Future Face

The Science Museum’s Future Face exhibition claimed to provide a critical take on the culture of superficiality. Laura Sullivan visits and finds in the mirror world of cosmetics, masks and digital image manipulation a reflection of the society of control

> Michael Najjar, Dana_2.2, 1999-2000

> Michael Najjar, Dana_2.2, 1999-2000

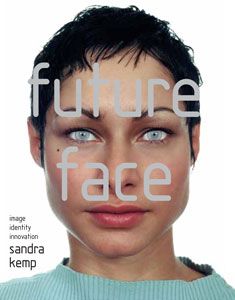

The Science Museum’s recent exhibition Future Face gathers an impressive array of images and artifacts and asks compelling questions about this culturally important and visually ubiquitous part of the body. However, Future Face rarely provides answers to such questions and ultimately suffers from a schizophrenia and superficiality all too common in museum exhibitions aimed at mainstream audiences. Given the popularity of the ‘face’ as a topic as well as the current fascination with many of the themes the exhibition highlights, such as surgical makeovers and digital image manipulation, one has to wonder why the curator, visual culture researcher Sandra Kemp, didn’t aim for more depth, focus, and coherent presentation. As the opening textual panel explains; ‘Future Face presents a rich mix of material from anatomy, portraiture, forensics, medicine and popular culture from prehistory to the present day’. The exhibition’s title notwithstanding, this temporal range is coupled with an equally expansive topical scope, as evidenced by the introductory texts for each of the exhibition’s six sections. Future Face introduces the exhibitions’ thematic concerns of the relationship between the face and identity; emotions expressed via the face; artistic and scientific efforts to understand and portray the face; anatomical and biomedical approaches to the face; and moral values attached to the face. ‘What is the face?’ investigates the physical structure of the face in addition to evolutionary aspects of the face’s shape and facial expressions. ‘Why do we conceal faces?’ features theatrical, ritual, torture, and social masks. ‘What are the limits of the face?’ examines facial surgery and prostheses, in their historical, present, and future guises. ‘How do we interpret faces?’ investigates the development of portraiture and the role of facial recognition and biometrics in immigration policies and crime-fighting efforts. The final section, ‘What is the future face?’ looks at examples of media and digital faces. Analytical connections and conclusions are sacrificed for such breadth; any one of the section topics could comprise its own exhibition. Granted, people who want a more fleshed out examination of the topics provoked in the exhibition can consult the snazzy CD-ROM and book, accompanying texts available for purchase. A series of talks as well as the 19-21 November 2004 weekend of ‘The Face on Film’ at the Curzon Mayfair provided chances for more in-depth considerations of the issues raised by Future Face. Yet my initial dissatisfaction with the exhibition was only somewhat alleviated by those live experiences, as well as by the accompanying digital and printed texts.

As my academic research focuses on cosmetics advertisements and the discourse of beauty, I came to the exhibition with a particular interest in gender-related aspects of the topic, and in this regard I was especially surprised and frustrated. The exhibition’s text concerning developments in cosmetic and reconstructive surgery never mentions gender (or race, for that matter). There are elements related to historical pressures on women to conform to rigid standards of appearance, such as the photographs of Max Factor’s 1932 ‘Beauty Calibrator’ and Helena Rubinstein’s ‘Pomade Noir Masques’ featured in advertisements from 1939 British Vogue, yet these images are presently in entirely decontextualised fashion. In the companion book, when Kemp matter-of-factly claims that “The human eye looks for and can detect the slightest deviation from the accepted norm in another’s face”, she not only perpetuates a suspect biological determinism but also neglects to consider how the ‘accepted norms’ in relation to human faces are intricately tied up with sexism, as well as with the gendered nature of the whole relationship between visuality and the face. This can be said equally from times when paintings and photographs of people became popular, to the current avalanche of advertising and media images of faces, where female faces and bodies are used to sell every kind of product under the sun. That Kemp neglects to acknowledge or cite any of the studies that link the socialisation process and exposure to such volumes of particular kinds of facial images to people’s expressed preferences reflects this overall neglect of gender as well as a predilection for reporting the findings of ‘science’ or ‘research’ as fact. Similarly, in her discussion of the £225 million a year that Britons spend on cosmetic surgery, Kemp notes that “It is one of the most common reasons given by women for non-property loans”, yet, incredibly, she does not remark upon this statistic or what it reveals about the lengths to which women who have internalised dominant and sexist standards of beauty will go to try to achieve them, even going into debt for such surgical modifications.

