From Coca to Capital: Free Trade Cocaine

The War on Drugs, together with unequal free trade legislation, have provided first world junkie-capitalism with the liquidity and 'bio-tools' it needs to drive its delusional and unsustainable growth - writes John Barker

In 2009, the Observer newspaper reported the assertion made by the United Nations illegal-drugs ‘czar', Antonio Maria Costa, that he had seen evidence that the proceeds of crime were the ‘only liquid investment capital' available to some banks on the edge of credit crunch collapse, and that a majority of the estimated $315 billion drugs profits had been absorbed into the legitimate financial system.i He was, needless to say, coy about which banks had benefited, revealing only that the evidence came from intelligence sources and state prosecutors. But what he did do was blow away the myth that drugs profits are laundered solely through ‘dodgy' offshore concerns.ii Ben Ehrenreich reminds us that such coyness is unnecessary: writing of the Mexican drugs business he notes:

Investigations in the USA and Mexico have implicated Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Citigroup, HSBC and Santander (among others) in cartel-related money-laundering. Sr. Costa's observations as to the significance of criminal money to the global economy also does not prevent him from being a hard-line exponent of the ‘War on Drugs', a ‘war' without which those profits would not be realised and ready for use as that ‘liquid investment capital'.

Image: Mexican paramilitaries patrol the Sinaloa mountains

Cocaine is now the illegal drug industry's most financially significant commodity subject to this ‘war'. At the same time the dynamics of the very capitalism which has recently needed that injection of liquid capital, regardless of its origins, create the conditions that make coca growing the most rational economic choice for many small-scale Andean farmers, while it is also these farmers who are most penalised by this ‘war without end'. Instead, cocaine is not just functional to the creation of private capital, but the war against it is useful ideologically, and for the selective repression it requires and entails both internationally and internally. This involves notions of ‘backwardness' in the case of small-scale farming, and of racial character defects of particular consumers. In the USA specifically it has played a large part in creating a self-perpetuating and racist ‘prison-industrial complex'.iii

The drug is also functional to capital as an aid to the ‘productivity' of certain kinds of labour in what are called the creative and financial industries. The capacity of cocaine to induce both a promiscuous enthusiasm and controlled perseverance is especially suited to such project-defined work. In recent years the demand has increased still further as other areas of work demand worker performance.iv This reality, however, cannot be given any official or academic recognition.

The 16th century pragmatism of the Spanish King Philip on the matter of coca, when he overturned the Catholic church's ban on it in the name of labour productivity, is ideologically impossible now, except within the indigenous peasant movement in Bolivia which has fought to make it legal.v The Bolivians, unlike the king, are fighting for the recognition of its cultural significance and a properly scientific appreciation of its qualities.

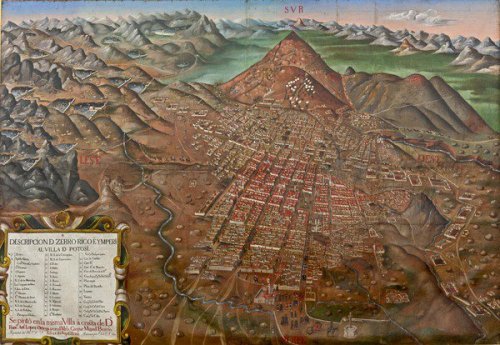

Image: Founded as a mining town, Potosí became one of the largest cities in the Americas in the 17th century

Bring Forth the Backward

It is hardly coincidental that the major producers of the war-targeted cocaine, heroin, marijuana and cannabis are countries designated as ‘under-developed', or what have also been called ‘backward' areas of the world. In most periods of colonialism words like ‘savages' depicted ideologies of racial superiority. After the Second World War, a new language emerged, articulated in the inauguration speech of US President Harry Truman in 1949, and reasserted in John F. Kennedy's Alliance for Progress. The institutional context of Truman's speech was the birth of the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions. In it the ‘moral' and 'civilisational' superiority of the USA, which previous presidents had proclaimed, was now manifested as its science and technology.vi

