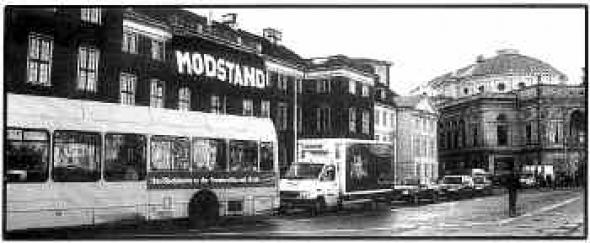

Counter-revolutionary Times

As Europe’s swing to the right prompts some commentators to lament the passing of social democracies, Mikkel Bolt insists that we should resist the temptation to fall for such counter-revolutionary conclusions. Taking Denmark as a case study, he has some advice to offer leftists and artists alike 'There is something rotten in the state of Denmark’Hamlet, William Shakespeare

Some friends have been writing to me recently. Having believed what they’ve been reading in Le Monde or on the net, they thought that something was really going on over here. Others have been eagerly expecting clashes between the new right wing government and Danish artists similar to those in Austria, but so far no one has done or said much. Well, some artists did protest when the new minister of cultural affairs announced cuts in the cultural sector, but few of them have been willing or able to connect the attack on culture with a broader take on the situation. As for the traditional left in Denmark, so far no one has been able to analyse either the local or the global situation. Some leftists believe it is better to duck out the crisis when, in fact, it is now clearly crucial to provide a better analysis and to defend against reformism.

But it is true that the Danes have, as recently as 20 November, appointed a new government whose politics are racist and ultra-populist. The new government is cutting down in development aid, tightening the laws on immigration, closing the Centre for Human Rights and cutting funding to the education sector. This probably sounds like a drastic change in the situation in Denmark, but it is necessary to point out that the Danish social-democratic government itself prepared the way for this xenophobic backlash by nationalising the working class. There is only a small step from a nationalised social-democratic working class to the racist rightwing working classes currently sweeping Europe. It was a smooth transition from the former social-democratic minister of the interior, Karen Jespersen, to the newly appointed immigration minister, Bertel Haarder. As such the European social-democratic parties bear responsibility for the rise of Blut und Boden politics and, as such, have failed miserably.

The situation is indeed complex and art might have difficulties intervening in society’s communication systems and negotiating its political engagement because, post September 11, no one knows where the political is heading (it is not possible to deduce anything so we must start hypothesising). This situation makes it easy for politics to recuperate art but difficult for art to appropriate politics. A difficulty that has been increasing ever since the Situationist International dissolved itself because of the impossibility of appropriating politics and converting political messages. (As, for instance, it tried to do when it placed a copy of a statue of Charles Fourier at Place Clichy in 1969). As such, this is a difficulty that has to do with the spectacular nature of politics – for instance, the fact that regression can appear dynamic in politics is a result of this dangerous emphasis on visibility.

Some are of the opinion that we must separate art from politics and form a political forum in the style of the Collectif Anti-Expulsions in France, working to prevent deportations of immigrants. This would mean refraining from commenting on the political agendas of the government, political parties and organisations in favour of intervening practically in concrete cases where immigrants are being expelled. Concrete ‘political’ actions, similar to the ones the Collectif Anti-Expulsions carries out, would keep artistic experimentation alive without practicing a uniting context-text (as, for instance, the Situationists did with the situation). The attempt to work with two or more texts – a practical political one and an artistic experimental one – instead of a uniting context-text, would mean that art could go on experimenting on its own. The other solution would, of course, be to try to locate a grey zone between art and politics, create local holisms of contextualisation and strive after political effects. In the present situation this solution seems appropriate but requires a heavy dose of theory, practical know-how and disregard for the art historical tradition unless art should just provide a pious foil to political events. A prerequisite for this fusing of art and politics toward developing appropriate practical interventions within the shifting complexity of the historical situation would be to gain as correct an understanding of ‘reality’ as possible. An enterprise of great difficulty but nonetheless necessary in the present situation. And also an enterprise already well underway in Italy, Austria and other parts of Europe where groups like N+1 are trying to formulate a radical critique of the present world situation without remaining attached to nostalgic forms of politics. We are faced with a tremendous project of critiquing the populist and fascist turn in Europe while also avoiding the problematic short circuits of the ouvrierist tradition (the desire for action remains too attached to a notion of subjectivity) and the notion of alienation (people are not alienated even though the economic relations are difficult to see through, they are dependent upon or subsumed by capitalism, which is not the same as being alienated) while working towards the long term abolition of money and capitalism.

Because there is surely another way out of this situation than the preventive counter-revolutionary one we are witnessing gaining hegemonic status right now – whether in Afghanistan, Israel, Argentina, Austria, France, Italy, Denmark or elsewhere. The revolutionary preparedness that was becoming slowly visible is now being converted into totalitarian political and economic solutions of a nationalistic character. We must not let the counter-revolutionary movement with its rejection of multi-culturalism, its longing for ‘purity’, its nostalgia for a mystical world of racial homogeneity and clearly demarcated boundaries of cultural differentiation, its celebration of the ties of blood and history over reason and common humanity, take over the dynamic in the present political-economic transformation.

Mikkel Bolt <kunmbr AT hum.au.dk> is an art historian and editor of Mutant

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com