The Importance of Being Earnest, or Not

Two recent books focusing on the Situationist International, Expect Anything Fear Nothing and The Beach Beneath the Street, salvage the plurality of the group's activities, laying an emphasis on art, friendship and life praxis, rather than the usual theory and splits. Review by Christopher Collier

One of Guy Ernest Debord's major achievements was to know with both admirable poise and impeccable timing, the importance of a doctrinal earnestness, but likewise the value of a certain tactical expediency. Debord already? And its only the first paragraph. Are we not bored with Debord? As the Situationist International (SI) somewhat paradoxically maintained, boredom is counter-revolutionary, and yet it was boredom, they informed us, that was integral in the production of a contemporary revolutionary subjectivity. Boredom they said, produces a more generalised and generalisable alienation, emerging not from a proletariat alienated from the products of labour power, but from all those who would create life itself, alienated precisely by labour from their species-being, as playful, creative, collective subjectivities, as homo ludens. Perhaps then, the situationist slogan, if any, that we might take up today could be to 'live without dead time', to refuse the categorisations of work and play, not as the outsourced members of a multi-tasking cognitariat, rather as the creators of our own time, of our own situations, our own history. Two recent books on the situationist project, Expect Anything Fear Nothing and The Beach Beneath the Street, may constitute one of the best efforts yet at using the experimental praxis of the SI as a spark for the creation of our own time.

Image: Gordon Fazakerley in the yard of Drakabygget, Nash's farm and artist commune in Southern Sweden, 1961

These are two books that attempt to tell the relatively untold stories of the SI, leaving the commentaries on Debord and the spectacle aside and drawing our eyes towards the broad, dynamic, incongruous, 'real life' of the movement - a real life that was elsewhere. Perhaps, it could be argued, such self-consciously non-Debordist engagements with the SI simply represent the downward curve of a product life-cycle graph for an SI industry, mining some of their less well explored, less easily accessible terrain for additional material and squeezing some additional droplets of surplus value from under-exploited intellectual territories. Possibly, but perhaps it would instead be more generous to discover in them a well-judged reappraisal and a strategic liberation of the situationist project from the straitjacket of academic categorisations, opening it once more to praxis, as a collective venture whose fundamentally collective achievements may inform new syntheses in whatever tactician's toolboxes.

In light of this, both of these books must be cautiously welcomed for largely looking beyond the discourse of spectacle that has been so used and abused, including those polemic misreadings by certain well established and apparently all too wilfully ignorant schoolmasters in recent times. Spectacle was, for years, usually taken up as the central tenet of the situationist legacy, in no small part thanks to the postmodern turn exemplified by the likes of Baudrillard. Today, much of the spectacular critique of capitalism is simultaneously dismissed as overly simplistic or perhaps simply bad theory, and yet it is conversely taken as such self-evidently common knowledge that it is barely worth talking about. This is not to say there isn't real force in the notion of spectacle, and indeed Richard Gilman-Opalsky has recently gone some way towards rescuing the concept from its own spectacularisation as the straw man of art theory. Nevertheless, these books are a welcome acknowledgement that there is more to the situationists than merely spectacle.

As the misappropriations of the spectacle (read that which ever way you wish) teach us, passion for the SI is often the love that dare not speak its name, not least because it goes against all of their anti-heroic proclamations. A major achievement of these texts is daring to speak it. It is true that in recent years a number of influential voices from the the art-theory nexus have been quick to espouse anti-situationist credentials, and yet the fascination remains, even in the negative, as a provocation to the present. As McKenzie Wark reminds us, quoting the Letterist Gil Wolman: 'there is no negation that does not affirm itself elsewhere'. An uneasy flirtation with the SI runs through contemporary art and academic theory, somewhat embarrassed to admit an affinity, quick to fall back on cliché. For contemporary artists the situationist legacy can be an unspectacular bore, often misconstrued as some kind of proto-relational aesthetics. For academic high theorists it is often regarded as a superficial misdemeanour: misdirected youthful romanticism, glamour, drink, sex and rebellion, a 1960s idealism that is far too earnest for cynical times. The SI has become weighed down by cliché, but perhaps cliché is merely a boredom with truisms, and boredom is negation, its affirmation appears in unlikely places.

