagpoles. In the front drives of several of the houses are giant cranes. Sky TV cameras occupy one. A group of observers (probably police) occupy a second, and another tv crew the third. The only thing separating the official route (back down the road into town) from the field is a low barbed wire fence. People mill about, looking at the mounted police. A few CIRCA clowns fool around, trying to get the cops to smile. Then, inevitably, one black-clad guy jumps the fence and walks off into the field, to the accompaniment of loud cheers. He is followed by another couple of lads who take an ostentatious piss, one repeatedly shouting ‘Make Poverty History’ in a loud Scots accent. Since that’s the official Geldofite slogan, it seems unikely these characters are political radicals. From the way they’re dressed I buy them as local boys along for the ride, here out of some blend of conviction and boredom.

There’s a level of intrigue about the G8 among younger local men. At a roadblock, earlier in the day, we walk forward to check out the situation and are hailed by battered van full of lads, who ask whether we’re ‘off tae Gleneagles.’ ‘Gain fe a bit o’ bother?’ they ask, grinning and making the thumbs up sign. At first we think they’re protestors, but they’re wearing site clothes, and there’s a copy of the Sun on the dashboard, not favourite reading material at the Stirling camp. They say they hope we have fun, and drive on towards the police line.

Soon there are half a dozen people in the field. Then twenty. Then a hundred. Police make a half-hearted attempt to stop more people entering, but they don’t seem that concerned. No one is heading back to town. Some of those in the field decide to head on to the fence. The confrontation is set, and escalates rapidly. An American flag is burnt, a Palestinian one hung on a tree. Briefly people break through, throwing sections of fence at the police, who retaliate with batons. Reinforcements are flown in in Chinooks which buzz deliberately low over the crowd. The effect is very Imperial, very Star Wars. Vans pull up. By now the stewards are screaming at people to get back onto the road. One woman (maybe an organiser) shouts sarcastically ‘oh very good! Very good! A bunch of hippies in a field! What do you do now, you idiots? You’ve ruined it! You’ve ruined everything!’ We hear later, from some very angry people, that the stewards round the corner have despaired of the situation, and deliberately split the march, sending those in the rear back to town on the route they already followed. This is considered by some would-be confronters to be a betrayal – with more bodies the push through the fence might have been successful. One steward is visibly upset that people are facing off against the police. ‘You shouldn’t do that! These are working-class men. They’re doing their job!’ Protestors jeer angrily at anyone in a yellow bib. No one is in control.

What is later reported as a ‘running battle’ is more a giant game of grandmother’s footsteps, as the majority of the trespassing crowd, who wish to defy the police but not actually fight them, judge their advances and retreats by the likelihood of getting a crack over the head. The star-wars quality of the police hardware, and the ‘insertion’ of reinforcements by helicopter seem designed to cow the protestors, but instead the excess has the effect of confirming the David and Goliath nature of this combat, displaying the massive investment in maintaining the existing order of things. The game in the field takes an hour or so, and proceeds without mass arrests, excessive force, or much in the way of provocation. Compared, for example, to the level of violence at the Orange order march in the Ardoyne on 13 July (blast bombs, baton rounds), it’s pretty low-key. Tabloid phrases later applied to it (‘knife wielding anarchists’, ‘officers, stretched to the limits’, protestors ‘storm[ing] nearby crop fields’ – all from the Daily Mirror coverage of Thursday 7 July) imply a degree of savagery that is simply not present.

