King of Code

Interactivity. Social engagement. Cybernetics. Dialogue. Galleries-as-clubs. Sixties tower blocks. Smart clothing. Bandwidth Reality. Art on the Graphic User Interface… You could be forgiven for thinking these terms were stripped from yet another mailing list on art and technology hatched in the last five minutes. In fact, they all describe the work of artist Stephen Willats which has recently returned to prominence with a flurry of exhibits at Laure Genillard, the Whitechapel and Royal College of Art galleries. An interview by Josephine Berry & Pauline van Mourik Broekman.

Since the early 1960s, Willats has repurposed system-based theories in the social context - initiating multi-media art and design projects everywhere from suburban tennis clubs and public galleries to inner city housing estates. Fusing cybernetic models, an authorial death-wish and an enduring commitment to participatory politics, his work is poles apart from the media-friendly individualism of the yBa era. But, tempting as it is to attribute the renewed interest in his work to the rise of socially responsible product on the modern art taste-index, its context and implications are far wider: in a world in which horizontal communication structures are being hardwired on global proportions and social problems tend increasingly to beget technological solutions, his experiments with self-organising systems are instructive.

The scientific inspiration, apparent rationalism and political contradictions of Willat's work make its investigations in terms of classic net debates irresistible. So surrounded by the steady ticking of his studio's many clocks, the conversation between Willats and Mute opened up some of the following questions: To what extent can models lifted from the 'hard' sciences work their magic in the social sphere? Can socio-structural open-endedness be engineered? Are there forces controlling so-called 'open systems' and, if so, is resistance futile? Betraying a long love-hate relationship with art, his answeres turned on the mutable question of the cultural model and what it - in contrast to its scientific and technological equivalents - might achieve.

PB: Can we begin by talking about the Drian Gallery, where you worked in the late 50s? You have described this as a formative experience in terms of wanting to generate a different model of how art could work.

Well, it was a strange situation because I came to work in this art gallery from the world outside and it was an unimaginable leap of reality really. I found myself working in what was at that time a very avant-garde gallery environment and hadn’t come with any kind of lumber or been to art school or anything like that.

It quickly became apparent to me that no one ever went to the gallery except those who were already involved. It was a kind of capsule, really. This enabled me to have plenty of time to dream about different speculative models of how things could be. We have these moments of insight, and in my case I remember we were showing this artist called Agam — an Israeli constructivist whose work incorporated slats of colour that, as you moved across them, changed. They stimulated me to imagine that there could be quite another relationship of an artist to a work of art, because implicit in the work was the audience.

This led me on to set up a lot of diagrammatic models in ’58/’59 which postulated that instead of the audience coming along and finding objects of certainty — icons of emulation — in a sort of passive, almost awe inspired way, they came into what I described at the time as a ‘random variable’. It was task orientated; they were part of the creation of the work, of the meaning of the experience. The word I think I used at the time was ‘relativity’ — the relativity of perception and meaning. Another artist, Kosice, a Marxist Argentinian constructivist who made constructions with water which you could move and turn around, stimulated in me the idea of task orientation and tactile involvement.

JB: What about other kinds of post-studio art? Anything from Andy Warhol’s factory to Robert Smithson’s land art which tried, with very different means, to create something that exceeds that oppressive model of the artist, and which often used industrial technology to transform the mode of production to break with this older regime of meaning?

SW: London in the late 50s was quite provincial, and I remember quite clearly the first exhibition of American big painting at the American Embassy — these were devastating injections of culture from remote places and had a completely fundamental effect on many artists. Casting off the shackles of the ’50s was a rebellious experience and, indeed, there was this term, ‘Angry Young Man’, which seemed to sum up that general feeling. By the ’60s another kind of feeling had come about which was much more optimistic and which could see the possibility of another social realm altogether, another sort of ideological-political existence. An important aspect was the idea that nothing was the preserve of any one person. The idea that some scientist was involved in a discipline that he could keep hegemony over was anachronistic. People felt that they were in a free flow of information, and this was very fertile. Other people felt that they could be artists as well. The models we are talking about didn’t really become influential — in my opinion — until about ’63.

PB: Did you feel an affinity with these models when you encountered them?

SW: I found, and continue to find, myself at odds with most American political thought. I wasn’t overwhelmed by the vast resources available to American practice, and the kinds of cultural domination that it seemed to want and, in fact, got. I saw most of these models which were being represented in a highly verified and supported manner for what they were — a kind of determinism. They wanted emulation, what I was talking about was contextualism. I certainly fell out with artists — especially American ones — who thought that great art was universal. It was complete bullshit — all art is contextually dependent on social relations and agreement.

JB: So if there were any artists that you looked to at that time, who were they?

