Fear of Fear Itself

This year’s Transmediale festival in Berlin was themed around the conceptual term ‘Conspire’. Here, Marina Vishmidt reviews its multiple presentations of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ collaborative truth production, and queries some suspicious absences

It's the Transmediale at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. Somewhere, something in this cavernous Marshall Plan edifice is flickering. Closer at hand in the exhibition hall, half-tilted black boxes on the floor solicit you to crawl under them and encounter others of your kind watching videos. The fauna underneath are warm and resistant, though you would expect to encounter something cold and slimy when lifting a rock, which is what the black-box bivouac viewing situation feels like.

Such thoughtful cues in the physical fabric of the exhibition mean it doesn't take long to cotton on to the data cloud of this year's festival: ‘Conspire’. This could at first be taken as a prim allusion to the still-unwieldy legacy of Stasi spookery in German social and political life, as well as contemporary control creep in our western security wings. However it is soon revealed as a far more gesamt curatorial narrative, extracting the Latin root of the word, 'con-spire' (to breathe with) in order to posit a truly ontological breadth to 'conspiracy' as a term with which to capture present-day global social realities.

Brian Holmes, Naeem Mohaiemen, Yassin Musharbash & Loretta Napoleoni on the Embedding Fear panel. Photo by Jonathan Gröger

Brian Holmes, Naeem Mohaiemen, Yassin Musharbash & Loretta Napoleoni on the Embedding Fear panel. Photo by Jonathan Gröger

The rest of the publicity statements seem to make a slightly factitious split between the ‘fear fetishism’ of conspiracy theory in its everyday, pacifying guise and an artistic, emancipatory gnosis of conspiracy theory as mode of knowledge. It thus begs the question of whether it pays to set 'conspiracy' as an ideology against the 'conspiracy' of critical inquiry in the first place, since surely the whole point of a concept like ideology is that it is immanent to real relations, and produces the 'real' which mediates these relations.[1]

It does make it clear, however, that the 2008 Transmediale is concerned to disinvest in the bad object, which it cites as the ‘obvious rhetoric of post 9/11 hysteria’, in order to clasp more firmly the good object, referred to by the phrase ‘the conspiratorial act as a strategic, creative and poetic collaboration’. Itself allegedly under a fog of displeasure from its Federal sponsors (although it was impossible for me to gain further clarity on this point), it was perhaps a populist inspiration to orient the festival away from the tangle of cables obligatory for media art festivals to such a high-alert trope for activists, theorists, artists and non-specialist audiences. Was this the hope of generating complicity through conspiracy? Although German current events have played along, regularly bubbling forth conspiracy in high places, from the repression of critical urbanist academics (as in the recent Andrej Holm case) to the dragnet of German executives stashing profits in Liechtensteinian moats.

With an extensive panoply of sessions in its discursive strand, accompanied in the auditorium by video projections of the simultaneous live chat, and an almost unimaginable host of performances, salons, installations, off-site events, site visits, public space interventions and the club_Transmediale, I can only present a vignette of what went on. In what may be a familiar attribute of media art and activism jamborees, the facilities providing for fiendish plot-hatching (panel discussions, workshops, salons) seemed on firmer ground than the ‘traditional’ format of the exhibition, whose raison d'etre seemed noticeably slighter, despite the ingenuity and coherence of several of the projects.

As any systemic analysis lays itself open to charges of 'conspiracy' by those of another ideological stripe, and because any intentionally organised array of objects in a cultural centre can judiciously be described as an art exhibition, the Transmediale seemed to pitch itself at a meta-level. It was possible to filter its broad thematic scope into every programming decision and into none of them per se.The exhibition and myriad of projects took an eclectic approach to 'conspiracy', whereas the panels mostly addressed different current and historical considerations about the security state, technologies of surveillance, and the esoteric roots of cultures of conspiracy. In two enticing-sounding sessions that I could not attend, panelists investigated the 'greying of the commons' as a pragmatics of anti-IP activity and famed Chilean socio-biologist Dr. Humberto Maturana spoke on 'co(i)nspiration', i.e. conversation and mimesis, as the bedrock of human development.