Jo Longhurst, Terence, 2003 > ......................................................................

Jo Longhurst, Terence, 2003 > ......................................................................

The accompanying CD-ROM includes an interactive exercise for viewers to categorise faces as belonging to males or females. Discerning gender becomes a ‘fun’ activity, belying the biological determinism and heterosexism characterising much of Future Face, including this game. The exhibition asks, ‘What is the difference between male and female faces?’ neglecting to acknowledge the constructedness of such categories, much less the ambiguity and androgyny characterising most people’s bodies and faces. Of course, transgender is nowhere in this landscape, in which everyone is neatly divided into ‘male’ and ‘female’ and where such states are based upon innate physical characteristics. We are told that when hairstyle and facial hair are stripped away from images of faces, ‘Some of the most informative measurements’ that enable people to accurately discern gender ‘include those of the eyebrows and nose’; ‘The male face has a more protuberant brow, with bushy eyebrows which are more extensive than the female’s’. The performativity invoked by theorists such as Judith Butler is absent in such equations, with no awareness that some lesbians, for example, intentionally eschew the cultivation of a ‘feminine’ appearance. (Women of any sexual orientation, for that matter, might possess bushy eyebrows and decide to leave them that way.) Future Face also asserts that ‘The distance between the eyebrows and eyes seems to be a very strong cue for distinguishing male from female faces’. Such proclamations make me want to recommend that Kemp and colleagues get a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, fast, as they seem to be unaware of the social nature of vision and visual preferences. If the computer is a ‘cool’ way to produce images of faces minus their obviously gendered features and enables an interactive setting for viewers to ‘choose’ whether each face belongs to a male or female, digital technology is also fetishised for its capacity to create avatars (such as Lara Croft) and digital models. While Kemp decries the trend towards ‘perfectionism’ and adherence to ‘standard ideas of beauty’ in technofaces, there is no critique of the sexism prevalent in these developments.

Sexism and women’s issues in general were more overtly on the agenda at one of the supplementary talks I attended at the Dana Centre on 2 December 2004, an evening entitled ‘Is Beauty Skin Deep?’ that asked ‘Do cosmetics really deliver on their promises or is pseudo-science taking over?’ University of Manchester Professor of Dermatology Chris Griffiths outlined the primary causes of aging (exposure to sun and smoking) and explained the science behind skin care products, which only work on the skin’s surface, rather than on the subcutaneous layer that reveals signs of aging. Paul Crawford from the Cosmetics, Toiletries, and Perfume Association (CTPA) emphasised the ‘successful’ safety record of this UK regulatory body, particularly proud of the low number of complaints about false claims of advertisements of skin care products. After referencing the sexist, racist, and classist aspects of cosmetics use and beauty standards, past and present, Good Housekeeping beauty editor Vicci Bentley lamely ended with an address of the ‘million-dollar question: what really works?’. Finally, an executive director of Lancôme, Liz Mearing, used her time to promote the company’s latest techno-flashy sales gizmo (with a typically cryptic and pretentious name: Diagrîos). The machine, Mearing said without irony, ‘is the tool of expertise excellence at point of sale to increase beauty consultant credibility’. One camera magnifies the customer’s skin by 60 times, to measure and reveal pore size, age spots, and oil content. The other camera, with 10X magnification, measures the depth and length of wrinkles. The resulting data is compared to ‘healthy skin’ of the same age group and printed out in a nifty graph which shows which products are needed to ‘correct’ the woman’s skin ‘problems’ and ‘abnormalities’. I wasn’t surprised by the composition of the panel nor by their complicity with dominant ideology about cosmetics, not to mention their allegiance to the multi-billion-pound skin care industry. What was fascinating and unexpected, however, was the more politicised turn of the q-and-a. My opening question about the ubiquity and dangers of petrochemical ingredients in skin care products, was deftly dodged by CTPA rep. Crawford and dermatology Prof. Griffiths. Yet every questioner after me kept asking more about these ingredients, often bringing in more scientific knowledge than the ‘expert’ speakers themselves possessed (e.g., the poisonous nature of ubiquitous ingredient, sodium lauryl sulfate). Clearly flustered, the panelists ultimately responded that they didn’t know what the women questioners were talking about. Another woman further upset the applecart by bringing up the huge profits of the cosmetics companies, which the speakers were also at odds to deny. Nonetheless, this presentation revealed the investment of the whole enterprise in the profit-seeking basis of technoscientifically informed efforts related to the face, cosmetic or otherwise; the exhibition, we should remember, is after all sponsored by the Wellcome Institute, an independent charity, originally endowed by a pharmaceutical company.

