Eliminating Labour: Aesthetic Economy in Harun Farocki

Reading across the expanse of Harun Farocki's oeuvre at his recent Raven Row retrospective, Benedict Seymour discovers a profound engagement with capitalism's ongoing crisis of devalorisation. How, he considers, does the eye/machine of Farocki's cinema operate on and within this process?

As if the world itself wanted to tell us something

Harun Farocki, ‘Workers Leaving the Factory' in Nachdruck/Imprint, Berlin 2001

Against What? Against Whom?, the retrospective of Harun Farocki's video installations at Raven Row in London, was an overdue opportunity to explore the German film-maker and writer's work. Intelligently curated by the gallery's director Alex Sainsbury, the show comprised of Farocki's two-or-more-screen video pieces, from the first, Schnittstelle (Interface, 1995), to his latest, Immersion (2009). It was accompanied by a season of Farocki's films at the Tate Modern and the publication of a new book of texts and essays on and by Farocki edited by Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun. In addition, Raven Row made available a good selection of his films which could be viewed on a monitor in the entrance of the gallery.

This constellation of exhibition, publication and screenings, not to mention audiences with the director and his collaborators during the course of the show, was quite a revelation. The range and continuity of Farocki's concerns across different media and over several decades became apparent in the matrix of inter-related ‘themes': the symbiotic relationship of (image) technologies across military, consumer and productive spheres, the centrality of technological and pedagogical simulation in an increasingly performance-based capitalism, a rigorous and self-scrutinising investigation of the language of cinema and television. But beyond this there was an unexpected, and timely, re-encounter with some fundamental questions concerning (image) technology that have, by and large, been overlooked or marginalised in film studies. Whether Farocki would endorse this approach to his oeuvre I'm not sure, but the essays by Alice Creischer and Andreas Sieckman, Tom Hollert and Diedrich Diedrichsen in the book, and the simultaneous availability of the gallery installations and films such as Zwischen zwei Kriegen (Between Two Wars, 1978), Wie man sieht (As You See, 1986) and Bilder der Welt und Inschrift der Krieges (Images of the World and the Inscription of War, 1988), encourage a reading of Farocki as above all an analyst and practitioner of ‘devalorisation' - perhaps the most consistent or possibly even the sole example in cinema.

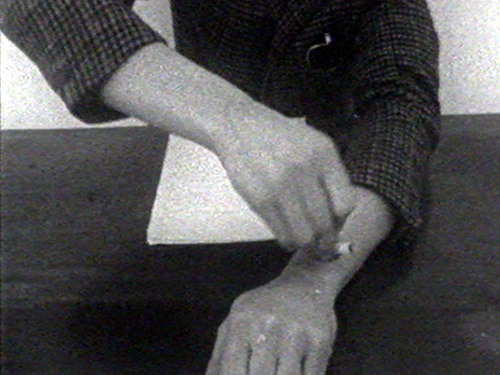

Image: still from Harun Farocki's Inextinguishable Fire, 1969

Broadly, devalorisation is the Marxian name for the loss of value from productive assets arising through the technological displacement of labour, the depreciation of existing capital by more efficient technologies, and the failure to realise products' value on the market. Devalorisation can also be used to denote the technological-social-economic process of production/destruction whereby capital deals with its contradictions at the expense of people and things. From restructuring to crisis to war, devalorisation is both the result of and response to the contradictions of advanced capitalism.

In their form and content - not to mention their cultural and institutional context - Farocki's films and writings inscribe and are caught up within such processes of devalorisation. They begin with the multiple stigmata of this process, principally, perhaps, film itself as an agent for the displacement of labour from the process of production. Faced with the tendency of technology to undermine the very basis of profit in the exploitation of human labour, capital seeks to recompose value and so avoid a self-deflating downward spiral. This happens first of all by the reconfiguration of production and the re/production of the worker, and then, when this strategy is played out, by laying waste to human and infrastructural capital. In normal parlance it is Keynesianism, but since this lays the stress on the monetary inflation and consumer economy which is necessary to the first stage of the process and tends to overlook the destructive second phase (though Keynes and his German precursor Hjalmar Schacht did not), devalorisation is a more useful and less euphemistic name. Naming and renaming, as the Farocki retrospective and its title - Against What? Against Whom? - made plain, is also an important part of devalorisation: how we divide up reality and allot agency to parts of a social process is part of the constitution and re/production of that process. Capital has often had to ‘change up' and repackage its product, and both innovation and adulteration, spin-offs and start-ups are part of the process.

