History in the (Re)Making

In anticipation of the Jonestown massacre re-enactment, Eliot Albert explores the radical relationship between the repetition and production of historical events.

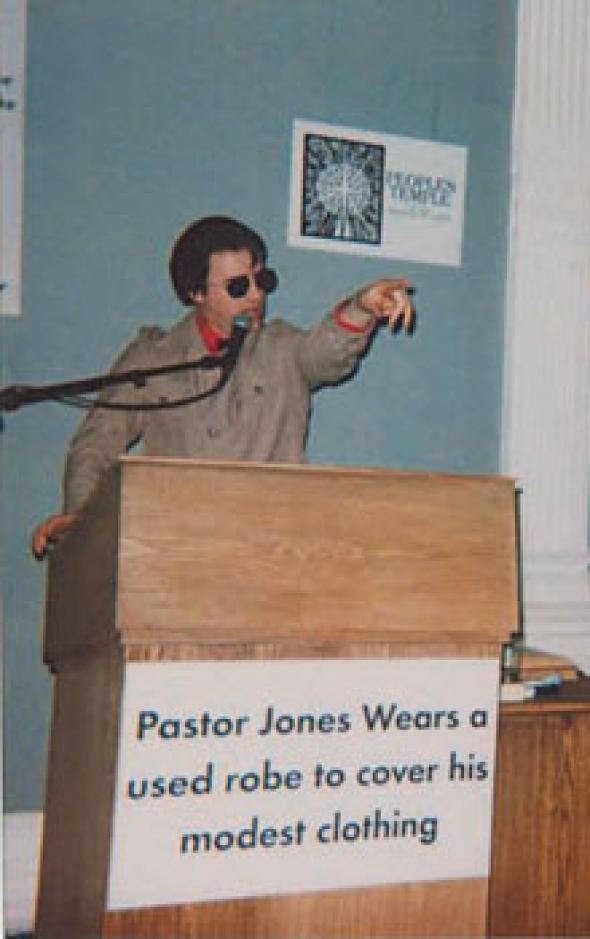

On May 26th 2000 the ICA hosted ‘The Promised Land’, a sermon and miracle healing by the Rev Jim Jones of the People’s Temple. The night was the inaugural event of Rod Dickinson’s current ongoing project: the Jonestown Re-enactment. This magnificently grandiose set of events will (funding and permission permitting) culminate in London with the public re-enactment of the mass suicide of ‘People’s Templars’ on November 18th 1978. The night on which Jones, together with the 914 men, women and children who lived in Jonestown – the beleaguered settlement constructed deep in the Guyanese jungle – took their own lives. Or, to quote Jones, it wasn’t suicide but “a revolutionary act”.

‘People’s Templars’, like the ‘subjects’ of Dickinson’s other work...no, not ‘subjects’…’objects’ maybe? Still no. How about ‘collaborators’? ‘Victims’? ‘Unwilling collaborators’? ‘Unknowing collaborators’? ‘Unwilling victims’? All of these things could be said of the various groups with which Dickinson works, but what is important here is not the character of those groups, but the nature of the contact, of the productive articulation formed between them and Dickinson. It is only by maintaining a precisely defined relationship with these groups that Dickinson is able to produce his work; indeed, the maintenance of this relationship is the work. For this relationship is one in which Dickinson quite literally joins his subjects; an act of becoming that is accomplished by producing the objects sacred to/studied by the given group, or by re-producing, re-enacting the actions or words of that group. The centrepiece of ‘The Promised Land’, the miracle healing or the production of a ‘cancer’ from a member of the congregation – was as much a theatrical sleight of hand at the ICA as it was when originally performed by Jones. Each instance of this performance was accompanied by an identical level of indeterminacy – blurring artifice and reality – between the description and the making of history. Each of Dickinson’s collaborations attempts, through the production of reality, to effect a change in that reality.

There is more, though, than this relationship, for like the other groups with whom Dickinson works (alien abduct-ees, crop circle enthusiasts and theorists – ’cerealogists’ – and new age tourists bran-dishing photos of Dickinson’s crop circles) Jones and the People’s Temple are all disparagingly dubbed, by those who make and claim the right to describe reality, ‘believers’. But what is made tran-sparently clear by Jones-Dickinson is that these people have all taken the political decision to refuse to believe. This perspective makes visible the overriding political import of Dickinson’s work, for these groups are united by their having taken the first step on the path to that revolution motivated by what Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt call ‘the will to be against’ (in Empire – for more click here). The great refusal to believe that the world – cosmic and lived human reality – is as the authorities such as church, state and official science say it is. This refusal, which is made manifest by Dickinson through Jones and his other erstwhile collaborators – genuine heretics all – can quickly become the demand for the world to be otherwise, and the first act in its remaking.

Eliot Albert <106106.2350 AT compuserve.com>

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com