On Dog Shit and Open Source Urbanism

Here a presentation i did recently on citybranding.It is a work in progress. A bit of a rough sketch.Hope it will be of interest to someone.

Presentation DEAF Sa 14-04: Marked Up City, V2 Rotterdam On Dog Shit and Open Source Urbanism Merijn Oudenampsen

1)

Like the classic work of literature that defines a new current, the iconic branding project that set the standard, the classic from which all other cities derive their inspiration, is I Love New York. Launched in 1977 and promoted with the help of famous celebrities such as John Lennon, the branding campaign with the now famous logo of graphic designer Milton Glaser immediately became a hit. It was initially devised to attract tourists, but it emitted a strong message to New York’s population as well: love it or leave it.

Especially the circumstances surrounding the birth of the branding campaign are worth mentioning here. I will take my cue from geographer David Harvey, who has written extensively on this topic. At the beginning of the 70s, New York was in a fiscal crisis. Rapid deindustrialization and suburbanization had left the city impoverished. Strikes, racial divisions, rampant crime and continued political confrontation of marginalized populations marked an ever deepening urban crisis. In a gesture that reminds of the so-called closure of the war in Iraq, president Nixon at a certain point simply declared the urban crisis to be over, and subsequently squeezed federal funding. The government of New York started accumulating huge debts over the next years, until the city’s banking elite wouldn’t take it anymore and decided to apply austerity measures and seize control over the city’s budget. An effective coup d’etat of what was until then a notoriously left wing city. Compared by David Harvey with the takeover in Chile, New York thus became on of the prime inspirations for the politics of the Reagan years and the Washington consensus that would later be famously exported by IMF and the WB. I quote: “The term of any bail out should be so punitive, the overall experience so painful, that no city, no political subdivision would ever be tempted to go down the same road.” This is the secretary of treasury, William Simon.

The public infrastructure constructed by the left wing municipality and its powerful unions deteriorated markedly. Thousands of public sector workers were fired and social services all but seized to exist, restricted geographically to the economic and touristic core of the big apple: Manhattan (while the rest of the apple was left rotting). The financial sector decided to mobilize the cultural sector to sell the image of New York as a tourist destination specialized in cultural consumption. Thus ‘Delirious New York’ erased the collective memory of democratic New York. This was the backdrop of the invention of the I love New York campaign, accompanied by an aversion to dog shit:

“Well, it was the mid-seventies, a terrible moment in the city. Morale was at the bottom of the pit. I always say you can tell by the amount of dog shit in the street. There was so much dog shit because people didn’t feel that they deserved anything else, right? I mean you were just walking through all this dog shit day after day, in this filthy city, garbage, and so on. And then the most extraordinary thing happened: There was a shift in sensibility. One day people said, “I’m tired of stepping in dog shit. Get this fucking stuff out of my way.” And the city began to react. They said, “If you allow your dog to crap on the street, you have to pay a fine of $100,” and within a very short time it became socially untenable to allow your dog to shit on the street. Now, I don’t know what produces those behavioral shifts, right? From one day where it’s OK, and then suddenly the city simultaneously got fed up and said, “It’s our city, we’re going to take it back, we’re not going to allow this stuff to happen.”

(Graphic Designer Milton Glaser in literary magazine The Believer, September 2006)

The question of “what produces these kind of behavioral shifts”, is quite central to this presentation, as I will argue that citybranding is all about reprogramming behavior of city dwellers.

2)

Amsterdam would prove to be a somewhat less cruel parallel to developments in New York.

The city's socio-economic trajectory was pretty similar – Amsterdamned: closure of the Ford factory and the shipping docks, a city marred by unemployment and the influx of drugs, civil unrest in its streets embodied by a huge squatting movement - and the branding campaigns were mirrored in their distaste of dog shit. Earlier attempts to label Amsterdam Reuzenstad and Amsterdam Modestad had backfired. In 1975, a giant puppet was placed on Dam square to celebrate Amsterdam Reuzenstad (Amsterdam Giant City). Soon a small dwarf was placed beside it by dissenting groups of neighborhood associations and squatters. Not much later the giant was put on fire and never returned to the city again.

In Amsterdam it was the appointment in 1983 of social-democrat leader Van Thijn that initiated the shift to market-led city politics. A branding campaign was started with the slogan “Amsterdam Heeft ‘t”, with a smiling Canal house for an A.

A round circle, a new cabal was formed between politicians and the city’s business elite, that gathered in the residence of the mayor to privately discuss the future of the city. A new economic development discourse led to a cleansing mechanism in different layers of the city’s organizational structure. Those that could work with the new priorities displaced the old style public officials: restoring private initiative, the development of large scale office and tourist infrastructure and the advancement of mobility through construction of a 4-lane inner city highway.

