Creation and Interest

Peter Hallward's new book Out of this World: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Creation constructs the French philosopher as a mystic whose ideas, however inspiring, are politically useless. Jason Read, who has made his own claims for Deleuze as an indispensable political thinker, welcomes and contests this new approach

Peter Hallward’s Out of this World: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Creation represents something of an event in the Anglo-American reception of Deleuze. Whereas for years the dominant trend of writing on Gilles Deleuze (and Félix Guattari) has been a series of ‘guides’ and ‘introductions’ to the dense and perplexing philosophy of Deleuze, Hallward’s book is, by contrast, a critical engagement, even a polemic. Hallward argues that Deleuze’s central problem, that of creation, is posed with such an austerity, such a detachment from any engagement with the created world of subjects, histories, and social conditions, that it ultimately dematerialises into an idealistic, or theophantic philosophy. A philosophy in which ‘every individual process or thing is conceived as a manifestation or expression of God or a conceptual equivalent of God (pure creative potential, force, energy, life…)’ (p.4). Hallward’s argument is thus specifically aimed at those who find in Deleuze a philosophy useful for understanding and transforming social conditions. Hallward does not deny that Deleuze’s philosophy is inspirational, just that this inspiration is ultimately misdirected for politics (p.164). As one who has found inspiration in Deleuze’s work, more specifically Deleuze and Guattari’s engagement with Marx, and thus considers Deleuze to be useful thinker for political philosophy, Hallward’s book is an important challenge.1

Image > Seven Days of Creation, Day One

Hallward does not directly engage writers who have attempted to harness some of the force of Deleuze’s writing for a political project, they, (or rather we), are left to the footnotes, instead he engages with the core of Deleuze’s ontology. Hallward thus borrows a principle from Deleuze’s own writing, arguing that every philosopher is animated by just one problem. Despite the apparent heterogeneity of Deleuze’s writings, on cinema, Spinoza, Bergson, Francis Bacon, Proust, etc. there is one central concern underlying these approaches. The various different topics or matters of Deleuze’s writing are simply different cases of a general philosophical problem, that of absolute creation.2 Just as absolute creation can only be grasped from the perspective of actual ‘creatures’, created subjects, modes of living, and works of art, the philosophy of absolute creation can only be articulated through an engagement with multiple creations – the works of cinema, Spinoza, anthropology, etc. Hallward’s interpretation, like Alain Badiou’s, goes against the dominant interpretation, which sees Deleuze as a philosopher of anarchic difference. In arguing for the unity of the problem underlying Deleuze’s writings Hallward includes references to the four books that Deleuze wrote with Félix Guattari (the two volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Kafka, and What is Philosophy?), in doing so he follows a general trend in writing on Deleuze, which has tended to subsume Guattari under Deleuze, recognizing the collectively authored books as simply extensions of problems and concepts in Deleuze’s writing.3 What makes this particularly striking in Hallward’s case is that the fundamental argument of this book concerns Deleuze’s attention, or rather inattention, to the material realities of history, politics, and subjectivity. Politics and history appear most strongly in the books that Deleuze wrote with Guattari. To subsume the collectively authored works under the name of Deleuze, to write of them as a continuation rather than a transformation of problems and concepts begun with such works as the Logic of Sense and Difference and Repetition, is to argue that this difference makes no difference. This is in effect Hallward’s argument in general, however, his failure to address Guattari as a separate thinker ultimately reveals a tendency to force a unity on the works of Deleuze as well as Deleuze and Guattari.

As Deleuze argues (and Hallward cites) in writing on a philosopher one can never begin with a critique: ‘You have to be inspired, visited by the geniuses you denounce.’ Before proceeding to criticize the limitations of Hallward’s book it is necessary to begin with its strengths, which are many. The strength of Hallward’s exposition of Deleuze’s thought stems from its method, focusing on a generic orientation of thought rather than the specific terminology and problem of Deleuze’s various works. Hallward does not view Deleuze’s thought as a progression over time, or passing through the distinct philosophical subfields of ontology, ethics, and aesthetics, but as a unity, as a philosophical event and not a history. The general orientation of Deleuze’s thought is ‘Being is creativity’ (p.1). For Deleuze the task of philosophy is to grasp the process of creation that underlies every created thing. This process of creation is what Deleuze calls the ‘virtual’, a word that is deceptive since it suggests what is artificial or less real. For Deleuze the virtual, even though it cannot be represented or grasped, is reality. It is more real than the fixed, the finite, the actual. This can be seen with respect to time: even though the present appears to be real, it is necessarily fleeting and ephermeral, the “now” which passes at the moment it is uttered. What is real is not the present, but the past, the unpresentable totality of time. What can be said of time can be said of reality in general, it is not the present thing or object that is real but the process that brings them into existence. ‘In reality it is the virtual, not the actual, that is creative or determinant’ (p.33).

