Digital Salvation

For a while now, old, long outdated video game consoles of the 80s such as the Atari 2600 or the Vectrex have been enjoying something of a renaissance. They've found their way into the canon of good taste; a multitude of records and T-shirts are testimony to that. PC emulators for old school games are being introduced everywhere with verve, as if every reviewer has to prove his or her proper socialisation with the holy trinity of Pong, Space Invaders and Donkey Kong. But the nostalgic and sentimental enthusiasm for the cute little games of yore is being played out on another level as well. Strategies are also being developed for saving the endangered artefacts of digital culture.

For a while now, old, long outdated video game consoles of the 80s such as the Atari 2600 or the Vectrex have been enjoying something of a renaissance. They've found their way into the canon of good taste; a multitude of records and T-shirts are testimony to that. PC emulators for old school games are being introduced everywhere with verve, as if every reviewer has to prove his or her proper socialisation with the holy trinity of Pong, Space Invaders and Donkey Kong. But the nostalgic and sentimental enthusiasm for the cute little games of yore is being played out on another level as well. Strategies are also being developed for saving the endangered artefacts of digital culture.

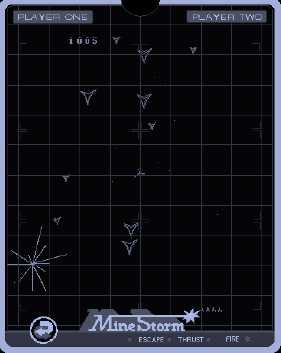

A particularly charming console, Milton Bradley's (MB) Vectrex, has become the darling of retro gamers. Vectrex was the system every kid wished for but never got because it was too expensive. It appeared on the market in 1982, a single console with a built-in monitor. The main attraction of this mini-arcade was that the screen featured not pixels (as a television does), but vectors. Razor sharp lines, unfettered by raster points, can be scaled at lightening speed, and this is what jettisoned Vectrex into the pantheon of arcades games, right up there with Tempest, Space Wars and Asteroids.

To keep costs down, MB decided on a black and white screen, but nevertheless wanted to bring a little colour into the game as well. So every game came with coloured filters one could stick in front of the screen, giving the game a unique aesthetic. In short, Vectrex was abstract modernist funk.  A quarter of a century later, Vectrex is still around and is, in fact, more alive than ever. Tom Sloper, who programmed the killer games Spike and Bedlam for the Vectrex and has since designed around eighty games on just about every imaginable platform for Activision, beams, "My old Vectrex-era cohorts and I are astounded that there is now a thriving community of Vectrex fans, that there are people creating new Vectrex software and cartridges."

A quarter of a century later, Vectrex is still around and is, in fact, more alive than ever. Tom Sloper, who programmed the killer games Spike and Bedlam for the Vectrex and has since designed around eighty games on just about every imaginable platform for Activision, beams, "My old Vectrex-era cohorts and I are astounded that there is now a thriving community of Vectrex fans, that there are people creating new Vectrex software and cartridges."

No small feat. The computer and entertainment industries thrive on amnesia, full speed ahead to the future, with no looking back. Every sixteen months, the power of processors doubles, and the storage capacity for digital media is all but unlimited. One would think that these would be terrific times for the preservation of the output of our civilisation.

Hardly. The rancid cartridges and obscure consoles crammed together at flea markets could serve as a metaphor for a looming informational disaster. In the shift from atoms to bits, any digitally stored information for which we no longer have instruments with which to read it will become indecipherable.

But for how long can these rows of zeros and ones actually be stored? At the beginning of the year, an industry-sponsored study by the National Media Institute in St. Paul was released which examined the life expectancies of digital media. The study put an end to the myth of eternal storage. At room temperatures, magnetic tapes can be expected to last for just twenty years, while CD-Roms vary in their durability between ten and fifty years.

But even if magnetic tapes are still intact, the instruments necessary for them to be of any use have often already been tossed onto the silicon heap of history. "Imagine an encyclopaedia program that only runs on Windows 2.0," says Tom Sloper, describing a typical situation. "Somebody would have to have a machine with Windows 2.0, with an appropriate CPU and the appropriate audio and video cards and drivers, in order to run the software."

Strategies for salvaging obsolete hardware and software are beginning to evolve. The most refurbished of models will turn up after all in the video game community, whose members might merely be trying to revive their childhood memories, but who are also at the same time developing a blueprint for dealing with obsolescence in general. It's these people who lovingly scan in old manuals or upload onto the Net the source code of games or the smallest detail of the cartridge design of their favourite platform. They're creating an infrastructure which makes it possible for, say, the 21-year-old Londoner, Andrew Coleman, to program a new Vectrex game called "Spike goes Skiing" (Spike was the Mario of the Vectrex universe). "I think it's great what people are doing to try and help preserve the whole 'culture'," says Coleman. "The archives that are out there on the Internet hold just about every game written for every classic system, including arcade machines."

And what about hardware? If the Vectrex hasn't gone the way of the E.T. poster on the wall in the romper room, the machine is worth a very tidy sum indeed. "Let's face it, the average life expectancy of a microchip is about 50 years. After that enough of the silicon will have oxidised to render it unusable," says Coleman, and goes on to predict that, "In 40 years time there will probably be only a handful of working Vectrex machines and games in the whole world. I think that the emulation scene is the only hope really for keeping these games playable. At the moment, there are emulators for the PC which will let you play just about any old game on a standard computer. The emulators and game files can easily be backed up and transferred onto new media over the years so there's no reason that these games should be lost." Coleman concludes, "There are literally thousands of games out there that took a great deal of work to produce in the first place. I don't want to see all that work lost."

US computer scientist Jeff Rothenberg of the RAND think tank has been addressing the problem of loss of digital data to obsolescence. As early as 1992, he proposed the use of emulation "as a way of retaining the original meaning, behaviour, and feel of obsolete digital documents." And sees his efforts validated in the DIY video game emulators. "I see the use of emulation in the video game community as a 'natural experiment' that suggests - though it doesn't prove - the viability of this approach. Nevertheless, the success of the video game community provides significant evidence for the ultimate viability of the emulation approach to preservation."

Learning from old school video games, then, can also mean learning how to preserve a culture. "I think the Vectrex community shows us that with some dedication and cooperation among people with similar interests," Vectrex veteran Tom Sloper adds Yoda-like, "old software and hardware need not die."

Jorg KochXkoch AT imstall.comX

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com