SW: Although people knew about my practice, it was seen as quite marginal. I found people like Gordon Pask and the people around Systems Research as well as Roy Ascott and his Ground Course really stimulating. In ’65 I stopped calling myself an artist and called myself a ‘conceptual designer’ with the specific purpose of terminating what I saw as the history of art and moving on. My idea was to infiltrate the infrastructure of society and deal with accepted behaviours and norms, and transform them. So I thought that what I could do with clothing, for instance, was to develop the idea of self-organising clothing — you could alter your relationship to other people in a process of exchange.

JB: So why did you go back to calling yourself an artist?

SW: Because nobody understood what I was talking about, basically (laughs). It was quite lonely.

JB: But, why work with art at all? Were you harnessing art as an agent of transformation — something that operates interstitially — between disciplines, for example — and non-instrumentally?

SW: Well, we wanted to take the fundamentals of what we felt an artist might be and relate this to what we thought was relevant to the social landscape. In ’65, for example, I was working at Ipswich with Roy Ascott on his course, and had a group of 20 students for a whole year for whom I had to develop my own program. The students came from Ipswich and Suffolk and hadn’t been, shall we say, conditioned in the history of art — the same way I hadn’t. We had the idea that we would develop collaborative practice, that the artist as sole author would not exist, and that all art would be social expression. The students operated as a collective and we decided we’d look at what would happen if we started from zero as artists: how would we develop a practice in relationship to the social situation? We had to look at basic ideas about audience, context, language, meaning, procedures of intervention, things like that. The group divided itself into four and each group developed a different strategy for a different audience group. The idea was that theory had to precede practice.

We took a housing estate on the outskirts of Ipswich and attempted to start from fundamentals — what language we were going to use. We’d have to start with their language, and we thought that the context should be their context. Instead of trying to vary their behaviour so that they came to the art gallery, why not place the work within their existing behaviours?

The students set up a means of retrieving this information from the audience group through a doorstep questionnaire looking at restricted language codes, restricted visual codes, speech and so on. Another group was looking at priorities and behaviours. Out of this they formulated a strategy that turned out to be a set of signposts for the neighbourhood telling people where things were.

PB: How was this project related to the cybernetic systems of feedback that you were interested in at the time? And notions like consensus, collaboration and competition that figured in computer-based research, for instance in war games?

SW: Well, it wasn’t just cybernetic models. It was a whole host of different disciplines which seemed to be parallel — information theory, communication theory, learning theory. They were interesting to me because they provided models which were conceptual but which also stimulated practice. I didn’t see that they were slavishly to be copied or that their goals were necessarily my goals, but they could be appropriated.

JB: Do you think that the methods you use to create this kind of communication and interaction are neutral? You often use that word in association with the idea that you want to create a ‘neutral interface’ or something which doesn’t overdetermine the process that then unfolds. But do you think that neutrality can be achieved in any method? You’re using, as you mentioned, information theory, cybernetics and so on, and those are coming out of a scientific practice which has been critiqued, at least latterly, as existing within the Enlightenment project, not a relativist project, as something that deals in empirical truths.

SW: No, I think that, certainly in the case of Ipswich, the outcome was sort of unknown at the beginning — it was open-ended. The construction of response is so dependent on experience. When I say that the thing is or isn’t neutral it really depends on intention. You could say that everything is neutral and nothing is neutral, depending on the position you wish to take. In a way, one means the same as the other philosophically; you can find yourself in a sort of circuit. But the intention was that it was an open frame, so in that sense it was neutral. When I say a system or a work is ‘neutral’ I actually mean that the outcome is not determined — that it doesn’t have a preferred view. But of course, the work itself is not neutral because it actually is its own message. When you engage with the work, it brings you into a kind of model of social relationships which are built around exchange and self-organisation — this is what I meant by being neutral. It isn’t meant in any kind of scientific manner — you’re getting confused between the way I’m operating as an artist, and the foundation of science and cybernetics.

PB: Can we go back to the agreement and consensus issue? When manifest on a larger scale, consensus is often associated with conservative or oppressive social paradigms. Are there glass ceilings for consensus acting productively, and how can we differentiate consensus from agreement here?

SW: I think you have to be careful about the way that you perceive these models operating. The notion of agreement implies within it a recognition of the complexity of the other person, whereas consensus doesn’t necessarily do that.

PB: Maybe we should look at this through an example of your work, say the project you initiated in Holland during 1993 Democratic Model where people tried to picture an ideal space?

SW: Well, this particular work was actually about the formation of society. I saw that the basic element, a sort of building block, within society was the small group. If you look at the dynamics within the small group you can infer larger structures — there is a tendency towards agreement; within a small group there’s the psychological possibility of the recognition of complexity within others — and a process of exchange.