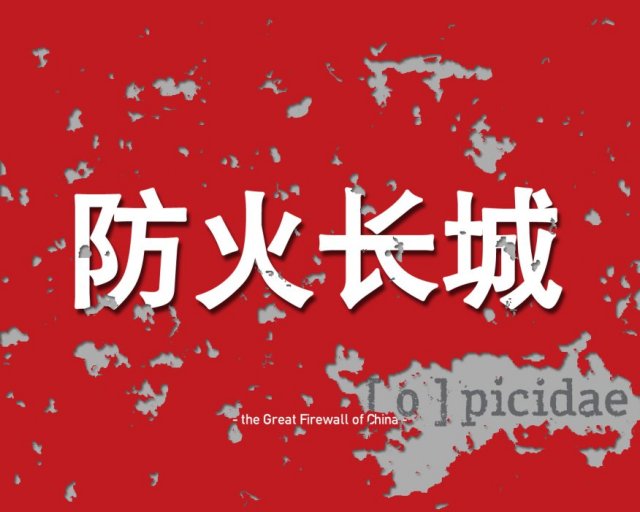

From the web project Picidae.net, Christoph Wachter & Mathias Jud

From the web project Picidae.net, Christoph Wachter & Mathias Jud

The notion that skepticism towards all-encompassing fear is the only sure way of tackling an uncertain future echoes Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous pronouncement, made in the midst of the Great Depression:‘The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.’ The parallels between then and the current financial meltdown are all too apparent. Yet, by conjuring a more or less ambient cosmic malaise as its target, the curators' choice of the rubric of 'conspiracy' did not take the opportunity to position Transmediale’s own remit in relation to state, sector and macro-economic goals that actuate its annual emergence. Also salient in this respect were the choices implicated in an unproblematised 'media arts' focus,nor were the distinctions and paradoxes of the included works placed under interrogation. Perhaps there was also a (missed) chance to elaborate a more acute and materialist diagnosis at the thematic level of the festival, rather than hazarding that particular projects or events might do so.

Such a diagnosis could level 'conspiracy' at a specific point, or a concatenation of points, which could extend into many trajectories, rather than hang suspended as a moody but nebulous atmosphere. For instance, if 'the production of fear' was one of the key strands of the event's discourse, then it could have been pinpointed as the production of fear by a crisis-ridden capital, with no other imaginative horizons to defuse antagonism than a surfeit of paranoia which acts as an economic engine when production has been eclipsed by speculation.

Of the two panel discussions I was able to attend, the first focused on Cybersyn ‒ the Chilean precursor to the Internet, devised by Stafford Beer to democratise the Chilean economy under Salvador Allende. What emerged from the detailed, reflective talks given by two Cybersyn project leaders, Fernando Flores and Raul Espejo, (the former also served as Allende's Minister of Economy), was that the project, for all its socialist ambitions, was able to distribute control, but not bolster autonomy, among the workers, bosses and bureaucrats in Chilean industry and services. An ambivalent set of developments which were brutally truncated by the coup. With supplements such as the beguilingly-named Cybernet (a network of telex machines to co-ordinate supply and demand) and Cyberstride (a real-time communications program), this still-anomalous use of cybernetics to foster rather than control social transformation aimed, in Espejo's words, to ‘reduce complexity and amplify capacity’. As he admitted, this was a tough brief to realise on the ground at the time, with class and workplace hierarchies coming back to haunt the drawing board. There was likewise a suggestion that the fortunes of the system were so closely bound up with those of Allende's government that once the latter was foiled by “geopolitical naiveté”, Cybersyn itself became a historical footnote, and its initiators imprisoned or exiled. Even today and even in Chile, it is a dead letter.

Later, panelist Alejandra Aravena presented her work with the Radio Numero Critico, a lesbian feminist radio station and online community portal, cataloguing the oppression of women, homosexuals and the indigenous in Chilean public life, but without making any reference to the historical experiments that had occupied the previous hour’s discussion. One was left wondering if this ommission was a matter of perceived irrelevance or a testimony to the completeness of Pinochet's victory. In sum, the brief glorious life of Cybersyn would seem to have yielded some lessons for the 'participatory technologies' of today, the most salient perhaps being that politics is the oxygen of technology, and that technological development can only advance the commodification of social life if social life is not organised to appropriate it for human ends.

Amazon Noir - The Big Book Crime, UBERMORGEN.COMThe second discussion was called Embedding Fear: The Internet and the Spectacle of Heightened Alert. Journalists Loretta Napoleoni and Yassin Musharbash, and artist Naeem Mohaiemen tackled the proliferation of fear as regulative idea and operational cost in what moderator Brian Holmes, radicalising Giddens, described as our contemporary, financialised 'risk societies'. The discussion circled around data profiling, Al-Qaida chat sites, journalistic objectivity, and the wholesale desolation of the public sphere until the artist and theorist Olga Goriunova asked a show-stopping question from the floor about the ontological basis of the politics of truth. The question, and Holmes' response, steeped in Foucault and linking political subjectivation to the social processes that construct truths, seemed to open another chink in the holographic thinking around the festival’s concept, namely that we can have our biopolitical spectacle and see through it at the same time. It would take an implicit commitment to some kind of politics of truth to engender the good and bad conspiratorial objects proposed by the festival; but the phantasmatic trope of conspiracy itself precluded ever revealing what that commitment was.

