Goatherds in Pinstripes

Free marketeers who argue against private property rights on the internet, intellectual property lawyers trying to emulate the environmental movement – what could possibly account for such peculiar behaviour? Gregor Claude digs up the digital commons

Digitopia seems to have died. A couple of years ago received wisdom had it that the internet was a new realm of freedom, unbound by the regulations and restrictions that controlled life offline. The internet seemed to exist in the absence of law, outside of any particular state’s jurisdiction. It was as if law had been transcended through information technology. But more recently we have seen a string of copyright-related lawsuits, legal intimidation and legislation. Napster was shut down by a judge and then bought by one of the plaintiffs; Princeton computer science academic Edward Felten was threatened with legal action by the Recording Industry Association of America if he published his research into encryption; Russian programmer Dmitri Sklyarov was arrested under the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act because he wrote software allowing people to read Adobe Software’s encrypted version of Alice in Wonderland, a text already in the public domain and legally available for free. These events have made it abundantly clear that the law had been there all along.

The latest project to come out of Washington, that legislative workshop of the world, is the Security Systems Standards and Certification Act (SSSCA), a proposed bill that would mandate built-in hardware copy-control protection in all new PCs and consumer digital media devices, from your walkman to your computer. According to Wired, who have obtained a draft of the SSSCA, the law would create new federal felonies, punishable by five years in prison and fines of up to $500,000, for ‘anyone who distributes copyrighted material with “security measures” disabled or has a network-attached server configured to disable copy protection.’ It would be illegal to create, sell or distribute any device capable of ‘storing, retrieving, processing, performing, transmitting, receiving or copying information in digital form’ unless they contained certified copy protection technology. Hang on to your old computer because it just might be more functional than next year’s model.

The law was drafted in close consultation with none other than global culture industry giant, the Walt Disney Corporation. Disney’s executive vice president Preston Padden claimed the law was an ‘exceedingly moderate and reasonable approach.’ Padden’s idea of reasonable and moderate is chilling; at an event in December 2001 he dismissed criticism of the SSSCA, saying ‘There is no right to fair use. Fair use is a defence against infringement.’ In copyright law, fair use means the right to use copyright material, regardless of the wishes or intentions of the copyright owner. This means that when you buy a book, you can quote it elsewhere, criticise it or cut it into bits and make a work of art if you are that way inclined. For Disney’s Padden, the fair use provisions of copyright law amount to an unfair tax on the copyright holder, as if public access to copyrighted knowledge or culture is some kind of pinko perversion. It’s as if montage was a criminal act. Next time you feel that cut and paste urge coming on, make sure you look over your shoulder and check if Big Mickey is watching you.

When this is what passes for reasonable in Washington and beyond, it comes as no surprise that the nucleus of an attempt to counter this copy protectionism is emerging. Increasingly, arguments against stronger intellectual property rights deploy the concept of the ‘digital commons’ (see Mute 20). November 2001 saw two key moments in this emergence. The first was the release of Lawrence Lessig’s The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World. Following on from his 1999 book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, Lessig’s new book reads like a manifesto. It doesn’t pretend to hide its goal of doing for the digital commons what Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring did for the natural environment in the 1960s. The second key moment, the Conference on the Public Domain held at Duke University, was co-organised by the Center for the Public Domain and Duke’s James Boyle. The conference brought together the leading figures of the digital commons debate, focussing on Boyle’s keynote paper, ‘The Second Enclosure Movement and the Construction of the Public Domain.’

These two events bring into sharp focus the critique of intellectual property and defence of the public domain or commons, and could come to be seen as the founding moment of an important new campaign. Whatever their future, they have set the tone, established the language and introduced the concepts of a challenge to the privatisation of culture online. Yet both Lessig’s and Boyle’s approaches have significant weaknesses. But before discussing where they’re coming from… what are they talking about?

THE COMMONS: FROM GOATHERDS TO SERVER FARMSSo what is the digital commons? First, an important clarification: we are not talking about commons as in the Parliamentary House of Commons, but commons as in the village commons, a resource held in common. Even without peculiarly British confusions, Boyle acknowledges that the commons can be a ‘distressingly messy’ concept, subject to many different interpretations. Here is Lessig’s description:

It is commonplace to think about the Internet as a kind of commons. It is less commonplace to actually have an idea what a commons is. By a commons I mean a resource that is free. Not necessarily zero cost, but if there is a cost, it is a neutrally imposed, or equally imposed cost… No permission is necessary; no authorisation may be required. These are commons because they are within the reach of members of the relevant community without the permission of anyone else… The point is not that no control is present; but rather that the kind of control is different from the control we grant to property.Lessig goes on to give examples of commons: Central Park, public streets, Fermat’s last theorem, Linux source code. These resources exist outside the normal rules of property. It’s not that commons are the opposite of property, but they lack property’s key feature: the exclusive right to use or access the object owned.