The strength of Hallward’s analysis is in grasping the relation between the actual and the virtual, as the relation that underlies the various dualisms that litter Deleuze (and Guattari’s) work: active/passive, paranoid/schizophrenic, movement image/time image, etc (p.82).4 Deleuze and Guattari’s various dualisms, which are repeatedly invoked, and then dropped, as the furniture that Deleuze and Guattari are constantly rearranging, are often read as the positive and negative terms.5 The positive term of Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis is that which is closest to, must open to, the virtual creation that traverses it. However, Deleuze (and Guattari) insist that the positive term is inseperable from the negative term, deterritorialization cannot be dissociated from reterritorialization. Absolute creation only exists in relation to its opposite. ‘…Only an absolute virtual or non actual force creates, but it only creates through the relative, the actual the creatural’ (p.96). Any attempt to grasp the virtual without passing through the actual, to grasp the absolute process of creation without relative figures, concepts and desires leads to ‘chaos’ (p.130). The virtual is primary, but is not self sufficient, as with Spinoza, substance can only be grasped through the modes.

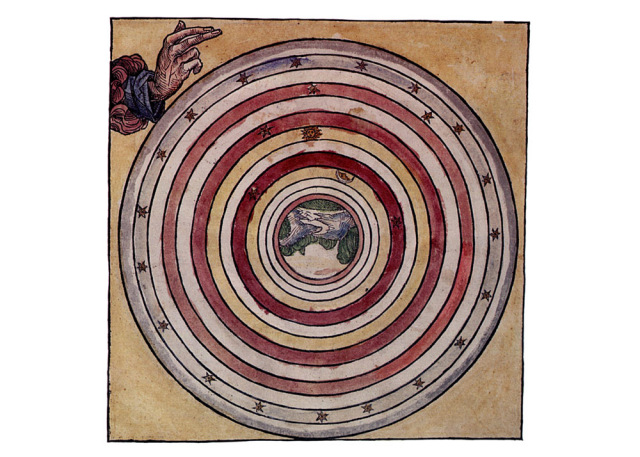

Image > Seven days of Creation, day FourThe primacy of creation over the created, of the virtual over the actual, leads to the following problem: ‘although there are only creatings, these can give rise to creatures which then get in the way of creation. There are only creatings, but some of these creatings give rise to the unavoidable illusion of creatural independence’ (p.55). In other words, why do we fail to see the virtual creation, instead taking the actual ‘creatures,’ created things, as reality? If all of the philosophers in Deleuze’s tradition of ‘minor thought’ have a similar perspective in which a process, natura naturans or the striving of the conatus for Spinoza, creative evolution or the spiritual memory for Bergson, the will to power in Nietzsche, is more real, closer to the creative process of being, they all also have different answers to the critical question as to why the process of creating ‘alienates itself’ in separate created things. Spinoza’s critique of superstition is not the same as Bergson’s critique of the fallacies of natural perception, which in turn is not the same as Nietzsche’s critique of ressentiment. Deleuze’s writing cuts across these different writers borrowing different aspects of their ontology and criticism. Given that these different writers have different ontological and epistemological commitments the question arises as to which is dominant, or how this specific ‘minor’ tradition is articulated into a philosophical system. For Hallward it is Bergson’s response to this question that is dominant over Deleuze’s thought. Bergson demonstrated how it is in our practical interest to perceive the world in terms of discrete objects, delineated movements, and distinct moments of time (p.17). As much as being is creation, we are created by the forces of evolution to necessarily mis-recognize this process. The fundamental mis-recognition that defines our existence is in Bergson’s version a fact of nature, a fact of life. As Hallward writes: ‘The way we live obscures the reality of life’ (p.26). This is in keeping with Hallward’s interpretation of Deleuze as a vitalist. What is striking, however, is that the other philosopher’s give an answer that is less a matter of nature, than of history and society. This is most striking in Deleuze and Guattari’s interpretation of Marx in Anti-Oedipus. As Deleuze and Guattari write:

Let us remember once again one of Marx's caveats: we cannot tell from the mere taste of the wheat who grew it; the product gives us no hint as to the system and relations of production. The product appears to be all the more specific, incredibly specific and readily describable, the more closely the theoretician relates it to ideal forms of causation, comprehension, or expression, rather than to the real process of production on which it depends.6

