Exhausted States

Concluding their three-part exchange for Mute, artist Alfredo Jaar and philosopher Simon Critchley contemplate how to keep on, artistically and politically, in the face of the spectacular violence that washed-up liberal democracy meets with daily indifference. This exchange was convened by David Morris

The conversation continues from where it left off last time, with Simon Critchley reflecting on the idea of the ‘supreme fiction', ‘a fiction in which we can believe':

...the question of the supreme fiction might be linked back to forms of political association that have been figured in the last months in all their hopeful, resistant complexity. I see the question of radical politics as also animated by the question of the supreme fiction. Forgive me if I'm not clear, I'm still figuring out what I think as I write.

Alfredo Jaar, 18 April 2011:

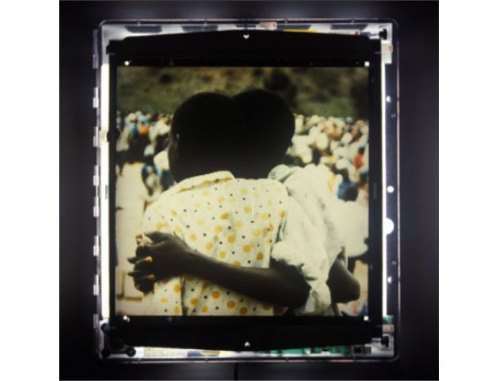

I forgive you, dear Simon, as I suffer the same problem, in a much more acute way than you do, I am certain. In your book on Wallace Stevens you asked us to ‘overcome epistemology', and you called epistemology the central area of philosophy. Not only do I agree with you but I think it is also a fundamental area of art, perhaps one of the central problems we face in our practice as artists. Because I believe that art is communication, communication requires a language, and language requires a vocabulary. Artists are limited not by imagination, which can be infinite, but by language, which is finite. That supreme fiction you are talking about is a product both of the imagination and the capacity of language to articulate it, to allow it to exist. And in my view, that supreme fiction, in order to work, requires imperatively a new language. As I believe our daily language is corrupted, disassociated from the truth. It was Blake who suggested that in order not to be enslaved by another man's system we must create our own system. I became an artist because I believed that in the realm of art I could create my own system, invent my own language. Create a new vocabulary of truth. Of course I have failed, miserably, but I have tried hard. I was condemned to fail, I am afraid. What is the truth of a genocide that claimed a million lives in Rwanda? What is the truth of the criminal indifference of the so-called world community? Is there an existing vocabulary to express that?

Image: Cover of Alfredo Jaar's Let There be Light: The Rwanda Project: 1994-1998

That is perhaps why I find refuge in poetry, from Ungaretti to Pasolini, from Cioran to Akhmatova, to name just a few.

This is Anna Akhmatova in Requiem:

So much to do today:

kill memory, kill pain,

turn heart into a stone,

and yet prepare to live again.

Earlier in that poem, she tells the story of spending 17 months in the visitors' waiting line of the Leningrad prison. One day a woman whispered into her ear: ‘And can you describe this?', ‘Yes, I can,' she answered. Well, we can and we must. However difficult it is. And it is difficult.

When you see the question of radical politics as also animated by the question of the supreme fiction, I could not agree more. It is precisely in the depressing lack of imagination that radical politics have failed us. And continue to fail us to this day, at least here, in this country. It is perhaps the reason why we have been swept away by the events in the Middle East, because we simply could not have imagined it using our existing political language. Because our generation has not been able to affect change the way it is happening now in Egypt or Tunisia or Libya. Even when faced with conditions infinitely less demanding than theirs. What do we call this failure?

I returned this morning from Helsinki where, last night, in Finland's general election, an ultra-nationalist, anti-immigration party captured 19 percent of the votes, meaning nearly a fifth of the electorate. They call themselves the True Finns. A Tampere University political analyst told the AFP news agency that the election outcome was astonishing: ‘The True Finns' victory, surpassing every poll and every expectation of a drop on election day... plus the total collapse of the Centre - the whole thing is historic,' he said. It is well known that ultra-nationalists have infiltrated the True Finns, as some of the party's candidates belong to Suomen Sisu, a xenophobic group that declares openly that ‘different ethnicities should not be intentionally mixed in the name of multiculturalism.' In the European Parliament, the True Finns form part of a group named Europe of Freedom and Democracy, which includes parties such as the Independence Party from the UK and Italy's Northern League. The True Finns are not alone, my dear Simon. I will not depress you with a full listing of parties like these in Europe.

It is Cioran that has captured best my state of mind in times like these. He wrote:

A feeling of emptiness grows in me; it infiltrates my body like a light and impalpable fluid. In its progress, like a dilation into infinity, I perceive the mysterious presence of the most contradictory feelings ever to inhabit a human soul. I am simultaneously happy and unhappy, exalted and depressed, overcome by both pleasure and despair in the most contradictory harmonies.

