Getting Closer to Bigger Screens

The BBC's Live Sites 2012 program is set to roll out 60 big screens in urban centres around the UK by 2012. Considering the vague agenda currently guiding their use, Richard Wright asks whether these big screens will ever open themselves to creative use or simply remain giant TVs controlled by giants

From early film theorists like Siegfried Kracauer to present-day sociologists like Richard Sennett, an ongoing concern has been expressed with the way late modernity has refashioned our cities into a series of what Marc Augé calls ‘non-places’. The uniform design, contemporaneity and functionality of these new spaces has been perceived as obstructing the narrative history and symbolic interpretations that had been the basis of their prior identity. First observed in expansive shopping plazas and sprawling airports, the apologists for these spaces waited in vain for ‘form follows function’ to give rise to ‘place follows space’. More recently this ‘placelessness’ has assumed a temporal dimension as well, as urban centres are increasingly able to change their facades, fittings and functions – transforming from retail outlets to exhibition halls to music venues with as little friction as changing a film set. The elusive ‘sense of place’ must now be defined, if at all, through a programme of events or as a site of performances rather than static architectural features. Either way, what technology can accommodate the demand for a dynamic environment more efficiently than a medium that supports the daily scheduling of video displays, animated info kiosks and Bluetooth alerts? The study of this interchange of media traffic and public traffic has started to be identified under the umbrella term of ‘Urban Media’ and it was this term that was used to describe the second Urban Screens conference in Manchester, hosted at Cornerhouse. Although cities like London and New York are full to bursting with commercial video displays showing 24 hour adverts, the genre of the ‘urban screen’ has come to refer to those intended for ‘cultural content’. This generally means screens for non-commercial use but also, increasingly, as a means for governing bodies to actively shape the cultural functions of public space, to advance current public policies such as ‘community building’ and urban regeneration. The conference proceedings described the host city of Manchester as ‘the first city of the industrial age’ and therefore a fitting recipient for the latest experiments in town planning. Yet a quick walk down the road into Manchester’s town centre revealed that there is very little left of this ‘first city’ since its heartlands were almost completely reconstructed after the IRA bombing of 1996. The homogenisation caused by its endless window fronted retail thoroughfares implies that Manchester will also be the first city without any recognisable form, indistinguishable from most other town centres in the UK. This missing ‘sense of place’ now causes concern for the same town planners that so effectively effaced it. One response is to use screens that can renew and restage the exterior façades of the city through their changing programme of video content.