The Future Face’s naive excitement about flashy technoscience means that crucial lines are blurred, with videos celebrating breakthroughs in cosmetic surgeries to repair ‘disfigurements’ and equally valourising elective surgeries to change our faces. Moreover, a fetishisation of ‘choice’ is promoted. Unbelievably, Kemp opens the book’s section on the ‘new face’ by quoting one of the cosmetic surgeon characters from the popular television series Nip/Tuck:

'"Tell me what you don’t like about yourself"' is the surgeon’s catchphrase from Nip/Tuck, the US televisionsatire. Sean McNamara, the program’s fictional surgeon, argues: "To succeed these days you need confidence and self-esteem. If you can change a face and change the way someone feels about themselves, that’s very satisfying. It’s a good thing that we’re moving towards a society in which the ways of improving life are available, be it health, life expectancy or, yes, one’s looks. Soon the cosmetic surgeon will be regarded as no more than the GP of the aesthetic side of well-being."'

It is bad enough that the ‘opinion’ of a television character is cited with authority, but even worse, this quotation goes unremarked upon; there is no irony to its presentation; and no segue into the historical overview Kemp undertakes next is provided. As a result, the implication is that ‘McNamara’ is right, that cosmetic surgery to make folks feel better is desirable, ‘a good thing.’

Elsewhere Future Face is conflicted about the question of biological determinism. Speaking about the notorious 2003 image of Michael Jackson’s ‘mug-shot’, she acknowledges that ‘Race is one of the many ways in which we attribute meaning to the face and the adoption of a new or different cultural facial style is a powerful indication that the face is not universal’. However, this critique of universalism is belied in other passages, for instance when Kemp describes and promotes Darwin’s ideas that facial ‘expressions are innate rather than learned behavior’. Kemp supports the idea that beauty preferences are biological and universal; at one point, she claims: ‘From the moment they are born, babies appear to be hard-wired to look at faces and they very quickly learn to recognise them. Throughout life, adults are drawn to faces with the characteristics of babies and small children, perhaps evidence of an instinct to protect the young and vulnerable. Faces with worldwide popular appeal are often baby-like’. This passage introduces a discussion of the popularity of Disney’s Mickey Mouse character. Seriously. The exhibition’s universalising logic is explicit; one intro panel insists: ‘[T]here is remarkable consensus about what makes a beautiful face. From ancient Greece to the modern day, the classification of the beautiful and “good” face has been based on balance and symmetry, despite wide differences between individuals and cultures as to what is considered physically attractive’. The next sentence would seem to acknowledge the contingent status of beauty standards -- ‘Is there, however, a growing trend to increasingly link what is beautiful with what is “good” or “acceptable” with negative consequences for those of us who do not fit the norms?’ -- yet other claims undercut this recognition. Kemp asserts that ‘Recent research suggests that we are genetically programmed to prefer symmetrical faces’ and even cites the opinion of evolutionary psychologist Steven Gangestad, who outlandishly declares that ‘Symmetry alone explains why Elizabeth Taylor, Denzel Washington and Queen Nefertiti are universally recognised as beautiful’. Actually, even mainstream women’s fashion magazines demonstrate the falseness of this view, for example featuring images of ‘supermodels’ in which one side of their faces has been doubled to show a lack of symmetry, the resulting computer-generated photographs displaying faces that would be classified as ‘not beautiful’ according to dominant standards.

