Creating the Commons

Andrew Losowsky looks at the new Creative Commons licensing structure and asks who is on either side of the ‘middle ground’ which the project assumes?

New licences are trying to add important flexibilities to the rights of creators. Following the open source model, a Copyleft conference in Paris in 1999 led to ‘Art-Libre’, one of the first socialist manifesto-cum-licences aimed at online artists. But under French law, Art-Libre created little more than a public domain in which derivative works could never be used for profit. A more significant moment came last December, when the first free licences were made available by the Creative Commons project [www.creativecommons.org ] – which framed what the project initiators called a ‘some rights reserved’ licence. The licence is machine-readable and is applicable to most global definitions of copyright.

‘The idea was to take the unnecessary legal friction out of everyday online interactions,’ says Creative Commons’ executive director, Glenn Brown. For the first time, copyright wasn’t an all-or-nothing affair. The artist retains copyright, but within one of several different licences, which have the flexibility to decide if you want to surrender all rights or only withhold some, such as the right to attribution or commercial use. Moreover, its website simplifies the terms in easy-to-read shorthand as well as legalese.

‘Creative Commons lets you express a preference for a more measured and generous approach to most copyright issues,’ says Brown. ‘And apart from the practical advantages, it’s also a way of raising your hand and saying, “I believe in another way,” and then acting on it. There are almost no other outlets for such creative civil obedience in the world of copyright today.’

Thousands of people have adopted the licences over the last few months, for everything from holiday snaps to home-made music. In January, a watershed was passed when the outreach coordinator of the Electronic Freedom Foundation and net celebrity Cory Doctorow simultaneously released his new book, Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, with a major sci-fi publisher and also for free online, attaching a Creative Commons licence to its download. The book hit the Amazon top 300 for sales. Meanwhile the downloads from his site [www.craphound.com ] totalled more than 90,000 in the first month – far exceeding the initial print run. ‘I couldn’t be more stoked,’ he says.

Others, however, are a little less enthusiastic. ‘As far as I can tell, there is no remedy [in the licences] for misuses of my work,’ says Jonathan Delacour, a web consultant and photographer based in Sydney, Australia, with his own weblog [weblog.delacour.net ]. ‘What’s to stop someone overlaying racist captions on my photographs if I give up my right to them? How am I to respond when the pictures I took at a Jewish funeral appear as illustrations in an anti-Semitic diatribe? Not only has my artistic intent been subverted, but I have also allowed myself to be portrayed as an anti-Semite. And I can’t change my mind, either - licences apply worldwide, last for the duration of the work, and aren’t revocable.’

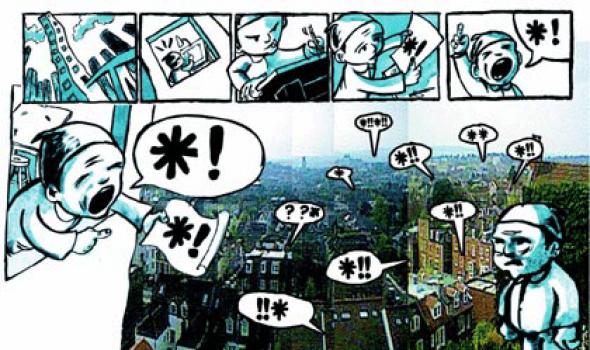

Delacour dismisses those who have adopted Creative Commons licences in an attempt to open up further collaboration or to encourage derivative works. ‘I think it is naive to believe that allowing Adam to copy Beryl’s work will result in a flowering of creativity. It won’t,’ he says. ‘All that will result is a plethora of mediocre derivative works and an occasional derivative masterpiece - in other words, the normal process of art production (in which the dross overwhelms the gold) will be reproduced on a hugely magnified scale.’

Others believe that adding a licence into the creative chain represents a bureaucracy that can come between an artwork and its usage. ‘Licences generally feel too much like legal documents,’ says Takashi Okamoto, an artist who runs the Mud Pub online community [www.mudpub.com ] and creates works using online imagery. ‘As an artist that uses open source software, I’d like to extend the idea of open source to art and if someone looks at my work and feels there’s an idea that they can investigate, I want them to do whatever they want to do. I don’t want to force them to read a licence document and tell them what they can and can’t do.’

Creative Commons attempts to cater for a middle ground: creatives who believe in free distribution and collaboration but don’t want to surrender all their rights. Many bloggers (unsurprisingly) have adopted the licences, and weblog software such as Moveable Type has started to include Creative Commons options in its metadata provisions. As more artists adopt the licences for their work, search engines may soon include the option of searching for works that you can legally collaborate with, or use on a not-for-profit basis.

‘Clearly there is a disconnect between what the law allows and what many people think is a legitimate and creative use,’ says Glenn Brown. ‘But by adopting a Creative Commons licence that allows such uses, an artist is taking the stand that they think mash-ups and other creative reworkings should be encouraged. It’s not going to change the law, but it certainly makes a statement.’

Andrew Losowsky <andrew at losowsky.com> lives in Barcelona and is supposed to be writing a novel. See his weblog, [http://barcablog.com ]

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com