Fordism? Who's that For, Men Only?

'Double Negative Feedback' expresses the hope that the chaos unleashed by the cybernetic loops

Can popular cinema ever do justice to the complexity of social struggle? Noreen MacDowell gets under the bonnet of Made in Dagenham's portrayal of the Ford machinists' struggle for equal pay

Made in Dagenham is a well crafted, feel-good movie about a strike by women machinists in 1967 at the Ford factory. They not only made seat covers, but assembled complex pieces of car trim. It raises a host of questions about attempts to make popular cinema from a broadly leftist political perspective, and specifically about British feature films. It is not The Full Monty or Brassed Off - centre stage are working class women fighting with purpose for their rights - it's better than those films. But like Calendar Girls, Nigel Coles' previous film, it shares many of their faults: the way points are made in short scenes where we are expected to read the code; too much stereotyping; soft compromises and evasions (what really happened - part victory and part defeat - is glossed over in the interests of the film's upbeat ending which features a glamourised Barbara Castle, the then Employment Minister). This ending shares a certain tone with much of ‘British film' comedy.

What matters in judging Made in Dagenham is who the audience for a ‘popular' film is likely to be and its effect on that audience. A justification for it, as with Ken Loach's Land and Freedom (a film which also compromises on the truth), is that it is aimed at young people. In the case of Loach's film, the intention was to show younger people that Stalinism was not the only form of revolutionary politics. In the present film, the idea - positively subversive in the current period - is that going on strike is a legitimate and potentially effective way of improving wages and conditions at work.

Judging by the audience at the showing I saw, it is not attracting such a young ‘target' audience. Besides that, the ‘legitimacy' of striking as portrayed here is very much of its time, and there must be a degree of nostalgia in harking back to a period when this was so, and when there was a relatively sympathetic mass media. This is the easy going Britain of the first Harold Wilson government, when Trade Union leaders were familiar with Number 10 Downing Street. That things were about to change is touched on with the character of the Ford strikebreak expert sent in from the USA carrying the now familiar threat that Ford will up sticks and move production elsewhere. It is touched on, but then swallowed up by the Barbara Castle finale in which this unreal heroine is placed against Wilson's vacillating pragmatism. It was also a time when it was easier for a section of workers in a large manufacturing company to bring production as a whole to a standstill.

The film starts really well. This is the 1960s and the Ford working class men and women are not saints in boiler suits - this is not Ken Loach. Not cool dudes either, in the way they dance, but they are dancing to two great tracks of the time, Desmond Dekker's ‘The Israelites' and ‘Wooly Bully' by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs. Unfortunately this becomes something of a ‘point made', and instead it is the same people's slowly developing confidence from a starting point of feeling intimidated by bourgeois culture which then dominates. Nothing wrong in that. It's what happened to class relations at a psychic level at this time. It was 1968, after all, and this is expressed well in Sally Hawkins' fine central performance. But a roundedness of character is lost when this working class hedonism disappears from the film. Equally, in the interests of roundedness, it would have been good to have seen more of the sweatshop-like conditions of the sewing shop and, at the same time, how seriously skilled the work is. It is, after all, the combination of skilled work with gendered pay inequality which is the strike issue, but it's left to Sally Hawkins to tell the management how difficult the work is. Not that this isn't a subversive message, with its attack on the ingrained elitism in the hierarchies of labour, but the film needed to show more of the process, the skill and the intensity of labour. Pre-strike solidarity among the women is done via those hint-codes of so much modern cinema. They are, for example, quite prepared to cover for Jaime Winstone's character with modelling on her mind, and are uninhibited in talking sex, but once again you get the sense that another ‘point' has been ticked off. These are Essex women who know how to have the crack. Both the ‘point-making' and the stereotypes reminded me of 1970s agit-prop theatre. Then we told ourselves that we presented archetypes and that this was neo-Brechtian. Self-deception perhaps, but these were quick plays in trade union halls. The makers of this film are clearly aware of this tradition but it's not an ideal form for cinema in which tough subtlety is required for it to work.

From then on, my misgivings started to kick in as I saw a history I knew being rewritten. The crudity of presentation of the relationship of the women with the male Ford workers and trade union figures who are cartoon ‘sell-out' figures, hides the lie whereby a part victory/part defeat is turned into a euphoric victory.

Image: Striking machinists from the Ford plant in Dagenham at a women's conference at Friends House, Euston, 28 June 1968

The reality was that the women went on strike to get recognition for the skill of their work and get it upgraded with equal pay at this new skill pay level. They did not win the upgrade they wanted and received only 90 percent of the pay taken by men in the same skill level. It took another 16 years, when the women machinists at Ford Halewood (Liverpool) went on strike, to win the fight for their skill level to be recognised and upgraded. Even then (as John Bohana, formerly of the Ford Workers' Combine and Big Flame, has noted in Red Pepper) they did not get equal pay with the men in a similar grade.

