Citizens Banned?

Is a rabble run media becoming a possibility? And are artists in the vanguard or blocking the way? The AV media arts festival in the North-East of England last month suggested the ambivalence of artistic interventions into state and corporate broadcasting. Report by Anthony Iles and Josephine Berry Slater

This year’s AV festival, the third since its inception in 2003, had the subtitle ‘Broadcast’. Such a large and undifferentiated theme might seem to run the risk of courting meaninglessness, especially in the context of a media arts festival. In fact, AV’s engagement with radio and television in the age of Web 2.0 and digital switch-overs was unexpectedly productive.

Broadcast is a technique by which mass entertainment, amateur activity and artistic production, as well as disparate locations, can be united. Something which its deployment as a curatorial device at the AV festival, curated for the second time by Honor Harger, played with interestingly. There were amateur radio rallies, screenings in mainstream cinemas, a mobile radio-bus, and across Newcastle, Middlesborough and Sunderland, FM radio stations were set up. Diversity of format helped adulterate the space of art and blur the boundaries that still separate high from low culture. The festival’s programme seeped into the existing media landscape, inadvertently exposing local radio listeners to temporary stations of sound art, avant-garde music and the history of broadcast culture. The interrogation of broadcast technology’s conventions and exploration of its materiality imparted a spirit of enquiry and education to the events, opening up the black box of broadcasting.

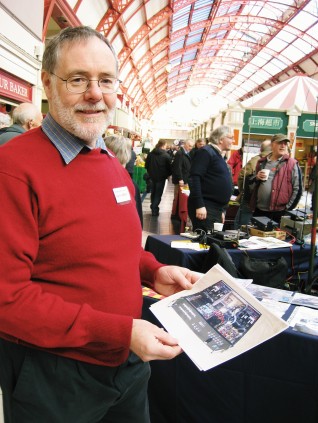

Artists and producers seemed to be simultaneously involved in critiquing, celebrating and mourning analogue TV broadcast on the eve of its national ‘switch off’ to be completed by 2012 (radio is, for the moment at least, a more complicated story, with no definitive switch-off planned). But the ways of registering broadcast culture and its (vanishing) potential were dizzyingly diverse. The Waygood Radio Rally at Newcastle’s Grainger Market was attended by amateur radio clubs from Northumbria, Tyneside and Tynemouth, and yielded a half-hour crash course in the basics of radio broadcasting and its global culture. Ironically, as one radio enthusiast explained, the old iron marketplace acted as a ‘Faraday Cage’ preventing all transmission and reception of radio waves. A frustrating experience for the wealth of enthusiasts who turned up keen to show off their skills and home-built kit, but an amusing one for the disengaged art flâneur. A laptop slideshow displayed pictures of ‘sport radio’ events in which single or double operator teams attempt to make radio contact with as many stations around the world as possible in 24 hours. There were also pictures of club members on solo missions to the far flung reaches of the earth, camping out on wind swept islands with disconsolate sheep, radio packs and vast antennae, attempting to transmit signals as far around the world as possible. In light of such touching commitment to the crackle and whistle of wireless, Northumbria Amateur Radio Club secretary David’s rather sanguine response to our questions about the rise of digital radio was disconcerting.

Image: David (G0EVV) at the Waygood Radio Rally, Grainger Market, Newcastle

David (call sign G0EVV), whose club members will not be affected by the advent of digital radio one way or another, did not know what the State has planned for FM and AM spectra freed up by the shift to digital. Conceding that digital audio radio (DAB) does not offer any significant technical improvements on analogue, he seemed unconcerned by the implications of DAB for smaller, commercially less successful stations. When asked about the activity of radio pirates, David was somewhat squeamish. Dissociating himself from pirate activity he declared that anyone in his club engaging in pirate broadcasting would be ejected forthwith for putting the club’s integrity and license into jeopardy.

The contrast with the relatively recent history of ham radio is striking. Up until 1989 severe restrictions on amateur licenses and access to broadcast technology forced radio hams in the former Eastern Bloc to broadcast secretly, running extreme risks in order to maintain contact with their peers. The cultural content of amateur transmissions tends to be minimal, with most messages consisting solely of the operator’s call sign, the date and the frequency; here the medium simply is the message. In ham culture, legal and technical limitations are continually present; contact is made through a low-intensity battle for space in the spectrum, channels are kept open. While some argue that radio’s combination of isolation and communicatin can constitute a space for critical reflection and the development of social relations beyond the constraints of the spectacle (see Marko Peljhan, http://linkme2.net/dy) in practice criticality appears to be largely absent from amateur radio. On the other hand, its practitioners’ tenacity and formalism has a structured reciprocity evidently absent from the actor/audience framework of art.