We invited 32 people who had never met each other before and represented different roles in Dutch society to come together to this community room in Den Haag on Saturday morning. I didn’t know the people in advance — my friends assembled them. They were given a task, which was to externalise an implicit representation of themselves within an ideal space. By answering a question you externalise what is implicit. You encode it. I see the act of ordering something on a sheet of paper as reinforcing the process of externalisation to then feed it back to the self. It is a fundamental element of the creative process, which is why I’ve used the question so often in my work.

People spent half an hour or so drawing. At the end of it I blew a whistle and we threw a dice which paired people together. It seemed that two people were the basis of a cooperative structure. They were then given a larger piece of paper on which they had to try to make a joint space. They could do this in various ways, but it meant that they entered into a period of negotiation. At this point everything was fine. I threw a dice again and we had four people — two groups of two coming together.

If we look at conformity and compliance, there’s a tendency to want to reduce the complexity of your own role by compliance. But within a group of four people they were all really willing to open themselves up to a group, because that group was based on a sort of agreement, not consensus per se. This principle seemed OK to eight, but when it got to sixteen it became impossible. At that point, all kinds of complex situations came to the forefront. Some people sought to try to exert influence, which they hadn’t done before; some tried to organise the group; some people tried to break away from the group; different things started to happen. But the basic thing was that the group became unstable and upset with itself. And the reason they became upset with themselves was because they’d lost the feeling of society that they had before.

JB: But don’t you think that most radical social transformation does need to entail friction? I’m thinking about historical revolutions, and the moments in which transformation is most dramatically figured or realised — albeit only temporarily, I would also argue.

SW: Well, no I don’t agree. I’d say that you were involved in very radical transformations of the infrastructure of society and of cognition of the self, but that this has happened in a totally implicit way — evolution. It is interesting to note that in the late ’50s and early ’60s we had a situation in which the development of philosophical models had got beyond the technology. It led to a point in the late ’60s where science and art became so engaged with each other that science became political. People started to want to take responsibility for the ramifications of their own actions. So, by the 1980s we have a revolution taking place in the infrastructure without anybody knowing. The implications of what was being thought about in the late ’50s is really beginning to effect the world we live in now. But it’s not a revolution based on conflict — it’s come about through evolution in the infrastructure. And when we talk about technology it’s just a vehicle, a medium of exchange. It embodies different possibilities which you can open yourself up to.

JB: But the technological capacity of a society has huge ramifications in its culture and politics wouldn’t you say? McLuhan, for example, talks about how the book was indispensable to colonialism because it meant that an identical message could be duplicated infinitely, and could propagate national culture within a colonial setting.

PB: And if we take the technology of the Net, its multi-nodal, ‘interactive’ architecture is viewed as having a democratising potential. Has its development played out in as empowering or democratising a way as you’d once hoped, or do you see the flipside?

SW: Well, I think you mustn’t get confused between agreement and democracy. I mean, democratic processes aren’t necessarily based on agreement, they’re based on acquiescence. We go along with the majority verdict. Agreement is not that; agreement is about agreement.

PB: But, in the same way that you saw engineering culture build something evolutionarily, do you see a process of empowerment going on, now that that something is reaching a serious level of massification?

SW: Of the individual? No, I don’t think it’s got anywhere near that point. If you’re talking about the relationship of the person to the terminal and the representation of reality on the screen, it’s so encoded as to represent within itself a realm of meaning. I think the point is that the person is psychologically detached in referring that realm of meaning to the reality surrounding them. This means that people can make decisions on the interface that they can distance themselves from in reality, and that’s an extremely interesting effect. In my work in the 1970s I developed a thing called a Symbolic World. The idea here was to encode reality and create a psychological distance so the viewer could engage more freely in a kind of remodelling. It’s not dissimilar to the representation of reality through the screen.

PB: Could tell us a bit about your recent show at the Laure Genillard Gallery, ‘Macro to Micro’?

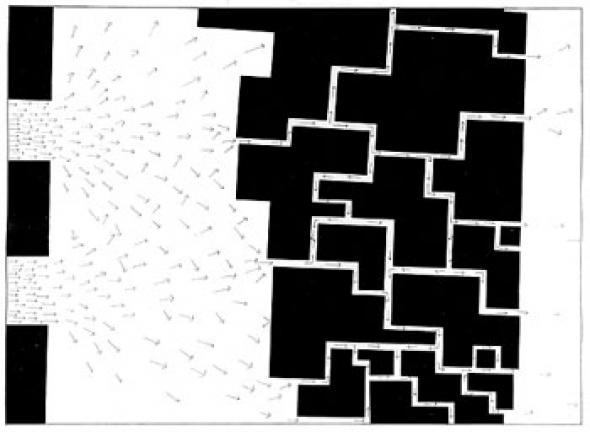

SW: Macro to Micro came out of a similar desire as the work in Ipswich from 1965. It seems necessary at the moment to set up models of practice that can be discussed. When I say discussed I mean in a way that is useful to the development of the way we think about art practice. I wanted to represent something about the complexity of the language of the contemporary world, and show that we construct order from what we almost randomly experience. This also comes into the idea of exchange and that of the work of art not being the product of any one person — whether we like it or not.