Each of the exhibition’s brief introductions concludes with a series of simple, tantalising questions, yet politically salient issues and critiques are bracketed. For example, although the ‘How do we interpret faces?’ section includes descriptions of U.S. biometric data collection and U.K. trial introductions of universal ID cards, the text ends with a more narrowly framed and less politically controversial question: ‘And how accurately can we identify people we have seen commit crimes?’. Amongst images of criminal ID cards from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, one 1914 photograph is illuminating and hilarious; after a ‘refined’ woman attacked a portrait of Thomas Carlyle with a butcher knife, ‘in an effort to protect the gallery’s collection from further attacks, idenitification portraits of “known militant suffragettes” together with their typed descriptions were issued by the police and distributed to the National Portrait Gallery’s attendants’. In the exhibition, critique of current criminalisation issues associated with images of faces is non-existent. Psychology professor Vicki Bruce authored the accompanying book’s closing essay and was also the featured presenter at another complementary event I attended, speaking in ‘The Face on Film’ weekend’s session on ‘Surveillance, Political Identity, and the Face’. Both in her talk and essay, Bruce problematised the processes of facial recall and identification. Moreover Bruce, unlike Kemp, points to the ‘big brother’ aspect of current developments in surveillance technology, and gestures towards the links between such efforts and identity-based oppressions such as sexism and racism, issues also elided entirely by the exhibition and Kemp’s essays. Kemp, in contrast, presents dominant ideology as fact, claiming, for example, that ‘global terrorism and illegal immigration have increased the drive to introduce ID security technologies based on biometric data’, as if it is not in actuality governments and people in power who have increased such a drive.

> Digital Celebrity Productions, Digital MarleneThe exhibition is also ideologically conflicted about class and economic dynamics, for example in its simultaneous questioning and valourisation of the role of celebrity culture. Michael Jackson’s ‘mug-shot’ is displayed to problematise glamorous images of celebrities to some extent. And Kemp explains that ‘The cult of celebrity images is ultimately just as dependent on social stereotypes as any of the physiognomic portraits of the last century have been’. Yet in both the exhibition and the book, Kemp implicitly endorses commodification of celebrity faces and images, uncritically relaying that one of the exhibition’s digital pieces, ‘The hauntingly beautiful Digital Marlene [as in Marlene Dietrich] was created by digital animator Daniel Robichaud for Virtual Celebrity Productions, now the licensing and merchandising company Global Icons, which aims to “help celebrities protect and extend themselves as brands”’!

> Digital Celebrity Productions, Digital MarleneThe exhibition is also ideologically conflicted about class and economic dynamics, for example in its simultaneous questioning and valourisation of the role of celebrity culture. Michael Jackson’s ‘mug-shot’ is displayed to problematise glamorous images of celebrities to some extent. And Kemp explains that ‘The cult of celebrity images is ultimately just as dependent on social stereotypes as any of the physiognomic portraits of the last century have been’. Yet in both the exhibition and the book, Kemp implicitly endorses commodification of celebrity faces and images, uncritically relaying that one of the exhibition’s digital pieces, ‘The hauntingly beautiful Digital Marlene [as in Marlene Dietrich] was created by digital animator Daniel Robichaud for Virtual Celebrity Productions, now the licensing and merchandising company Global Icons, which aims to “help celebrities protect and extend themselves as brands”’!

Having articulated many of the aspects of the exhibition I find ideologically and politically problematic, I should also say that it features many moving, fascinating, and provocative images and artistic pieces. I have to admit I played with the ‘Micro-Expression Training Tool’ (METI) for quite a while. Designed by psychology professor Paul Ekman, the machine features photographs of people’s faces; a button pushed gives a quick flash of the person’s ‘micro-expression’ before returning to ‘normal’. Ekman defines ‘micro-expressions’ as ‘very fast facial movements lasting less than one-fifth of a second’ and claims that they ‘are one important source of leakage, revealing an emotion a person is trying to conceal’. Using a computer keyboard, the viewer gets a chance to guess which emotion the micro-expression reflects, before being given the ‘correct’ answer. I got a kick out of guessing these ‘concealed’ emotions correctly, until I read the sidebar explaining that this tool is ‘used by police forces around the world’.