The theme of devalorisation is explicit in Farocki's early films such as Nicht löschbares Feuer (Inextinguishable Fire, '69) and Between Two Wars, but persists and finds ever greater immediacy in his subsequent work. After an overt Brechtian staging of the problematic (coded vignettes, soldiers scratching the true terms of real subsumption into the soil with their bayonets), devalorisation is progressively sublimated into the very texture of video works composed, as they are, out of ‘readymade' military-industrial images of consumption/destruction. The author is, in a sense, himself steadily displaced from production. In his latest videos and installations, Farocki's sensitivity to and inscription of devalorisation is so refined that it bleeds from the interstices of the shots; rather than directly announcing his subject as narrative or theme it is there in the very instrumental (Farocki dubs them ‘operational', as opposed to expressive) images of which his films are constituted.

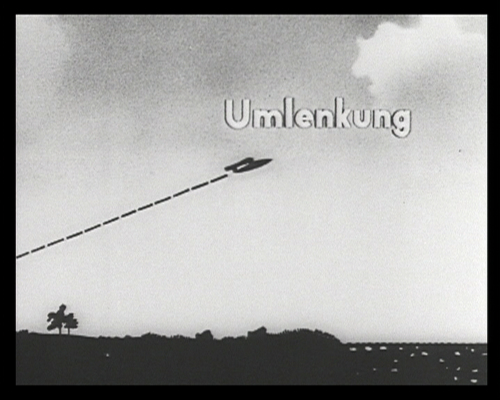

In works such as Auge/Machine III (Eye/Machine III, 2003) a two-screen work in the Raven Row show, the progressive recomposition of value is evidenced by the cut from the aesthetically embellished, animated cartoon of a second world war flying bomb made for the instruction of German pilots to the zero-degree aesthetics-by-accident of a Cyclopean cruise missile's ‘suicide camera'. Progressive abstraction and instrumentalisation of the image, from aerial photography to CCTV and modern missile targeting software, means that the ‘inscription of war' is already the inscription of devalorisation.

Image: still from Harun Farocki's Eye/Machine III, 2003

The film-maker responds in a kind of Brechtian self-amputation, rather than re-enacting these processes as narrative or searching for an image to represent them, he lets the images interrogate themselves. No need for CCTV camera players: the draining of narrative or mise-en-scene is already the truest index of the deepening alienation of the world. Here human labour has been reduced to the occasional monitoring of machine images (the ‘Eye/Machine'), a step sideways from production (and indeed, destruction) which Marx foresaw in the Grundrisse, but whose enormity and perversity long since outstripped 19th century anticipations, not to say 1960s dreams of a ‘leisure society'. The film-maker mimics this elimination of the human, of labour, becoming a kind of latter-day Flaubertian artist-deity (or artist-engineer), absent from his own works, from the field of battle, but for occasional high precision textual or verbal fusillades. Unlike Benjamin's programme of converting authors into producers, however, this is authorship in an age of advanced non-reproduction. Farocki's authorial ascesis corresponds to a development of forces of production which are increasingly non-reproductive - innovations which eliminate the worker from the processes of (advanced) production while undermining the overall process of reproduction of the collective worker. Farocki's formal economies coincide with innovations in imprisonment, security, finance and systems of control. The latter contribute to the policing of the post-industrial reserve army or support the reproduction of a growing (but vast) minority of non-productive servants of capital. As such they are ‘non-productive forces', or overtly destructive as in the case of the missile tracking systems in Eye/Machine III. Farocki's films map the growing indistinction of technologies of reproduction and destruction, the concomitant suppression of productive forces apparent within even the most advanced technologies.

Farocki's large corpus of writings, particularly his essays in the now defunct Filmkritik, exist in a complementary relation to his films' apparently growing verbal reticence. Found images converse together, punctuated by measured, not to say minimal interventions that subtly underscore, nudge or counterpoint the patient, self-effacing work of montage. The author survives the demise of production as a shimmer of irony haunts every shot, reinflecting otherwise bald images of command/control with a kind of ‘grin without a cat' critique. If nothing else, Farocki manages the sarcastic refunctioning of neoliberal teaching films, ‘capitalist Lehrstück' as Kodwo Eshun and Antje Ehmann term them. A vast collective mis-education is turned against itself in films such as Leben - BRD (How to Live in the German Federal Republic, 1990), the tragedy of corporate pedagogy turned into a grotesque but often highly amusing farce.

