The Last Picture Show

The strategy for Lottery funding of the arts in the UK could be summed up as follows: ‘If you build it, they will come.’ As the recent closure of the Lux Centre suggests, however, it takes more than shiny new buildings to sustain a dynamic cultural sphere. Benedict Seymour wanders through the ruins

OUT OF THE PAST

A long time ago in a galaxy far far away, two artist run cooperatives were set up to further their specific interests – promoting artists' film and video, sharing equipment, preserving and exhibiting their work. These organisations, the London Film Makers Co-op, established in 1966, and London Video Arts (later London Electronic Arts), set up in 1976, had their own different politics vis-à-vis the commercial worlds of art and cinema. Occupying a marginal position but creating their own constituencies, both survived to enter a very different cultural universe.

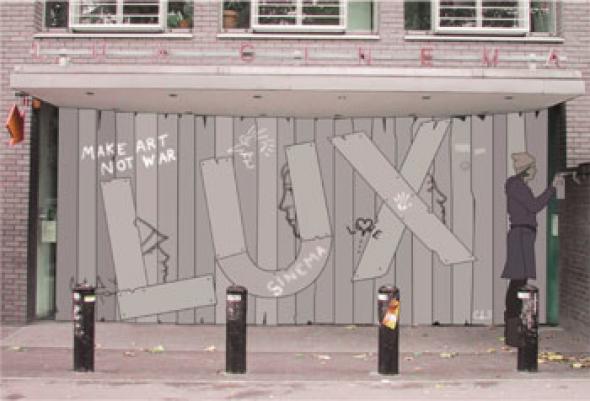

In October 1997 the organisations’ brand new state of the art home opened in Hoxton Square. Promising new opportunities for artists, filmmakers and their audiences, the Lux Centre appeared to many of the locals (not to mention the original constituency of the organisations) as an alien spacecraft from the planet Lottery Funding. Nevertheless, it was a spacecraft with the potential to escape from the increasingly narrow definition of culture that was emerging elsewhere in Blair’s ‘Cool Britannia’. Now, four years later, the Lux has been precipitately shut down, its staff turned out (without warning or severance pay) onto the street.

The Lux’s demise is a massive and signal blow to the already badly eroded independent exhibition sector in London. Along with its cinema and gallery, post-production facilities and training courses, the Lux was also Europe’s largest distributor for artists’ film and video. For all the shortcomings of the cinema – inadequate seating, duff air conditioning and a lack of public space – the Lux represented a unique intersection of cultural activities: the gallery hosted work by artists using electronic media, and the cinema showed film and video from the centre’s archive and around the world, much of which would not otherwise be seen in the UK.

NEVER GIVE A SUCKER AN EVEN BREAK

Death by gentrification was the initial verdict, the story an art house whodunnit in which ungrateful landlords, eager to reap bigger rents, oust the tenant who helped make the area fabulous in the first place. The reality is more complicated, however. In fact, the Lux’s rent problem goes back to the original lease negotiated by the British Film Institute with the developers, Glasshouse, in 1996. The lease tied the BFI in for 25 years, with no break clause, and upwards only rent reviews every five years. But since the BFI had said in writing they would offer LEA and LFMC three years of rent support, this does not seem to have caused an obstacle. With the creation of the Film Council in May 2000, the BFI experienced budget squeeze and the devolution of its funding responsibilties. Despite complaints from the Lux’s Board of Directors, the BFI peremptorily reneged on the agreement, leaving the Lux with an £80,000 bill.

If the original lease was a timebomb for the Lux, it was obviously a coup for the landlord. In the name of ‘creative use’, they created a flagship property using public money from the lottery and from regeneration-hungry Hackney Council. If the BFI and their lawyers were thinking at all when they made the deal, it was more as property developers than as guardians of culture. ‘Stuck’ with an increasingly expensive building in one of the most astronomically gentrified areas in London, once the BFI finds a new tenant they could be onto a nice little earner. If the Tories intended the lottery to act as a stimulus to the construction industry, the Lux’s rise and rapid fall would seem less an aberration than a case of mission accomplished. Like an ad hoc Private Finance Initiative, the Lux can now take its place alongside Railtrack or the Tube PPP as an instance of public money subsidising private gain in which the alibi of service rapidly succumbs to mismanagement and congenital unviability.