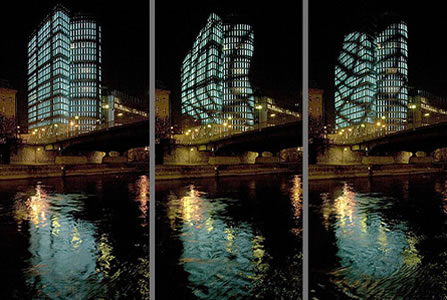

Image: Alexander Stublic, Twist and Turns Urban Screens was curated by Dr Susanne Jaschko and included a range of institutional supporters such as Arts Council England, various local authorities and agencies from the City of Manchester itself. One of the strongest driving forces behind the programme itself seemed to be the BBC. It was their ongoing Big Screens project that originally blessed Manchester’s Exchange Square with the UK’s first permanent public screen back in 2003. It was this influence and location that seemed to give the conference as a whole an emphasis on the role of large city centre screens. There were many critical cultural commentators and practitioners in evidence at this conference, from media archaeologists such as Erkki Huhtamo to curators like Beryl Graham and Mike Stubbs, Director of FACT in nearby Liverpool. Many of the presentations were case studies and interventions from visual artists, architectural groups and new media designers. Yet somehow the plenary discussions always seemed to return to orbit around the figure of monumental video displays, in a way eerily reminiscent of an earlier generation of video artists who had been drawn to the bosom of the major television broadcasters. The conference felt much like a platform for the public policy makers in this country, with the agenda focused on how to integrate new screen technologies permanently into public space in a planned way. The UK’s urban screens strategy has been dominated by the BBC’s ‘Big Screen Network’. This undertaking is driven by the BBC’s updated remit of ‘public space broadcasting’ and since 2003 has resulted in the installation of eight ‘Big Screens’, 25 meters square, in major cities such as Manchester, Leeds, Hull and Bradford. By the time of the Olympics, a much larger network called ‘Live Sites 2012’ is planned that will increase their number to 60 screens, all equipped with live camera feeds, Bluetooth uploading and networked streaming capabilities. For the BBC it is about providing a local site for national occasions such as Wimbledon, Eurovision or the Proms, similar to combining a public television service with the events management of a tourist board. Their technology partners are Philips who manufacture the biggest Vidiwall screens, mainly used in sports stadiums but which are now finding an expanding market through public screens. The conference and artists' commissions were funded by Arts Council England, for whom we might imagine this represents an attractive platform for ‘participatory arts’ and reaching ‘new audiences’ now that prior opportunities for involvement in mass media such as television broadcasting have moved beyond their reach. The purchase of the screens is borne by City Councils for whom the screens offer an opportunity to ‘re-animate city centres’. In practice this could mean drawing in lively crowds to their nondescript precincts through what is termed by some urban theorists ‘the production of place’, but particularly the kinds of places where that liveliness can be administered, programmed and evaluated. This is in turn is allied to the wishes of the property developers who would like to orientate those bored and undirected crowds away from casual vandalism and to stimulate local business (often deterred by developer's concentration on higher rent residential properties). So, the level of expectation from big Urban Screens is high as are the hopes to align the thinking of these big players. Yet the diversity of interests and remoteness of the agencies involved sometimes made it difficult to extract even the most basic information. What has actually been achieved with these big screens? Are expensive big screens even sustainable? A huge programme of hundreds of videos and interactive pieces attempted to answer the first question and suggest possibilities for the second. During the first day of the conference we were taken down to a specially erected screen in All Saints Gardens for the launch of the BBC’s flagship ‘Bigger Picture’ Arts Council funded commissions, for which four artists had been selected from 300 entries. The works included participatory film-making projects such as New York based Perry Bard’s 2008: Man with a Movie Camera – a new version of Vertov’s urbane avant-garde classic which was compiled out of footage submitted through the projects web site. Juneau Project’s Honourable Ordinaires was another participatory film animated from Sheffield school kids' designs for contemporary heraldic motifs and coats of arms. Susan Pui San Lok’s DIY Ballroom/Live used the opposite and more difficult approach by screening sequences of amateur ballroom dancers in order to prompt the audience into joining in a spontaneous take-your-partners twirl across the pavement. Esther Johnson’s Celestial was a lyrical short documentary about the sky – its shots of cloud and weather patterns frequently appearing to stand in for views of the horizon that the swollen screens now obscured.

Image: Alexander Stublic, Twist and Turns Urban Screens was curated by Dr Susanne Jaschko and included a range of institutional supporters such as Arts Council England, various local authorities and agencies from the City of Manchester itself. One of the strongest driving forces behind the programme itself seemed to be the BBC. It was their ongoing Big Screens project that originally blessed Manchester’s Exchange Square with the UK’s first permanent public screen back in 2003. It was this influence and location that seemed to give the conference as a whole an emphasis on the role of large city centre screens. There were many critical cultural commentators and practitioners in evidence at this conference, from media archaeologists such as Erkki Huhtamo to curators like Beryl Graham and Mike Stubbs, Director of FACT in nearby Liverpool. Many of the presentations were case studies and interventions from visual artists, architectural groups and new media designers. Yet somehow the plenary discussions always seemed to return to orbit around the figure of monumental video displays, in a way eerily reminiscent of an earlier generation of video artists who had been drawn to the bosom of the major television broadcasters. The conference felt much like a platform for the public policy makers in this country, with the agenda focused on how to integrate new screen technologies permanently into public space in a planned way. The UK’s urban screens strategy has been dominated by the BBC’s ‘Big Screen Network’. This undertaking is driven by the BBC’s updated remit of ‘public space broadcasting’ and since 2003 has resulted in the installation of eight ‘Big Screens’, 25 meters square, in major cities such as Manchester, Leeds, Hull and Bradford. By the time of the Olympics, a much larger network called ‘Live Sites 2012’ is planned that will increase their number to 60 screens, all equipped with live camera feeds, Bluetooth uploading and networked streaming capabilities. For the BBC it is about providing a local site for national occasions such as Wimbledon, Eurovision or the Proms, similar to combining a public television service with the events management of a tourist board. Their technology partners are Philips who manufacture the biggest Vidiwall screens, mainly used in sports stadiums but which are now finding an expanding market through public screens. The conference and artists' commissions were funded by Arts Council England, for whom we might imagine this represents an attractive platform for ‘participatory arts’ and reaching ‘new audiences’ now that prior opportunities for involvement in mass media such as television broadcasting have moved beyond their reach. The purchase of the screens is borne by City Councils for whom the screens offer an opportunity to ‘re-animate city centres’. In practice this could mean drawing in lively crowds to their nondescript precincts through what is termed by some urban theorists ‘the production of place’, but particularly the kinds of places where that liveliness can be administered, programmed and evaluated. This is in turn is allied to the wishes of the property developers who would like to orientate those bored and undirected crowds away from casual vandalism and to stimulate local business (often deterred by developer's concentration on higher rent residential properties). So, the level of expectation from big Urban Screens is high as are the hopes to align the thinking of these big players. Yet the diversity of interests and remoteness of the agencies involved sometimes made it difficult to extract even the most basic information. What has actually been achieved with these big screens? Are expensive big screens even sustainable? A huge programme of hundreds of videos and interactive pieces attempted to answer the first question and suggest possibilities for the second. During the first day of the conference we were taken down to a specially erected screen in All Saints Gardens for the launch of the BBC’s flagship ‘Bigger Picture’ Arts Council funded commissions, for which four artists had been selected from 300 entries. The works included participatory film-making projects such as New York based Perry Bard’s 2008: Man with a Movie Camera – a new version of Vertov’s urbane avant-garde classic which was compiled out of footage submitted through the projects web site. Juneau Project’s Honourable Ordinaires was another participatory film animated from Sheffield school kids' designs for contemporary heraldic motifs and coats of arms. Susan Pui San Lok’s DIY Ballroom/Live used the opposite and more difficult approach by screening sequences of amateur ballroom dancers in order to prompt the audience into joining in a spontaneous take-your-partners twirl across the pavement. Esther Johnson’s Celestial was a lyrical short documentary about the sky – its shots of cloud and weather patterns frequently appearing to stand in for views of the horizon that the swollen screens now obscured.

