Great Expectations: Governing Thames Gateway

The governance structure of the Thames Gateway is complex, fragmented and opaque. So how does this effect the governmental vision of participatory citizenship and sustainable communities? Penny Koutrolikou reports

The heart of the Government’s election manifesto earlier this year was a commitment to build a country ‘more equal in its opportunities, more secure in its communities, more confident in its future’. The Gateway provides both a symbol and a test case for that commitment.

– David Milliband, November 2005 (Minister of Communities and Local Governance 2005-06)

Despite repeated assertions of commitment to ‘good urban governance’ and ‘sustainable communities’ from those involved, the overall structure of the Thames Gateway project remains largely unclear. This raises serious questions about the rationale behind it and the way it will be implemented.[1] Like other regeneration projects, the very opacity of the process is, in practice, likely to render the rhetoric of local democracy hollow.

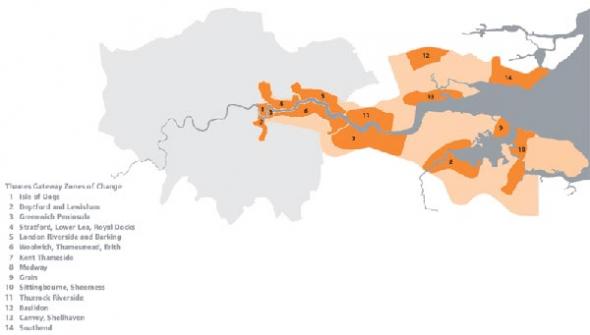

Thames Gateway is one of the largest – if not the largest – development projects in Europe. Apart from its size and development potential, its real importance lies in the great expectations attached to it – principally that it will resolve London’s ever-growing need for housing in a way that does not upset the already high property values of inner London. By displacing the problem to the poorer East via urban sprawl, strategists aim to develop new residential areas that could provide a large percentage of the ‘affordable’ housing currently lacking within the city. Additional arguments about economic development and maintaining competitiveness in the light of emerging global centres such as Shanghai are presented as further incentives to the city’s eastward growth.

The question that goes unasked in all the talk about sustainability is how the new ‘sustainable communities’ intended to take advantage of this housing can develop if the new city has no infrastructure and no local facilities to support it. What kind of residential areas will these be if, as seems likely, they are developed as atomised islands in the ‘uncharted waters’ of Thames Gateway?

Structural Adjustments

In such a large regeneration scheme, or more explicitly, in the construction and management of a city within a city, governance issues are indeed decisive. In the case of Thames Gateway there are several questions to be answered: first, how do the current governance structures communicate with the area’s residents and with other organisational structures; second, what are the governance structures that will oversee the delivery of the new projects; and third, how will these structures relate to the future communities of Thames Gateway?

Despite government commitments to ‘community involvement’, Thames Gateway is still primarily a central government led project. The strategic advisory group, Thames Gateway Strategic Board, consists of high-up government officials and ministers who put forward their different agendas and aims, negotiate about how they can be achieved, and provide the overall ‘strategic vision’ for the area. So far this approach has almost crippled the project since the private sector has failed to come up with the anticipated investments needed to push Thames Gateway forward. As a result, it seems plausible that future developers and investors will be offered further incentives – or even ‘carte blanche’ – in return for participating in the development of the region. The 2012 Olympics provide a further means by which to secure support for the development – both public and private. Indeed, geographically and economically, the Olympics represents the gateway to the Gateway.

If the governance structure for the ‘delivery’ of Thames Gateway is a defining factor for its future, the structures of this governance remain far from clear and so far there is limited public information on how it is supposed to operate. Similarly, the roles and responsibilities of the bodies involved are blurred in the overall complexity. Meaningful involvement in decision making and resource allocation on the part of the putative Thames Gateway community (new or old) will hardly be fostered by all this.

Trying to unravel the riddle that is governance, we encounter a broad range of partnership-based organisations reflecting the complexity and scale of the project. Besides the strategic group, the only body with an overall view is English Partnerships, but they mainly focus on development facilitation and land remediation. Other key players in the governance structure are the three Regional Development Agencies (London, East of England and South East). Then there are the ‘delivery organisations’ in the Thames Gateway charged with turning the ‘vision’ into reality: London Thames Gateway Development Corporation, Greenwich Partnership; Bexley Partnership; Thurrock Thames Gateway Development Corporation; Basildon Renaissance Partnership; Renaissance Southend; Kent Thameside Delivery Board; Medway Renaissance Partnership; and Swale Renaissance. These organisations represent both the delivery vehicles for development and, in some cases, local governance initiatives in the form of local partnerships. As a recent academic report puts it:Although Thames Gateway is promoted by central government as a coherent geographical entity united by a single strategic vision, in reality there are at least three distinct areas: London, Kent and Essex, each with its own management structure and set of public-private partnerships. As one member of the Thames Gateway board told us: ‘Basically what you have [in the Thames Gateway] are three separate areas, and things are different in all of them. In Kent you have the County Council and one developer for the whole area, but in Essex the County [Council] is working with three, four different [development] partners.’ [2]Additional organisations that have more of a lobbying and local governance remit include the Thames Gateway London Partnership, Kent Partnership and Essex Partnership whose boards are mainly made up of Local Authority officials and Councillors and other ‘important’ players such as major local developers.