Moving from the encounter with David (G0EVV) to Chris Burden’s Four TV Commercials (1973/77) at the Broadcast Yourself exhibition in Newcastle’s Hatton Gallery produced a real sense of vertigo. For Burden to make these pieces he needed to form a non-profit organisation, since in this period American TV did not allow individuals to buy air-time. In his piece Chris Burden Promo (1976), Burden inserts his name at the end of a canonical sequence of artists from Michelangelo to Picasso. The names are simultaneously spoken and spelt out in brash yellow lettering on a blue background. In order to persuade the TV companies to let him screen the piece, he had to convince them that Chris Burden was an art company. Another Burden ad, Full Financial Disclosure (1977), made post-Watergate, consists of a breakdown of the artist’s accounts for the year 1976. Burden’s small net profit of $1,054 reveals how big an investment making the ads was for him, a form of economic self-mutilation that unites these works with his better known physical endurance pieces. For radio hams like David, gaining access to the fortress of broadcasting entails an acceptance of and even reverence toward its laws and codes of conduct because they maintain radio as a rational sphere premised on the formalist beauty of engineering. For Burden, in both of these works, it is about challenging the economic preconditions of broadcasting by producing something anomalously individualist within its own homogenous language and self-normalising continuum.

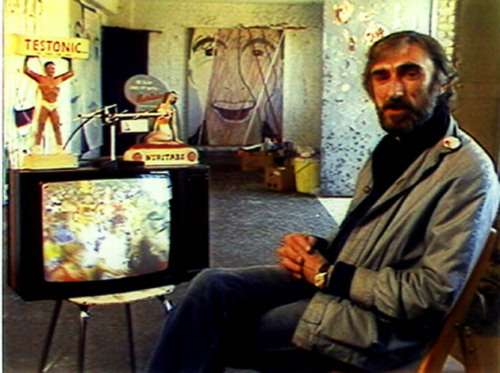

Burden’s détournement of blockbuster visuals and the political ruse of ‘transparency’ is all a far cry from Ian Breakwell’s self-consciously arty Continuous Diary made for Channel Four in 1982. The climate of tolerance produced by the State’s short-lived support for alternative programming is immediately apparent in the relative leisureliness of these episodes. Indeed, we later learned that Breakwell was allowed to specify not only their length, but the time of day they would be broadcast. In one episode, the artist is filmed on a bike cycling to work from London’s Smithfield Market to Wapping, dressed in a flat cap, green jacket and carrying a fishing bag. The eccentric figure of Breakwell cautiously cycling along his route, accompanied by his own voice-over narration, wavers between conceptualist farce and earnest Jackanory-style educational TV. As he cycles through the City financial district and past its landmarks, reportage of his daily journey cuts to news footage of a public celebration of the victory in the Falklands War. The pat poetry kicks in as he describes the assembled dignitaries and their ‘Grey, mean, stupid, faces’, or old soldiers and city workers ‘waving their little flags – enough to turn the stomach.’ ‘Either you die a hero,’ he concludes, ‘or Johnny comes home again.’ It all feels as distant and quaint as his flat cap. Surprisingly, the discipline imposed by American TV’s hostile commercial environment yielded a comparative terseness and medium specificity in Burden’s work that seems lacking in Breakwell’s over-extended and politically rather feeble pieces. Like a poet laureate licensed to break up the mundane code of national culture, Breakwell’s romanticist assault on televisual state propaganda ultimately reinforces its psychic regime by leaving the authority figure of the didact-presenter (artist) intact.

It is this domination of the media space by talking heads and the semantic regime they preside over that Sherrie Rabinowitz and Kit Galloway aimed to upset in their 1980 project Hole in Space. This piece connected the East and West coasts of America, with people outside New York’s Lincoln Centre and The Broadway department store in LA, speaking via a live satellite TV link up, and without any kind of censorship, pre-defined formatting or intervention. The artists insisted on having no prior publicity for the project, and allowed the situation to develop of its own accord over three evenings. During each two-hour transmission, live film of passers-by was projected on storefront windows in the corresponding cities. For Broadcast Yourself this footage has been edited down to an hour, synced up and projected onto two facing screens in the Hatton Gallery. The viewer stands in the middle and experiences the delirium of the growing crowds as they talk, sing, cheer and flirt with one another across thousands of miles, and without the inhibitions of embodied encounter or the dictats of broadcasting. The narrowcast and democratising dimensions of this project certainly preempts aspects of today’s social networking. But where Web 2.0 is defined by the solitary transmission and reception of pre-recorded or written material, Hole in Space coordinates mass participation into an unscripted exchange.