The LFMC and LEA’s lack of experience and the novelty of the lottery scheme probably explains why they never attempted to buy a building outright. But even if they had this would not necessarily have saved the Centre from another curse of the lottery: the over-estimation of audience figures and revenues that the lottery assessing officers encourage arts organisations to make.

From the first the Lux was excessively optimistic about its commercial sustainability. In particular the failure of the post-production facilities, rendered unpopular by the rise of home editing and their lack of positioning in the market, made them a millstone rather than a moneyspinner. In miniature the Lux exhibited the same symptoms as other bigger lottery failures – Sheffield Centre for Popular Music, the Cardiff Centre for Visual Arts or the Dome. Money was there for the buiding, but the vision, coherent planning and ongoing financial support to ensure its long term sustainability ware missing.

THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL

The Lux's problems did not end with the original lease, however. Structurally underfunded from the start and doubling up on core functions, by late 1998 the LFMC and LEA were forced to merge. This may have rationalised the Lux's operations somewhat, but any benefits were outweighed by serious mismanagement, poisonous internal politics and a general problem of information flow. Along with fear and frustration behind the scenes, the Lux also suffered from its constituent organisations' historic aversion to the kind of showmanship and self-promotion deployed by more 'successful' cultural institutions. Lacking the entrepreneurial acumen of Philip Dodd's ICA, the Lux failed to establish the 'commercial-creative synergies' dictated by inadequate public funding.

Fast-forwarding through three years of shameful mismanagement, communication failure and institutionalised inertia, by the time the Lux's accumulated problems reached a head there was still no contingency plan in place to save it from the rent timebomb. Downsizing and radical reconfiguration were essential to salvage at least some part of the Lux's activities but this, too, escaped the management's grasp. Because of the Lux's information vacuum, it wasn't until after the precipitate departure of its director, Michael Maziere, in November 2000 that the Lux discovered how broke it was. Turning to the Arts Council for life support, the organisation was submitted to its Recovery Programme. Keeping the Lux functional in the face of impending insolvency while a panoply of expensive consultants assessed its financial situation and future options, it took nearly a year and cost the programme £280,000 to divine that the Lux could not be made viable in its current form. The remaining budget was insufficient to reconfigure and re-establish the Lux elsewhere, and the Arts Council would not release yet more money for this purpose. Suddenly the Lux had no future at all, rent rise or no rent rise.

WE DON'T WANT TO TALK ABOUT IT

Internal difficulties and commercial problems aside, the Lux was ultimately the victim of the incoherence of arts funding policy. The Lux’s interdisciplinary character as a meeting point for diverse media and practices should have been its USP but it also allowed funders to see the Lux as someone else’s problem. Potential champions from both the film industry and arts end of the spectrum seem to have lacked conviction about the Lux, and were all going through crises of their own. Just as financial support for the Lux disappeared in the transition from the BFI to the Film Council, the devolution of the Arts Council’s core funding functions to a network of regional arts boards created another policy hiatus in the area of ‘Visual Arts’ where the Lux was working. For some reason the Arts Council won’t let their staff talk to journalists, but their press department point out that it is not the funders’ job to run the institutions they subsidise. They also point to a number of individual ‘moving image’ projects that they have funded. However, this does not amount to a coherent policy for artists’ film and video, nor is it enough to outweigh the experience of practitioners ‘on the ground’.

As for the Film Council, they remain transfixed by the Holy Grail of making another Lock Stock, and see the BFI as far too left field. The Lux didn’t even show up on their radar. When their policy for ‘cultural cinema’ appears in January 2002, it is likely to match their conception of ‘cultural film-making’: a politically correct absolution for all those (bombing) blockbusters. This means feature films with subtitles and feature films that deal with themes of disability, race, sexuality or gender. The huge gulf between what the Lux was doing and the Film Council’s understanding of ‘cultural cinema’ is one thing that looks unlikely to close.

With the forced exodus from New Labour’s bathetic grands projets already begun, the challenge now is to discover a ‘third way’ between the unaccountable bureaucracy that consumed the Lux and the culture pimping that sustains the ICA. If anything good comes out of the eclipse of the Lux it will involve creating a better, viable and contemporary form of the autonomy sought by the original cooperatives a long time ago, in a galaxy far far away.

Benedict Seymour <ben AT kein.org> is a writer and filmmaker based in London. He is currently working on a film about regeneration and housing in London with Year Zero films

Former Lux director Michael Maziere comments on this article in Mute 23 Letters

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com