> Catharine Ikam and Louis Fleri, Elle, 1999

> Catharine Ikam and Louis Fleri, Elle, 1999

Some of the digital art installations are seductive, such as Elle, produced by Catherine Ikam and Louis Fleri, a ‘virtual head’ of an Asian looking female in three dimensions, disturbing the viewer with its sole movement of blinking eyes and its subsequent revolutions showing the view of the ‘empty’ rear of the head, its face then only a mask. In the sidebar to Elle artist Ikam describes her visual texts of this type as ‘“protheses” to access “new architectures of perception”’ and claims that ‘In these works, the face is no longer a “record” but a “process”’ (provocative suggestions I would’ve enjoyed having elaborated more fully).

One piece, commissioned especially for this exhibition, blew me away. 15 Seconds by Christian Dorley-Brown consists of side-by-side video clips of people, the first filmed at age 10 in 1994; the second a decade later. Participants were instructed to communicate to the camera only via facial expression. As Kemp notes, ‘This on-going project is an eye-opening social documentary and an elegiac meditation on the passage of time and the loss of childhood innocence’. The resulting differences in each pair of images are startling and hugely revealing. The ten year olds move a lot, make faces, engage in play, giggle, and are quite animated. The twenty year olds are almost entirely still, holding their expressions for long periods, smiling in stony fashion, and, most heartbreaking of all, their eyes are filled with sadness. Never have I seen a silent video piece expose so much about how social dynamics wear down young people, stomping out all their spirit, emotionality, and hope. I stared at the compelling pairs of clips for ages.

However, despite captivating individual items like Dorley-Brown’s videos, the overall sense of the exhibition is of disconnected overload. It is unclear why some of the pieces are included or how they relate to others displayed, or even to the exhibition’s stated themes. A good example is One Man’s Land by Heather Barnett (2002), plopped into the middle of the hand mirror piece. Described as ‘a contour map of a young man’s face etched into steel’ using land-imaging 3-D mapping technologies, it seems gimmicky and out of place. I presume that other attendees, like me, look for patterns and relationships amongst the material exhibited, and in this respect Future Face is most frustrating. It is hard to figure out how a Benetton image of a ‘black’ Queen Elizabeth relates to photographs of folks with ‘disfigured’ faces, or how criminal ID composites mesh with the Chris Cunningham 1999 Bjork video ‘All is Full of Love’ featuring robots kissing, or with the huge photograph of David Beckham with a chip implanted in his forehead. Overall, I could only enjoy bits and pieces of the exhibition and accompanying CD and book in decontextualised fashion. I did learn a lot, finding in many of Kemp’s exhibition images and textual descriptions fascinating facts and anecdotes, such as the history of reconstructive surgery connected to the first World War due to the massive amount of facial injuries incurred in trench warfare. I had never heard about the tin masks and other prostheses used for these injuries, and I was shocked to hear about the ‘horror and disgust’ directed at men who had such injuries, to the degree that ‘Benches on the road into Sidcup were painted blue to warn local residents that the men sitting on them might have a disturbing appearance’! I was enlightened about the history of portraiture, and especially intrigued by the cartes de visite developed in the 1860s (‘low-cost miniature portraits, containing three or four poses fitted to a single glass negative and supplied in bulk’ and ‘exchanged and circulated throughout society’) and the decorative facial masks popular with members of the upper class in the ‘high society’ circles of the early twentieth century. Generally, the social and political contextualisations provided for the historical overviews of artistic, anthropological, and psychological considerations of the face were absent from the examinations of contemporary parallels. Overall, description substitutes for analysis. As a result, I’ve come away from the experience enlightened at the level of historical overview and in possession of some new and interesting statistics and facts, but left with key questions and a desire for the many dots of the Future Face to be connected more thoroughly.

Future Face was held at the Science Museum, London 1 October 2004 – 13 February 2005.

All quotations are from the exhibition literature and the book:

Future Face: Image, Identity, Innovation, Profile Books in association with the Wellcome Trust, 2004ISBN: 1 86197 768 9

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com