In the film, Barbara Castle is not just glamourised by Miranda Richardson, but presented as the woman with the real power, dwarfing the strike leaders like a fairy godmother, and just as much the rebel as she defies her wimpish, British comedy cartoon civil servants. What she actually did of any relevance was to introduce an Equal Pay Act some two years later; an Act with no teeth, as the later Halewood strike showed, and with gendered equal pay still not achieved. In 2010, the pay gap for full time work now stands at 16.4 percent. For a brief period of time before the capitalist offensive began in the mid '70s, pay differentials were used to increase wages generally in a perpetual process of ‘leapfrogging'. Given the strength of trade unions at the time, it was a mistake not to argue for gendered equal pay. Now however, when management across public and private sectors are on the offensive and trade unions relatively weak, equal pay demands have become a rationale for decreasing male wages.

A popular film - and I'm all for popular films if they achieve popularity - cannot get too tied up in the complexities of negotiations, but simplification can make for deception. 1968 saw not just the mass uprising in France - though its psychic impact elsewhere should not be underestimated - but was also marked by the emergence of a Women's Movement in this country. It was also a time when employment patterns were starting to shift towards a service sector in need of women, and coincided with the idea of the man as the sole ‘breadwinner' losing credibility. The insult aimed at the women in this film - that they were working for mere ‘pin money' - flies in the face of the soon to be pervasive reality that the working family would need two wages to survive.

There has been some public debate about the real role played by Bob Hoskins' shop steward character. Whatever the rights and wrongs, he is too much of an initiator - the behind the scenes pusher of the strike, just as there were actually many more leaders of the strike and not just the composite Rita O'Grady played by Sally Hawkins. Worse still, it is left to Hoskins' shop steward to most clearly articulate the virtue and necessity of equal pay, and to do so with a back story of his mother's struggles. This scene also includes a trading of quotes from Marx with one of the exaggeratedly awful union officials.

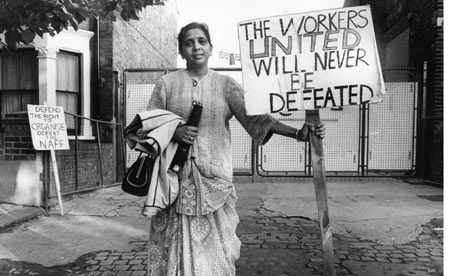

Image: Mrs Jayaben Desai, treasurer of the Grunwicks strike committee, 23 August 1977

What actually happened is that the men working at Ford who had initially backed the women's strike - in some cases their wives, sisters and lovers - withdrew their support as production came to a halt (revealing the importance of the women's work). It was also a time when they were involved in their own wide ranging, protracted negotiations. This was done with the belief that they set the benchmark for the whole working class. An out and out hostile attitude to the strike is made in a 15 second scene (point made). The more complex response (some men supported the strike, others didn't), is left to the husband of the Sally Hawkins character. It's a fine performance but he is lumbered with comedy clichés. You just know that left with looking after the kids he is going to make a mess of the cooking. Setting the frying pan on fire is a broad brush ‘point made'. Similarly the material hardship strikes entail is reduced to the repossession of the family fridge. And the one real argument the husband and wife have, when she says that he shouldn't need a pat on the back for supporting her, is too easily resolved. What's more, her sympathetic relationship with the wife of a Ford manager who doesn't take either of them seriously is too contrived to suggest how the nascent women's movement was given a push by women like the machinists at Ford.

Nine years after the strike there was a long, bitter struggle for union recognition by very brave women workers - many of them Asian - at Grunwick. Two years before Mrs Thatcher ever came to power, it was defeated because, although there was solidarity from men in Trade Unions, ‘We're here to support the lads', their support was gestural. Where it wasn't - the blacking of Grunwick's crucial postal traffic - the law and their own union joined a wholly unsympathetic media to come down hard on them. Gesture politics - like the mass demonstrations that only create a token stoppage by shutting out scab workers and deliveries, and then march off - do not take the situation and what is at stake seriously. These tokenistic displays ‘make a point' and then move on. I got a similar feeling from this film. If its purpose was to show the virtues and efficacy of collective action, these weaknesses ended up leaving it as an object of nostalgia.

Noreen MacDowell <noni51@hotmail.com> was a member of the Red Ladder theatre group in the 1970s before engaging in very different theatre with Oficina Samba in Portugal 1974-5 and then joining the Newsreel film collective which made two films about the Grunwick strike

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com