Laboured Enthusiasm

Marysia Lewandowska and Neil Cummings' recent project at the Whitechapel Gallery presented 'communist' era Polish amateur film clubs on the terms of 21st century gallery display. Tom Roberts reports and tries to separate the workers from the bosses

Where artists and writers on the left in the industrial period were consumed with the problem of representing capitalist and socialist relations proper to an industrialised society, today we return to that time in search for models to help us think about immaterial production, and its function in what we now call symbolic economies - forms of labour and value which are apparently more difficult to measure and represent. Marysia Lewandowska and Neil Cummings' ‘Enthusiasm’ project makes an example of the amateur film clubs (AKFs) that developed among workers in the People's Republic of Poland from the 1950s to the 1980s. Sanctioned (with reservations) by the state, which provided film equipment and space through the workplace, amateur film took on a relative autonomy: the clubs were networked into a competitive structure organised among producers, but with input from professional bodies. What Lewandowska and Cummings invest in the AKFs is the potential for spare time to become ‘productive’, in a more or less antagonistic relation to the demands of the workplace, the market, and consumer culture. Industrial production in an ‘actually existing socialist state’ lends the artists a supposedly rigid structure against which to pose the model of an unofficial productivity.

The artists' investment in the model of the AKFs is informed by anxieties about the indeterminacy of contemporary social relations, specifically those of the cultural producer. In the background of this project is the tragic representation of post industrial society: old industry is said to have ‘migrated’, the potential of the working class as a political body gone with it; leaving us supposedly without a model for social agency to pin our hopes to except atomised consumer choice. On the other side of this apparent break, cultural industries are seen to be rising from the ruins of old industry; or rather, in most cases plonked on top of them from above, reproducing the mechanisms of social distinction while appearing to release us from the shackles of organised labour. That this process of reproduction is often as much a feature of ‘critical’ culture is the central problematic of ‘Enthusiasm’.

The exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery forms part of a wider project, taking the culture of the AKFs into both art institutions and the distributive legacy of open source. The various forms the artists initially envisaged the project assuming reveals great possibilities that unfortunately could not be developed: Cummings and Lewandowska initially considered inserting the collected films into the archives of the former state media in Poland. However, they found that these had been privatised and currently charge large fees for access, leaving, as they point out,

‘a large part of the cultural memory of a nation, which the state produced, is now denied to the very people who contributed to it.’

This is very unfortunate, it could have provided just the right ‘dominant context’ for situating the films, and would perhaps have had a transformative effect to a certain extent on the old media archive in itself. Instead, the artists decided to place the collection in what they perceive as an oppositional space, in the public domain via a web database under Creative Commons licences. We should be sceptical about viewing the public domain, and Creative Commons in particular, as the benign flipside of the privatised archive, but in this case we will have to wait to see how the online database pans out.

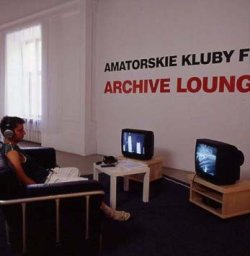

So far, ‘Enthusiasm’ has appeared has appeared in two institutional contexts, at Warsaw's CCA in 2004 and now at The Whitechapel Gallery, London. The films are shown in three themed ‘cinema’ spaces and an ‘archive lounge’ in which the audience can browse through DVDs left out of the curated selection. A hanging of posters produced by the clubs, and the reconstructed interior of an amateur film club's social room rounds off the display, which is arranged in an open plan manner in the lower gallery. The range of film subjects and approaches is diverse, as is the level of ‘sophistication’ employed by the film–makers; to an extent the artists have levelled the field in selecting films, choosing award-winning shorts alongside efforts that, at first glance, resemble home movie footage. Some films stand out for their formal and thematic sophistication - like P. Majdrowicz's ‘docudrama’ of unrequited gay love, Nieporozumienie (1978), or K. Szafraniec's animation Karuzela (1984) - which implies an initiation into high culture, or a rapid appropriation of its apparatuses of judgement. Though the paucity of information available on the film–makers rather than their collectivity as members of the group makes it difficult to make such propositions. It might have been easier if we had been given an idea of the respective positions of the film–makers, in terms of their roles in the factory and extent of their prior experience with film. The level of aspiration to the dominant culture, or to professional film culture as practiced outside Poland, is also difficult to generalise about. But the programme printed for the films rewards some of them with plaudits borrowed from professional film culture: ‘masterfully shot’, ‘a wicked satire’ and so on.