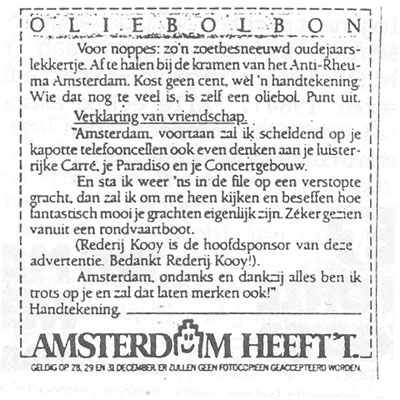

Advertisement in Dutch mayor papers at the launch of the 'Amsterdam Heeft 't' branding campaign, October 1984.

Advertisement in Dutch mayor papers at the launch of the 'Amsterdam Heeft 't' branding campaign, October 1984.

Amsterdam Heeft ‘t, in all its cute beauty, was a seed that contained all the characteristics of the present Citybranding practice. Firstly, government makes way for governance by a coalition of public and private actors, resulting in not-so-public decision making processes. Secondly the branding campaign had a dual purpose: The official objective is naturally the attraction of tourism and inward investment, but it serves just as important a purpose in reprogramming the behavior of its citizens, and neutralizing dissenting visions.

This was done by applying management techniques aimed at increasing output through promoting loyalty and identification of the workforce. A poster campaign was started stating: “genoeg geklaagd, genoeg gekankerd, genoeg gejammerd, genoeg gezanikt”. (these are all Dutch words for complaining, just like Eskimos have a hundred words for snow, we have lots for complaining) The As in the word were filled in by an unhappy canal facade, then the Amsterdam Heeft ’t slogan was printed below with a smiling canal house, the text stated: “That chagrin face has to be changed. The façade (of the canal house) is already smiling. Now it’s your turn.” Reference was also made to the famous song line of Danny de Munk, “Amsterdam is poep op de stoep en haat op de straat”, saying that even Danny couldn’t do without his favorite shit city. Blank space was left in the middle, as an interesting participation mechanism, people were even officially encouraged to add their own message.

Similar experimental advertising techniques were used elsewhere. A small oliebol advertisement started to appear in newspapers around new year. You could pick up an oliebol for free if you signed a statement of pride in Amsterdam, non-participants were deemed an oliebol themselves.

Receipt for a free oliebol, on condition of signing a declaration of pride for Amsterdam

Receipt for a free oliebol, on condition of signing a declaration of pride for Amsterdam

The campaign was joined by a strong media presence of mayor van Thijn who stated: “No cockiness please, with your housing problems, your traffic chaos, your drugs and small crime.” “Every Amsterdammer has to become a seller of this town”. Non-participants and critics of the campaign were put aside as not real Amsterdammers, zeikerds, or just simply oliebollen.

This was maybe shown the clearest with the city’s cleaning trucks, which all carried Amsterdam Heeft ’t slogans, “all real Amsterdammers roll up their sleeves”, “if you don’t participate you’re an asocial”.

Thus citybranding becomes the expression of a realignment of urban politics from rights based welfare (being cocky) to performance based workfare (rolling up sleeves, being a seller). Invoking a football club like loyalty principle, its subliminal message (or maybe pretty public secret) is that Amsterdam is a company whose primary interest is to sell a product, not to provide services to its citizenry. Don’t ask what your city can do for you, but what you can do for your city. The I Amsterdam campaign is definitively more slick and elaborated, and the disciplining mechanism is now called “globalisation” or “interurban competition”, but in the end it contains much of the same techniques.

“The people of Amsterdam are Amsterdam. The diversity of Amsterdam’s business community, the differing backgrounds of its residents and the wide and innovative perspectives of its citizens are the lifeblood of our city. Therefore we, the people of Amsterdam, wish to speak for the city of Amsterdam. Amsterdam is our city, and it’s time for us proudly to voice our dedication and devotion to Amsterdam.” (Extract I Amsterdam manifesto, IAmsterdam.com)