Image: Ian Breakwell, still from an episode of Ian Breakwell's Continuous Diary, 1984

Van Gogh TV’s Piazza Virtuale (1992), was a more sustained and distributed version of Hole in Space. An interactive TV experiment lasting 100 days, it was scheduled as part of Documenta IX in Kassel, Germany. The project used satellite network technology, with participants able to cut into a continuous TV programme through a series of Piazettas (blue ‘voxpop style’ public booths equipped with keyboards, slow-scan picture phones and ISDN lines) located across the city, or any touch-tone telephone. The keyboards and hand-sets functioned as typewriters, interactive orchestras and triggers for video games and painting programs. It was also possible to enter the Piazza via the internet, videophone or telefax and, beyond the Piazettas, there were live feeds from a host of other European cities. The screen was split into four, and the effect was a multimedia, dialogic, compound interface screened live on German cable TV, as well as the 3SAT TV network and the Olympus Satellite, with up to a million viewers. The edited down version shown at Broadcast Yourself conveyed a sense of a kind of ‘art glasnost’ with artists emerging from behind the iron curtain into the dazzling futurity of global interactive TV. It also produced some surreal solutions to live broadcast, with a Moscow art collective improvising a new ‘pocket art’ genre, by emptying out their pockets on air and encouraging others to do so.

As Karel Dudesek, former Van Gogh TV member, explained at a brunch at Newcastle’s Star and Shadow Cinema convened by Broadcast Yourself curators Sarah Cook and Kathy Rae Huffman, ‘the motivation was not just to get on TV but to change things’. The timing, he continued, was also fortuitous since the web had ‘just arrived’. ‘Nowadays,’ he lamented, ‘you’d need a whole floor of lawyers to produce mass live TV.’ Holding out for the importance of artists and ordinary people ‘hacking’ into mainstream TV and radio, he dismissed the impact of net based citizen journalism and artists’ broadcasts:

Radio and TV can change lives in a way that the net can’t ... TV is a group experience ... and people should be provoked to work with it.

If Broadcast Yourself rendered the golden age of artists’ TV interventions nostalgic through their presentation in a mock-up of a crummy ’70s English lounge (complete with sofa, electric fire, and wood-veneer panelled TV set), this feeling of ‘time regained’ was also applied to the recent past. Two late ’90s online curatorial projects, Bastard56kTV and TV swansong, related the advent of video streaming on the web (one of many new distribution strategies for artists’ work), and were displayed on Apple iMacs using 56k modems. This all brought back memories of the go-and-make-a-cup-of-tea speeds of early webcasting, and highlighted the commitment of these early pioneers to the ideal of many-to-many media casting in the face of extreme technical inconvenience.

Miranda July’s video collection from 1995, Big Miss Moviola (aka Joanie 4 Jackie), was a contemporary lo-fi experiment in the alternative distribution of artists’ video work. Described as a video chainletter, Big Miss Moviola started as an invitation from Miranda July to female video artists to make a film (no more than 20 minutes long), record it onto VHS tape and send it back to her. July then compiled the films onto tapes and redistributed them. In a sense, the tape makes tangible the bridge between mail art and Web 2.0 style social networking, whereby the pursuit of a like-minded audience for one’s work through alternative distribution methods actually produces a small well-connected milieu. In the case of July’s project, the tape’s inclusion in this show augments the cultural credentials of its contributors. The by-product of such networks then, is a cultural artefact with a rarity value readily sought by today’s cultural institutions.