Even though they do not use the term, Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis here comes close to the concept of ‘reification’: the transformation of a process into a thing, an object. If the general problem of Deleuze’s philosophy is how a creative process becomes misrecognized as a thing, as a subject or object, Deleuze’s work with Guattari, most notably Capitalism and Schizophrenia , introduces an analysis that locates this problem within a history of production, and the mode of production. As Deleuze and Guattari argue each regime of social production is confronted with the same problem: how to code or regulate the flows of desiring production. In other words, how to suppress and contain the creative power that underlies any social formation. Deleuze and Guattari’s answer, which takes the form of a sustained polemic against psychoanalysis and an engagement with anthropology and political economy, is that a social formation does this by assigning desire particular interests and aims, coding it, that is by subjecting it to a particular form of subjectivity and a particular object. We do not enter into the world always already oriented towards a particular (impossible) object, as psychoanalysis claims, but rather it is the process of history, a matter of micro-politics, that assigns an object to desire and interest to a subject.

Interest is an important term in Hallward’s criticism. It underlies his emphasis on a Bergsonian anthropology, or natural history, in defining Deleuze’s critique of everyday consciousness and subjectivity. Interest is what individuates us into subjects, and it is interest that carves up the world into discrete objects and experiences. ‘The domain of the actual is thus subordinated to the requirements of interest and to the actions required for the pursuit of interest’ (p.31). Not incidentally interest is also central problem of Badiou’s political philosophy of the subject. For Badiou ‘interest’ is fundamentally animalistic, the struggle for survival is what we have in common with all living things.8 It is against this animalistic struggle that the subject is constituted as a subject of truth, a truth whether it is amorous, artistic, or political, is by definition something disinterested, or not in our interest. It is something that we risk our life and existence for. Moreover, Badiou argues that it is in the name of ‘interest’ that every political process is interrupted and diverted, the subject of truth is reduced to a subject of interest and politics becomes nothing more than the struggle of interests and opinions.9 Deleuze and Guattari also argue that interest defines a limited and truncated aspect of human existence. However, for Deleuze and Guattari, interest is not the residue of a purely animalistic existence, rather it is the product of a particular social formation.

Once interests have been defined within the confines of a society, the rational is the way in which people pursue those interests and attempt to realize them. But underneath that, you find desires, investments of desire that are not to be confused with investments of interests, and on which interests depend for their determination and very distribution: an enormous flow, all kinds of libidinal-unconscious flows that constitute the delirium of this society.10

Interest is always oriented towards the goals and desires of a particular society, in our society towards the demands for money and consumer goods while in a feudal society it would be oriented towards prestige and honour, it is for this reason that Deleuze and Guattari argue that interest can never be revolutionary. In contrast to this desire is by definition revolutionary, it is the virtual creative power that exceeds any social formation. Both Badiou and Deleuze and Guattari have articulated a politics that is against interest, a redemption from interest. They differ not only in terms of what they oppose to interest, for Badiou it is truth and for Deleuze and Guattari (at least for their writing of the early '70s) it is desire, but also in how they understand interest. For Badiou it is a fundamentally animalistic aspect of existence, while for Deleuze and Guattari it is the product of a particular social formation. For Badiou interest is an anthropological problem, having to do with the struggle between the human animal and the immortal truths that we are capable of, while for Deleuze and Guattari it is a problem of the socio-political order. It is the conflict between the particular form of subjectivity a social formation requires and the virtual powers that exceed any social formation.

To return to Hallward’s criticism of Deleuze, it is possible to say that he has imposed some of Badiou’s categories on his interpretation of Deleuze (making Deleuze a ‘bad’ Badiou), but more importantly he has overlooked the rather substantial changes within Deleuze’s thought. He has subordinated the history of Deleuze’s thought to a unity of becoming, effacing the actual changes in grasping the virtual creation. These changes relate not only to Deleuze’s collaboration with Guattari, but to his eventual politicisation. His engagement with the realities of capital and the state. This engagement modifies substantially the general problem of Deleuze’s thought. In Deleuze’s writing with Guattari, at least the two volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia, the actual is no longer a byproduct of our limited human perception, an effect of evolutionary adaptions, but an effect of socio-political strategies of control. Thus, it is not so much that Hallward argues against the political dimensions of Deleuze’s thought, his very approach effaces it from the beginning. In order to assess the relevance of Deleuze thought for politics it will be necessary to at least acknowledge the effects politics had on Deleuze's thought: the events of May '68, the work with Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons, with Félix Guattari, and the debates with Foucault. Despite this criticism Hallward’s book presents substantial questions for any reader of Deleuze, or contemporary philosophy. These questions (which cannot be dealt with fully here) have to do with the relation between ontological and political commitments and ultimately with the meaning of ‘materialism’ in contemporary philosophy and politics: a question which began with Marx’s first thesis on Feuerbach and continues through contemporary debates on ‘immaterial labour’.11 Hallward’s Out of this World puts to an end the introductions to Deleuze, and begins the process of debate.