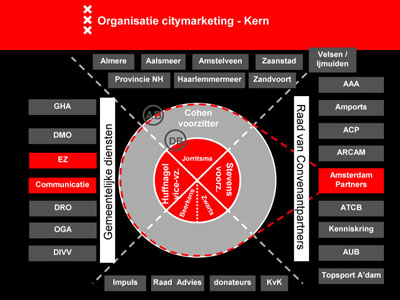

Visualisation of I Amsterdam citybranding governance structure

Visualisation of I Amsterdam citybranding governance structure

The I Amsterdam campaign sells Amsterdam to interested clients, with the usual range of T-shirts, coffee mugs, key rings, umbrella’s and assorted paraphernalia. Billboards in bus stops show smooth photographic representations of Amsterdam and Amsterdammers superimposed with an I Amsterdam logo, to make clear to those on city streets that also their identity and presence in the cityscape is part of the brand Amsterdam. To exclude those parts of the city image that are not supposed to be enhanced, the branding campaigners can exert monopoly control through copyright laws. New York has filed over 4000 law suits concerning the IloveNY logo. Recently the Amsterdam branding crew has started to step down on sex postcards and weed being sold with an I Amsterdam slogan.

To properly understand the ongoing popularity of citybranding practices, we have to place it in a larger context. It is part and parcel of a bigger shift hitting the city, causing the Keynesian management of bygone eras to be replaced by an entrepreneurial approach. The rise in importance of ‘footloose’ productive sectors for cities’ economic well being has led to increased interurban competition. Amsterdam is pitted against urban centres such as Barcelona, London, Paris and Frankfurt, in a struggle to attract economic success in the form of investments, a talented workforce and busloads of tourists flocking to the city. The ever present threat of inter-urban competition is continuously being rhetorically invoked and inflated, replacing previously dominant considerations of the public good. To illustrate my point, recently even the discussion on whether to discontinue a prohibition of gas heaters on the terraces of Amsterdam cafés were framed in these terms: ‘It’s a serious disadvantage in comparison with cities like Berlin and Paris’, according to the leader of the local social democrat party. The opinion of the city’s population itself wasn’t even mentioned in the newspaper article.

The dominance of entrepreneurial approaches to city politics is the feature of a new urban regime, labeled by scholars as the ‘Entrepreneurial City'. With its origins in the US reality of neo-liberal state withdrawal from urban plight, it has taken some time to arrive in the corporatist Netherlands and filter through the minds of its policy makers. In this new urban regime, independent from the color of the party in power, the public sector displays behavior that was once characteristic for the private sector: risk taking, innovation, marketing and profit motivated thinking. Public money is invested into private economic development through Public Private Partnerships, to outflank the urban competition. Hence the rise of urban mega developments and marketing projects such as the Docklands in London, the Guggenheim in Bilbao or the Zuidas in Amsterdam. A concern voiced by critics is that although costs are public, profit will be allocated to the urban elite, hypothetically to ‘trickle down’ to the rest of the population.

To face up to this new market reality, where cities are seen as products, and the city council as a business unit, Amsterdam inc. has launched the branding projects I Amsterdam and Amsterdam Creative City. One of the first steps of the new progressive city council, once installed in the spring of 2006, was to launch a ‘Top City Programme’, aimed at consolidating the city’s ‘flagging’ position in the top ten of preferred urban business climates:

"Viewed from an outsider’s vantage point, Amsterdam is clearly ready to reposition itself. This is why we’ve launched the Amsterdam Top City program. In order to keep ahead of the global competition, Amsterdam needs to renew itself. In other words, in order to enjoy a great future worthy of its great past, what Amsterdam needs now is great thinking."

Marketing tool: visualisation of desired brand identity I Amsterdam

Marketing tool: visualisation of desired brand identity I Amsterdam

Although modest in their budget the I Amsterdam and Creative City marketing campaigns are conceptually advanced (and extensively present in the public’s consciousness), for city marketing is the apex of consumer generated content, the dominant trend in marketing techniques. A central rol in the immaterial offensive is reserved for the city’s cultural sector. Instrumentalizing its cultural production towards the attraction of tourism and the ascendance of real estate value. Cultural production is increasingly becoming scripted, or prescribed into the generation of traffic. Visitor numbers, not the contents, are the new assessment of quality. Thus the Rembrandt year being a cultural high. The city’s cultural funding is increasingly geared to cross-over projects between the arts and the economy. Of course the great threat of competition is again invoked: “Despite big investments of the council and the national government, the cultural significance of Amsterdam, and accordingly the international position of Dutch culture, is under pressure”.

Creative hipsters, the modern day dandies, serve as a communicative vessel for branding projects; in between concept stores, galleries, fashion- and street art magazines, a branded cultural economy expands itself over the urban domain and in the public realm.