Amazon Noir - The Big Book Crime, UBERMORGEN.COMThe second discussion was called Embedding Fear: The Internet and the Spectacle of Heightened Alert. Journalists Loretta Napoleoni and Yassin Musharbash, and artist Naeem Mohaiemen tackled the proliferation of fear as regulative idea and operational cost in what moderator Brian Holmes, radicalising Giddens, described as our contemporary, financialised 'risk societies'. The discussion circled around data profiling, Al-Qaida chat sites, journalistic objectivity, and the wholesale desolation of the public sphere until the artist and theorist Olga Goriunova asked a show-stopping question from the floor about the ontological basis of the politics of truth. The question, and Holmes' response, steeped in Foucault and linking political subjectivation to the social processes that construct truths, seemed to open another chink in the holographic thinking around the festival’s concept, namely that we can have our biopolitical spectacle and see through it at the same time. It would take an implicit commitment to some kind of politics of truth to engender the good and bad conspiratorial objects proposed by the festival; but the phantasmatic trope of conspiracy itself precluded ever revealing what that commitment was.

However, if subjectivation is indeed the core issue, perhaps programmatic aims are the wrong places to be looking. In the cases where commissions and work in the exhibition succeeded, we might conjecture they conspired against the theme. Alexei Shulgin, Aristarkh Chernyshev and Roman Minaev's electroboutique: Media Art 2.0 proffered a deadpan reconciliation of the demands made by the market and critique on art production with its stall of gadgets conceived in the spirit of ‘crititainment’ (critical and entertaining). A droll manifesto underlined the non-conflictual goals of avant-garde art-into-life and consumer appeal (each item came with a limited warranty), while deprecating the star system of media art festivals. This system, the manifesto argued, thwarts democratic access to ‘useful inventions’, in distinction to the 20th century Modernists who paired industrial design with avant-garde ambitions and didn't mind getting their hands dirty in order to merge art and life. A further Modernist axiom, that of truth to materials, was signalled in the manifesto's poking fun at diamond-encrusted mobile phones and promoting an emphasis on 'visual interface' as the basic germ of electronic devices' social ubiquity. It was like Bauhaus 2.0, rendered in Shake image-compositing software. On a less whimsical note, there was the useful invention, and Transmediale Award nominee, picidae.net, a software which turns websites into images in order to circumvent web censorship. The project leaflet explained the etymology of Picidae (the family of climbing birds which the woodpecker belongs to, birds who peck holes in hard wood) and mused on the productive features of censorship:

Even direct censorship can yield some favorable results: from the class of correctors who check, apart from the ideological content, for various types of mistakes, contributing to the overall accuracy and preciseness of paper publications to strong counter reactions that give birth to the rich dissident cultures of resistance.This review was also written by the combined forces of repressive tolerance (the predictive feature of Open Office) and tolerant repression (spellcheck).

Wonder Beirut, Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil JoreigeThe film and video component of the festival was vast and thematically distinct to some degree and included Not a Matter of If But When by the Speculative Archive, whose elliptical treatment of the Lebanese conflict picked up the festival award and was echoed in the strong installation work by Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Wonder Beirut; and Bernard Mulliez's superb Art Security Service, a spoof that turned into a crusading documentary about the art-enabled class-cleansing of a Brussels shopping centre. Here you could watch architects say things like, ‘Once the character of the place changes, they [working-class café proprietors] may want to go somewhere else’; gallerists say things like, ‘It's immensely interesting to confront art with reality’; and the filmmaker, impersonating a security guard from the fictional ASS (Art Security Service) in order to film covertly, saying things like ‘I'm a guard for symbolic capital.’

Wonder Beirut, Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil JoreigeThe film and video component of the festival was vast and thematically distinct to some degree and included Not a Matter of If But When by the Speculative Archive, whose elliptical treatment of the Lebanese conflict picked up the festival award and was echoed in the strong installation work by Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, Wonder Beirut; and Bernard Mulliez's superb Art Security Service, a spoof that turned into a crusading documentary about the art-enabled class-cleansing of a Brussels shopping centre. Here you could watch architects say things like, ‘Once the character of the place changes, they [working-class café proprietors] may want to go somewhere else’; gallerists say things like, ‘It's immensely interesting to confront art with reality’; and the filmmaker, impersonating a security guard from the fictional ASS (Art Security Service) in order to film covertly, saying things like ‘I'm a guard for symbolic capital.’