Expect Anything Fear Nothing is a notably earnest book, a book that feels like it gets close to the praxis of the SI, striping back the layers of mythology with matter-of-fact description, rigorous engagement with primary material and numerous contributions from ex-members. It de-heroicises the individuals of whom it speaks and if it historicises the SI it also demystifies, it somehow brings the original contingency of the group back into play. Such a group was not, one could conclude, particularly unique, singular, remote or messianic, but was rather ordinary, if still fascinating, radical whilst remaining generalisable. In opening up the historical discourse on the situationists towards their rather shamefully overlooked Scandinavian manifestation, such a book is an importantly pluralistic act; the texts with which Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen present us are a true potlatch of sources and interpretations. They de-spectacularise the SI on their own terms, opening their praxis onto contemporary situations, not prescriptively, but by offering some tentative analogies, opening up the texture of the movement to us with a far fuller richness, gifting to us translatable practices, not as generalised mythology but as detailed and often highly personal engagements.

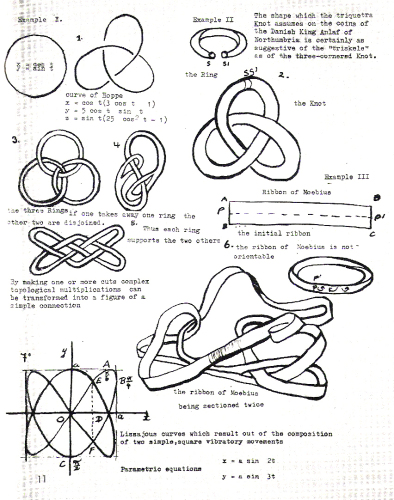

Image: Page from The Situationist Times, No.3, January 1963, p. 11

Rasmussen and Jakobsen present us with a book that appears to promise an important contribution to situationist discourse. Drawn from presentations made to a seminar at People's House, Copenhagen in March 2007, it appears as the first serious treatment of its kind in English of the situationist project in Scandinavia (although we should acknowledge perhaps Jakobson and Howard Slater's joint research project on the subject from a decade earlier)1. Broader and more pluralist than most engagements with the situationist movement, this collection of essays, transcripts and other materials attempts a fundamental rebalancing of the situationist legacy away from Debord. Whilst acknowledging his influence, it seeks to direct attention more towards a collective appraisal of the movement's activities, particularly focusing on the contributions of the those associated with the Scandinavian section, of Asger Jorn, Jørgen Nash, J.V. Martin, Jacqueline de Jong and Jens Jørgen Thorsen amongst others. Stories abound that the historical overlooking of the Scandinavians is down, in no small part, to Debord's rigid control of the SI's legacy and presentation. This is perhaps partially true but the caricature is unhelpful since it is no doubt also due to the geography of the cultural industries and academia, to linguistic barriers, to the relative inaccessibility of Jorn's writing and to the opportunistic and self-publicising tendencies of Nash, which arguably proved counter-productive. Superficially Debord perhaps has appeared as an earnest character, while Nash, the supposed forger and petty criminal, certainly has not. What emerges here however is far more complex, both were in fact more than open to the strategic interplay of earnestness and tactical presentation - and from theorists and practitioners of the spectacle what else should we expect?

