Humiliation and Hope: Alfredo Jaar and Simon Critchley in Conversation

Amidst the last months' mediated stream of social and natural Events – from the revolts of the Arab world to the naturo-nuclear disaster in Japan – artist Alfredo Jaar and philosopher Simon Critchley discuss their responses to this dense spectacle of violence, destruction and hope. This is the first of a short series of dialogues convened and introduced by David Morris

I heard Simon Critchley speak recently about heretical groups of the 17th century and how they connect to the contemporary avant-garde (a theme of his upcoming book). His talk made me think of the work of Alfred Jaar which probes the limits of art as a political activity, with an eye on news media and representation; the majority of his practice is dedicated to activity outside the traditional ‘art world’ and entails public interventions, workshops and teaching.

I contacted them in early January to suggest a conversation about art and philosophy – they were both enthusiastic, but busy. By the time we got started, events across the globe seemed like a better place to begin. These are the circumstances in which the conversation began, and we will update regularly as it goes along.

Simon Critchley is Chair and Professor of Philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York. He has written numerous books, the latest of which, The Faith of the Faithless, will be published later this year. Alfredo Jaar is a Chilean-born artist, architect and film-maker, living in New York. He has exhibited widely around the world, and has upcoming shows in Seville, Sharjah, Amsterdam, Bern, and Kiasma.

David Morris, 8 March 2011

Without meaning to curtail the small talk, a question occurs to me of some significance, which I'd like to begin with - both of your work has some resonance with respect to recent news from the Middle East and North Africa. Can I ask for your thoughts on the ongoing uprisings?

Alfredo Jaar, 14 March 2011

As I started writing these lines about the Middle East, I checked the most recent news. I felt I needed to be as up to date as possible. I learned from The Guardian that ‘Gaddafi forces rout rebels in eastern Libya: Rebels driven out of town of Brega under heavy bombardment as pro-regime forces advance towards Benghazi'. The New York Times informs me that ‘Pro-Qaddafi Forces Press Rebels East and West of Tripoli'. But I also learn that further east ‘Afghanistan suicide attack kills dozens as Taliban claims responsibility for third attack in a month in formerly peaceful Kunduz province'. I observe that these news stories are relegated to the second tier everywhere as the tragedy in Japan dominates the news. I am in shock: ‘Fears Spread Over Nuclear Crisis; Quake Death Toll in Japan Soars; Radioactive Releases Could Last Months; New Blast Reported'. A first domino effect is already palpable: The Times reports that the ‘U.S. Nuclear Industry Faces New Uncertainty: A fragile bipartisan consensus on nuclear power's promise for the United States may have dissolved'. Good news in the middle of disaster, I thought.

Image:An inside job? The financial crisis congressional hearings, September 2009

As I do every Monday, I check Paul Krugman's column. Today he comments on 'Another Inside Job', alluding to the documentary Inside Job that recently won an Oscar. He writes that 'What the film didn't point out, however, is that the financial crisis has spawned a whole new set of abuses, many of them illegal as well as immoral. And leading political figures are, at long last, showing some outrage. Unfortunately, this outrage is directed, not at banking abuses, but at those trying to hold banks accountable for these abuses.' As we all know, not a single executive responsible for the worst financial crisis the world has ever experienced has faced justice. I also check the most recent news on Bradley Manning, the Army private accused of turning hundreds of thousands of secret US documents over to WikiLeaks. I have been following his case for a while. The 23 year-old soldier has been in a detention cell in Virginia. His lawyer has denounced the inhuman, illegal conditions in which he is detained. According to him, Manning is kept in 'conditions tantamount to solitary confinement and has been forced to sleep naked and stand at attention while naked. He is reportedly on suicide watch.' Thankfully, late last week, State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley reacted publicly: 'I spent 26 years in the Air Force. What is happening to Manning is ridiculous, counterproductive and stupid, and I don't know why the Department of Defense is doing it.' Crowley was forced to resign immediately. Sadly but not surprisingly, Barack Obama, at his Friday press conference acknowledged the situation but dismissed it.

In the face of such chaos, I am reminded of Mao Tse-Tung's words: 'The situation is excellent; there is great chaos under heaven'.

What can we do when the world is in such a state? What can we do out of this information that most of us would rather ignore? Can art make a difference? Even a small one? It can, of course, but the complexity of it all seems overwhelming and the challenge enormous. I am very tempted to go to bed right now with Adrienne Rich's new book. It is titled Tonight No Poetry Will Serve.

I strongly hope that the autocratic regimes in Libya, Bahrain and Yemen will fall soon, and all the other ones in the region too. There is an observable, undeniable, unstoppable drive for freedom in the Arab world and we should be filled with joy. I can't help myself thinking about how it all started: Mohamed Bouazizi was an unemployed student in Tunisia who was surviving selling vegetables in the small town of Sidi Bouzid's local market, without a license. But the authorities caught him and requested a bribe. He refused. In the fight that ensued, one of the inspectors, a woman, slapped him on the face and spat on him. She also insulted his father. 'He was so shocked and utterly humiliated. It was so shameful and, to him, a loss of dignity', her mother said to a reporter. When he went to the police station to seek justice, he was thrown out. Feeling humiliated and desperate, he publicly set himself on fire in front of the government building. He died of his burns 18 days later, on 4 January, 2011. Twenty-four hours later, the revolution started in Tunisia.

Image: Tunisian Protests

The world can still hear that slap on the face of Mohamed, and I hope that sound will continue to reverberate in every region of our planet. One day we will erect a monument to this young man. 'Life is more important than art', wrote James Baldwin, 'that is why art is so important.'

