Intellectuals with Street Cred?

What is radical research? Does it emanate from grass roots social movements, the universities, both, or neither? Melancholic Troglodytes review AK Press’s recent collection of ‘militant research’ with an illustrated tour following the book's line of enquiry from the ‘ivory tower to the barricades’

Professor, take off your bicycle glasses!I myself will expound those times and myself.

– Vladimir Mayakovsky

This collection of essays by self-described activists, academics, artists, anarchists, autonomist Marxists and situationists is an attempt to theorise the ‘social movement’. The topics under investigation cover a broad range from struggles within universities and factories to guerrilla gardening and anti-racist pedagogy. What unites them is the adoption of qualitative research methods influenced by postmodern currents within the social sciences.

The Melancholic Troglodytes are broadly sympathetic towards the book’s aim of creating new ways of researching the ‘anti-capitalist movement’. And since we are not deluded sectarians we readily confess that revolutionaries do not possess all the answers. Cross-fertilisation amongst various groups, including ‘academics’ and ‘intellectuals’, seems like a productive way of catalysing radical research. And for what it’s worth, and before we go any further, we would like to recommend this book to all those who consider themselves part of the anti-capitalist current. However, we do have certain reservations, both general and specific. The general criticisms will be discussed towards the end of the review. In the following paragraphs we wish to give due care and attention to specific contributions. Since the book consists of twenty texts we are naturally forced to be succinct in our assessment. As with any collection of texts there are strong pieces sandwiched between pedestrian accounts. Our critical comments will target the former and gallantly bypass the latter.

The introduction is written by Shukaitis and Graeber (pp. 11-34). It is an oddly muted call for unity amongst ‘marginal academics’. Instead of doing what a good introduction should do which is to signpost and contextualise forthcoming features, it concentrates on the often turbulent emergence of radical thought. In so doing it gets bogged down in a ‘battle of ideas’ narrative. Having made one or two sound points about the reactionary tendencies within sociology and American universities’ role in training staff for various global bureaucracies, the introduction commits a number of ahistorical errors. It brashly claims that ‘… universities were never meant to be places for intellectual creativity’ (p. 16). It rewrites the history of the proletarian movement by suggesting that early workers’ organisations were only concerned ‘with immediate economic issues’, whereas only recently have they become interested in cultural, artistic and symbolic phenomena! (p. 17). Finally, it assumes that after May ’68 activists carried on reading works immediately preceding May ’68 (e.g. Debord, Vaneigem, etc.) whilst academics continued to read works from immediately afterwards (e.g., Baudrillard, Foucault, Lyotard, etc). This may be a true generalisation of academics but it is not a fair assessment of activists who have always drawn on a much wider range of resources for comprehending the class struggle. We found this introductory ‘critique’ of universities lacking compared to sounder alternatives by Mustapha Khayati, David Harvie and George Caffentzis.

Things get worse before they get better. The next three contributions are low marks that lack the clarity and imagination of the rest of the book. Brian Holmes (pp. 39-43) believes he has discovered a ‘double dynamics’ in today’s geopolitics, ‘one that destroys what it constructs and dissolves what it unifies’. Holmes carelessly bandies about words like ‘neoliberalism’ as a synonym for capitalism. He lazily refers to ‘East European’ countries as ‘post-communist’ states and most disconcertingly suggests that the social sciences are ‘key’ and ‘compass’ for understanding the current global metamorphosis. Sociology will tell us who is in control and social psychology will graciously furnish us with insights ‘into the structures of wilful blindness and confused consent that uphold the reigning hegemony’ (p. 41). Ah dear boy, if only things were that simple!

The next article by Holtzman, Hughes and Van Meter emphasises how DIY activities can produce use value outside of capitalism (pp. 44-61). The examples of such activities range from zines that empower people to the punk movement in Britain which, we are assured, ‘provoked the greatest fear’ amongst the bourgeoisie! Surprisingly the three most outstanding theorists of the punk movement, Stewart Home and the Wise brothers are not referenced. Networked examples of DIY culture are also provided: we are subjected to a quite nauseating cheerleading of Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zones (TAZ), Reclaim the Streets/Critical Mass and Independent Media Centres. Not a single criticism of these networks is provided. Not one. It is as if Holtzman et al. are describing some perfect celestial temple! These networks are even presented as ‘non-ideologically-based’ and highly successful in resisting neoliberalism! Once again the most perceptive analysts of these ‘Leftist’ spaces (analysts such as Aufheben, The South East London Psychogeographic Newsletter, Re:Action, etc.) are given a wide berth.

Image (and all subsequent images): Melancholic Troglodytes

Next came Negri, and he had onLike Eldon, an ermined gown.