Just a year later in 1950, one Howard Fonda, a banker and president of the US Pharmaceutical Association, led a UN Commission to study coca. His study of Aymara and Quechua people (with one translator) concluded that coca chewing was the cause of poverty in the Andean countries because it lowered the capacity to work, which was in flat contradiction to the seriously concerned opinions of the Conquistador exploiters of silver mines. Apart from its denigration of two ‘backward cultures', Fonda's report was clearly self-interested and unscientific, ‘plagued by prejudices, unfounded speculation and third-hand sources.'vii

This did not prevent it being ratified by the World Health Authority in 1952, and the power of this self-interested prejudice became ever clearer with a refreshed version of the Truman rhetoric, namely President John F. Kennedy's Alliance for Progress. Its existence was proclaimed in 1961, and in the same year the United Nations' Geneva Convention on Drugs outlawed coca except as a flavouring agent.

Despite its powers of enforcement, capitalism cannot tolerate other socio-economic modes of living. They are an affront. And in the case of opium and coca, the fact that they have been traditionally and uniquely produced in ‘backward' areas makes them inherently bad. In this narrative we don't hear that cocaine was actually synthesised by a European using those very same ‘industrial and scientific techniques' Harry Truman boasted of. The affront is that its production still depends on the coca leaf. Equally, the 1961 Geneva Convention On Drugs (which proclaimed that the total prohibition, and therefore eradication, of chewing coca should be completed in 25 years and made cocaine Public Enemy Number One), had a get out clause. According to Article 27, ‘it is allowed to plant, transport, market and possess coca leaf in the quantity necessary for the production of flavouring agents.'viii This, as Jorge Hurtado describes, was solely in the interests of the Coca Cola Corporation.ix

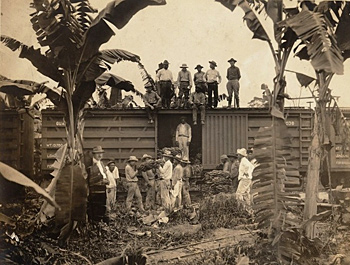

Image: United Fruit Company in Guatemala in the early 1950s

At this time ‘wars' were monopolised by the Cold War. 1961 however, marked the beginning of what in our age has become one of many thematically-defined Wars: on Drugs, and subsequently on Terrorism, and now - grotesquely - on Poverty and on Cancer. It is ironic that when Realpolitik intellectuals routinely talk of a ‘new Middle Ages' in the context of ‘underdeveloped' countries, their masters talk not just of wars, but pitch drug czars against drug Barons.x A minority of academics and various people who have worked in drug enforcement agencies have talked of the ineffectiveness of this ‘war', and the many ways in which it is counter-productive.xi Why then its continuation, which depends on the continued illegal status of cocaine, and which has not altered the demand for the drug in a performance-oriented world of capitalist work?

‘An Unfortunate Style of Crop Diversification'

It's not hard to see that there are powerful interests at work in the maintenance of this particular war without end. More than that, globalised capitalism creates and re-creates the conditions which make the growing of coca and transportation of cocaine the only rational options for people in the poorest parts of the world. ‘Rational' in the neoliberal sense, as in individualised and calculating; how ‘human nature' is, and ought to be. The emphasis on the virtues of international ‘free trade' has increased both the necessity and opportunity for different peoples to become involved in the cocaine business. The explosion of opportunity is obvious: exponential growth in international trade, proclaimed as an absolute virtue, with its millions of containers, air flights, penetration of new markets and so on, has created many more possibilities for the transportation of cocaine across borders. At the same time other distinctive characteristics of ‘global capitalism' have provided motivation both for growers and transporters:

1. Its intolerance of anything but itself, and of particular indigenous, non-capitalist cultures means, materially, an intolerance of non-capitalist agriculture whether it involves communal land or peasant (campesino) farming.xii

2. International trade is not free. The assumption of equal power amongst market participants is an obvious lie, and especially so in agriculture. While the West preaches, it has consistently used subsidies, export credits and import quotas to serve its own interests. Combined with an imposition of its version of free trade and its version of development as monoculture crops for export, it has destroyed a whole class of small farmers producing food for their own markets. This has been most spectacular in the case of Mexico since the imposition of NAFTA; something clearly foreseen and opposed by the Zapatista movement.