In a world based on the production, circulation and exchange of privately owned commodities, the commons have always proven a bit of a headache for mainstream economists. Today’s discussion of the commons is informed by an influential paper published in Science in 1968 by Garrett Hardin, called ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’. In it, Hardin argues that resources held in common are doomed to inefficient misuse. ‘Picture a pasture open to all,’ begins Hardin. As the story goes, each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. Adding one more animal to his herd imposes a shared cost (goats gotta eat) on all the herdsmen, but the gain of the one extra animal belongs exclusively to its owner. Alas, all the herdsmen come to the same conclusion. As Hardin continues with the literary flair of a modern Ezekiel, ‘Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit – in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.’

Now you might think this is a misanthropic and ahistorical Malthusian argument for restraint whose assumption that ancient goatherds can stand in for the modern, rational individual acting as a self-maximising subject could be dispelled by a look at some elementary anthropology, but never mind that now because the essay has been hugely influential in both the environmental movement and in economics. It is important here because it sheds light on why the digital commons is different.

Lessig spends the first hundred pages of his book detailing the ‘building blocks’ of the digital commons – he is providing an exhaustive account of why and how the internet functions as a commons. If you don’t know how the internet works and want to find out, start here. This is a fascinating tour of what makes the net a unique medium that will in places leave you awestruck at the untapped potential of this technology, and even more awestruck at the genius of the scientists and engineers who put it together. If you know this already, prepare to skim read. But for Lessig, the main point of going through this technological detail is to demonstrate how the physical network of the internet, as well as the open source software it runs on, is a common resource that all can access without discrimination.

This is not to say that everything on the net is free and uncontrolled. Servers and cables and so on are always owned by some entity; access to many files is restricted. Of course there are private roads, Lessig would argue, but the road network is still a common resource. Or take another example: the routers that send data packets across the internet don’t discriminate based on the content of the data packet, they treat all packets equally. This is a ‘dumb’ or ‘end to end’ network: all data processing takes place at the network nodes rather than in the network. It would be conceivable to run a more centralised network, where for example different data types would be routed according to different priorities. But with the internet today, all the network does is transmit data: it is a neutral network. So while the routers are not your property, you use them as a common resource when you connect to the network.

So the internet is a commons, but how can it escape the fate of Hardin’s greedy goatherds? The internet is what economists call a ‘nonrivalrous resource’. You can have your cake, eat it, and distribute a round for all your friends at the same time; a nonrivalrous resource is undepletable. Digital media on the internet is in a permanent glut; this is an economy not of scarcity but superfluity. Bottlenecks might occur in bandwidth or storage space, but not in content.

There is one final aspect to the digital commons, and one that provides the strongest argument in favour of maintaining the internet as a commons. As Lessig puts it, ‘all the stuff protected by copyright law… depends fundamentally upon a rich and diverse public domain. Free content, in other words, is crucial to building and supporting new content.’ The case can be made even more strongly: the raw material of culture is culture. Creativity always appropriates the results of past creativity. New culture continually re-purposes already existing culture, making it into something new. Digital media, in addition to allowing more perfect control, also allows more perfect appropriation.

This capacity for appropriation opens up new possibilities for culture. It also points to the internet as more than just a nonrivalrous common resource, but as a resource that actually increases in both quality and quantity the more it is used. The ability to exploit, repurpose, consume and appropriate digital content as a commons creates a virtuous cycle, acting as a cultural accelerator.

THE CHICAGO SCHOOL AND THE CASE FORMAXIMUM IP CONTROLDisney’s Padden and the SSSCA also use the language of innovation. But instead of seeing the locus of innovation at the level of a dispersed network, drawing on and contributing to a common digital resource, they see large culture corporations as the incubators of creativity. For them, tight copy protection is necessary to allow these creative corporations to flourish.