At one stage this book bypasses that most fraught of points, the largely Debordian insistence that there could be no such thing as 'Situationism', by talking, perhaps more accurately, of Siuationisms. It is therefore the case that we find here engagements with many disparate and occasionally contradictory endeavours. There is discussion of the Drakabygget movement (roughly equal to the Second Situationist International); an artist commune run at Nash's farm in Southern Sweden, descriptions of which include disarmingly frank and detailed first-hand accounts from de Jong. We learn of the experimental filmography of the Drakabygget artists, and elsewhere several of the contributions deal in depth with the valuable transdisciplinary work of the Situationist Times across the fields of visual culture, science and mathematics, particularly through its engagements with topology. Jorn's fascination with topology is likewise brought out and convincingly analysed in another essay from Fabian Tompsett. Indeed, one of the main successes of this essay, and of the wider book, is to expose just what a vital role Jorn played, both intellectually and not least financially, not only in defining and developing the original situationist programme, but in many ways holding the International together and subsequently defining much of the course of the Second International as well. For its breadth and detail and for its plethora of new angles on situationist praxis, centred on, but not limited to the Scandinavian and artistic trajectories, this book lives up to the importance it initially promises. In its non-evasive willingness to apply this praxis to turbulent, contemporary political events, in the midst of which the conference took place, the book also proves that the situationist legacy is too important to be left solely to academia.

Throughout this collection, to adopt the title of one of its transcripts, persists 'a maxim of openness', not only opening up the legacy of the situationists historically, but opening itself up to the present, for détournement and for praxis. This is a facet that Rasmussen's detailed analysis of the 1963 RSG-6 exhibition in Odense illustrates through the way in which he challenges and reappraises the accepted, polemic narrative of the SI's 1962 split between 'artists' and 'politicos', analogously perhaps drawing attention to Michèle Bernstein's rewriting of history in her work Victories of the Proletariat. It is worth noting that the methods utilised by the RSG-6 activists which the SI chose to publicly champion - the leaking of secret military information and mass 'denial of service' attacks (by telephone in those days, rather than internet) - demonstrate the situationists' keen sense of tactical awareness, particularly in the field of communications, and indeed as we have seen over recent times, such tactics remain relevant and useful in today's struggles.

Expect Anything Fear Nothing is a serious and thoughtful book, it could have easily fallen into a pointless polemic against Debord, and indeed I would argue that its least successful contribution comes in the form of Stewart Home's return to his apparent vendetta against what he has termed the Specto-situationists. Whilst he offers some valuable context of the SI's place in a broader ecology of counter-cultural and pseudo-criminal gang culture in Britain and the US in particular, he advances little on the provocative characterisations made in his earlier work on the situationists in The Assault on Culture and What is Situationism?: A Reader.

Rasmussen and Jakobsen's collection thankfully does not take the route of turning the political infighting of the situationists into some kind of spectacular soap-opera substitution for the substance of their practical and theoretical contributions. It neither diminishes nor over-dramatises these internal conflicts, rather it places them firmly where they belong, as an often trivial, occasionally comedic diversion amongst serious people.

If this book makes a broad argument it is the argument for the amateur, for the non-academic, for low theory. It contains all of the passion and seriousness of a dedicated amateur historian, unpretentious yet rigorous, perceptive and unsentimental. Without attempting a total sweep of history, without the urge to present a unified picture, this work remains open and inquiring and ends up yielding so much more practical insight that the mythologising tendencies it no doubt would have succumbed to should it have attempted a more 'objective' historical narrative. It is telling that such a book should ultimately emerge from the legacy of the Copenhagen Free University, a project that offered a glimpse at some of the many aspects that a broadly 'situationist' praxis might take on within a relatively contemporary context. At the heart of the book lies one-time SI member Hardy Strid's text Everyone Can Be A Situationist, a short and frank statement serving to open the situationist project beyond organisational structures, beyond hierarchy, even beyond the intricacies of terminology and outwards, essentially as a spur to creative discovery in the politico-aesthetic field. Such a text is perhaps then an apt sentiment for the book's editors to orientate the wider collection of materials around, for it is a sentiment echoed strongly across the book's disparate contributions.