3. Risk-taking by capital, as creating the optimum allocation of resources, has been its self-proclaimed virtue. The banking crisis of the present period has made a mockery of this claim, and the risk has been passed on to the people of the world at large. This has been the experience in agriculture for far longer. The power of wholesale oligopolies, and increasingly of supermarkets, has shifted the risks of small-scale farming for export still further onto the farmer. Already faced with the vagaries of the climate, and the possibilities of interest rate and fertiliser price increases, there are now systems of Supply Chain Management made possible by IT developments, which give all power to the buyer.

4. Where quotas favourable to small-scale producers did exist, corporate lobbying - in this case by Chiquita - has undermined them so as to boost its own levels of exploitation in the plantations of Ecuador. This follows a pattern started in the Reagan-Bush era of undermining commodity price agreements which offered some security to farmers. At the same time, in the case of sugar for example - produced in Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia as well as the Caribbean - the USA imposed import quotas. It prompted US Congressman Thomas J. Downey to write an incredibly frank letter to The New York Times on 20 September 1989 which addressed this matter. Just as President George Bush Sr. was announcing an $8 billion solution to the ‘drug problem' , the Congressman pointed out that in the period 1983-9 imports of 200,000 tons of sugar from these countries fell to less than 85,000.xiii The trend was already apparent in 1987 when he notes that State Department officials writing in the Washington Monthly warned that this would lead to ‘an unfortunate style of crop diversification.'

Trade Routes

Links then between coca production and the politico-economic realities of the capitalist world are not paranoid fantasy. On the other hand, I do not intend to make anything of the well-known US green light to cocaine smuggling at the time of the Contra war of destabilisation in Nicaragua; nor to claim that these links are always Cause A of an inevitable Result B. As a major cocaine trade route associated with extraordinary levels of violence, Mexico has to deal with its location, history and experience of politically controlled smuggling. But the business has seen an exponential increase since the imposition of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement). This ‘free trade' agreement meant, in practice, that smuggling became easier due to the increase in cross-border trade transport. The de-regulation of the Mexican financial system also made money laundering that much easier. As subsidised American corn flooded the market, over a million small farmers and another 1.4 million dependent on the agricultural sector lost their livelihoods. Monthly incomes for self-employed farmers fell by 90 percent between 1991 and 2003.xiv Ehrenreich notes that in Bandiraguarto, people ‘have little choice but to become narcos because there is so little other work, and with a government that largely doesn't care and a formal economy that takes pity on no one.'xv

Image: Mexican coca farmers

Mexico's history made it an ever more important trading route following increased drug police activity in the Caribbean, which had previously been such an important entrepôt with links to markets in the US itself. In the Caribbean, with its convenient location and a history of political gang violence, the shift in the political economy of both sugar and bananas also nudged it further toward the cocaine business. In their case, effective lobbying from Chiquita via the Americans at the WTO forced the EU to cap its preferential trade terms for Jamaican bananas. Its markets are now full of subsidised American produce that local farmers cannot compete with. It leaves Jamaica and other islands with the choice of tourism or cocaine. To repeat, these are not A-to-B explanations as to why it became such an important place in the transnational drugs business, but it is important to make the link when the capitalist ideological apparatus is as focused on a ‘de-linkage' by which it is able to selectively moralise or produce psycho-social explanations of its own, as with the ‘failed state' label. The Nicaraguan Miskito coast has also emerged as a perfect entrepôt between the Northern Colombian coast and Mexico. Here too specific government neglect and the experience that must have been gained in the period when Miskito communities supported the Contras in the 1980s destabilisation war, made it a natural place to make drug business connections. But it is also a place of deep poverty and high unemployment, and this in a country where banana pickers are the lowest-paid of all in Latin America.