This view is informed by ‘Chicago School’ economics, the tradition of free market economics associated with Milton Friedman and others that emerged in the 1960s, shaped the Reagan-Thatcher years, and is still influential today. For the Chicago School, resources are always more efficiently used when distributed by the market. The legal wing of the Chicago School, initiated by judge and scholar Richard Posner, is known as the ‘law and economics’ approach and is today the most widely accepted doctrine among the US Judiciary. For law and economics, law is not seen as an instrument of justice or of social order, but above all as a tool to help markets run smoothly and to promote social wealth. Accordingly, all social phenomena could be understood as the result of rational choices based on costs and benefits, and law was no different. Ascendant in the 1970s and effectively institutionalised under Reagan in the 1980s, law and economics transformed the application of anti-trust law. What was once a populist measure to check the power of big business became a means of smoothing the path for US corporations.

Preston Padden really does think that his approach and that of the SSSCA is ‘exceedingly moderate and reasonable.’ From their point of view, the internet is an enormous risk. For ‘content companies’ like Disney, it is imperative to maintain exclusive control over their copyright material. They look at the internet and see an unstable and uncertain market they cannot trust. They cannot guarantee the integrity of their goods. The cost of this uncertainty, and of any potential losses, must be taken into account, and the consequence (threatens Disney) is that they will not be able to support the same levels of investment in developing new content.

From this perspective, the internet has created an imbalance in the market, and legislation is needed to restore market equilibrium. If the cost of copying has plummeted, then the strength of copy control should be increased in equal and opposite measure. The justification for this control is the free market assumptions of law and economics (though Judge Posner, infamous as a contrarian, has argued against such a conclusion). The logic of control today is not alien to the market, but rather emerges from it.

LESSING, THE FREE MARKET, AND THE INTERNET ANOMALYIt seems peculiar at first that there are so many similarities between this argument and Lessig’s. Indeed, as it turns out, he is something of a Chicago School prodigal son: Lessig was Posner’s clerk from 1989 to 1990. Though they evidently have plenty of disagreements, Lessig has conceded Posner’s influence: ‘We are all law-and-economists now.’

Lessig’s free market proclivities periodically pop up through his book like awkward spotty teenagers. ‘Though most distinguish innovation from creativity,’ he writes, ‘or creativity from commerce, I do not’. And there I was thinking that always casting culture and experimentation in terms of commerce was part of the problem. In a later example of failing to distinguish markets and innovation, he writes, ‘coders learn what free markets have taught since Smith called them free: that innovation is best when ideas flow freely’.

So how does Lessig square his passion for the market with the digital commons? In one of his important differences with the traditional Chicago School, he is strongly anti-monopoly. Lessig echoes the concerns articulated by free market theory of the late 1980s and early ‘90s. At that time, fashionable economic theory sought to re-emphasise the role of the entrepreneur in contrast to the situation J K Galbraith had described in the ‘The New Industrial State’. Galbraith’s analysis of the post-war ‘industrial system’ sketched a bureaucratic system in which businesses, governments and unions had all ceded control to a quasi-autonomous technostructure resistant to nearly all attempts to alter it. After the first wave of the Chicago School sought to deregulate corporations and cut them loose from this technostructure, later Chicagoans became frustrated with the notion that businessmen were paralysed by structure, and fell on the idea of celebrating the innovation of the entrepreneur. Lessig echoes this repeatedly in discussions of the role of the digital commons in ‘lowering the barriers to entry’ into a market. It is as if he aspires to an internet agora where intellectual and cultural producers are not held down at the neck by giant copyright corporations, but are rather cultural entrepreneurs or knowledge entrepreneurs who enter the marketplace of ideas or the marketplace of culture, whose barriers to entry are minimised by state regulation.

But most importantly for Lessig, the internet is the great exception to the market rule. He writes, ‘to the extent a resource is physical – to the extent it is rivalrous – then organising that resource within a system of control makes good sense. This is the nature of real-space economics; it explains our deep intuition that shifting more to the market always makes sense. And following this practice for real-space resources has produced the extraordinary progress that modern economic society has realised... But perfect control is not necessary in the world of ideas. Nor is it wise.’ He continues, ‘The digital world is closer to the world of ideas than to the world of things.’ In the end, then, the digital commons is a technical issue: it is only because digital media frees information from the ‘real-world’ printed page that it becomes inefficient to organise ideas as tightly controlled property like books.

Of course, it’s not that this diminishes Lessig’s campaign particularly, but it certainly gives us a better idea of what it is about. It is striking that underneath it all, Lessig’s digital commons is nothing more than a well functioning market. If the right laws are passed and the right code implemented, a harmonious free market will deliver innovation. At a time of severe ‘market creep’, when market relations persistently encroach on life, the case for campaigning for its extension through cyberspace is less than convincing.

