The Dark Dividend

How does the film industry deal with the breakdown of the Cartesian subject? JJ King goes to Hollywood to investigate and comes to the conclusion that Lynch must shoot PKD

Apparently Philip K. Dick loved the ‘stylish neo-noir’ flick Blade Runner, though it’s difficult to see why. As cliché-establishingly modish as Ridley Scott’s film was, it completely failed to deliver the central Dickian motif: demolition of ontological partitions as trashy human drama. In Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, R. Deckard (geddit? – a clunking cipher for the erector of the Grand Partition itself, R. Descartes) stumbles frequently and painfully into the ontic crevasses that reside ‘between the binaries’ fantasy/real, artificial/natural, mind/body – and, as often as not, fails to crawl out the other side. He’s a replicant, or everyone else is a replicant, and the world inside the book’s ur-VR avatar-environment (which doesn’t – couldn’t – exist in the celluloid Blade Runner) is more ‘real’ than the Real itself, somehow so potent that it bleeds through into, inf(l)ects, everyday existence. It is in this apeshit territory that Dick, by going ‘the whole way’, makes gestures so far unrecuperated (and unrecuperable?) by Hollywood. Count ’em up: in not one Dick-pic to date (Total Recall, Blade Runner, the forthcoming and already Div-Xd Minority Report) is the Cartesian Spectre used as anything but motor for the rattley old action film rollercoaster ride. Even in his over-lauded ‘Director’s Cut’ of Blade Runner, Scott can’t accept Dick’s challenge: his ultimate insinuation (shock! horror!) that Deckard could be a Replicant is the merest widow of Dick’s sustained meditation on nature, mechanism, and the mechanics of being.

And that’s why we’re all sat here waiting for David Lynch to do PKD. Or at least, I am. (Had you thought of it? If not, imagine Lynch-Ubik, or Lynch-Scanner Darkly: now try getting that thought out of your head. I can’t, and am considering starting a letter of petition to the director. Mail me if you’d like to sign up.) Because Lynch has, in Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, committed himself to an examination of our traversals of fantasy in which, as in Dick, the profoundest vortices of human experience are plumbed. In PKD, drugs and insanity often provide the moment of rupture, of ‘going through’, beyond, over. In Lynch, it’s trauma: we witness the phantasmatic writing itself back onto the unbearable real in response to or anticipation of a momentous, often homicidal, event. You can’t help trying to calculate your way out of it (who is ‘the Cowboy’? Why does he portentously tell film director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) how many times he can expect to see him again and then patently fail to appear? How can Lost Highway’s pale little man be in Fred Madison’s house and on his cellphone at the same time, etc?) But such struggles are risible: the whole point’s the utter imbrication of our dream and the world, impossible to prise from each other’s embrace, only suckering more defensively together, cleaving closer, as the world assumes its hostile aspect (the young actress failing in corporatised Hollywood, for example, or the saxophonist unable to satisfy his wife) until in the end they both, world and subject, are mutually, often disastrously, consumed.

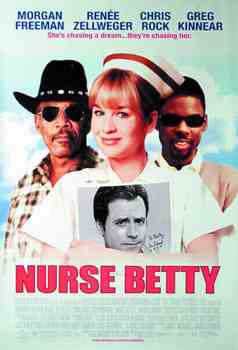

Hollywood’s not exactly comfy with this formulation: rarely does it allow the imbrication of the partitioned, of consciousness and ‘the real’, a life beyond the spectacular. One notable surprise exception is Neil LaBute’s Nurse Betty (2000), in which the central figure, Betty Sizemore (Renée Zellweger), fixates on a hospital soap opera as means of escaping the trauma of witnessing her no-good car salesman husband (Aaron Eckhadrt) being brutally murdered. Betty founds the notion that she is the former fiancée of her soap opera idol Dr. David Rowell (Greg Kinnear), and leaves for Los Angeles to find the hospital where he works as a cardiologist. What’s profound about Nurse Betty is the way it plays cognitive dissonance reduction for laughs: Betty’s so adept at maintaining (and enjoying) her symptom/fantasy that our expectation that it’s about to undergo rupture is constantly and hilariously undermined. Betty becomes a ‘real nurse’ after performing an emergency tracheotomy that she’s learned from the telly; Betty’s flat mate Roza, scheming to burst Betty’s bubble, eventually confronts her with George McCord, the actor who plays Betty’s imagined ‘husband’ Dr David Ravell, accompanied by the soap’s producer and other actors – but Betty’s dream doesn’t go to pieces as it ought: instead, George McCord takes her lovelorn speech as the pitch of a young, ambitious actress wanting to get on the show – falls in love with her – and, reducing his own cognitive dissonance now, reads Betty’s delusional identification with the soap opera as highly committed Stanislavski-school Method. Nurse Betty’s a rare study in the dialogics of phantasm, one which withholds on folding down the partitions until a penultimate, devastating scene in which Betty finally steps onto the set of her soap opera ‘hospital’, and simply cannot find the equipment to maintain her delusion any further. Meanwhile, her ‘real’ husband’s murderers – an aging hit man plus sidekick – are closing in, the return of the repressed, searching for the drugs stolen by her husband. But the hit man, planning his retirement after this one final job, has also begun to project onto Betty his notion of an ideal woman...