Peter Hallward, Out of this World: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Creation, London, Verso, 2006. ISBN: 1844675556N

NOTES

[1] See my The Micro-Politics of Capital: Marx and the Prehistory of the Present.

[2] On this point Hallward is complete agreement with Badiou’s critique on this point. The heterogeneity of topics is only apparent. While it is true that Deleuze always begins from a specific case, rather than a general principle, this case is only a ‘case of' a general problem, that of creation. ‘The rights of the heterogeneous are, therefore, simultaneously imperative and limited’ [Deleuze:The Clamor of Being, p. 15].

[3] The question of Félix Guattari’s influence on the collectively authored works cannot even be addressed in the Anglo-American world due to the paucity of translations. However, the recent publication of books such as Anti-Oedipus Papers addresses this gap.

[4] Hallward agrees with Badiou that despite the fact that the distinction between active and passive seems preeminent in Deleuze, underlying his interpretations of Spinoza and Nietzsche, this dualism is itself simply another version of the far more central dualism of virtual/actual. [Deleuze: The Clamor of Being, p. 34].

[5] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p. 20.

[6] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus, p. 24.

[7]An early essay by Hallward titled ‘Gilles Deleuze and the Redemption from Interest’ indicates how much Hallward focuses on ‘interest' as the defining feature of worldly existence.

[8] Alain Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, p. 46.

[9] As Badiou writes, ‘…there is the idea that interest lies at the heart of every subjective demand. Today, this continues to be the principle and perhaps only argument used in favour of the market economy' [Metapolitics, p. 133].

[10] Gilles Deleuze Desert Islands and other texts p. 262. The use of the terms ‘interest’ and ‘desire’ relates to a short period in Deleuze and Guattari’s works, generally in the writing of Anti-Oedipus and the interviews and essays from that period. The terms disappear in A Thousand Plateaus, but not the problem. It reappears in relation to the difference between ‘majorities’ and ‘minorities’. Maurizzio Lazzarato argues for the fundamental continuity of these problems in Les Révolutions du Capitalisme.

[11] Marx first ‘Theses on Feuerbach’ states. ‘The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialism – that of Feuerbach included – is that the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively. Hence, in contradistinction to materialism, the active‘materialism’ after Marx must begin with paradoxical status of Marx’s relationship to materialism. [The Philosophy of Marx, p.25] side was developed abstractly by idealism – which, of course, does not know real, sensuous activity as such.’ As Etienne Balibar argues Marx’s materialism is a materialism without matter, what is material is not an object, such as the body, but transformative activity itself. Any discussion of the problematic status of 'materialism' after Marx must begin with paradoxical status of Marx’s relationship to materialism. [The Philosophy of Marx, p. 25]

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Badiou, Alain. Deleuze: The Clamor of Being, translated by Louise Burchill.Minneapolis: Minnesota, 2000.

Balibar, Etienne. The Philosophy of Marx. Translated by Chris Turner. New York: Verso, 1995

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia,translated by Robert Hurley et al. Minneapolis: University of MinnesotaPress,1983.

Badiou, Alain. Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, translated by PeterHallward. New York: Verso 2002.

Badiou, Alain. Metapolitics, translated by Jason Barker. New York: Verso 2005.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, translated by BrianMassumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Hallward, Peter. ‘Gilles Deleuze and the Redemption from Interest’, Radical Philosophy 81, January/February 1997.

Hallward, Peter. Out of this World: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Creation. New YorkVerso, 2006.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. Les Révolutions du Capitalisme. Paris: Empêcheurs de Penser enRond, 2002.

Marx, Karl.‘Theses on Feuerbach’ in The German Ideology. Edited and Translated byC.J.Arthur. New York: International, 1970.

Read, Jason, The Micro-Politics of Capital: Marx and the Prehistory of the PresentAlbany: SUNY, 2000

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com