The Transmediale exhibition was awash with heavily encoded, large graphic installations like the Societé Realiste’s spherical installation on 'coding' utopian movements, and Bureau d'Etude’s wall map. There were also a number of pieces that could not be said to be native to Transmediale's genre category, and would have settled easily into any other 'contemporary art' exhibition, like the Artur Żmijewski video, the photo archive presented by Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, and the photo documentation of Julius Koller and group actions. The Wonder Beirut photographic archive was a syntactically, historically and emotionally rich assemblage. This was the collection of a Beirut photographer who made a mint in scenic postcards before civil war settled on the capital, at which point he started modifying his postcards to reflect the damage those scenes had sustained. Like the 'dialectical [after]image', the daintily seared postcards are the inscription of multiple times on a present that cannot grasp them, dreaming as it is of things which the burn marks have effaced. The austerity of this frozen gesture did not quite resonate with anything else in the exhibition. Across the room, UBERMORGEN.COM have hooked a book up to wires in an incubator and called it Amazon Noir, ‘the illegitimate and premature son born from the relationship between Amazon and Copyright.’ Somewhere, something darts out from under a black box. But again, nothing holds this exhibition together but the institutional space between and around the pieces, um, processes. And that is not necessarily a drawback, since conspiracy is speculative, not definitive.

Since the infrastructures for the development of the 'digital culture' which the festival is dedicated to celebrating, and the military, financial, spectacular and bureaucratic means of producing and modulating (in)security are the same, perhaps we could think of this as a plein-air conspiracy. And that this, and the copious other festivals that celebrate 'digital culture' are eliding commodity aesthetics, managerial techniques and social innovation, all displaying a curious fidelity to a paleo-Modernist sacralisation of medium; the latter an always tenuous initiative which cannot fail to be interesting, if rarely genuinely startling.

Likewise, the proliferation and complexity of instruments of critique is always just a bit outflanked by the instruments of domination that create the conditions for it to flourish, especially when it’s technological mediation at issue and the reduction and brutality in social relations intensifies with the mediation of this brutality. Do the good and bad conspiracies proposed in the Transmediale curatorial fabric finally boil down to social technologies juxtaposed with the asocial technologies perpetuated by the market and the state?

If so, then the moral clarity underpinning the conspiracy genre is strikingly missing, for such a schema cannot hide its profound ambivalence and imbrication, if applied to federal and coporate-supported media arts festivals. But this has always been the limited utility of the conspiracy paradigm which transmutes politics into dogmatic morality plays, where the 'last instance' is diabolic rather than economic, and diminishing returns ensue on every instance of decoding. Meanwhile, The Haus der Kulturen der Welt provides a stage for an ethnographic museum of the future, if the museum of the future can be defined simply by the electricity needs of its artefacts. Outside, the stealthy encroachment of ap's Moving Forest hack of Kurosawa's Macbeth is underway, further tainting the festival's cognitive map of exhibitable objects and mobile processes. A sonic performance, Moving Forest applies public wi-fi and mobile technology to distend the 12-minute final 'moving forest' sequence into a 12-hour, 5-act performance in Berlin city space. As the Moving Forest synopsis in the guidebook also concludes, ‘The conspiracy returns and thus remains. The grey castle remains.’

Marina Vishmidt <maviss AT gmail.com> is mainly a writer based in the Theory Department of the Jan van Eyck Academie. Her work focuses on the production of temporality, labour and value in contemporary art practice, politics and economics. She has written for Mute, Chto Delat?, Framework, and Moscow Art Magazine, and lectures and teaches at the Jan van Eyck, the Van Abbemuseum and the Rietveld Academy. She edited Media Mutandis. A NODE. London Reader and has recently published the essay 'Line Describing a Curb: Asymptotes about Valie EXPORT, the New Urbanism and Contemporary Art' in Art and Social Change: A Critical Reader, Charles Esche and Will Bradley, eds., Afterall and Tate Publishing, London, 2007

Footnotes

[1] 'Etienne Balibar has argued that Marx’s critique of ideology in The German Ideology has as its corollary a concept of the 'real as relation'. The specific quote is: 'The materialist critique of ideology, for its part corresponds to the analysis of the real as relation, as a structure of practical relations.' As Balibar notes, Marx does not just denounce ideology in the name of the actually existing material relations of production, in which case the relations would be the truth of the fiction of ideology, but attempts to demonstrate how ideology emerges through those relations, constituted by the division between mental and manual labor. Thus, it is not possible to simply juxtapose an ideological conception to a real condition since that real condition, the structure of material relations of production and reproduction, includes ideology.' taken from the Unemployed Negativity blog, 23 February 2008, http://unemployednegativity.blogspot.com/2008/02/real-as-relation.html

Info

transmediale.08 CONSPIRE: conference, 29 January – 3 February ‘08; exhibition, 29 January – 24 February; http://www.transmediale.de

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com