So far, ‘Enthusiasm’ has appeared has appeared in two institutional contexts, at Warsaw's CCA in 2004 and now at The Whitechapel Gallery, London. The films are shown in three themed ‘cinema’ spaces and an ‘archive lounge’ in which the audience can browse through DVDs left out of the curated selection. A hanging of posters produced by the clubs, and the reconstructed interior of an amateur film club's social room rounds off the display, which is arranged in an open plan manner in the lower gallery. The range of film subjects and approaches is diverse, as is the level of ‘sophistication’ employed by the film–makers; to an extent the artists have levelled the field in selecting films, choosing award-winning shorts alongside efforts that, at first glance, resemble home movie footage. Some films stand out for their formal and thematic sophistication - like P. Majdrowicz's ‘docudrama’ of unrequited gay love, Nieporozumienie (1978), or K. Szafraniec's animation Karuzela (1984) - which implies an initiation into high culture, or a rapid appropriation of its apparatuses of judgement. Though the paucity of information available on the film–makers rather than their collectivity as members of the group makes it difficult to make such propositions. It might have been easier if we had been given an idea of the respective positions of the film–makers, in terms of their roles in the factory and extent of their prior experience with film. The level of aspiration to the dominant culture, or to professional film culture as practiced outside Poland, is also difficult to generalise about. But the programme printed for the films rewards some of them with plaudits borrowed from professional film culture: ‘masterfully shot’, ‘a wicked satire’ and so on.

In common with Jeremy Deller (whose ‘Folk Archive’ is currently showing at the Barbican Gallery, London), Cummings and Lewandowska's work is a combination of ‘horizontal’ engagements in the public realm - itself a contested set of spaces - and gallery displays which seem to exist to validate the artists' practices in the eyes of funding bodies. Whether this weakens the engagement across the board is open to question. The Warsaw exhibition, by most accounts, dealt with the relations between the amateur film–makers, the state and industry; it had a chance to invoke partially buried but still accessible cultural memories, and was accompanied by events including the participation of some of the film makers themselves. In its transition to the Whitechapel Gallery, the contextualising focus seems to have been lost to an extent; the visual display has become the centre of gravity, no doubt partly a contingency of working with the Whitechapel, an institution that prefers to privatise the experience of discursive modes - transforming, for example, its reading room into a coffee table and plastic sofa set up - on the periphery of the 'show'. Here, the amateurs' practices have been given a different positioning in line with the development of the project: the exhibition marks a shift from the world of the ‘enthusiasts’ to the discursive territory of ‘Enthusiasm’.