Farocki's economy finds a solution to the old Adornian-Brechtian enigma of how to represent society without reducing its complexity and softening its horror by simply applying direct cinema techniques to capitalist Lehrstück. In the process both direct cinema and Brecht are dialectically transformed. Filming and montaging the theatre which capitalism itself is perpetually staging and restaging in an era of accelerated restructuring and destruction turns it into satire, wordless auto-critique.

If devalorisation is Farocki's great theme, its primary cause, the elimination of living labour, seems to me to be the key leitmotif of his films. From the imposition of abstract labour in the phase of formal domination to the present ‘surreal subsumption', capital progressively evacuates and, tendentially, displaces work from re/production.1 This theme is repeated across different cinematic registers and modes, from the symbolic and graphic figure of the worker's absent (dead) body outlined in chalk on the ground at the end of Between Two Wars (the post-WW1 revolutionary ‘Gesammtarbeiter' first displaced from production, then murdered by capital) to the lone worker silently superintendening the automated pre-fabrication of a brick wall in contemporary Germany in Vergleich über ein Drittes (Comparison By a Third, 2007). Farocki presents this process of (technological) displacement dialectically, and globally, however - hence there is none of Negri or Baudrillard's one-sided totalisation or euphoria here, no simple ‘end' or ‘dematerialisation' of work. Instead what disappears at one pole of production is discovered remerging at another, running in strict (combined and uneven) parallel. Comparison is a hypnotic two-screen work contrasting the almost completely automated production of a brick wall in a cutting edge European factory with the very social and highly labour intensive process of wall building in Africa. True to Farocki's notion of ‘soft montage' discussed in the essay of the same name reprinted in Against What?, one image is questioned and interpreted by another, held in a dialectical tension which forbids either nostalgia or unmediated technicist enthusiasm. Neither the celebration of ‘appropriate technology' and ‘community' nor the worship of high tech and efficiency that is its counterpart in the global constellation of devalorisation prevail. The two poles posit and presuppose, and here also interrogate and criticise, each other. The complete absence of commentary in this work is exemplary - the viewer is left to do the intellectual labour of reading and mediating the contrasting images.

Since the '80s, Farocki has increasingly worked under a self-imposed taboo against the staging of material, instead relying respectively on a very particular form of direct cinema and found footage:

No actors, no images made by myself, better to quote something already existing and create a new documentary quality. Avoid interviews with documentary subjects; leave all the awkwardness to the idiots you distance yourself from.2

Farocki's unalienated labour, vanishingly thin as it becomes, is continually played off against the alienated labour his films scrutinise and seek to understand. One might question to what extent - here and in other aspects of leftist politics and culture - this ascesis is a dialectical challenge to capital or merely its double. Does minimalism shade into a moralised militantism, formal economy as ‘negation of the negation' acting to produce a parallel politico-aesthetic devalorisation? Or, insofar as minimalism can helplessly undergo transubstantiation into the stuff of luxury (Raven Row is no third world building site), is an aesthetic of poverty - like other leftist cinematic propositions such as an ‘aesthetics of imperfection' - not doomed to become its niche marketed opposite?

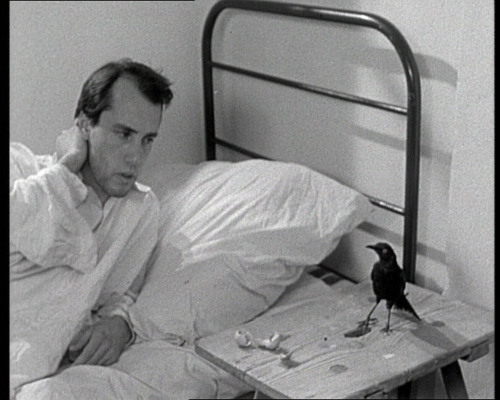

Image: still from Harun Farocki's Between Two Wars, 1978

Farocki is ahead of such criticisms insofar as he explicitly thematises the contradictions of his work's own productive forces. His withdrawal from narrative cinema is at the same time, in parallel with capital's penetration of the personal, affective and communicational worlds of the (former) worker, the exploration of a vast new world of (un/productive) images. Farocki pioneers new fields and forms of image analysis by scouting the emergent scenes of capitalist devalorisation - supermax prisons, combat simulators, maternity class and police training exercise, or venture capitalist negotiation session. Capital's growing interest in training and rehearsing, simulating and re/modelling every inch of the ‘social factory' appears in Farocki's work as a project not of simple ‘expansion', but rather, I would argue, of involution and contracted social reproduction. Increasing precision is applied to increasingly unproductive and outright destructive functions. For example, Ich glaubte Gefangene zu sehen [I Thought I was Seeing Convicts, 2000] presents us with images of the Corcoran supermax prison in California as a site where guards effectively rehearse and stage gladiatorial combats between the inmates, then shoot them down. The prison becomes a kind of (CC)TV studio churning out state snuff movies. Capital combines ceaseless re-education with the progressive scuttling of material existence.