West Africa has now emerged as a main entrepôt for the transportation of cocaine into Europe. Guinea-Bissau, was a favourite in the circles of ‘failed state' discourse and voyeuristic-moralising journalism. It has since been replaced as a favourite for cocaine transporters by Senegal with its advantage of better roads and telecommunications. 3,120kg of cocaine were seized off its seaboard in 2009. Again, its geographical location and previous history of illegally smuggling human beings into Europe in satellite-equipped canoes (‘pirogues'), until that business moved further South, make it highly suited to the cocaine trade.xvi However, there is also an element of ‘failed state' theory in western accounts, ‘unmonitored coasts, poorly paid officials, porous borders and booming informal markets.'xvii No reference is made to the destruction of local fishing by bottom trawl-net fishing - in which around 75 percent of the catch is discarded dead - as well as un-regulated factory ships which, flying ‘flags of convenience', enforce slave-like crew conditions.xviii The real historical context is that Senegal's most prosperous year was 30 years ago.

Coca, the Safest Bet

Coca just grows, it's a weed. Farmers don't have to worry about markets and diseases. It always gets a good price.

- Liliana Ayalde, USAID 2004

The very first mission from the post-war western world, following Truman's development of the backward speech, was Colombia. Headed by Lauchlin Currie, it was the first World Bank ‘comprehensive economic survey mission' and began on 30 June 1949. On 19 August the country received the first World Bank funding, which was an agricultural machinery project loan. This perfectly reflected Truman's promise to bring technological skills to the backward. Further World Bank credits followed in 1954 and then again in 1966, this time to foster large-scale cattle ranching. Nowhere was attention given to the chronic shortage of land for small farmers in a country where 60 percent of agricultural land is owned by 0.5 percent of the population. Then, as Héctor Mondragón describes at the time of the Clinton Presidency, and after years of FARC activity, ‘the World Bank granted an induction credit of $1.82 million to fund pilot projects and a Technical Unit, with the goal of "preparing" a complete support project for "market-based agrarian reform"'.xix This ‘reform' is an object lesson in the dangers of becoming indebted. Mondragón describes it as such:

Here's the paradox: the beneficiary of the subsidy program for land purchases (in the original scheme) becomes a real ‘loser' who receives an unpayable credit that leads him to lose the land and to be registered in the data bases listing people who are in arrears. In addition to no longer having land, he can no longer receive any kind of credit.

In the hands of the Pastraña government as of 1998, ‘it didn't seek to strengthen the campesino (peasant farmer) economy but rather sought the subordination of campesinos and the handing over of their property to large farms.' With a sleight of hand characteristic of contemporary capitalism, those whose ‘development' policy entails the ‘maintenance and consolidation of large rural properties', dismiss real land redistribution as ‘obsolete' or ‘antiquated'. And this, Mondragón argues, has pushed campesinos beyond the ‘agricultural frontier' and into the jungle to grow illicit crops. These circumstances have been further augmented by the dynamics of ‘neoliberal' capitalist globalisation.xx

Image: US funded Colombian paramilitaries sent to curb drug smuggling and combat left wing insurgencies

In 1990 Colombia's food imports accounted for just six percent of GDP. By 2004 it had amounted to 46 percent, with an emphasis instead on large-scale production of African palm, pineapples and cocoa. Given the history of coffee production, and indeed of many instances of export monocultures in the ‘backward' world, this is likely to end in tears. In 1997 the price of organic coffee was $1.34 a kilo and by April 2004 it was down to $0.89.xxi It was a process that started with the July 1989 dissolution of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) negotiated in 1975; a period when the articulated possibility of a New International Economic Order on the back of OPEC's success, was flattened by the politico-economic bulldozer of neoliberal policy for which such commodity price agreements, which had given producers some security of income, were denounced as ‘ideological'.

