How do we move beyond ‘I’m being watched’?

Surveying Surveillance, part of the This is Not a Gateway Festival 2008 (TINAG), invited artists, academics and directors of security companies to discuss CCTV. A participant reports

‘Surveying Surveillance’ was a day-long event aiming to raise debate on the omnipresence of CCTV systems in the UK and took place at Vortex Bar in Dalston. Even though the morning workshop was scheduled for 11am on a rainy Sunday morning, Alex Haw surprisingly found himself speaking to more than a dozen people.

The TINAG festival is organised by a group of the same name whose main concern is to create platforms of debate where issues related to the city are addressed. Alex Haw, an architect, teacher, writer and video-maker, was invited to lead the event at Vortex. He had scheduled for the morning the task of going on a mapping mission around Dalston, locating CCTV systems and interrogating their operators. However, the idea was eventually frustrated due to weather conditions and the preliminary introduction was extended into an informal chat that functioned as a preparation for the more formal talks scheduled for the afternoon. Under the ledge, someone told me, the conversation led to the issue of surveillance beyond CCTV.

The issue of CCTV tends to receive a great deal of attention in debates about surveillance, but this is a matter that goes far beyond these systems. Surveillance cameras might be one of the most obvious methods, but not the only one. Individuals and their activities can be made visible in more efficient ways than by means of image capture. In fact, almost daily one is required to make herself visible scattering her body throughout endless databases. Personal information is the price of a great deal of the services we require. It is service in exchange for data.

Image: Anna Barriball, ‘I think I’m being watched’

The convergence between the welfare state and the surveillance state is illustrative of this trend – the UK being its paradigmatic example. Whether it be health care, street safety, jobseekers allowance, housing benefits, or maternity aid, all social services come at the price of putting oneself under rigorous scrutiny. And in the private sector things work in a similar fashion, with Email, FaceBook, fidelity cards, internet accounts for energy provision, phone, TV, and so on. The rule is: Feel free to do, as long as what you do is made visible.

Those that choose or are forced to remain invisible – either for political reasons or simply as a matter of survival – see their mobility extremely restricted. Mobility goes hand in hand with traceability. You can move as long as you leave traces. Societies of control, it has been widely argued after Foucault and Deleuze, are not about enclosure, but about tracked fluidity. Check points are found at every step and those registered are quickly granted access. Technologies evolve to make the check point procedure smoother: wave-on, swipe your card, feed our database and continue the journey. Check points are becoming increasingly invisible, while they work to make our movements ever more visible.

Even CCTV systems work in collaboration with databases: traffic control cameras register vehicle plates, others use facial recognition technology, sometimes software for the detection of movement patterns is implemented, and other times footage is kept as a police record. These and other issues were on the agenda for the afternoon session.

The first speaker was Peter Fry, director of the CCTV User Group. He gave a spectacular presentation on how effective CCTV systems have been, in some cases helping police to arrest criminals. Aided by some thrilling clips of real footage, he tried to persuade a rather sceptical audience of the benefits of CCTV, highlighting exceptional cases in which it has been effective. Being the director of the CCTV User Group, he was particularly concerned with showing how important the role of the operator is. The story goes as follows.

Someone is getting cash out from an ATM, with a guy prowling around his back. The operator is suspicious and zooms in. He is right. The guy at the cash point gets smashed in his head and the aggressor takes the money and runs. The operator follows him with the camera. Once the thief moves out of reach, another camera continues the pursuit. The CCTV operator contacts the police and both cooperate until we eventually witness the arrest. Brilliant!

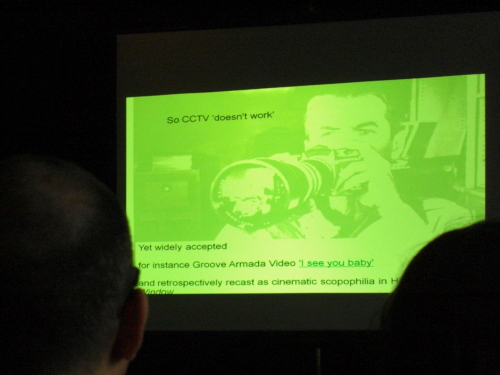

However, Peter Fry’s minute of fame, if he ever had it, was over as soon as the following speaker, Nik Goombridge, showed the Home Office report on the impact of CCTV in crime reduction. Goombridge is a lecturer in criminology and media at St. Mary’s College and has worked for the Home Office in the department of crime reduction. The paper he showed us concludes that there is no evidence that CCTV systems in the UK have had any impact on the reduction of crime. Cases like the one Peter Fry used to back up his argument are the exception, and yet they continue to inform the discourse of those in favour of surveillance. Goombridge’s presentation wasn’t particularly revealing but managed to address two of the key issues that led the debate later on: first, the question of effectiveness, and second the theme of artistic responses to surveillance.