Images

The mobile phone and the DV camera have become vastly important as tools of protest. Now that mobile telecoms allow people to transmit audio and video from situations where they are physically constrained (such as within a cordoned-off protest camp, or at the crush in front of a demo), the conditions of silence and darkness which afford the opportunity for certain kinds of official abuse are less easy to produce. In the Stirling camp, video is shown of illegal arrests in Edinburgh, conducted by police who are not wearing numbers, and refuse to identfy themselves. This could become the basis for a court case. Just as the police are constrained, so are the protestors. Independent media footage is now frequently used to identify and prosecute activists. At the G8, the police shoot huge quantities of all kinds of imagery. Mini DV’s are in the hands of many uniformed officers. Broadcast-standard material is shot by plainclothes people in the crowd (some carrying press passes). We see a man dressed in black clothes, with a black and white Palestinian keffiyeh wrapped round his head, in the thick of the confrontation at the fence. Later he is behind police lines, downloading pictures to a laptop and (we think) transmitting them via a sat phone to his handlers. At the Stirling camp, people wishing to leave are photographed and some are placed in front of a large handheld black camera, whose lens is divided into quadrants. From the way it is deployed we believe it may be linked to a biometric system, as police appear to be using it to match faces to a database. They empty some people’s bags, spread their clothes out on the ground, and photograph them too.

Protest in the form it takes at Auchterarder has a specular logic. Without media visibility it is not particularly effective, except in changing the consciousness of participants and observers. Mainstream media has a tiny repertoire of acceptable imagery – the masked Black Block activist, the carnivalesque clown, and so on. At the Auchterarder demo, a young Scottish guy (very possibly the one who was shouting ‘make poverty history’) runs back from the fence, blood running from a wound above his hairline. He screams at anyone who will listen that he was attacked by police while calling out ‘peaceful protest’. He is pointed in the direction of the press photographers, and duly appears in the Mirror and several other national daily papers, metal chain and whistle round his neck, digital camera in hand. Apart from the blood, he could be any suburban raver. Later he is spotted wearing an enormous bandage, with dried blood carefully left on his face to maximise his wounded-soldier look.

The sight of riot police is itself highly aestheticised, particularly for a generation which has grown up with the romantic imagery associated with 1968 and the New Left. More than one person, watching the mounted police advance across the field, mentions that they are reminded involuntarily of the work of the artist Jeremy Deller, who in ‘The Battle of Orgreave’ (2001) reconstructed a confrontation between police and striking miners. Inside the camp, the no cameras-no phones rule underscores the refusal of the specular in direct action situations, in which anonymity is vital, and its promotion in demonstrations, which are now primarily machines for the production of media content. Crossing the police line at Stirling (getting searched, recorded, your details entered into a database) is a transition into involuntary specularity. However, the camp is far from being a media black hole. Walking around, one frequently hears people lying inside tents, talking on mobile phones, privately briefing people (Press? Friends?) on what’s happening.

After the terrorist bombs in London on Thursday, the press are no longer interested in G8 protest of any kind. Certain types of action, directed at gaining media attention, are no longer viable. This invisibility is not fully understood by some people in the Stirling camp, who expend a great deal of energy on actions such as a ‘climate alert’ (making a lot of noise with drums and other instruments), predicated on media attention. There is tension between those who wish to observe restraint out of respect for the London dead, and those who feel it is important to assert the right of protest in the face of the police blockade. Silent vigil or attempted break-out? Banging drums or lighting candles?

The idea of a press release also takes up a lot of time, but due to the difficulties of getting agreement on even the most basic wording, it never becomes a reality. A working party, consisting of representatives of various groups within the camp, are deputised to produce a draft. Since everyone is aware of the difficulties of the project, and since anything longer is unlikely to be reported in full, it is agreed to restrict a statement to a three line minimum. A stand-up meeting of 25 people, working to a time-limit, manages unanimously to agree a wording. ‘We are saddened by the bombs in London. We are here protesting at the G8 to work towards a world free from violence. All bombing is terrorism.’ The group feels it is particularly important to make some kind of link between ‘state terrorism’ (the invasion of Iraq, principally) and the kind of action perpetrated by the London bombers. This, says one speaker, is all that differentiates the activist position from the kinds of statement already emerging from the mainstream media. Indeed the refusal to accord a special legitimacy to violence conducted by state actors is the primary point of difference between the Stirling camp activists and mainstream liberals. If violence is reserved as a right of the State, then, for example, IDF bulldozers are legitimate and Palestinian stone-throwers are not. Unravelling this distinction is very important to many in the camp, especially a group of International Solidarity Movement activists, who use the Israel-Palestine situation as their primary point of moral reference.