Hollywood’s not exactly comfy with this formulation: rarely does it allow the imbrication of the partitioned, of consciousness and ‘the real’, a life beyond the spectacular. One notable surprise exception is Neil LaBute’s Nurse Betty (2000), in which the central figure, Betty Sizemore (Renée Zellweger), fixates on a hospital soap opera as means of escaping the trauma of witnessing her no-good car salesman husband (Aaron Eckhadrt) being brutally murdered. Betty founds the notion that she is the former fiancée of her soap opera idol Dr. David Rowell (Greg Kinnear), and leaves for Los Angeles to find the hospital where he works as a cardiologist. What’s profound about Nurse Betty is the way it plays cognitive dissonance reduction for laughs: Betty’s so adept at maintaining (and enjoying) her symptom/fantasy that our expectation that it’s about to undergo rupture is constantly and hilariously undermined. Betty becomes a ‘real nurse’ after performing an emergency tracheotomy that she’s learned from the telly; Betty’s flat mate Roza, scheming to burst Betty’s bubble, eventually confronts her with George McCord, the actor who plays Betty’s imagined ‘husband’ Dr David Ravell, accompanied by the soap’s producer and other actors – but Betty’s dream doesn’t go to pieces as it ought: instead, George McCord takes her lovelorn speech as the pitch of a young, ambitious actress wanting to get on the show – falls in love with her – and, reducing his own cognitive dissonance now, reads Betty’s delusional identification with the soap opera as highly committed Stanislavski-school Method. Nurse Betty’s a rare study in the dialogics of phantasm, one which withholds on folding down the partitions until a penultimate, devastating scene in which Betty finally steps onto the set of her soap opera ‘hospital’, and simply cannot find the equipment to maintain her delusion any further. Meanwhile, her ‘real’ husband’s murderers – an aging hit man plus sidekick – are closing in, the return of the repressed, searching for the drugs stolen by her husband. But the hit man, planning his retirement after this one final job, has also begun to project onto Betty his notion of an ideal woman...

Of course, Nurse Betty’s not one to go ‘all the way’. We know from the beginning that Betty’s deluded and where ‘the Real’ is at. This ain’t the vertiginous territory of Lynch and Dick, but at least the film’s honest about the ways in which we manage the constant discrepancy between what we imagine ourselves to be and what we are, the petits morts we go through day to day as our phantasy’s perimeters are punctured and reconstituted, is knocked back and rises again like a morning dough. What Nurse Betty shares with Dick and Lynch is this sense that the fantasy cannot hold; stuff bleeds back through from the Real on darkling vectors, borne on strange impulses, negations that remain out of sight. The crucial point of departure from late Lynch, though, and indeed what separates this great director’s film-making ontologically from the rest of Hollywood, is his treatment of the relation between world and mind as a duplex: information is written both ways simultaneously, never (as in Total Recall, The Matrix, or the recent, ghastly, Vanilla Sky) revealing itself as ‘all dream’ (or as in David Fincher’s The Game, all dissimulation, physical conspiracy).

That practice of sealing off the phantasmatic, the scene of the crime, of containing it (as in Star Trek) within a Holodeck, is, of course, a stratagem: what’s outside the deck, however fucked, must be ‘real’. It’s a stratagem that’s anathema to Dick/Lynch, where the moment of the Great Partition’s collapse in a single subject (Do Androids Dream’s Rick Deckard, A Scanner Darkly’s Fred/Bob Arctor, Lost Highway’s Fred Madison/Pete Dayton, Mullhollands Drive’s Betty Elms/Diane Selwyn) is taken as symptomatic of the human condition itself: not a motor to drive an action movie, but the motor which, oscillating through the dark dividend (‘You’ll Never Have Me!’) drives everything we do.

JJ King <jamie AT metamute.com> is a contributing editor of Mute, writer and singer in Snakes

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com