President George Bush Sr. talked awareness-talk on the coffee-coca nexus at the very same time as Congressman Downey was explicitly linking coca growing to US sugar policy. On 28 September 1989, with a team including drug ‘czar' William Bennett, he met with Colombia's President Barca to praise him for his ‘heroic fight' against the drug trade and said he was prepared to resolve problems with the now hobbled coffee agreement. In fact he did not resolve it, so that by 2003 Gabriel Silva, the President of the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia, was saying, ‘we've seen some marginal areas of the Colombian coffee region farmers switching to illegal crops.'xxiiBy this time the breaking of the Agreement had been cemented by the power of the coffee-buyer oligopoly (consisting of Sara Lee; Kraft; Procter & Gamble; and Nestlé). This is part of a trend where risk is imposed still further on the farmer. In this instance the ICA was replaced by the supplier-managed inventory (SMI) system whereby the supplier becomes responsible for maintaining the stocks used by the purchasing firm even if the stocks are held at a port in that firm's country or its own storage.xxiii

In all these circumstances the obvious irony is that the crop with least income risk is the illegal one, coca, and this despite long periods of murderous repression in all three producing countries. ‘It has a secure market that guarantees a steady flow of income to the individual peasant households. This is coca's basic advantage.'xxiv In Bolivia, too, the collapse of the coffee price had a crippling effect on the farmers, and put paid to one element of the UN's Fund for Drug Abuse Control's AGRO YUNGAS programme that began in 1986. Described by Noam Lupu, it tells an exemplary security/insecurity-of-income story augmented by the arrogant, wishful thinking of UN officers bringing with them what Harry Truman had called ‘the benefits of our scientific advances.'xxv In the case of the Yungas area of Bolivia - the traditional coca growing and chewing, and coffee growing valley in La Paz province - the deal was to introduce four high-yield coffee plant varieties from Brazil and Colombia. These required a ‘technical package' of fertiliser and insecticides. Several years later only half the plants were in good condition and then a massive infestation of Broca disease destroyed 90 percent of coffee crops, including the local Creole variety. It's like a morality tale of arrogant ‘development' added to by wishful thinking. There was no alternative plan when the coffee price fell (60 percent in the period 1986-90).xxvi

Herbert Klein notes that what was special is that coca was overwhelmingly produced on small farms which were grouped into colonies or large peasant unions that were an effective voice for them.xxvii Adding insult to injury:

grown in combination with food crops it requires less investment and attention than other crops once it has been planted and will only require manual labor and no special skills [...] Also the production of cocaine is not a very elaborate or difficult process [...] the manufacturing process is not capital intensive, does not have large economies of scale, does not require large amounts of skilled labor, and uses production processes that are relatively easy to organize.xxviii

In short, there is no place for the inputs of corporate capital. No capitalist boasts about efficiency. No small farmer indebtedness. And, finally, as Klein puts it, ‘for the first time in modern Bolivian history, a primary export product was dominated by small peasant producers.'

Bio-Tool

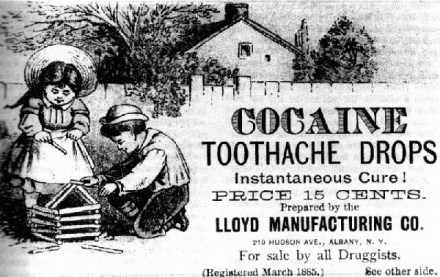

This crucial security of income for the coca farmer depends, naturally enough, on the steady demand for cocaine. The evidence that there is such a steady demand in the richer world is well known, and has sometimes prompted under-fire politicians of coca producing countries to tell the richer world that it's their problem. But ‘problem' is the most overused word in the political vocabulary, and it is rather the case that cocaine is a means of production or, more specifically, a component of the reproduction of certain kinds of labour in this richer world paid for by the person doing the labour. With the growth of the ‘white-collar' economy in the late 19th century, a new kind of intensity of labour was required and cocaine came into its own. Familiar names like Merck, Parke Davies, and Burrough Wellcome advertised it as both a performance and happy drug. Marek Kohn's comprehensive Cocaine Girls goes on to describe how a mixture of sexual, racial and military-discipline paranoias led, to its outlawing, but that in the meantime

the [drug using] individuals believed to be particularly at risk from the pressures of modern life were those with the most refined and sensitive nervous systems, those who worked by brain rather than hand; professional men, businessmen and ‘new women' [...] trying to make their own way in the world.xxix

In the present period there has been a revolution of ‘brain work' prompted especially by the IT revolution, with a whole section of the population engaged in different forms of the ‘digital economy'. This includes both the hitherto burgeoning financial sector and a whole range of the ‘creative economy'. It is no longer an ‘elite' drug, though one imagines that its relative purity is still class-income based, and there are horror stories. When free-basing was simplified to crack, the evidence of its effect on US city ghettos was well documented, though less so that it is a younger ghetto generation who have fought back against the drug and its effects in their neighbourhoods. In the streets of London it is truly depressing to see a ‘crack-head' early in the morning making speeches in the street without socks and in a puffa jacket whose zip has long broken.