One of the less familiar projects on display at the Hatton Gallery was Mumbai-based film-maker Shaina Anand’s open-circuit TV project KhirkeeYaan (Khirkee – window, Yaan – vehicle), which drew on relations and ways of being together unfamiliar to the Western media arts trajectory. Documentation from this project entailed episodes edited down from seven different installations of four open-circuit televisions, mics and cameras located in an area called Khirkee Extension in New Delhi. Through this basic network of cameras, a local, live and interactive TV programme was created. The episodes ranged from mob conversations between groups of young men featuring up to 20 people, to more sustained conversations between women of different castes from the privacy of their own homes. As with Hole in Space, the ability of narrowcast TV to connect geographically disparate spaces unleashed the thrill of tele-flirting – the virtual social encounter emboldening the participants. In her talk at the above mentioned brunch, however, Anand also underlined a more serious testing of social relations, as the strict codes of inter-caste and cross gender behaviour melted briefly away within this new, virtual space.

Although the documentation of Anand’s collaborative work parcelled the real-time, networked interactions into more manageble chunks, the original project was not conceived to fit the temporal framework of traditional broadcasting. This temporality has been described as the ‘monoform’ and the ‘universal clock’ by another important televisual dissident represented at AV, the maverick film-maker Peter Watkins. The monoform, he says,

is the internal language-form (editing, narrative structure, etc.) used by TV and the commercial cinema to present their messages. It is the densely packed and rapidly edited barrage of images and sounds, the ‘seamless’ yet fragmented modular structure which we all know so well [...] they are repetitive, predictable, and closed vis-à-vis their relationship to the audience.

The Universal Clock:

springs from the contemporary practice of rigidly formatting all TV programmes into standardised time slots (a total of 47 or 52 minutes for ‘longer’ films, and 26 minutes for shorter ones), in order to comply with a regulated amount of commercial advertising in each clock hour or half-hour.[1]

One of Watkins earliest films was on show at AV, The War Game (1965), his first and last BBC commission. Developing the then novel form of re-enacting fictionalised historical events which he had experimented with as an amateur film-maker, Watkins proceeded to make a film with a cast of non-actors about the consequences of a nuclear attack on the UK. Mimicking the starchy form of the public information films of the period, The War Game presents the public broadcasting voice-over as something entirely sinister, its objectivity complicit with the homicidal population management of the authorities and the public service workers who attempt to control the repercussions of a nuclear attack. This questioning of the BBC’s authority within the context of one of its commissions, the attempt to confront the public with the blunt facts of nuclear attack and ‘involve “ordinary people” in an extended study of their own history’ predictably resulted in the cabinet banning the film.[2]

Similarly to Watkins, film-maker Harun Farocki has gained a reputation for making films which strain the definitions of documentary or art house genres. His films have never gained adequate film distribution, relying instead on informal screenings in art spaces and museum film programmes for exposure. So, it is no great surprise that Farocki’s practice has shifted in recent years to accommodate itself to the defining terms of large-scale art installations.

Deep Play, installed at the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art in Sunderland, is a 12 screen study of the 2006 football World Cup final between France and Italy. Farocki assembles the various forms and interfaces through which the ‘beautiful game’ and its players are analysed, quantified and dissected as data. The installation explores how the spontaneity of a huge footballing event is subjected to manifold specular and analytical regimes in the act of its live broadcast and subsequent commodification. Two screens are reserved for a continuous shot of star players lasting half the game’s duration. One isolates French striker Thierry Henry from the games’ action, largely appearing in space on his own. In contrast to the constant dynamism of the televised match, this study captures the solitude of one player and his apparent frustration and boredom during the game. Here we are shown the atomised individual hero carrying out actions (a dance?) which seems absurd, more like the wandering lament of a prima donna removed from the supporting choreography of the team.

Deep Play continues Farocki’s study of technologies of vision and the militarisation of everyday life, transposed here from the obscure (grey media: training tapes, military and corporate propaganda) to the popular (televised sport). Another Farocki film screened during AV, Videogrammes of a Revolution (Farocki/Ujica, 1992), takes a more documentary approach to broadcast footage. In this case it is a study of the Romanian Revolution compiled through an editing together of intermittent public TV broadcasts and amateur footage over the course of three days. Here we see both the centrality of the TV station as a site of power and the vital role of national broadcasting in the projection and re-making of coherent power/authority. Protests throughout the three days shuttle between Nicolae Ceau?escu’s palace and the TV station as if unsure in which of the two institutions the power of the regime actually resided. Yet, as well as the machinations of turncoat generals and national hero-poets attempting to restore order behind the scenes, Farocki and Ujica direct our attention towards the apparently unrepresentable; the disturbances and undirected actions (in earshot but out of the camera’s view) which somehow tipped the balance of power, and remain mysteriously unattributable, unseen events.