When the statement is brought back to the main spokescouncil, it is picked apart. A long meeting dissolves in acrimony. A group of German autonomists feel that any reference to a ‘world free of violence’ suggests that their tactics of violent confrontation are unacceptable. One member of the drafting group makes a passionate speech trying to explain his belief that it is possible to use violent means to work towards a non-violent state of affairs. ‘I’m not a pacifist,’ he growls. ‘I support the Zapatistas. I supported the IRA. I think some people here are just trying to underscore their anti-liberalism at the expense of the matter in hand.’ An adult speaking for the ‘childrens group’ asks why we can’t just release a statement calling for ‘love and peace.’ She is openly jeered. Various people try to come up with alternative wordings on the fly. One man is adamant that ‘violence’ should be replaced by ‘abuse’, for reasons not immediately obvious. Many people dislike the sentence ‘all bombing is terrorism.’ Some appear to be animal rights activists wishing (perhaps) to defend ALF firebombs. Others are pacifists, or people who wish to draw moral distinctions between various kinds of violence. Several people walk out. Some groups sign up to a version of the wording leaving out this sentence. Others refuse, and express anger, believing that any statement will be taken as representing the position of the whole camp. In the end, a signed statement is delivered to the media group, then someone (possibly in a deliberate attempt to short-circuit the process) tells them the meeting has decided against releasing it. The discussion has taken several hours. The media have all left for London anyway.

Sir Bob

Bob Geldof is called on by the mainstream media to comment on every aspect of G8 lobbying and protest, even those with which he has no connection and little understanding or sympathy. He has no time for the activists, and does not acknowledge that the movement he heads is only viable because of the global consciousness-raising achieved by the social movements in the years since Seattle. His ubiquity irritates many people, while his simplistic presentations of the situation (more charming back in the ‘give us yer fucking money’ ‘80s) and his frank sycophancy towards his new world-leader buddies have ceased to wash, even with the NGO crowd who put up with him in the hope that Live 8 would force serious concessions. For months before the meeting he has crowded out more eloquent and intelligent voices. However it is undeniable that the Live 8 project has ensured blanket coverage of debt relief, which would not otherwise have happened, and as a result has educated many people to the economic realities of globalisation. After the meeting he attempts to put a glorious spin on the G8 results: a good-but-not-extraordinary debt agreement, the very disappointing measures on trade and the total lack of movement on climate change. NGO representatives are sharply critcal. War on Want and the World Development Movement issue a joint press release: ‘Bob Geldof's response to the G8 communiqué is misleading and inaccurate. By offering such unwarranted praise for the dismal deal signed by world leaders he has done a disservice to the hundreds of thousands of people who marched in Edinburgh at the weekend. His comments do not reflect the collective conclusions of the development campaigns who make up Make Poverty History. Mr Geldof has become too close to the decision makers to take an objective view of what has been achieved at this summit …Bob Geldof may be content with crumbs from the table of his rich political friends. But we did not come to Gleneagles as beggars. We came to demand justice for the world's poor. We have no problem with Geldof celebrating the successes of the Gleneagles summit and the 10 million lives he feels will be saved as a result of this deal. But what about the other two billion people driven into poverty by the policies of the G8? Did the leaders of the rich world have nothing for them?’ Geldof brands all criticism of the deal a ‘disgrace’, and asks for ‘perspective’. The NGOs start to talk about the ‘suspension of disbelief’ they had to practise in order to participate in the Geldof-Bono show. Who is seeing clearly?

The main achievement of Live Eight is educational, though its ‘consciousness-raising’ role is mitigated by the way it produces a giant moment of simulated redemption, the suggestion made to all the finger-clicking kids that by going to see Coldplay, they are actually changing something, instead of providing a media-friendly gloss on a slate of pragmatic debt-relief measures which would have been taken with or without Live Eight – and which, soon after the summit, will be quickly watered down by the introduction of ‘technicalities’ such as the attempt by EU members to tie debt relief to structural adjustment measures – economic deregulation, privatisation of utilities and so on, the usual neoliberal prescription. Perhaps the anticlimax will make a proportion of the new Live 8 public question the effectiveness of their participation.