To start, I invited a group of actors who sort of specialised in disturbing normality. I told them my thinking turned around constructing four events, with one leading on to the other in time. Touring around West London, I had come across a shopping parade in Hayes with a very wide pavement which formed a natural kind of stage. The actors went along there and I left them to it really, saying I didn’t really want to know what they were going to do, but that they would be recorded. With the documentary group, we set up the idea of a concept frame — a purely artificial device to break down this multi-channelled picture of reality — and made various boxes, of which each person elected one to document. We used Super 8 cameras primarily, because they’re informal devices and provide an interesting way of recording reality.

The event itself was quite interesting: at 12.15 on a Saturday morning the documentary group crossed the road in Hayes and started filming all kinds of people, but they soon found out who the actors were and they followed them along these four events. Then there was a series of workshops over three months where the whole group edited the material collectively. The selected frames were then made into one still and printed up on a laser printer.

The ‘macro to micro’ in this sense is that there’s no ending and no beginning to it. It’s presented in the gallery space as a sort of multi-frame piece of information from which the viewer constructs their own order. So, it was meant to illustrate certain kinds of ideas about divestment, which I think is a very important model for the future of culture, and in a way is very ideological because it goes completely against the idea of the sole authorship and the elevation of the individual in terms of culture.

JB: Why did you decide to start using your name again in 1973? Was it just a practical means of survival?

SW: Yes, just practical. I felt that the idea had to dominate over the culture of the personality. And in that respect, I always felt that I was at completely opposite end of the practice from someone like Daniel Buren, whose name you’d hear and then each work was like a variation on the same thing. There were works developed by large numbers of people; it was just the idea of the work. So you had the Social Resource Project for Tennis Clubs, and that was it. Even with Metafilter, it’s only ‘Metafilter’. But when I started to try to intervene in the institutional process it wasn’t possible to maintain that. I always retained the name of the idea above the name of the artist. So instead of the name of the artist being big, it’s the idea that’s big — there’s no particular fetish about the authorship of the work.

JB: But it’s remembered as a Stephen Willats, or goes down in archives under Stephen Willats.

SW: So it might do, but that’s not the point. The point is the practical way in which it operated as a tool to work with, rather than as an emulative icon. So this is the difference in the paradigm of the work itself. These works were initiated by myself and that’s their actuality. They wouldn’t exist otherwise; you’re in a tautology there.

JB: From the way I observe your work I can’t see a totalistic political critique — say Marxist. Your work is definitely very left-wing, but it doesn’t employ a pre-existing political language. I’m interested in knowing whether your work advances something like a Grand Unifying Theory or whether it’s opposed to that idea

SW: Well, I don’t think it’s either. You can’t approach it that way. I think that the work is ideological in the way that it has an idea of the future. It proclaims a notion of what the future could be. And if you think of the future implied in the works from the early ’60s, for instance, we can say that the ramifications of these works have been taken up by what’s happening around us at the moment. The problem I had with a lot of the artists from the ’70s was that they became deterministic in their political outlook and this actually constrained them.

The reality of the situation we’re in is that it’s fluid, but that doesn’t mean to say that you lose track of your ideological position. I’m thinking with my work about the notion of transformation, the transformation of reality into self-organising structures which actually empower the notion of the individual. Now this is not a sort of dogma, but in my practice it’s a way of externalising my view into the reality of the culture around me. But I don’t want to take on the harness of any particular political dogma. Going back to your interest in engineering and cybernetics, one thing that was interesting about that period is the notion of being able to set up radical models of society without political dogma. I think that that was the interesting outcome of those debates. So I’ve always maintained a position of being independent of any particular dogma.

JB: Would you say that in comparison to other kinds of subcultural groups artists aspire to a greater reception, to making transformations far and beyond their own context. Unlike perhaps subcultural groups looking to exclude or operating on the basis of an exclusion from ‘normal society’.

SW: What I mean by ‘normal society’ is how society is projected by itself. So, there’s a sort of bandwidth of behaviour that is perceived as being normal. But we all know that there’s no such thing as normality. I want to address a bigger audience than just the primary people I work with. My motive for inviting the art world is to open up the nature of art practice. I think it’s very important that artists get beyond the idea of sole authorship.

JB: So in a way that’s your subcultural group — other artists.

SW: I’m in the business of trying to influence the cultural direction and transforming the future of culture. And certainly moving towards the idea of more complex and interactive structures within relationships which are ultimately self-organising. These are ideas which I think are very relevant to the current moment.

Josephine Berry & Pauline van Mourik Broekman <josie AT metamute.com><pauline AT metamute.com>

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com