By bringing up the report from the Home Office, Goombridge questioned the capacity of CCTV systems to reduce crime. However, Peter Fry argued later that if reports are claiming that CCTV systems are ineffective, it is because many of them are being misused.

Image: Slide of the presentation at Vortex, 26 October 2008

However, the discussion seemed to take a more fertile direction when someone raised his hand to say that the debate should not be centred on effectiveness. ‘CCTV is not about reducing crime; it is about reducing the fear of crime.’ And, I would add, it is a tool for the mass modulation of mood and is about producing the fear of transgression. Cameras are both the symptoms of a fear infection and one of its causes: they tell us how widespread is the paranoia of danger and they keep feeding it. The process is highly contagious and none of us are immune, no matter how critically we think about it. Surveillance systems are a plague that feed the fictions of danger often used as a tool of control. Perhaps it is where CCTV systems encounter the fictions around them that the most interesting forms of resistance can be articulated. Unfortunately, although I found the comment very inspiring, it didn’t seem to inspire anybody else and the conversation continued in a different direction.

The matter however, deserves some further attention. It appears to me that whatever the studies say, cameras have become a very popular weapon for social control – with all the connotations that carries. As a foreigner, it struck me that in London there is always a policeman getting footage of the participants in a demonstration. Police officers wander around pointing at the protesters with a lens as if they were pointing at the crowd with a gun. The scene is charged with aggression. There is a line which authority seems to be crossing disrespectfully. It is a brilliant example of how control tends to work at the level of the possible. Before the offence has taken place, there are already traces of the offender. Anyone is treated as guilty until evidence proves the contrary – and that can never be proved because there is always a possibility for a future crime.

Not long ago I came across an article in the Guardian about the use of cameras by the Essex police. The operation was called ‘Leopard’ and the idea was to film and photograph teenagers suspected of antisocial behaviour, and again the implication is that anyone is guilty in advance. An officer speaks to the Guardian while driving a patrol car:

There are some kids on the roof. We don’t know if they are causing damage or anything yet but we are going with other officers to try and surround it so they don’t get away.i

Kids have records before they are proven guilty, so by the time they are accused the records are already there to facilitate the process. This is a horrifying assault on youth and public space that once again is implemented in the name of public safety. In another interview sergeant Gavin Brooke says:

It’s a routine stop-check, as they would have got on any other day of the week, and we were just taking their photographs. And when they were in their groups walking around the estate we did have the video cameras on them, which had the desired effect because the kids didn’t like being filmed and they would generally either return home or leave the scene.ii

Image: Essex Police officer photographing teenager on a routine check

Cameras, then, have for the police the desirable effect of cleaning the streets of kids. The other key point that Goombridge introduced, as I said, was the artistic response to surveillance. Issues relating to CCTV systems provide an interesting field in which to explore the overlap between creativity and resistance. Given that there were three artists participating in the event – Alex Haw as a conductor and Manu Luksch and Mark Simpkins showing their work – one would have expected this overlap to have been an important focus of the event. In fact, except for the presentation by Manu, this theme was hardly discussed. Mark Simpkins couldn’t attend and Alex Haw remained modest, playing his role as a mere moderator.

Nik Goombridge brought up the topic almost unintentionally when he showed the barely controversial work of Anna Barriball. This piece consisted of a series of posters that were shown as part of the Art on the Underground programme. Most Londoners had the opportunity to see one that read: ‘I think I’m being watched’. Goombridge found it quite ironic to see one of these in Vauxhall Station, ‘exactly where the MI6 headquarters are located’. It is strange that for him the irony was in the fact that the poster was in Vauxhall Station when the London Underground is well known for its omnipresent cameras. And yet, even considering that the phrase refers to those cameras, it is hard to say whether it is ironic at all. If it is, it’s a very naïve type of irony; and yet it can’t be anything else but ironic given the context in which it’s exhibited. At first I thought it could be a typical example of the capacity of the system to include critical voices and still go unharmed. But what is critical in this piece? And what is the harm that it can produce? It could well be one more reminder to add to the continuous flow of announcements commuters are exposed to: ‘For your security 24h CCTV cameras are operating on the train and in the station.’ Therefore, ‘I think I’m being watched’.