Image: Susan Pui San Lok, DIY Ballroom/Live These pieces seemed intended to demonstrate the BBC’s commitment to pursuing some form of ‘participatory culture’ in its future plans. During the final session of the first day – ‘Towards a New Economy of Urban Screens’ – Mike Gibbons, head of the ‘Big Screens Network’ and now head of ‘Live Sites 2012’, presented their current strategy. The introduction of urban screens to the ‘community building’ agenda centred around ideas of ‘communal experience’ rather than opening up the floodgates of anything approaching ‘user generated content’. Some reasons were not hard to find considering that the rules of UK broadcast regulations make it officially impossible for them to accommodate any live, unmoderated material (pushing ‘participation’ further towards gaming). Elsewhere the Big Screen Network is still tied into the thinking behind its origins in the temporary screens erected for the Queens Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2002. Outside such state events, Big Screen content is currently dominated by BBC news and sports with the four artists commissioned for the ‘Bigger Picture’ presumably constituting a foray into more interactive, open ended programming. At times it sounded like they had not gone beyond a scaled up version of the traditional television set combined with a scaled down form of tourist attraction. As Gibbons went on to explain, in order for a city council to join the Big Screen Network it is required of them to offer a site that guarantees a high footfall, facilities such as cafés and an events programme (so that people know when to watch it, just like the Radio Times). Perhaps the Beeb could find further inspiration from its golden age of public service broadcasting by recreating the period when those that were too poor to afford a television set would go out into the streets and stand together watching through the Rediffusion shop windows. There were other speakers who presented very different models from the BBC’s Reithian traditions yet somehow still retained its desire for imposing grandeur. Kirsten Gray represented an organisation called Victory Media Network which runs the Victory Square complex in Dallas, Texas. This ‘Outdoor Digital Art Gallery’ shows mainly short films and ‘video art’ and is primarily sponsored by Target – the US retail clothing chain. Mark Bennett of Target described his company’s interest in building its image by aligning itself with ‘art’. Victory Square is an incredibly technically ambitious arrangement of eight screens mounted on two opposing walls of a retail centre, each wall supporting four 20 metre by 30 metre screens, each of which can be independently manoeuvred on sets of rails into a variety of configurations. However, although it is hard to imagine moving image work which lends itself to such manoeuvres without having been produced specifically for it, Victory Media only buys in work and does not actually commission artists. In fact the only art actually commissioned for this multiple screen site seems to be produced for Target itself – a series of 3D animations of marbles and butterflies designed to slip across the precisely choreographed screens, branded in the company’s red and white livery and given such titles as ‘Art Evokes’ and ‘Art Connects’ (see http://www.mefeedia.com/entry/target-art-evokes/3850160/).