At moments like these, poetry offers air, a breathing space. We are the embodiment of that ‘contradictory harmony', it is in its impossible logic that we move through this world and grasp some air, wherever we can, sometimes in the wrong places.

Simon Critchley, April 30/May 7 2011:

I know that emptiness and I too find a refuge in poetry.

But I also see something else. Some other possibility.

Let me explain. There is a motivational deficit in liberal democracy, an increasing weariness, drift and disinterest in the institutions, habits and practices of liberal democracy. This is leading to an increasing disintegration of ‘normal' state or governmental politics. In the European context, the massive and manifest failure of the EU to have any political meaning, namely to be able to induce some sort of political affect of identification, is palpable. I met a former PhD student of mine from Belgrade yesterday, who now works in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Serbia and he was telling me that opposition to the EU is currently running at about 60 percent and in Croatia at about 80 percent. This is a massive shift that has occurred in the past couple of years. The failure of the Franco-Germanic fantasy of the EU has led citizens to fall back increasingly into atavistic forms of nationalism based on a politics of fear directed at immigrants, especially and most obviously those from the Muslim world. I know Finland well, and the example is extreme, but to me not that surprising. I work part of the year in the Netherlands and have watched as closely as I am able to spectacular rise of Geert Wilder's Freedom Party. Traveling around the provincial Netherlands where I work, you can feel the fear and racism that is induced by perceived ‘outsiders', who have often been there for two or three generations. We could tell a similar story about every European country I know, especially Denmark, France and Italy. I could go on.

Yet, I do not feel your Cioranian emptiness. It seems to me the discreditation and legitimation crisis of the state is good news, at least for those of us suspicious of the identification of politics with the state and the activity of government. The increasing dislocation and disintegration of governmental politics has led to something else, a massive remotivation in non-state based forms of politics. One could assemble a list of usual suspects, but you know what I'm talking about, right? Now, this remotivation of politics as a critique of the state can be reactionary, as in the case of the Tea Party Movement in the USA. But it needn't be. And this is the ground for the hope that I still have, the hope for forms of trans-state or non-state solidarity and alliance formation.

This also partially explains my delay in replying to you. I've been organising a big conference with limited resources at the New School for Social Research that finished yesterday called ‘The Anarchist Turn'. The aim of this conference is to argue for an anarchist turn in politics and in our thinking of the political. We wanted to discuss anarchism with specific reference to political philosophy in its many historical and geographical variants, but also in relation to other disciplines like politics, anthropology (where anarchism has had a long influence), economics, history, sociology and of course geography (why were so many anarchists geographers, cartographers or explorers, like Kropotkin? We need new maps). Our approach was firstly trans-disciplinary, a word I don't like, but secondly our approach also wanted to put theory and praxis into some sort of communication and that is why we had academics alongside activists, and we had many academics who are activists. By bringing together academics (like Judith Butler, Todd May, Miguel Abensour and others) and activists, activists in some case past (Ben Morea of Black Mask and the Motherfuckers) and in other cases very present (three representatives of the Invisible Committee from France), the conference tried to assess the nature and effectiveness of anarchist politics in our times.

Was the event successful? I don't know. We certainly had huge numbers of people in the room and much intelligent discussion of the history and theory of anarchism and acute discussions of tactics at the intersection of theory and praxis. But what I came away with was the feeling that the anarchist vision of federalism that one can find in Bakunin, the idea that the disintegration of the ‘normal' politics of the state has both negative and positive consequences, or perhaps better expressed, it has possibilities for action that can be cultivated and developed, and that - to go back to the original source and motivation for our conversation - perhaps something like this began in Tunisia last December with a simple and routine act of daily humiliation. The difficult issue is how to decouple such political articulations, such as the uprisings in North Africa, from the teleology of the state and logic of governmental representation, which is exhausted in my view. The goal of such political sequences is not a ‘better' form of state representation, that's for sure. The goal, in my view, should be the exit from the terrain of the state as the political territory par excellence. Empty utopianism is not the answer, I agree, but there is a ‘topianism', as Landauer would say, where new forms of political assemblage are taking shape, here and there. What should be imagined (a supreme fiction?) and promoted are local forms of politics linked together in federated, trans-local alliances. The question of politics today is the question of the formation of alliances outside the state.

I remember sitting in the back of a minibus outside Coventry and in early 1990s and Gillian Rose saying to me, ‘Keep your mind in hell and despair not'. It seems to me that we need an utterly clear-sighted, analytical diagnosis of the present that doesn't fall into a form of transcendental miserabilism, and which retains a sense of the possible, even and especially in circumstances where the impossible seems to face us and face us down.

David Morris <david.morris AT network.rca.ac.uk> is a writer and philosophy tutor based in London

Info

The Anarchist Turn was at the New School from 5-6 May 2011

http://www.newschoolphilosophy.com/arendtschurmann-symposium/

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com