Image: Ricky 'the Hitman' Hatton's coke binge

But this is a small section of the market. Even when it is a dance club drug - it's likely to be used by those in the IT/media/financial worlds given that there is so much sociological evidence of the blurring of work and not-work time. Cocaine is especially suited to work in these worlds because it can create indiscriminate but focused enthusiasm, by which I mean that the most banal piece of advertising or TV trailer can be felt as truly important. Unlike amphetamine whose sense of excitement tends to have a serially digressive effect, cocaine will allow you to stay single-mindedly on the task at hand for long hours.xxx It is also especially well suited to a world of overtime and short-term contracts. You are only as good as your last performance, while at the same time you may find your next job while having a line or two socially.

Yet how galling that a drug that is not just illegal but depends on ‘backward' farmers working communally (the ‘authentic' always preferred to synthetic cocaine) is such an important bio-tool for the ‘cutting-edge' economy. Its productive use cannot be admitted. There is, for example, not a single reference to it in Richard Florida's once-iconic book The Rise of the Creative Class. Similarly, there has been no reference made to its use in the ‘financial sector' in this period, when unrestrained, over-confident risk-taking caused an unprecedented financial crisis which we, the non-bankers of the world, are now paying for. It has not even been mentioned as a possible causative factor, though in the 1990s there were frequent newspaper articles on City of London cocaine use. In coded language they warned that its confidence-boosting quality might become dysfunctional when combined with a ‘masters of the universe' view of the world.

A post-crash report by Thomas Penny and Stephanie Baker also concentrates on city traders who are now ‘clean' or trying to be ‘clean' and makes reference to how

Professionals in the detox business say bankers have swamped them with calls since the financial crisis widened a year ago [...] some bankers are questioning whether the diminished rewards of the City are worth sacrificing their health for.xxxi

Given that the ‘sacrifice' of health refers to cocaine use, it's clear that it is functional to banking ‘labour' but only if the rewards are as astronomical as they have been, and are becoming again; more than enough to buy as much of the best flake as desired at any given time. There is no mention in Baker and Penny's article of any possible link to the financial crash, but rather a highlighting of that macho 14 and 16-hour working day which bankers have long used to justify their fabulous incomes.

Image: When cocaine was good for you

‘Fair Trade Cocaine', the Politics of Legalisation

It seems, then, all too fitting that $315 billion worth of illegal drug profits should have been used, as claimed by the UN's drug ‘czar', as ‘the only liquid capital' available to some banks on the brink of collapse in 2008. To get some idea of the significance of this amount, the IMF estimated that US and European banks losses between June 2007 and September 2009 amounted to $1 trillion. Señor Costa has no need to big-up this phenomenon, the very existence of the War on Drugs and its media support means his organisation will continue to be well-financed. Instead, what his revelation does is to demystify ‘money laundering'. There are plenty of accounts of the micro-business of laundering. Selective concern has been prompted by the other endless war, that against Terror. A typical report by AML-CFT might concentrate on the manoeuvring of a Chilean Exchange Bureau, while others would focus on notorious offshore locations. What Costa's assertion suggests is the significance of drug money as capital, i.e. of realised profit to the mainstream banking world and, as Ehrenreich says of the Mexican case, ‘The cartels are not revolutionary cells so much as organizations of global capital.'xxxii

Figures extrapolated by Feiling suggest that just one percent of the retail price of cocaine in the USA goes to the Colombian coca farmer; four percent to its processors and 20 percent to its smugglers.xxxiii Seventy-five percent therefore is realised in the rich world and, unless some of it can be claimed on corporate expenses, it will be a part of the reproduction of labour power borne by the worker-however privileged their job may be. In this way it can honestly be said that a large portion of the consumer price (that which is not spent by smugglers and dealers) will be realised as ‘laundered capital'. Other estimates reckon that people working in jungle labs are paid 75 cents a kilo. These disparities and the creation of usable capital on a large scale arise because of a self-interested, ideological and vindictive War on Drugs; drugs whose production have been made into an underpaid but relatively secure income for peasant farmers by the dynamics of global capitalism.