Image: Susan Pui San Lok, DIY Ballroom/Live These pieces seemed intended to demonstrate the BBC’s commitment to pursuing some form of ‘participatory culture’ in its future plans. During the final session of the first day – ‘Towards a New Economy of Urban Screens’ – Mike Gibbons, head of the ‘Big Screens Network’ and now head of ‘Live Sites 2012’, presented their current strategy. The introduction of urban screens to the ‘community building’ agenda centred around ideas of ‘communal experience’ rather than opening up the floodgates of anything approaching ‘user generated content’. Some reasons were not hard to find considering that the rules of UK broadcast regulations make it officially impossible for them to accommodate any live, unmoderated material (pushing ‘participation’ further towards gaming). Elsewhere the Big Screen Network is still tied into the thinking behind its origins in the temporary screens erected for the Queens Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2002. Outside such state events, Big Screen content is currently dominated by BBC news and sports with the four artists commissioned for the ‘Bigger Picture’ presumably constituting a foray into more interactive, open ended programming. At times it sounded like they had not gone beyond a scaled up version of the traditional television set combined with a scaled down form of tourist attraction. As Gibbons went on to explain, in order for a city council to join the Big Screen Network it is required of them to offer a site that guarantees a high footfall, facilities such as cafés and an events programme (so that people know when to watch it, just like the Radio Times). Perhaps the Beeb could find further inspiration from its golden age of public service broadcasting by recreating the period when those that were too poor to afford a television set would go out into the streets and stand together watching through the Rediffusion shop windows. There were other speakers who presented very different models from the BBC’s Reithian traditions yet somehow still retained its desire for imposing grandeur. Kirsten Gray represented an organisation called Victory Media Network which runs the Victory Square complex in Dallas, Texas. This ‘Outdoor Digital Art Gallery’ shows mainly short films and ‘video art’ and is primarily sponsored by Target – the US retail clothing chain. Mark Bennett of Target described his company’s interest in building its image by aligning itself with ‘art’. Victory Square is an incredibly technically ambitious arrangement of eight screens mounted on two opposing walls of a retail centre, each wall supporting four 20 metre by 30 metre screens, each of which can be independently manoeuvred on sets of rails into a variety of configurations. However, although it is hard to imagine moving image work which lends itself to such manoeuvres without having been produced specifically for it, Victory Media only buys in work and does not actually commission artists. In fact the only art actually commissioned for this multiple screen site seems to be produced for Target itself – a series of 3D animations of marbles and butterflies designed to slip across the precisely choreographed screens, branded in the company’s red and white livery and given such titles as ‘Art Evokes’ and ‘Art Connects’ (see http://www.mefeedia.com/entry/target-art-evokes/3850160/).

Image: Victory Media Network screens in Victory Square, Dallas, Texas The screen in Federation Square in Melbourne charges rent to business residents that benefit from increased traffic and attention brought to that area. Michelle Cotton and Mark Aerial Waller work as curators who ‘publicise contemporary art’ by showing video art on a nine metre wide screen on top of the Marmara Pera Hotel in Istanbul that has been withdrawn from commercial use. All of these strategies depend on the changeable perceptions of cultural policy makers, the priorities of sponsors, or, as yet untested suppositions about commercial viability and public benefit. There is nothing like a recognisable ‘business model’ here. You also start to wonder if the producers and policy makers ever come down to view how well their screens and its contents actually work with its intended audience. (No one is going to stand around in front of a screen shouting into their mobile phones in order to inch critters around a game board – as in the highly lauded ‘MegaPhone’ game). It is as though these giant TV’s are in turn controlled by giants who are too high up to know what things look like from the ground. Instead, the development of an urban screens policy has become such a game of political football that it was impossible to even begin discussing how such a collision of interests could come together to create cultural opportunities out of this new medium. One can immediately identify several assumptions that have been made about the practical placement of large scale urban screens that indicate a certain narrowness of perspective. A quick look at the three screens that formed the backbone of the public exhibition in Manchester revealed just how much their success will depend on the art of their location, positioning and scheduling. For instance, the ‘original’ BBC Big Screen in Exchange Square is perched high above the main façade of shops, its remoteness according it no more significance than the other visual displays that typically saturate the retail precincts of a town centre. In order to function as a focus of national events they must be placed like public monuments towering above people in the middle of town squares. But this also means that at other times it is difficult for them to take on other roles – they recede into just another animated billboard, waiting until such time that David Dimbleby reappears and invites us to witness a royal wedding. This is why spectators always have to be organised to watch this screen through programmed events (most of the time football matches) instead of just stumbling across it.