Antonio Negri, writing on ‘Logic and Theory of Inquiry’ (pp. 62-72), first reiterates his usual categorical mistake regarding ‘class’ and ‘multitude’, then updates the notion of ‘joint-research’ to ascertain the workers’ level of consciousness in these ‘postmodern’ times. And so far as he provides us with a definition of consciousness he seems to be merely updating the flawed notion of ‘consciousness as the reflection of being’ for our times. Rehashed postmodern Leninist gobbledygook is offered up as ‘new and original’. It seems for Negri strategy – if that is not too grandiose a term for his vision of ‘victory’ – has been reduced to a mathematical formula. If we cannot construct an alternative power to that of capitalism then we will ‘subtract from power’ through desertion and strikes!!! This is a false dichotomy. With all the arrogance of a General Custer, Negri commands that since we cannot wait ‘two or three hundred years for the decision of the multitude to become reality’, we must make power (Who is this ‘we’ that exists outside of the ‘multitude’?). However, in case ‘we’ are defeated then ‘we’ can choose ‘exodus’ as a strategic alternative. Hmm, crafty buggers, these petty bourgeois postmodern Leninists!

The next four texts are a distinct improvement. Colectivo Situaciones provide us with a reflexive synthesis of academic and non-academic militant research (pp. 79-93). They see this project as akin to ‘the activity of a communicative Wobbly, of a weaver of affective-linguistic territorialities’ (p. 83). For them ‘intelligence springs neither from erudition nor from cleverness, but rather from the capacity for involvement’ (p. 89). The article unfortunately takes us only so far, partly because of the group’s naïve faith in phenomenology and partly due to pretentious language. Regarding phenomenology, the text would have benefited from the astute criticisms of the American psychologist Carl Ratner and the British critical psychologist Ian Parker.[1]

Gavin Grindon’s work (pp. 94-107) is about reclaiming carnival for the social movement through a close re-reading of Bakhtin, Vaneigem, Bataille and (sadly also) Hakim Bey. Melancholic Troglodytes consider this an extremely useful approach and we look forward to reading longer pieces by Grindon. The article that appears in this collection discusses the famous Collège de Sociologie (1937-39) formed by George Bataille and Roger Caillois and lists some of its achievements as well as shortcomings.

Casas-Cortés and Cobarrubias reflect on ‘political cartography’ (pp. 112-126). They map contested geographies such as universities during Labour Day, pointing out their ‘role in flexible labor markets […] and defense contracts and recruiting’ (p. 113). They discuss the ‘picket-survey’, where ‘women armed with cameras, recorders, notebooks, and pens’ are dispersed throughout the city on strike days to hold conversation in the margins of the economy, ‘where the strike [makes] little sense’ (p. 116). They also criticise another qualitative research method known as drifting. This Situationist mode of inquiry is seen as appropriate for ‘a bourgeois male individual without commitments’ (p. 117). They then offer a project which could be understood as a feminist version of drifting, a kind of ‘dérive a la femme’ (p. 118). Melancholic Troglodytes find this notion of a feminist homosocial dérive a useful corrective to the Situationist original. However, the text is wrong in describing the latter as ‘bourgeois’. The problem with the original Situationist dérive was not that it was ‘bourgeois’ rather its male-centeredness and its confinement to only one plane of inquiry (the extra-psychological) at the expense of the inter- and intra-psychological dimensions of being. It is the flâneur who can be depicted as the uprooted bourgeois, not the situationist drifter – there is a difference! Finally, we felt this article could have done with some appropriate visual illustrations.

In ‘Autonomy, Recognition, Movement’, Angela Mitropoulos ‘retraces the history of the concept of autonomy from the early writings of Tronti to its more recent appearance in discussions of migration’ (p. 133). As with all her work it is an interesting contribution although probably not one of her strongest pieces. In updating Tronti, she has glossed over the flaws in Tronti’s over-hyped text ‘Lenin in England’ (1964). In asserting that globalisation was ‘imposed’ on capitalism by ‘a widespread refusal and flight of people’, Mitropoulos is viewing the proletariat as an independent variable characterised by ontological priority in a reductionist cause-and-effect relationship with capital. Furthermore, no evidence is offered. This is mere speculation, no more. She also claims that migration is a strategy. But what does that mean exactly? Is Mitropoulos imbuing the desperate act of flight from unstable regions of capitalism to relatively safer locales as a collective conscious anti-capitalist strategy? If so, she obviously feels under no obligation to demonstrate her thesis.