The mayhem and waste of resources caused by the War on Drugs demands however that we open a debate on the political economy of legalisation. This might start with a comparison with cocoa bean farmers in Ghana who get around seven percent of the price of a chocolate bar. The government of Ghana take a larger share in the form of tax. This is at the very least nominally accountable; some of the profits at least will go into public health and education facilities. As the position of such farmers in Côte d'Ivoire, shows there is no guarantee of such a redistribution, but at least decisions over how cocoa income is distributed are nominally open to public input.xxxiv

Image: Andreas Gursky, New York Mercantile Exchange, 2000

There are no guarantees that coca legalisation wouldn't simply mean the development of corporate cocaine oligopolies and high levels of tax in the consuming countries. It should also be remembered that although coca is also consumed by its producers, it is a cash crop. So far it has been grown alongside farmer-consumed food crops. Might this change, and the dangers associated with monoculture develop were it legalised? Might it also become a substitute for the redistribution of land in favour of the campesinos which is what really matters in Colombia. Bolivia, since the election of Evo Morales, the legalisation of coca, and the subsequent removal of the Drug Enforcement Administration from its territory, is a ‘test case'. I have heard worries from some Bolivian indigenous people that although cocaine is still illegal, some people have got more involved in it as a business and that this will destroy local communities. The hope is that the coalition which brought Morales to power is too experienced, and too mindful of the value of all its natural resources, for legalisation to turn Bolivia into a mono-crop exporter.

John Barker <harrier@easynet.co.uk> works as an indexer

iRajeev Sayal, ‘Drug money saved banks in global crisis, claims UN advisor', Observer, 13 October 2009.

iiBen Ehrenreich, ‘A Lucrative War', London Review of Books, 21 October, 2010, p.16.

iiiSee Drug Policy News, Drug Policy Education Group, Vol. 2 No. 1 Spring/Summer, 2001.

ivJohn Barker, ‘Intensities of Labour: from Amphetamine to Cocaine', Mute 2006, http://www.metamute.org/en/Intensities-of-Labour-f...

vThe shift of attitude during the Potosí silver boom in Bolivia - a boom that was an important kick-start to European capitalist dynamics - began with the Eccelsiastical Council in Lima condemning coca as the Devil Amulet in 1551. The Holy Inquisition was charged with enforcing the ban in 1567. But by 1573, silver mine production was so badly affected that King Philip of Spain abolished the prohibition. Just as in the present capitalist crisis, the cost of the reproduction of labour-power was pushed on to the labourers themselves: coca was taxed. Anthony Henman in ‘Mama Coca' estimated the coca market in 17th century Potosí had twice the turnover of food and clothing.

viFor example, US President Taft at the beginning of the 20th century, claimed: ‘The whole hemisphere will be ours in fact as, by the superiority of our race, it is already ours morally.' Sentiments later echoed by Theodore Roosevelt.

viiSilvia Rivera Cusicanqui, ‘An Indigenous Commodity and its Paradoxes - Coca Leaf in a Globalized World', Indigenous Affairs Journal 1-2, 2007, p.62.

viiiEven though heroin was scarce at the time, the relationship between this trend and the Vietnam War has been exhaustively described by Alfred W. McCoy.

ixJorge Hurtado Gumucio, ‘Cocaine the Legend', pp. 55-8. He goes on to describe how cocaine is mis-named as a narcotic, to give it a place in the ‘lazy native' discourse.

x The ‘Drug Czar' title was first coined by current US Vice-President, Joe Biden, in October 1982.