Image: Dagbladet Fyn article about a dispute between J.V. Martin and Tom Lindhardt: 'Also Ideological Dispute in Odense'

If Expect Anything Fear Nothing could be characterised as earnest, McKenzie Wark's offering on the other hand could perhaps be labelled strategic and performative. The Beach Beneath the Street self-consciously and paradoxically strives to defend the continuing value of the SI as laying outside of, and resistant to, commodification or academic subsumption; an argument valid and well made, and yet it takes an academic in a book that is an especially attractive example of the commodity form to make this point. A sexy book for a sexy movement perhaps - after all the SI never shied away from high production values - but this is not the only unease that we as readers and all those that write on the SI habitually grapple with. It has become a cliché that books on the SI begin with apologies, usually for the impending contradiction between the tactics espoused, occasionally heroicised, and the implications inherent in the act of publishing a book about them. This is the curse of recuperation, just one of Debord's delicious tactical jokes bequeathed to subsequent generations of hero-worshippers and detractors alike.

Ostensibly a very different book from Expect Anything Fear Nothing, Wark's prose is exuberant, laced in true SI style with hundreds of détourned soundbites and one-liners, not just from the situationists but also from Marx and many more mined from the mountains of subsequent critical theory.

Just as arguably there are many situationisms, this is perhaps many books. As an introduction to the SI it is a novelistic, anecdotal roller-coaster through the European avant garde and radical bohemia. To the non-specialist, vaguely familiar with the SI, the book is an immensely valuable opening onto the bit parts that defined the whole political drama that was the International, playing up the collective effort, playing down the heroic (and yet conversely heroicising through style: structuring the narrative primarily by personage as opposed to concept). To the specialist or the 'pro-situ' (categories the SI would have denounced), the book is a thousand speculative insights, within which those under the influence of the SI might find an affirmation of the analyses that they continue to apply to numerous contemporary situations.

Throughout the text Wark deftly weaves a sustained engagement with the themes of situation, potlatch, détournement and dérive across an array of semi-biographical accounts of the main actors. In doing so he elegantly rebuts those mainstream, somewhat apolitical treatments of dérive and psychogeography from the likes of Rebecca Solnit, Merlin Coverley and Simon Sadler, whilst locating notions of situation and potlatch within their extended existential and anthropological discourses respectively. In this Wark achieves something not to be under-estimated, producing a coherent and yet inherently pluralist work on the legacy of the SI and particularly their less well-known predecessors the Letterist International. Indeed, it is worth noting that in his relative concentration on Letterist and early SI concerns, Wark appears somewhat dismissive of the group's latter stages, the major texts of Debord and Vaneigem (who is conspicuously absent throughout) barely get a look in. The lengthy engagement with letterism and its context is welcome and Wark re-articulates its key tactics of dérive and psychogeography, not merely as quaint precursors to a more sophisticated critique of consumer capitalism and functionalist urbanism (often identified as belonging to the theories of spectacle and the architectural endeavours of unitary urbanism), but as important practices in their own right, deeply integrated into a unified critique of contemporary ontology via the notion of the construction of situations.

He ranges widely, devoting some much appreciated discussion to the sexual politics at play in the bohemian love stories of Michèle Bernstein's novels and the ambitious and prescient visual essays of the Jacqueline de Jong edited Situationist Times. He acknowledges the pivotal role of Asger Jorn and his original and under-explored ideas on creativity, arising in a pseudo-Marxist critique of value but on the basis of quality and difference, rather than the homogenising critique of abstract labour. Drawing upon Bataille's notion of surplus, Wark contrasts and compares it not only with Jorn's concept of value production, but perceptively with the utopian, ludic cities of Chtcheglov and what he less convincingly paints as the non-utopian cybernetic détournements of urban form and mechanised production to be found in the vision of Constant's obsessive architectural project New Babylon. He addresses the experimental form of Alexander Trocchi's Project Sigma, always drawing acute analogies with the contemporary era, as in this case by relating it to the field of new media technologies. Not the least of his achievements is to undertake a valuable (if inevitably brief) contextualisation and reappraisal of Henri Lefebvre's important relation to the situationist project, but concentrating on the notion of everyday life perhaps at the expense of the equally fruitful avenue of Lefebvre's work on space.