The Raven Row archive of Farocki's works revealed a film-maker confronting capital's tendency, beyond a certain point in its development, to wipe out not only over-valued exchange values (as in our current economic crisis) but, increasingly, the very forces of production - machines and humans, mental and environmental resources. Already in Inextinguishable Fire (1969), Farocki had examined the emblematic scandal of Dow Chemical, a company whose own technical efficiencies oblige it to turn its surplus (domestic, productive) output into materials for destruction and war - i.e. unsellable petroleum becomes napalm, shipped out to Vietnam where it is used to flay the bodies and environment of the ‘communist' antagonist. Rather than propaedeutically expose his audience to images of napalm's horrific effects, Farocki uses a kind of institutional tracking shot to make visible in one movement the inseparability of the productive and destructive arms of a single company. Famously, Farocki, in the guise of a TV announcer, begins this movement by stubbing a cigarette out on his own forearm while the voice-over explains that napalm burns at 3,000 degrees Celcius, a cigarette at just 400. This gesture has captured most of the discussion, but it is the succeeding sequence, based around a mock up of Dow Chemical's internal division of labour, that makes good the initial gestus. The film is a study in the right hand's carefully constructed ignorance of what the left hand is doing, of a (self-)alienation which is not simply epistemological or ethical but institutional and systemic. Hence Farocki's self-wounding gesture is not an actionist coup de théâtre but rather a characteristically economical and accurate physical synopsis of the self-destructive (and necessary) separation that the system is predicated on.

The ensuing analysis reveals that Dow is no isolated malefactor but rather simply one exemplary node in a vaster system of production/destruction. It is identified as a potential site of struggle and refusal - were the scientists employed there to start thinking their activity in its totality and practically refusing it in concert with other workers at different points in the division of labour. Overt exhortations of this kind are notably absent from the director's later work, but the focus on the ambivalence of capitalist ‘rationalisation' remains a constant.

Image: still from Harun Farocki's Between Two Wars, 1978

In Farocki's films capital is a system of production, but above all of production through and at the cost of intensifying destruction. In Between Two Wars (1978) Farocki draws on Alfred Sohn-Rethel's Marxist analysis of the economy and class structure of fascism to posit an analogue between post-WW1 Germany and consumer capitalism after '68. The key image of capital's self-destructive ‘recycling' in Between Two Wars is presented in a scene in which one worker tells another his dream, of a bird that hatches then eats its own egg. The second worker replies with the story of the scientist Kekulé. One night while he was working on the problem of the molecular structure of benzene Kekulé dreamt of a serpent eating its own tail. This archetypal image of regeneration gave him the key to the circular structure of benzene. Spiritual figure became topology, a real and practical model for material production. The worker similarly finds in the image of the bird eating its own egg a formula for immanently overcoming capital's problems. He imagines reorganising production such that the waste products of one industrial process are put to work to help power another: ‘a network of pipelines' could use exhaust gases from coking to heat blast furnaces for smelting. As the film goes on to show, however, this first ‘constructive' phase of devalorisation stores up a second, destructive one. As Sohn-Rethel showed in his analysis of the German steel industry of the '20s, this very ‘rationalisation' resulted in an increasing contradiction between production and consumption as capitalists were unable to realise the value incorporated in products on the market. This leads capital to a new ‘solution': the non-reproduction of workers and the production of non-reproductive commodities - chiefly weapons. Having first broken the resistance of the working class with the help of the unions and socialist parties, militarisation of the economy and, ultimately, war proved necessary to bring the market and the productive forces back into alignment. Nazism is presented by Farocki as the only political form capable of securing continued capitalist accumulation, a process of social self-cannibalisation. Farocki's film refuses the comforting notion of a possible return to some social democratic ‘alternative' - instead it suggests the proximity of the workers' movement and fascism, of the left and right wings of a (productivist, and nationalist) socialism. Like the different branches of Dow Chemical, socialism's productive and destructive arms are inseparable, mutually constituting. The recognition may hurt, like a self-administered cigarette burn, but if one wants to stop reproducing the tragedy of capitalist ‘development' one must try and grasp it.