By 8 July, the G8 has made Geldof history. Meanwhile rumours persist that large amounts of record company cash and ‘hospitality’ have been deployed to influence the choice of acts for the Live 8 bill. Who profited from Live 8? Yahoo news reports that in HMV’s 200 British stores Pink Floyd's ‘Echoes’ album posts a staggering 1,343 percent increase in sales on the Sunday after Live 8 compared with the same day the previous week. The band’s guitarist Dave Gilmour announces that he will donate these extra royalties to charity. Other acts hurry to follow suit. While many of the performers are doing the right thing with their 10 percent of CD cover price, how many of their record companies are doing the same with their much larger proportion? A list of the big Live 8 album sales winners, sourced from Amazon, can be found at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/4651309.stm/

Representation, constitutionLiberal democracy has the notion of representation at its core. At the G8 ‘We’ are offered all sorts of representatives. Tony Blair. George Galloway. Bob Geldof. Many people in the protest movement reject the notion of representation altogether, arguing instead that the only adequate representative of the population is the population itself. The wish for a kind of non-sovereign power constituted by the collective ‘will of the multitude’ is behind various aspects of the culture of G8 protest, from the scrupulously non-hierarchical, non-majoritarian decision making in the camp to the anger at the presumption of those leftists who presume to act as the voice of those standing behind them in the march. This, of course, is in addition to a more fundamental kind of disgust, directed at the system which gives eight powerful leaders the power to set the rules by which millions live and die around the world. At the Auchterarder march, George Galloway calls, echoing the rhetoric of other speakers, for the marchers to ‘make your voices heard’. This is received with lukewarm cheers. The poverty of the very notion of ‘voice’ lies at the root of this. Politics, for many in the social movements, isn’t verbal or representative, but embodied. It is something you are and do, rather than something you say. Understood in this way, the camp is an important form of political action, an attempt to live in a certain manner, without certain kinds of restriction. Likewise the experience of protest (as opposed to its results, or even the ‘cause’ for which it is undertaken) is itself understood as political, politicising. Within the demo, despite it being an intensely surveilled space, libidinal energies are released. The very proximity to the police is important to some protestors. The police are, after all the arch-representatives, the state embodied in each uniformed, de-individualised figure. The experience of defiance is understood by some as a liberating act, adequate in itself as a route towards a free selfhood, and hence a free future. A key slogan for this view is the tag sometimes attributed to Emma Goldman: ‘if I can’t dance it’s not my revolution.’ Much activist visual rhetoric uses the image of dancing in front of police lines or drawing lipstick shapes on perspex riot shields. This position (experience as an end in itself) is fiercely criticised by others as the substitution of ‘kicks’ for a genuine programme of change, an outlook which reduces politics to an essentially masturbatory activity, protest as pleasure, as leisure: camping at Stirling as an activist holiday. The CIRCA clowns, who adapt traditional buffon techniques to confrontational direct action situations, are experts in producing and manipulating certain kinds of affect, raising the spirits of frightened or tired marchers, defusing conflict and reproducing the oh-so-serious forces of law and order as absurd and excessive cartoon figures. They seem to function in exactly this area of libidinal, experiential protest. The heritage for their kind of politics goes back towards Situationism and the Dutch provo movement. Within the space of a violent demonstration, there is no doubt that they are a welcome presence. However one socialist commentator sarcastically remarked when shown pictures of their action at the G8, that ‘the maturity and strength of a movement is in inverse proportion to the number of clowns.’ There is grumbling on Indymedia that they are becoming celebrities. The churn continues.

Hari Kunzru

Credits

Video: Jaya and Raquel

Images: Hari, Raquel and Simon

Additional images can be found at http://linkme2.net/4t

Thanks to Saul

What is ELAM?

East London Autonomous Media (ELAM) is a loose collective of media makers formed at the G8 2005, neither corporate or independent. If you'd like to get involved or contribute, see http://elam.omweb.org/

Copyleft: please redistribute and credit

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com