This is a beautifully written, exciting and broad study, one that may perhaps become a definitive introduction to the SI for many, defining them more comprehensively and more collectively than most others who have gone before. Wark's engagements here are not hugely in-depth, theoretically at least, but given the book's range this is more than understandable and indeed forgiveable, as although not an especially radical book, it is by no means superficial or uncritical either and as a strategic intervention it might just succeed. Such is its allure as a general overview to many of the multidimensional strands of the SI, that it might do valuable work in drawing readers towards more radical and more in-depth personal engagements with the material that it points up: to learn from the tactics and even the stylistics of such a movement as a tool for contemporary, self-directed, self-organised analysis. In this sense it triumphs, not in prescribing the applications of a situationist praxis in the 21st century, but doing all it can to open the possibility that such applications might occur. It entices the reader to translate the material into their everyday life, to select from the array of weaponry laid out before them and to détourn the gifts of the SI potlatch, represented here in more accessible and dynamic form, into the tools of a new, radical, even revolutionary praxis.

Image: Jacqueline de Jong, Attila Kotányi, Raoul Vaneigem and Jørgen Nash at the conference in Gothenburg, 1961

These studies emerge into a climate in which situationist-tinged ideas seem particularly opportune, more so perhaps than for a generation. Around us unfolds a backlash against neoliberal austerity, urban segregation, accelerated privatisation and privation of resources In advanced capitalist states we find a growing poverty of everyday life, intensified by an increasingly unstable trend towards enforced precarity and the cracking of vacuous official narratives of both individual aspiration and popular entertainment. Bread is too expensive and circuses are wearing thin.

We see the legacy of the SI manifested in the growing deployment of direct action tactics and the spatial politics of occupation increasingly adopted by anti-austerity and education activists alike. In illuminating the antecedents of the current vogue for 'flashmob' protest (often caricatured in lazy journalistic shorthand as 'situationist') in the aesthetico-political stunts of Nash and others, perhaps these texts also offer a potential reorientation of such tactics away from their frequently moralising tendency to merely make reformist demands for a more 'ethical' capitalism. As such, these powerful re-articulations of the situationist legacy might offer the chance to both contextualise and renew the movement's achievements, not for interpretation, but for praxis.

The continuing value (if perhaps ultimate inadequacy) of situationist influenced tactics within contemporary struggles has become increasingly evident. Such value is evinced in a radicalism that is not co-opted by mere resistance; a certain playful exuberance, of adventure and of low theory, the détournement of the mass media and the importance of autonomous working class action, all of these are trajectories that the books seek to open up. Such a legacy is not that of Debord, any more than that of Nash, or Jorn, or Lefebvre, or Viénet or any of them - it is a collective legacy, a potlatch, a tactical gift bequeathed collectively to the present. Both Wark's text and Rasmussen and Jakobsen's collection are intensely worthy of being read in their own right, however to read them together is to complement the strengths of each. To do so is to bring both the earnest and strategic into play once more, in our consideration of the important situations that these writers skilfully depict, and the still more important situations that we continue to create.

Debord once spoke of light-heartedly being at war with the whole world. These texts rejoin the battle, but perhaps also with heavy weaponry: a tactical weaponry which not unlike Bernstein's Victories of the Proletariat, makes a call to redefine the struggles of the past, and in so doing, to influence the struggles of the present.

Christopher Collier <christophercollier7 AT gmail.com> is an artist, writer and postgraduate student, currently conducting research into the notion of place within the SI corpus and its relation to both contemporary social movements and aesthetic practices. He is a founding member of The University for Strategic Optimism, http://universityforstrategicoptimism.wordpress.com/, and the Dérivelab collective

Info

Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Jakob Jakobsen (Eds.), Expect Anything Fear Nothing: The Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere, Nebula in association with Autonomedia, 2011

McKenzie Wark, The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International, Verso, 2011

Footnote

1The joint research project by Howard Slater & Jakob Jakobsen conducted in various Copenhagen archives culminated in a website of translated materials (http://www.infopool.org.uk/situpool.htm), a discussion event in London and Slater's important 2001 essay Divided We Stand, reviewing the Scandinavian situationists, that was published as the pamphlet Infopool #4.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com