3) Hardware / Software

Interestingly enough, real estate entrepreneurs in Amsterdam have begun to describe urban development programs with the analogy of urban hardware (the city’s infrastructure) and software (its programming). A big part of the value of new developments is of course dependent on its image, just like any product. What real estate developers have found out, is that prescribing the use and identity of “hardware” by cultural “software”, adds value. Cultural institutions and temporary art projects are attracted to generate traffic, bring real estate “up to flavor” and spice up prices. Most large developments now have cultural institutions, the Zuidas has a design museum, the southern docklands the Muziekgebouw and the northern Docklands the Filmmuseum. Branding has been labeled as the dominant trend in the restructuring of social housing as well, resulting in a large amount of schemes to temporarily house artists in neighborhoods to be upgraded. Recently, the alderman of culture even proposed to install a real estate tax, to skim away culture’s immaterial value. Whereas the immaterial brand value of companies like Coca-Cola, McDonalds or Nike exceeding 60% of total market capitalization - in cities, surplus value generated by its software is redirected back into its hardware.

The distinction between urban ‘software’ and ‘hardware’ was initially coined as an architectural term by the pop-art architecture group Archigram, to champion the use of soft and flexible materials like the inflatable bubble instead of modernist ‘hardware’ realised with steel and cement. Together with contemporaries such as the Italian group Archizoom and publications such as Raban’s Soft City, Archigram leveled a critique against deadpan modernism, putting forward a more organic conception of the city as a living organism. Urban software thus acquired its present day computer analogy, where software is the ‘programming’ of the city and hardware its ‘infrastructure’. Much like the SI - experimenting with the bottom up software approach through psychogeography and the dérive – subjective, organic and bottom-up approaches became a focus point for utopian urbanism.

The figure that inspired much of those tendencies was the flaneur as imagined by Baudelaire and Benjamin. The stroller of city streets, botanist of the sidewalk, the shopper that didn’t shop but just observed was according to them exemplary to the modern urban experience. But whereas the flaneur was fascinated by the commodities in the passages, the first Parisian luxury shopping centers, right now the entire city can be experienced as a commodity.

The tourist industry in particular is an extreme practice of commodity fetish, selling cliché and ossified images, a hyper reality of Amsterdam, consisting of canals, clogs, tulips, windmills, Rembrandt, cheese, weed and sex. The flaneur has been programmed to become the present day tourist, following their obligatory rounds of highlights and Lonely Planet must-sees. What I mean by commodity fetish is that the tourist has no relation to the city’s population but one mediated by consumption, it doesn’t construct anything, it only consumes imagery.

The neoliberal city is a city whose software has become increasingly scripted, through codes of conduct, local ordinances, and an intensified police presence. The sanitizing of city streets from unwanted uses and imagery has led to the exclusion of marginal populations. Not so long ago, homeless people staged a protest meeting wearing T shirts with the slogan “I Amsterdam too”. Entrepreneurial city politics thus function as an inclusion and exclusion mechanism: while the city looks outside for tourists, a talented workforce and investments, parts of the local population that are not considered economically productive are increasingly seen as an obstacle to development. This surplus population is increasingly displaced towards the periphery.

Branding schemes thus become an attempt to build competitive ‘urban software packages’; or to ‘program’ space, an expression of French urbanist Lefebvre to denote the top-down organisation of space. From the functionalist planning for the population, we have to gone to functionalist planning of the population. To continue with the computer analogy, the first problem with these top-down approaches is that their ‘source code’ is undisclosed. When the city’s kernel is increasingly geared to interurban competition, policy no longer needs legitimizing. We have entered the era of so called post-political politics, no content, but form.

In the ’60s Lefebvre argued for a right to the city, which came to inspire much of the urban struggles of that era. ‘the right of the city signifies the right of citizens and city dwellers, (...), to appear on all the networks and circuits of communication, information and exchange.’ In the present, what this calls for is open source urbanism.

References:

Bekius, Sjoerd, Jaap Draaisma en Nienke Mier (1985) Amsterdam City, wat verbeeld je me nou? : Over ideologiese processen in de binnenstad van Amsterdam. Doktoraal skriptie Planologies en Demografies Instituut, Universiteit van Amsterdam. Amsterdam: UvA.

Gemeente Amsterdam (2006) Amsterdam Topstad: Metropool. Economische Zaken Amsterdam, Amsterdam.

Hajer, Maarten (1989) Discours-coalities in politiek en beleid: De interpretatie van bestuurlijke heroriënteringen in de Amsterdamse gemeentepolitiek. In: Beleidswetenschap 1989(3), pp242-263.

Harvey, David (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kidd, Chip (2003) Chip Kidd talks with Milton Glaser. The Believer Magazine, September 2003.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nichelson Smith, Oxford, Blackwell, 1991.

Raban, Jonathan. Soft City, London: Hamilton, 1974.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com