While it is a burden to reheat questions of institutional critique in a period in which institutions have apparently dissolved or devolved to whatever extent, by branching into gallery displays, ‘Enthusiasm’ at the Whitechapel can't really avoid them. There is an argument to be made that a certain degree of status within the institutional structure allows for interested artists to turn the conditions of judgement around. Artists like Cummings and Lewandowska have to triangulate with the demands of the institution, the public and other potentially critical voices; the ethical standards of their work are offered through statements of the care taken in working with their subjects, but we really need to see the process of research in motion to judge this, otherwise they amount to the equivalent of the ‘direct from local growers’ label on a pack of fair trade coffee. There are two problems with this: firstly, that the amateur’s aspirations or otherwise to the status of ‘artists’ is likely to have been more differentiated than a simple inversion of values can accommodate; and secondly, that the pre–emption requires the economic and political conditions of amateur production to be thoroughly modelled if the process of recuperation is to be disrupted. Given that it's a tendency of contemporary culture to remove the agency of workers from the historical process of industry, or otherwise pose worker's lives as separate from the social relations of work itself, the lack of detailed information on the relationships between the amateurs and the workplace is disappointing. Take the recreation of an amateur film club's social room, presumably once housed in a space provided by the factory, a positioning of the amateurs' practices that provokes and pre-empts the conferrance of 'official' legitimacy on them, in slight antagonism to the legitimising structure of the institution. This severs the space from the recognition of the amateurs' former benefactors, and so the relationship between the amateurs and their roles as industrial workers - vital for understanding the richness of the amateur film culture - is de–emphasised in favour of a parodic recoding which jokes about the new patronage the enthusiasts can enjoy.

How might we open up a critical space that has been obscured in the current implementation of ‘Enthusiasm’? The best way would be to consider the historical processes of legitimation and autonomisation that the exhibition brings to light: amateur work, however 'personal' in its pursuit of curiosity, always exists in a relation - of aspiration, antagonism, or both - to the structures that govern the conferrance of legitimacy on practices: the school, the workplace, informal systems of judgement, the art institution, the state. What's certain is that ‘Enthusiasm’ is not a pure motivational force: its very nature is in its interestedness, an engagement with the game which might be more or less unencumbered by the pursuit of financial remuneration, but in which much is nevertheless at stake.

.jpg) Amateur film was among a wide range of leisure activities organised for workers by the PRP. Attitudes to film clubs differed, some sociologists believing that the active pursuit of cultural production might be a self–interested diversion of social energies; another position asserted the attention to curiosity had a subversive effect, in terms of a deeper, more critical social penetration. Hanging above the provision of film equipment, then, were questions of trust in the enthusiasts in the eyes of the state; it would be good to know what conditioned access to film equipment in different circumstances, particularly as, to paraphrase Lucasz Ronduda, ‘Enthusiasm’ represents the amateurs as ‘a proletariat of film, gaining control of the means of cultural production.’ The situation was arguably more complex than that, but his analogy at least points to the process by which access to the material apparatus of film-making brought the amateurs into contact with a second order of productive means, concerned with the production of belief in and among producers and their work. An understanding of this process is complicated by the status of various ‘external’ bodies in the wider structure of the AKF network. It appears that figures from the media, professional film–makers and of course the factory management were involved to differing degrees with the judgement of amateur films. It is clear that the values of amateur film making came close at times to a symbolic inversion of those inscribed in it by the factory, and by extension the state. As Stefan Skryzypek of AKF Radok says in an interview with Marysia Lewandowska:

Amateur film was among a wide range of leisure activities organised for workers by the PRP. Attitudes to film clubs differed, some sociologists believing that the active pursuit of cultural production might be a self–interested diversion of social energies; another position asserted the attention to curiosity had a subversive effect, in terms of a deeper, more critical social penetration. Hanging above the provision of film equipment, then, were questions of trust in the enthusiasts in the eyes of the state; it would be good to know what conditioned access to film equipment in different circumstances, particularly as, to paraphrase Lucasz Ronduda, ‘Enthusiasm’ represents the amateurs as ‘a proletariat of film, gaining control of the means of cultural production.’ The situation was arguably more complex than that, but his analogy at least points to the process by which access to the material apparatus of film-making brought the amateurs into contact with a second order of productive means, concerned with the production of belief in and among producers and their work. An understanding of this process is complicated by the status of various ‘external’ bodies in the wider structure of the AKF network. It appears that figures from the media, professional film–makers and of course the factory management were involved to differing degrees with the judgement of amateur films. It is clear that the values of amateur film making came close at times to a symbolic inversion of those inscribed in it by the factory, and by extension the state. As Stefan Skryzypek of AKF Radok says in an interview with Marysia Lewandowska:

‘We would usually film a report that we were asked for but there was always a lot of 8mm footage left over. One day we started looking through it, editing it together. We made a separate film and called it ‘Celebrations'... shown, so to speak, through the back door. The film was simply made in conspiracy...’ http://csw.art.pl/entuzjasci/

The film–makers have pointed out that the Mayday parades and other events which the clubs were asked to record by the factory were rarely sent into competitions; they had an inverse cache to the films produced in the clubs' own interests. We might identify here the formation of a symbolic economy, of the kind described by Pierre Bourdieu as operating on a ‘loser wins’ logic in relation to the principles of the dominant culture. There is an irony in this development, in that state sociologists perceived amateur film making as ‘an activity, which at the very core lays a complete creative – as well as reproductive act’1 with the suggestion that film might reproduce the experience of industrial labour, thereby bringing the workers back together with the processes from which they had been alienated. In moving film culture into a more or less autonomous relationship to the state, the film–makers began to reproduce the terms of the new valuing structures they encountered, and partly constructed. Kieslowksi's Camera Buff, showing on sundays at the Whitechapel for the duration of the exhibition, offers a lucid account of this self-reflexive tendency. The film follows the trajectory of one enthusiast through the process of awards, screenings, professional advice and pressure from the factory management. Filip Mosz, the budding amateur film maker, returns to the ever growing film club in its space provided by the factory, having had his film shown at a competition where the judges declined to award a first prize after TV's Andreij Jurga suggested: '

'Television has a duty to show certain things. You have no such duty; that is your strength. I can't believe your life consists of meetings, ovations, parades... On the other hand, I'm sure you can make films about yourselves, and your workmates who work really hard to keep us all fed.'

Having already begun to experiment with a film that records the endless digging up and covering over of a hole in the pavement opposite his flat, Filip finds his actions confirmed; he then (assuming an authoritative stance) takes it upon himself to offer his friends at the club a new criteria for the production of films:

'We need a different approach: we should make films about people, about our feelings, our experiences.'

This sequence shows us how cultural producers internalise the shifting value of what is expected of them, and apply this to their practices, based on the level of belief in the valuator. Where the amateurs' gradual embodiment of the stakes of production - both industrial and cultural -becomes an expropriation, in line with the needs and desires of the enthusiasts and those around them, and where it is a reproduction generating a new order of social distinction, is complex and difficult to measure; What is interesting is where these valuing systems, the legitimating bodies of the AKFs and the state, the artists and the institution, meet and interact, sometimes awkwardly. The diplomas and lovingly handcrafted statuettes that line the walls and cupboards of the recreated club room stand in for a whole history of endorsements, a system apparently alien to the values of the gallery in its ready materiality, its investment in proof that the films and film makers were believed in. AKF culture having been devalued through its association with the patronage of the former state, there is a sweet irony in this display, as if the certificates were waiting in a modest and vain attempt to influence the rehabilitation of the films on their terms. But this valuing system has ultimately been presented for evaluation in itself, a strategy that would only be usefully disruptive if the values of the gallery had been put under judgement at the same time. Whether they are allowed simply to supersede the former is a major point of contention.