xiAcademics like Ransalaaer Lee, Eve Bertram and Jeffrey A. Miron; ex-law enforcement officers like Leigh Maddox and Jack Cole; politicians like ex-Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke, Gilberto Gil ex-Culture Minister of Brazil and now ex-President Vicente Fox.

xii This can be seen in several phenomena, such as the leasing and buying of large tracts of land in Africa by the capitalist corporations either on their own or with sovereign wealth funds; the concentration of capital in the biotechnology sector; the development of ‘terminator' seeds. There is a push by large capital to control all the basic necessities of life.

xiii Import quotas in favour of domestic production saw sugar imports in general fall by 80% between 1975 and the early '90s.

xiv Marceline White, et al., Women's Edge Coalition, ‘NAFTA and the FTAA: A Gender Analysis of Employment and Poverty Impacts in Agriculture', Trade Impact Review: Mexico Case Study, Washington DC, 2003 p iii.

xvBen Ehreenreich, op. cit., P18.

xvi Christoher Thompson, ‘Fears for stability in west Africa as cartels move in', The Guardian, 10 March 2009.

xvii Ibid.

xviiiFor descriptions of this dirty business, see publications of the Environmental Justice Network.

xix Héctor Mondragón, ‘Colombia: Agrarian Reform, Fake and Genuine', Landaction.org, 5 September 2005.

xx Colombia does have its own specific historical characteristics, though it is hard to know the weight of their significance. Francisco Thoumi points to the deligitimisation of the state which precedes the more general trend in this direction in other underdeveloped countries. While in ‘The Political Economy of the Drug Industry of Colombia' Menno Vellinga talks of a ‘production-speculation mentality with little investment in long-term equipment, a focus on commerce, quick turn-over and high short-term profit as conducive to the illegal drug industry.' Since this sounds rather like the UK it's hard to know how distinctive this makes Colombia.

xxiIn an instance described by Gary Marx, campesino-coffee bean selling entailed a five-hour mule journey to the point of sale, Chicago Tribune,19 April 2003.

xxii www.freelibrary.com/Grounds

xxiii Thomas Lines cites Oxfam on the loose arrangement in export horticulture for example, ‘Agreements are often verbal, so there is no written contract to break [...] Such informality gives buyers flexibility to delay payments, break programmes, or cancel orders, forcing suppliers to find last minute alternatives.' See Making Poverty, Zed Books, 2008, p.105.

xxivMenno Vellinga, The Political Economy of the Drug Industry, University of Florida Press, 2004, p.4.

xxv Development Policy Review, 22 (4), 2004, pp.405-21.

xxvi Lupu's scathing account talks of a ‘counterproductive conditionality on credits, a narrow vision and emphasis on short-term success, blind adherence to pure economic competition model, inadequate market appraisal of viable alternative crops, and paternalistic attitudes.' Dominic Streatfield also mentions how the one instance of an Agro Yungas success, a soya project, brought down the wrath of US soya farmers.

xxvii Herbert S. Klein, A Concise History of Bolivia, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 246-8.

xxviii Vellinga, op. cit., p.5

xxix Marek Kohn, Cocaine Girls, Lawrence and Wishart 1992 p.106

xxx There is a perverse mirroring here where crack users have spoken of the pleasure they get from ‘running about' and ‘being on a mission'. Desribed in Alex Harocopos et al., ‘On the Rocks: A Follow-Up Study of Crack Users in London', Criminal Policy Research Unit, South Bank University, 2003.

xxxiStephanie Baker and Thomas Penny, ‘Cocaine Survivors Losing London Bonus See End to Bubble's Binge', Bloomberg.com, 8 October 2009.

xxxii Ben Ehrenreich, op. cit., p.18.

xxxiiiTom Feiling, The Candy Machine: How Cocaine Took Over the World, Penguin 2009 p.177

xxxivFor details see Orla Ryan, Chocolate Nations: Living and Dying for Cocoa in West Africa, Zed Books 2011.

[For longer version go here: http://www.metamute.org/en/articles/from_coca_to_c...

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com