If Mitropoulos was trying to modernise Tronti, the next contributor, Jack Bratich, is on a mission to update Gramsci and in particular his notion of the organic intellectual (pp. 137-154). Bratich coins the unfortunate term 'embedded intellectual' as a more appropriate description for our era. He believes the ‘embedded intellectual is a figure not to be denounced, but reappropriated’ (p. 142). He proposes thinking of this embedded intellectual as a machinic intellectual (MI) who can come to subvert established think-tanks and their instrumentalist research ethos. His big idea for achieving all this seems to be for embedded intellectuals to somehow ‘disembed’ themselves and provide pro bono work for activist media groups (p. 149). The proposal ultimately fails to overcome the complex nature of proletarian epistemology and methodology. Nonetheless, this is a relatively thoughtful piece, worth debating.

Harry Halpin’s text is an amusing reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) and technology by an activist living in a tree-sit. It is good in so far as it criticises the incredibly naïve positions of John Zerzan, who lately seems to have become increasingly reactionary and superficial compared to his youth when his work still contained an element of refusal. However, the text betrays its own superficiality when waxing lyrical about Marx, Indymedia and AI. Halpin’s understanding of these issues is, frankly, not good enough. Furthermore, having used Wittgenstein and Lakoff tactically to query AI, Halpin’s critique of AI comes to a conveniently abrupt halt. Pity, since AI deserves a far more profound critical analysis.

We thoroughly enjoyed the next three contributions. Chan and Sharma’s text (pp. 180-188) is a deceptively simple piece about planting papaya seedlings on public land in Hawaii. This innocuous act has a number of consequences which ultimately leads them to denounce the concept of the public as ‘a corollary of nationalist ideologies of state power’ (p. 180). The private/public divide is for them two halves of a globally encompassing system of capitalist colonisation. An historical detour about the Diggers suggest that ‘during their time, it was fairly clear to people that their land was being stolen … [whereas] … today many of the things the Diggers fought against … are so hegemonic that to merely question them is to open yourself up to ridicule …’ (p. 184). We prefer the reader to discover the rest of this inventive text on their own. We are confident most would find it quite wonderful.

Kirsty Robertson (pp. 209-222) talks about knitting as both a metaphor for networking and as the literal activity of groups like the New York-based Activist Knitting Troupe who knit during demonstrations as a response to legislative bans on the wearing of scarves and masks (p. 210). Another group, Revolutionary Knitting Circle, uses a jigsaw-puzzle technique similar to Vygotskian collaborative problem-solving in their knitting projects (p. 211). These kinds of action are moving us away from (at times) pretentious, media-oriented, spectacular acts of symbolic sabotage and toward everyday actions. They create different and productive modes of communication amongst protesters. The text discusses some of the criticism levelled at knitting (some, for example, dismiss it as a conservative turn in American politics) but manages to come up with strong counter-arguments.

The subject of living on the streets is tackled from an autoethnographic perspective by BRE (pp. 223-241). This incidentally is one of the few contributions that explicitly talks about class, the rest of the authors either ignoring it altogether or pay it lip-service! Isn’t that amazing? BRE talks about the disgust generated by the media in the ‘citizen’ regarding street-dwellers and how this campaign paved the way for the New York police being given overtime to ‘harass, intimidate, and threaten poor people in the targeted areas of the city’ (p. 231). The text goes on to explain how ‘despite the images conjured by names like vagabond, drifter, or hobo, being homeless is an experience of bodily and spatial confinement’ (p. 238).

To my utter despair I have discovered, and discover every day anew, that there is in the masses no revolutionary idea or hope or possession.– M. Bakunin, http://en.thinkexist.com/quotes/mikhail_bakunin/3.html

The final two articles we are going to review are as offensive as the above quote from Bakunin. We like to describe them as theoretical manifestations of ‘yuppie-anarchism’. They leave a bitter taste in the mouth and smack of ignorance and arrogance in equal measure!

Uri Gordon (pp. 276-287) strikes us as very middle class, very atavistic and very suspect! Gordon’s catalogue of insulting remarks begins by defining anarchism in strictly European and North American terms (p. 276). He then goes on to describe Participatory Action Research in simplistic and apolitical terms (p. 277), ignoring how it was once a favourite of colonial powers because it made surveillance and control more effective. Gordon’s elitism shines through when he implies his fellow anarchists are not as erudite as he is (p. 277). He sees his task as ‘bringing the often conflicting views of activists to a conceptual level’ and clarifying, organising and articulating their ideas (p. 278). He is the activist/philosopher, you see, who is not just an ‘expert observer’ but also an ‘enabler’ and ‘facilitator’ (p. 282)! Gordon is building a career for himself by pretending that he is in possession of occult, underground knowledge about semi-secret radical groups. Maybe this is how he gains brownie points within academia and maybe there is something more sinister going on. We do not know. In either case, we find him deceitful and suspect.