Simon Critchley, 15 March 2011

That's right, Alfredo. One act of humiliation, one shameless act initiated whatever it is that we call what's happening in North Africa and across the Middle East. I don't know whether Revolution is the right word. For me, the word is suspect as the first historical event that was described as a revolution was the Glorious Revolution in England in 1688, which was hardly glorious. Perhaps revolution is best reserved for the movement of the planets and the advertisement of automobiles and other technological wonders. What is taking place is a massive structural political dislocation. I want to come back to that act of humiliation, the routine policing of a slap and a spit in the face.

But first a moment's pause. I have been watching events unfold in the past months with an obsessive focus that has found me getting up at all times of the night and watching Al Jazeera in English and anything else I could find. Part of this was caused by the fact that whatever we call these ‘events' – and it surely not for us to try and name them – they began in Tunisia, which is a country I visited repeatedly from about 1998 to 2003 and tried to learn about. I couldn't have imagined a more perfect police state, a kind of East Germany on the Mediterranean. Of course, I understood nothing of this at first, but eventually I was told by my host during my first trip in a hushed voice late at night how many secret policemen and informants had been at the conference I was attending in Tunis. I have lots of other colourful anecdotes, which I shall spare you, but the point is that Tunisia seemed to me to be the last place on earth where some process such as we have witnessed in the last months might begin. I remember speaking to the US Ambassador to Tunisia at a nauseatingly dull reception for visiting academics in 2000, and asking for his opinion of the regime of Ben Ali. He described it as a 'well-run democracy'. Who says that Americans have no sense of irony?

Image: #revolution

I am so happy that events in Tunisia took the form that they did and that they unleashed the complex series of struggles that we are witnessing now, whatever the outcome. Whatever the outcome. But I didn't want to write anything about it. Mainly because my joy is mixed with genuine fear for what might happen and indeed what is happening today in Libya, Bahrain and elsewhere. But by addressing you, Alfredo, who I don't know personally, but whom I admire, I feel I can loosen my tongue a little by not really speaking directly.

I knew a Tunisian PhD student studying in England some 10 years ago. I even examined her PhD dissertation. She was brilliant and precocious. Her name is Hager Weslati. I was idling on Facebook a couple of months back and saw a comment from her in response to a piece on Tunisia by a prominent Western intellectual. She said something to the effect of ‘God, can't you people wait. Haven't you got any respect?' I took her point to heart. It seems to me that it is a time to listen and learn and not look for confirmations of one's theoretical categories in political actuality, which strikes me as an essentially masturbatory gesture.

And Alfredo, you are right, the world is a deafening, violent place dominated by an ever-enlarging incoherence of information and the constant presence of war. Today, 14 March – my mother's 80th birthday – Libya slips from the headlines and the vast, stupid, peanut crunching voyeurism that we call the news rightly lurches to the North-East coast of Japan. They have better images, I guess. Will this complex spectacle of resistance and transformation all slip from the headlines in a few weeks as we slide into the oblivion of the next crisis? I hope not, though I am fearful, deeply fearful.

The Greeks had a way with words, didn't they? There's an old expression, ‘Shame lies on the eyelids'. It describes the downward cast glance of the person who feels shame. Oedipus joins the ranks of the shameful through his act of self-blinding at the end of Oedipus Tyrant. The tyrant (tyrannos) has no shame and sees and hears nothing but that which provides an echo of a delusive self-knowledge. Thus, Qaddafi, in those agonisingly long speeches from a couple of weeks back, hears nothing from his people and sees only the image of himself reflected back in his Ray-Ban sunglasses. When Oedipus passes from delusive self-knowledge to the truth of himself, he puts out his eyes. He does not want to see, he does not deserve to see, for shame.

Qaddafi feels no shame, Mubarak feels no shame, and for God's sake Berlusconi feels no shame. Mohamed Bouazizi felt shame at the way he was shamelessly treated and took his life in an act of destructive courage.

What will happen? I don't know. What would I like to see happen? I have one or two ideas, but perhaps I'll reserve them for a later reply.

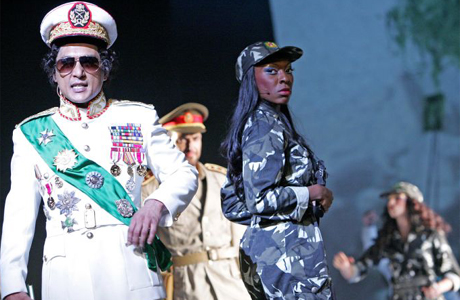

Image: English National Opera's Gaddafi

What can art do in such circumstances? I completely agree with what you say, Alfredo, but let me add something. I'm obsessed with tragedy at the moment as I'm teaching a course with Judith Butler on the topic and it's great fun, in a rather macabre way. Anyhow, I was reading Anne Carson's introduction to her translation of Aeschylus' Agamemnon this evening, and she finds this quote from Francis Bacon when he reflects on the purported violence of his painting. Bacon says, 'When talking about the violence of paint, it's nothing to do with the violence of war. It's to do with an attempt to remake the violence of reality.' He goes on, 'We nearly always live through screens – a screened existence. And I sometimes think, when people say my work looks violent, that I have been able to clear away one or two of the veils or screens.'

Existence seems to me ever-more screened and distanced, a shallow shadow world whose ideological patina is an empty empathy. None of us is free of this. Maybe art, in its essential violence, can tear away one or two of these screens. Maybe then we'd begin to see. Because the whole problem turns around what is seen and not seen. We think we see what happens ‘there' and make pronouncements about ‘them'. But we do not see as we are seen because we are wrapped in a screen. There are tyrants here too. Art might unwrap us a little through its violence.

David Morris <david.morris AT network.rca.ac.uk> is a writer and philosophy tutor based in London

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com