The functioning of AKF culture in an economy of belief, and the tenuous legitimacy of the amateur film–makers, leaves this historically determined model open to projections from within the symbolic economy of the international art world. It appears that Cummings and Lewandowska have not attempted to block their own projection onto the enthusiasts. They approach the object of their research with an openly declared interest - in the amateurs, and in the research process itself, which symbolically belongs to another discipline - that closes in on the amateurs in a (self) reflexive circuit. Celebrating the absence of consecration in the disciplines they allude to, they play on the possibility of the artist as a more or less professionalised, more or less consecrated enthusiast, following his or her interest in an ‘informal’, self–motivated process of learning which is subject to the imperative to display his or her findings at given intervals: here, the artist embodies a knowledge of the object of his or her enthusiasm; it functions as a form of institutional credit, validating the display. This inevitably limits the possible choices artists make from the field of history; a sense of what is expected of them - values of motivation, aspiration, interestedness - not to mention the pressure to consolidate research in a visual display - informs the criteria for selection, in a projection of desires and anxieties onto the space of unofficial production. In fact it might be suggested of Cummings and Lewandowska that they offer these ‘virtues’ for evaluation; they move them centre-stage. Of course, the real difference between the artists and the amateurs is in their respective access to more legitimate systems of valuation; they occupy very different positions in the social world.

The functioning of AKF culture in an economy of belief, and the tenuous legitimacy of the amateur film–makers, leaves this historically determined model open to projections from within the symbolic economy of the international art world. It appears that Cummings and Lewandowska have not attempted to block their own projection onto the enthusiasts. They approach the object of their research with an openly declared interest - in the amateurs, and in the research process itself, which symbolically belongs to another discipline - that closes in on the amateurs in a (self) reflexive circuit. Celebrating the absence of consecration in the disciplines they allude to, they play on the possibility of the artist as a more or less professionalised, more or less consecrated enthusiast, following his or her interest in an ‘informal’, self–motivated process of learning which is subject to the imperative to display his or her findings at given intervals: here, the artist embodies a knowledge of the object of his or her enthusiasm; it functions as a form of institutional credit, validating the display. This inevitably limits the possible choices artists make from the field of history; a sense of what is expected of them - values of motivation, aspiration, interestedness - not to mention the pressure to consolidate research in a visual display - informs the criteria for selection, in a projection of desires and anxieties onto the space of unofficial production. In fact it might be suggested of Cummings and Lewandowska that they offer these ‘virtues’ for evaluation; they move them centre-stage. Of course, the real difference between the artists and the amateurs is in their respective access to more legitimate systems of valuation; they occupy very different positions in the social world.

The artists' identification with the enthusiast might, in part, provide an explanation for the privileging of amateur film clubs over other forms of organised leisure on offer in state-communist Poland. While Lewandowska and Cummings argue that ‘the space of the amateur opens out onto a range of interests invisible in the breathless flow of the professionally mediated, or state sponsored’ they seem to be offering the film makers the distinction of arbiters of what is ‘truly productive’ in the Poland of the period; for it is through their lenses that we are given access to these "invisible" activities, and through their lenses that they are validated; an abstraction of AKF culture from its conditions of production that forbids us from testing how productive or otherwise other uses of free time might have been in the eyes of the state, the artists and the audience.

.jpg) The ‘discursive territory’ of enthusiasm into which Cummings and Lewandowska insert the amateur film clubs seems to be part of a shift from the dominant understanding of amateur practices as taking place in a quaint social vacuum distinct from the professionalised world, to a recognition that the market is awakening to the potential of harnessing amateur energies. But behind this is another shift, a change in the demographic: what exactly is the social makeup of today's enthusiasts? The various representations of enthusiasm at work the post-industrial society avoid questions of class, preferring to view unofficial culture through a belief in an ‘aspirational’ populace. Take, for example, a recent contribution by the government thinktank Demos, declaring a Pro Am Revolution. While their argument correlates with Cummings and Lewandowska's representation of the amateur as ‘inverting the terms of work and leisure’, Demos go further in developing the model of a new class of enthusiasts ‘working to professional standards’, parallel to the hierarchies of the labour market. Their examples include amateur astronomers, gardeners and open source programmers; their contention is that the energies of these spare time producers should be harnessed to simultaneously enrich the economy, ‘improve social cohesion’ and undermine the power of large corporations. That the work time pursuits of the pro-am class pay off sufficiently well to facilitate their enthusiasms - the average pro–am is male, white and on an income of around £30,000 per year - and that their re–branding of the apparently socially embarrassing amateur along the lines of ‘professionalism’ implies a misrecognition of the learning process of amateurism in the first place - won't dent Demos' enthusiasm. What is evident as they begin to distinguish between types of amateurs is their operation of social distinction on practices based on levels of ‘intensity’ of engagement. The most interesting decision in Demos' scale is their situating of ‘Devotees, fans, dabblers and spectators’ at the bottom; a marking out of social territory disguised as a recognition of ‘commitment’. The acceptable ‘pro–ams’ are already generally in a privileged position, and it's easier then to produce a representation of a benign economy which inverts the terms of professionalised work - while in fact not only reproducing its systems of power, but bolstering them.