Politicians and central government continue to reiterate that sustainable development and thriving communities depend on active community involvement. Yet the bottom-up ‘community participation’ component acting to influence and direct all these top-down structures seems to rely primarily on the London Thames Gateway Forum [http://www.ltgf.co.uk], the community and voluntary sector representatives that sit in the Local Authority Strategic Partnerships, and local campaigns. Already it seems that community involvement is going to be achieved primarily through community consultations over proposed developments and negotiations regarding the allocation of the relevant ‘planning gain’. In planning jargon this denotes the ‘community compensation’ that developers give in support of local facilities. Planning gain may include ‘affordable’ or special needs housing, provision of education facilities or open space, infrastructure for business, sustainable transport to meet the need created by the development, etc.

However, in these crucial negotiations over the location and extent of resources the developers and the Local Authority are the key players, with local groups primarily taking an advisory (or, at best, campaigning) role.

Gated or Ghetto Gateway?

Adrift in this sea of organisations and partnerships one starts to wonder about their actual functions, responsibilities and powers, their potential overlap and duplication, lack of transparency and, therefore, of accountability. This ‘problem’ has of course been acknowledged by politicians and academics alike, but in the end the fundamentals of governance mitigate against ‘solving’ it. As the paper quoted above describes, the coordination of the various organisations remains in the hands of the state:Although a limited degree of co-ordination for the whole of the Thames Gateway area has been provided by a joint operating committee including the chairmen and chief executives of the three RDAs (Regional Development Agencies) involved (…) and representatives from the three area management boards, real strategic oversight is provided directly from central government.[3]If the key structures providing oversight for the development are dominated by government officials and interest-led members (such as representatives of property consortiums like Land Securities), to what extent are issues of sustainability, build quality and local provision up for discussion? Private support is too essential to jeopardise.

Given the housing targets set for Thames Gateway, the project will most likely be delivered through the development of large plots of land by consortiums of developers. This is likely to result in self-contained residential developments. In negotiations over planning gain Local Authorities tend to recognise the need to balance developers’ profits against the need for local infrastructure and service delivery. However, since this process of ‘balancing’ takes place behind closed doors and under pressure from central government to push these developments forward, it is likely to be seriously biased in the developers’ favour.

Rather than checking their excesses, the ‘distributed’ power structure of the Thames Gateway development seems likely to assist developers in the continuation of the ‘state of emergency’ announced by the 2012 Olympics. In line with central Government policy, power is displaced from the planning departments of the Local Authorities to the Urban Development Corporations (such as the Thames Gateway UDC) in order to deal with the ‘emergency’ of achieving development results. All this favours the scenario of a Thames Gateway of fragmented, car dependent enclaves that turn their their backs on existing (and less affluent) local centres and communities while consuming their facilities. If the Institute of Public Policy Research’s recent report ‘Gateway People’ (2006) can be relied on, the middle class are not going to be early adopters of the Thames Gateway brand - Essex just isn’t sexy enough in ‘culture and heritage’ terms. Instead, the new developments could end up predominantly a dumping ground for those forced out of London. But the middle class residents who do come will likely concentrate in a series of insular enclaves, producing a fragmented urban collage reminiscent of the complex, opaque and fragmented structure of the Thames Gateway’s governance. Not sustainable ‘urban villages’ but gated Gateway communities amid Gateway ghettoes.

Any prospect (or threat) of the democratic and community led ‘civic Gateway’ hailed by New Labour- replete with participatory design, participatory budgets, citizens’ juries, neighbourhood charters and possibly community managed assets - is effectively buried under the dense meshwork of developer-dominated governance.

[1] For example, the EU Ministerial Informal on Sustainable Communities in Europe (Bristol Accord, 2005) and John Prescott’s ‘sustainable communities’ agenda for the UK.

[2] ‘The South East Region’, by P. John, A. Tickell and S. Musson, in England The State of the Regions, J. Tomany and J. Mawson (eds.), Bristol: The Policy Press, 2002.

[3] Ibid.

Penny Koutrolikou <p.koutrolikou AT bbk.ac.uk> is a lecturer in regeneration and community development at Birkbeck College, and she is currently working on the effects of local development and governance on inter-group relations

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com