The next example of yuppie-anarchism comes courtesy of CrimethInc Ex-Workers’ Collective (pp. 301-313). Ken Knabb has made some searching criticisms of this group but we don’t feel Ken goes far enough. Yes, obviously Ken is correct when he says CrimethInc have an embarrassingly naïve understanding of the Paris Commune, a rather ‘moralising simplisticness’ [sic], infantile views on hygiene (!) and a highly exaggerated view of themselves. But we feel there is something even more putrefied and rotten about this group. For one thing the text is peppered with religious terminology: ‘we need the second coming’; ‘worldwide apocalypse’; ‘the difference between a sympathiser and a revolutionary is mainly a matter of commitment’; ‘if the revolutionary is willing to live frugally’; ‘preaching revolutionary action’. This is made worse by a preponderance of macho, pretentious, even authoritarian language: ‘expropriating the white-collar world for revolutionary ends’; ‘we understood how important it was for the out-of-town black-bloc to be able to meet safely and get a good night’s sleep to be ready to riot in the morning’; ‘It would be more creative for anarchists to invade everyday jobs'; ‘if the state and corporations send infiltrators to our meetings, we should return the favour and place anarchist infiltrators in their offices’; ‘Why not get jobs as prison guards? … [or] … anarchist bankers’; ‘we are fighting a war’. Do we really need advice from CrimethInc on how to use a photocopier subversively (p. 309)? This is deeply patronising, stupid stuff. Yuppie-anarchists may be too navel-gazing to understand how insulting their preaching is but shouldn’t the experienced editors of the book (Shukaitis and Graeber) have known better?

As in an explosion, I would erupt with all the wonderful things I saw and understood in this world.– Boris Pasternak, http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/b/borispaste116666.html

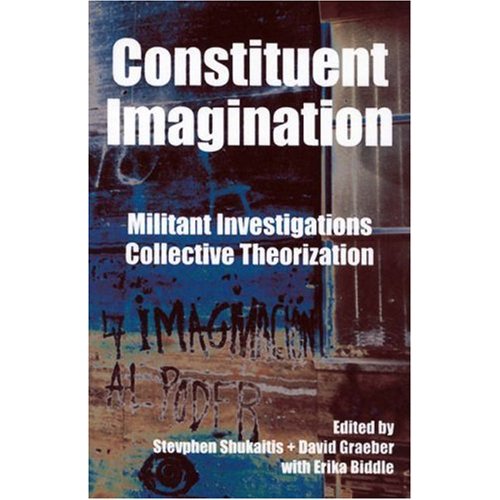

So, to summarise: Does Constituent Imagination help us see and understand the world? Does it help us erupt as in an explosion? Well… we wouldn’t go that far. It is certainly worth a read. A few of the articles are thought-provoking and informative. Sadly, the majority are too woolly to impress anyone who already understands the class struggle. One or two of the texts are offensively dire.

One major problem that recurs throughout is the fetishisation of qualitative methodology. Some of the writers seem to have only recently discovered methods such as Participation Action Research, ethnography and discourse analysis whilst feminism, critical sociology and critical psychology have been experimenting with these avenues of research for decades. All these methods can be enriching and productive in bringing out social tensions, subject positions, ideological dilemmas and power relations but they also possess inherent weaknesses. The authors do not seem to be aware of these shortcomings. It would be utterly counter-productive if this inclination toward qualitative research were to camouflage the speculative and impressionistic theorising historically associated with anarchism, situationism and (to a lesser extent) autonomist Marxism.

Another flaw is the naïve politics of most of the contributors. Writing from a by and large middle class (American-European) tradition there seems to be a dearth of nuanced observations of the class struggle. The exceptions to this rule only serve to foreground the problem. This naivety is most apparent when writers suggest a course of action or express their uncritical views on trade unions or their unconditional support for so-called horizontal networks. If this book is an attempt to create a rapprochement between anarchist activists and Autonomist Marxist scholars then our verdict would be this: The activist-oriented anarchists in this tome do not possess the street credibility needed to make Autonomist Marxism sexy and the latter is not represented in this work with sufficient originality and verve to imbue the Anarchists with intellectual capital!

Constituent Imagination is, therefore, an inconsistent but reasonably valiant attempt to theorise the social movement. Although devoid of any outstanding or pioneering ideas, we believe the book taken as a whole is sufficiently interesting to be worthy of study by anti-capitalist radicals.

Melancholic Troglodytes is a proletarian collective. We bring out an occasional journal of the same name about the class struggle. You can contact us at meltrogs1 AT hotmail.com

Info

Review of Constituent Imagination: Militant Investigations, Collective Theorization. (Edited by Stevphen Shukaitis, David Graeber and Erika Biddle), 2007, AK Press: Oakland, Edinburgh, West Virginia.

Footnotes

[1] The references we are thinking of are: Parker, I. (2007) Revolution in Psychology: Alienation to Emancipation. (London, Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto); and, Ratner, C. (1971) ‘Totalitarianism and Phenomenology, Telos, 7, Spring.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com