Farocki's later work explores how, from the birth of cinema and the rise of socialism down to the present crisis, the affirmation and elimination of labour is as integral to cinema as it is to other machines. In the Raven Row show, the installation Zur Bauweise des Films bei Griffith (On Construction of Griffith's Films, 2006) explored the logic of Taylorism operating in cinematic form. The introduction of the shot/reverse shot, we are told, gives us two sets for the price of one and enormously increases the transferential ‘productivity' of film grammar in the process.3

The dialectics of (abstract, industrial) labour in cinema are pursued again in Workers Leaving the Factory. A row of 12 monitors showing excerpts from 11 decades of feature, documentary and promotional films, Workers does what it says on the can and shows workers leaving factories. It is not only a document of the evolution of film and of factories but, as Bert Rebhandl puts it in Against What?, it posits the continual ‘reappearance' of the Lumière's first film - the primal scene of workers exiting the inventors' photographic factory in Lyon (Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon, 1895). Without commentary, the installation implies that the cinematic apparatus is founded on a constitutive disavowal of production, both the world of industrial work from which the cinema classically posed an escape, and its own fantasmatic production line - the Taylorist, 24 frames-per-second machine behind and within the projected image.

What Hollywood screened out - the factory - and socialism deified - the worker - it simultaneously destroyed. Devalorisation made visible what it sought to eradicate, simultaneously consigning much of the labour force to the status of invisible non-people. The elimination of the worker coincides, in the phase of Fordist devalorisation, with a cult of the worker as identity and a cull of those identified as non-workers. If the process begins with the birth of cinema - with the image of workers leaving the factory - in the present moment of crisis this displacement has come full circle: the (social) factory is closing down all over the shop, everywhere we look the doors are being forcibly levered open and the worker expelled - by capital. Rather than running for the exit, workers may think of occupation, or indeed of new forms of solidarity capable of turning this new ejection to their own advantage, a step - or leap - toward their self-abolition as capital.

Increasingly, as Farocki's films suggest, one is dealing with a combination of ‘surplus humanity' and ‘guard labour' - the warehousing, surveillance and/or destruction of one fraction of the class by another. Farocki's images of a world inscribed and disfigured by value in crisis remain pertinent as we enter an era in which the assertion and abolition of the working class must arguably converge if the workers of the world are not to undergo another, drastically intensified, phase of devalorisation.

Benedict Seymour <ben AT kein.org> is a contributing editor to Mute and is currently working on a film treatment about a popstar who survives a serious car crash to discovers that he can suddenly see the price of everything he looks at

A full length version of this article is available online at

http://www.metamute.org/en/content/eliminating_labour_aesthetic_economy_in_harun_farocki

Info

Against What? Against Whom? was at Raven Row, London, 19 November 2009 - 7 February 2010. This project was linked to ‘Harun Farocki. 22 Films 1968 - 2009', a season of single-screen films and events at Tate Modern, 13 November-6 December, curated by Stuart Comer, Antje Ehmann and the Otolith Group.

Kodwo Eshun and Antje Ehmann, (eds.), Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom?, commissioned by Raven Row, published by Koenig Books, 2010.

Footnotes

1 See my ‘Drowning by Numbers - The Non-Reproduction of New Orleans', in Proud to be Flesh, A Mute Magazine Anthology of Cultural Politics After the Net: ‘After devalorisation, that is the destruction or ‘‘non-reproduction of labour power'' through (Fordist) recomposition, today we have the final stages of devalorisation through its Post-Fordist decomposition. After the ‘‘real subsumption'' of the worker under capital, we have surreal subsumption: the return of absolute surplus value extraction in formerly relative surplus value centred economies. [...] capital now attempts the destruction of already reduced standards of living and expectations on the part of already ravaged communities of workers.'

2 Harun Farocki in a note to Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun, August 2008, quoted in Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, Koenig Books, 2010.

3 ‘With the introduction of shot-countershot, the room was divided into two, making two sets out of one, just as the introduction of industrial production introduced the evening shift' - Harun Farocki, ‘Shot/Countershot: The Most Important Expression in Cinematic Law of Value', quoted in ‘A to Z of HF or: 26 Introductions to HF' by Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun in Against What? Against Whom?, ibid..

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com