BOYLE'S RHETHORICAL LOBBYJames Boyle is less hung up on the market; he is more likely to talk about market failure than about market efficiency. He comes from the ‘critical legal theory’ tradition, drawing on postmodernists like Michel Foucault and Stanley Fish to understand law as a ‘discourse of power’. But for all Boyle’s postmodernist references, his approach is much more like the traditional single-issue lobby that Washington knows how to work with.

His reference point and role model is the environmental movement. As he describes it, it is a loose coalition of groups and interests. Their aims, strategies and tactics diverge, but they share a unifying concept of ‘the environment’. It is a concept that is in many ways a fiction, notes Boyle, but it is a rhetorical strategy that alone can bring a large group of varied interests under one umbrella. Accordingly, the campaign for the digital commons for Boyle begins with its rhetorical invention: ‘the language of the public domain will be used to counter the language of sacred property’.

But the problem with the linguistic approach of the postmodernists that Boyle adopts is particularly stark when applied to the idea of a public domain. Can a public domain or common resource really be built on nothing more than a structure of belief and a rhetorical strategy? Conspicuously absent in this proposal is… the public. Public spaces, whether real or digital, are so easily enclosed or privatised because the public claim to them is so weak. The privatisation of public life began as a political process long before the internet hit the shelves, and it is no surprise this privatisation is reflected online. A linguistic postmodernism that reads all the world as text enables a rewriting around the problem of a diminished public and political sphere rather than addressing the problem and attempting to resolve it. For Lessig, the digital commons can exist because it is a technological anomaly not subject to market organisation. This allows him to ignore the thorny issue of the public. The danger is that Boyle’s linguistic first step may in the end be just as empty as Lessig’s technological one.

The environmental impulse could too easily echo the problem by creating a coalition to provide an interface between government and a minority lobby, perhaps with a broad base of passive public moral and financial support. The politics of the environment is too often that of self-appointed guardians of a resource that the general public and big business combine in ignorance and avarice to despoil and pollute. Again, this is a model dangerously conducive to building on public passivity rather than challenging it.

Boyle’s use of environmentalism reflects the limits of political possibility that exist today. Recognising the need for an information politics, he takes a prefabricated contemporary political form and wants to pour information politics into it. But to have real substance, the public domain can’t do without the public.

INFORMATION POLITICS - INFORMATION FOR WHAT?The digital commons debate opens up a field of possibilities, my criticism notwithstanding. Boyle and Lessig are two of the great pioneers of that opening. Many others have now begun to think about how these issues can be used politically. Most ambitiously perhaps, Michael Hardt of Empire notoriety has recently been working on intellectual property and other forms of what he calls ‘immaterial property’, arguing that they present the opportunity for making a new communist case against private property as a whole.

Whether or not any of this work leads anywhere, there is still an important unanswered question that the issue of information control runs up against: information for what? Why should anyone care who controls knowledge if there is no perception of a particular need for it? Programmers need the software source codes that the free software movement is fighting to make freely available because they are the tools of their trade. People get upset about the file-sharing issue, exemplified by the Naptser case, because the lawsuits and legislation pushed by industry lobbies are a barrier to the steady, cheap flow of their cultural consumption. The concern for control over biotech patents is rooted in either a precautionary fear of the possibilities of science, or from a different angle, a concern with the supply of medicine to, and the exploitation of, ‘underdeveloped’ countries. These are issues of concern, but nevertheless are a narrow focus. The missing question is, ‘knowledge for what?’

Gregor Claude <gregor AT zoom.co.uk> is at the Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths and is writing a PhD on digital media, copyright and the culture industries

Conference papers from the Conference for the Public Domain [http://www.law.duke.edu/boylesite//papers.pdf]

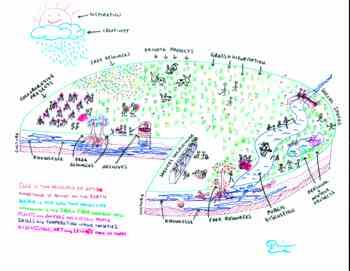

Drawing made in Mexico by Quim Gil, inspired in the rural life of states like Chiapas, in which traditional common resources and common activities are being pushed away agressively by the corporations' tentacles and the ‘public’ institutions (ignoring the public interests). He is travelling through Latin America in the context of an online journalism project: From América, With Love (thespiralweb.org/desdeamericaconamor). He is also participating in the design and development of collaborative projects compatible with the concept of 'digital commons' such as metamute.com and thespiralweb.org (an open-sourced political party).

Follow-up on metamute.com

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com