A performance of John Cage’s Variations VII (1966) by :zoviet*france:, Atau Tanaka and Matt Wand was part of the Festival’s opening gala. Cage described the work as

a piece of music, indeterminate in form and detail, using as sound sources only those sounds which are in the air at the moment of performance, picked up via the communication bands, telephone lines, microphones together with, instead of musical instruments, a variety of household appliances and frequency generators...

The performance attempts to produce an aural picture of the metropolis, an aesthetic pursuit familiar from a long line of avant-garde writers, artists and music concrète musicians down to today’s sound cultures such as ambient and dubstep. In its AV iteration, the performers’ palette of sound sources included FM and ham radio, TV stations, feeds from scanners and mics in industrial spaces around the area, mobile phones and the internet. Unsurprisingly, the performance was marked by a tension between observing the rules of Cage’s original musical experiment, managing the noise of a plethora of channels, and the need to sculpt a recognisably authentic sonic experience for the audience.

In a sense this tension is built into the original work. Cage’s experimentalism revolves around the erosion of musicians’ agency in favour of his own semi-mystical conception of ‘chance’. It is not that Cage wasn’t making music, but rather he was trying to make music without musicians, and this is reflected in some of the documentation of the original performance. In their suits and horn-rimmed spectacles the performers look more like Harvard engineering professors. Indeed lab coats would not have been out of place. This is in stark contrast to the casual dress code of the latterday ‘technicians’ performing Cage’s piece at AV. Tanaka, Wand and :zoviet*france: operated a vast network of kit arranged over four large desks in the centre of the Baltic gallery. Where it seemed crucial for the original 1966 performance to be framed as ‘science’, this time around, with a good 30 years of computer music behind us, the shock of the technical array was not nearly so great. Without wishing to diminish the richness and quality of the sound collage produced, there seemed something not quite risky enough about the way Variations VII was staged and the ‘live’ performance itself.

Perhaps Variations’ careful and poetic collaging of the city’s ‘noise’ is an apt metaphor for the role of artists in mediating between the spectacle and its excluded. In order for the genteel audience of the Baltic to be exposed to the dirty, industrial sounds of North Shields Fish Quay or the hum of the city’s water treatment plants, a whole invisible web of professional liaisons and negotiation had to occur. These audio feeds, already bureaucratically and technically culled from Newcastle’s aural din, are then further refined by the performers, with no jarring noise ever allowed to sound beyond a comfortable degree. Artists act as the safe conduit through which the rabble can be admitted to the broadcast media space. Is it cynical to understand these kinds of state sponsored interventions as licensed dissent? The tasteful dose of noise that reassures us that we live in a (spectacularised) democracy? If inclusion is always a form of neutralisation, then under what conditions would it be possible to admit the mob into the national spectacle, and what would this rabble run media look like? If the emergence of ‘citizen journalism’ purportedly answers this question, enabling ‘anyone’ to publish their own material, the fact that encountering this material is often like searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack still leaves the problem of mass participation and collective reception unresolved. If artists’ broadcasts seem often to revolve around the desire for such a take-over of media from below, the radical levelling of power structures during events like the Romanian Revolution ironically seems to demand the artistic voice of the poet. A special voice was required to announce and make sensible, hence safe, the extraordinary events that were unfolding. But no matter how problematic the artist’s role as mediator, in the absence of any radical democratic access to the TV power-tower, their marginalisation within the current proliferation of media channels is symptomatic of the triumph of the state-commercial media apparatus, albeit as polyform not monoform. In the words of Dudesek, ‘Today we are living in one global advertisement for “shiny lips stay young forever”.’ Events like AV, apart from bringing together a wealth of thought provoking material, are certainly good at reminding us that lip gloss is no cure for psychic entrainment.

Image: Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica, still from Videogrammes of a Revolution, 1992

Josephine Slater is Editor of Mute

Anthony Iles is Assistant Editor of MuteInfo

The AV Festival 08 took place in various venues across Newcastle, Gateshead, Middlesborough and Sunderland, 28 February – 8 March, 2008, http://www.avfest.co.uk/

Broadcast Yourself was at the Hatton Gallery, Newcastle, 28 February - 5 April, and will be on show at Cornerhouse, Manchester, 13 June - 10 August, http://www.broadcastyourself.net/Footnotes

[1] Quotes from Peter Watkins 'The role of the American MAVM, Hollywood and the Monoform', http://www.mnsi.net/~pwatkins/hollywood.htm

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com