The ‘discursive territory’ of enthusiasm into which Cummings and Lewandowska insert the amateur film clubs seems to be part of a shift from the dominant understanding of amateur practices as taking place in a quaint social vacuum distinct from the professionalised world, to a recognition that the market is awakening to the potential of harnessing amateur energies. But behind this is another shift, a change in the demographic: what exactly is the social makeup of today's enthusiasts? The various representations of enthusiasm at work the post-industrial society avoid questions of class, preferring to view unofficial culture through a belief in an ‘aspirational’ populace. Take, for example, a recent contribution by the government thinktank Demos, declaring a Pro Am Revolution. While their argument correlates with Cummings and Lewandowska's representation of the amateur as ‘inverting the terms of work and leisure’, Demos go further in developing the model of a new class of enthusiasts ‘working to professional standards’, parallel to the hierarchies of the labour market. Their examples include amateur astronomers, gardeners and open source programmers; their contention is that the energies of these spare time producers should be harnessed to simultaneously enrich the economy, ‘improve social cohesion’ and undermine the power of large corporations. That the work time pursuits of the pro-am class pay off sufficiently well to facilitate their enthusiasms - the average pro–am is male, white and on an income of around £30,000 per year - and that their re–branding of the apparently socially embarrassing amateur along the lines of ‘professionalism’ implies a misrecognition of the learning process of amateurism in the first place - won't dent Demos' enthusiasm. What is evident as they begin to distinguish between types of amateurs is their operation of social distinction on practices based on levels of ‘intensity’ of engagement. The most interesting decision in Demos' scale is their situating of ‘Devotees, fans, dabblers and spectators’ at the bottom; a marking out of social territory disguised as a recognition of ‘commitment’. The acceptable ‘pro–ams’ are already generally in a privileged position, and it's easier then to produce a representation of a benign economy which inverts the terms of professionalised work - while in fact not only reproducing its systems of power, but bolstering them.

The concept of enthusiasm is a vague one: in truth, enthusiasm is employed very differently in different social spaces. The contention that it is today everywhere being ‘drained’ by becoming a resource for market forces, is perhaps inaccurate; rather, the work of enthusiasts is problematised by the turning out of knowledge distributed collectively, into atomised fields of financial competition. In the cultural sphere, where the energies of those enthusiasts who get left out goes, depends on their access to supportive structures. In taking the enthusiasts to the gallery, and onto the web with the aid of sponsorship, Cummings and Lewandowska imply that energies applied from ‘above’ are needed in tandem with the generation of ‘culture from below’. But their negotiation of public spaces in which to redistribute the work of the AKFs requires an openness about the social relationships that constitute unofficial producitvity. It's in the continuous recognition of, and alteration of, its own reproductive mechanisms that enthusiastic production might have a chance of undermining the market at a structural level; whether an economy based on belief can admit expressions of doubt is crucial to this project.

Notes

1. Sebastian Cichocki, Entuzjasci z Amatorskich Klubów Filmowych, Centrum Sztuki Wspolczesnej, Warsaw, 2004, pp. 82-3.

A full version of this text is available at http://wiki.caughtlearning.org/index.php/EnthusiasmWith thanks to Mattin & Leire

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com