Image: Victory Media Network screens in Victory Square, Dallas, Texas The screen in Federation Square in Melbourne charges rent to business residents that benefit from increased traffic and attention brought to that area. Michelle Cotton and Mark Aerial Waller work as curators who ‘publicise contemporary art’ by showing video art on a nine metre wide screen on top of the Marmara Pera Hotel in Istanbul that has been withdrawn from commercial use. All of these strategies depend on the changeable perceptions of cultural policy makers, the priorities of sponsors, or, as yet untested suppositions about commercial viability and public benefit. There is nothing like a recognisable ‘business model’ here. You also start to wonder if the producers and policy makers ever come down to view how well their screens and its contents actually work with its intended audience. (No one is going to stand around in front of a screen shouting into their mobile phones in order to inch critters around a game board – as in the highly lauded ‘MegaPhone’ game). It is as though these giant TV’s are in turn controlled by giants who are too high up to know what things look like from the ground. Instead, the development of an urban screens policy has become such a game of political football that it was impossible to even begin discussing how such a collision of interests could come together to create cultural opportunities out of this new medium. One can immediately identify several assumptions that have been made about the practical placement of large scale urban screens that indicate a certain narrowness of perspective. A quick look at the three screens that formed the backbone of the public exhibition in Manchester revealed just how much their success will depend on the art of their location, positioning and scheduling. For instance, the ‘original’ BBC Big Screen in Exchange Square is perched high above the main façade of shops, its remoteness according it no more significance than the other visual displays that typically saturate the retail precincts of a town centre. In order to function as a focus of national events they must be placed like public monuments towering above people in the middle of town squares. But this also means that at other times it is difficult for them to take on other roles – they recede into just another animated billboard, waiting until such time that David Dimbleby reappears and invites us to witness a royal wedding. This is why spectators always have to be organised to watch this screen through programmed events (most of the time football matches) instead of just stumbling across it.

Image: Rude Architecture, Chat Stops Another good example of how this physical positioning leads to what we might call a particular ‘mode of address’ and also moves towards a new encounter with the screens' relations of production was one of the interactive works displayed at Cathedral Gardens, Peter Aerchmann’s Augenblicke. This consisted of an image of a small crowd of life sized people turned away from the viewer, perhaps inviting you to join them in observing something that their backs simultaneously obscured. If you moved a little closer your intrusion was detected by a nearby camera, causing them to spin around and confront you. Very quickly I found myself trying to run at the screen to see how far I could get before the animated crowd scattered, as though playing a game of ten pin bowling with human skittles. After nearly bumping into the screen itself, I found myself peering at the grid of individual LED lights. Each one was the size of a pea yet separated from each other by surprisingly wide intervals, and suddenly difficult to reconcile with the seamless motion of the video image.

Image: Rude Architecture, Chat Stops Another good example of how this physical positioning leads to what we might call a particular ‘mode of address’ and also moves towards a new encounter with the screens' relations of production was one of the interactive works displayed at Cathedral Gardens, Peter Aerchmann’s Augenblicke. This consisted of an image of a small crowd of life sized people turned away from the viewer, perhaps inviting you to join them in observing something that their backs simultaneously obscured. If you moved a little closer your intrusion was detected by a nearby camera, causing them to spin around and confront you. Very quickly I found myself trying to run at the screen to see how far I could get before the animated crowd scattered, as though playing a game of ten pin bowling with human skittles. After nearly bumping into the screen itself, I found myself peering at the grid of individual LED lights. Each one was the size of a pea yet separated from each other by surprisingly wide intervals, and suddenly difficult to reconcile with the seamless motion of the video image.

Richard Wright <richard AT futurenatural.net> is currently working on ‘decorative surveillance’ – a live video project that uses the flow of people through designed public spaces as an animation tool. He is also researching a book exploring the contemporary practice of animated media

Info

Urban Screens Manchester 07Conference, 11 – 12 October 2007. Art and Events, 11 – 14 October 2007. Held at Manchester Town Hall and Cornerhouse, Manchester.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com