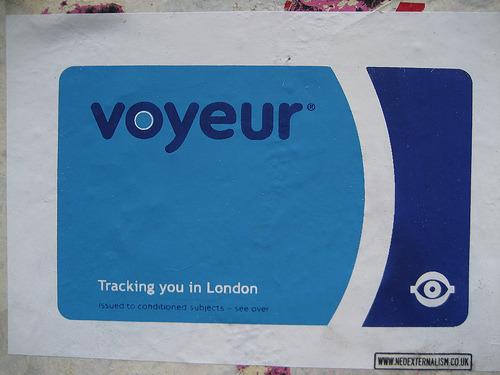

Other examples can be found that use irony in a more incisive way, as in the case of Oyster card stickers, in which the word ‘Oyster’ has been replaced by ‘Voyeur’ and ‘Transport for London’ by ‘Tracking you in London’. However, although it could be argued that these stickers induce discussion and provide a clever way of denouncement, if we wish to move beyond criticism we are better off looking for projects that actually manage to alter the dynamics of surveillance, diverting the flow of information and subverting the power structures underlying it. Within this strand we find projects like iSee by the Institute for Applied Autonomy, Video Sniffin’ by Mediashed, Signal Hijack by J. Wilbert or the ‘CCTV Filmmakers Manifesto’ by Manu Luksch, some of which were mentioned during the afternoon.

Image: Sticker by neoexternalism

Video Sniffin’, for instance, is a technique to pick up signals broadcast by wireless CCTV networks using a cheap video receiver. It can be used as a film-making device: while the actors perform in front of a wireless CCTV camera, the signal is being picked up by the video receiver. That way the hierarchical structures built by surveillance are shaken, and those under control are put actually in control of the process. Signal Hijack, on the other hand, builds on the same ideas but works inversely: instead of picking up signal, it broadcasts signal to a receiver. Using a powerful transmitter, it is possible to send a video signal to a wireless CCTV receiver, which means that one can broadcast all sorts of content to the monitors in the control room of that system.

While Video Sniffin’ and Signal Hijack work outside the law, Manu Luksch is interested in working precisely on the edges of it. The ‘CCTV Filmmakers Manifesto’ is based on the Data Protection Act 1998, the legal text that regulates the manipulation of information gathered by security systems. Manu Luksch’s Faceless is a film produced entirely under the guidelines of the Manifesto. In this case, the footage is not picked up by an alternative receiver, but is actually delivered to the artist by the very operators of the system. The Data Protection Act provides the ‘data subject’ with the right to request the footage in which he or she appears as long as the incidents that occur in the frame are ‘of biographical relevance’. Faceless is an experiment in which the artist adds a fictional layer on top of recovered CCTV footage, giving this information not only a completely different meaning but also a different way of being accessed since it’s taken out of its close circuit. However, such a bureaucratic nightmare carries with it an acceptance of law and struggles to find its mode of subversion within the strict compliance with the rules that it attempts to subvert.

Unfortunately, none of these questions received much discussion. How does surveillance actually operate? What are its effects on the movements of people, on their moods? What are the possibilities for resistance and deviation? And how can we move beyond mere criticism? Surprisingly enough it was Peter Fry, director of the CCTV User Group, and Paul Mackie, compliance director of CameraWatch, who led the discussion. Although these two speakers gave their presentations in apparent discomfort, I reckon the environment didn’t turn out to be as hostile as they expected. The critical voices remained shy and scarcely eloquent, turning the apologists for CCTV into the main protagonists of the event. Although seeing both sides in conversation was one of the appeals of the afternoon, the exchange wasn’t actually that satisfying.

Olga <olga AT ungravitational.net> works and lives in London. Her last media arts project is an attempt to establish conversation with control systems, www.ungravitational.net

Info

‘Surveing Surveillance’ was an event part of the TINAG festival 2008 and took place on the 26th of October. http://thisisnotagateway.squarespace.com/

iSee is one of the CCTV mapping projects. It is based in New York and it gives the user the less surveilled route to go from A to B. The project is available online. http://www.appliedautonomy.com/isee.html

Information about Video Sniffin': http://mediashed.org/videosniffin

Signal Hijack is available online with all the documentation necessary for it implementation: http://signalhijack.jhwilbert.com

Manu Luksch’s work is online at: http://www.ambienttv.net

Footnotes

i See http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/video/2008/may/30/operation.leopard ii See http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/video/2008/may/30/police.cameras

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com