Brutalist Soap

What lies beyond the failed utopias of the modernist welfare state and the free market? Gail Pickering's recent film/performance, despite its strictly internal focus on life inside a Brutalist housing estate, opens up scope for speculation. Review by Kate Rich

Brutalist Premolition is a new film work by Gail Pickering. Pursuing her interests in performative fiction and social ritual, the film shows actors – well known faces from East Enders – being auditioned to play actual East Enders on a London housing estate. The work was commissioned by Media Art Bath and screened as part of a one-night live performance at the Arnolfini in Bristol.

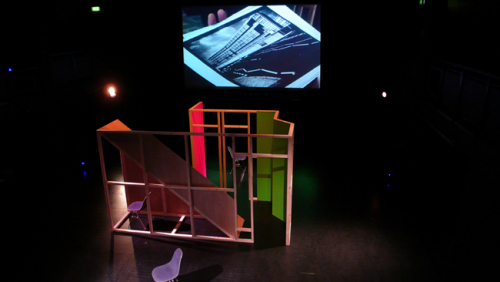

The performance took place in the dark surrounds of Arnolfini's Dark Studio, blacked out except for a starkly lit set in the centre of the room: a wood frame structure sketching out the interior of an apartment, the steep incline of an inside staircase, and the two actors, Raji James and Babita Pohoomull, sitting brooding on chairs. The set was not optimally viewed from any particular angle, so the audience prowled around it for a while trying to position itself.

Image: Gail Pickering, Brutalist Premolition installation view, 2008 (courtesy the artist)

After a long wait the film played once, then the actors in the room broke into monologue, word for word the same scripts they perform in the film, then the film ran again. The cycle repeated. The doppelgänger effect – the TV actors from the film re-acting family minidramas of soap-like emotion in the confined space/time of the Arnolfini theatre – was a bit of a mindfuck, possibly evoking the sensation of growing up in the Robin Hood Gardens Estate.

Robin Hood Gardens is an estate in Poplar, Tower Hamlets. Designed by Alison and Peter Smithson, it is cited as a key example of post-war New Brutalist architecture, intended as a utopian form of large scale social housing. Built in 1972, just one year after the term 'London Docklands' was used for the first time in a government report on redevelopment, the crumbling estate whose vistas once stretched unimpeded to the old West India Docks now finds itself only minutes from the 14 million square foot business and financial development of Canary Wharf. Robin Hood Gardens recently loomed back into the public eye through a campaign to secure it Grade II listing with English Heritage, in order to breathe new funds into its failing 20th century structure of precast concrete slabs, twisting staircases and 'skywalks', and save it from proposed destruction.

Pickering's film is shot entirely inside one of the estate's flats. It opens with a montage which echoes the striking, repetitive and angular geometries Brutalism is credited with: glimpses of residents holding photographs – black and white momentos – possibly from archives – of the estate being built, then family photos and extended family photos such as one of Princess Diana. The actors arrive at the flat, a Bengali family home, and begin reprising scenes from their own back-repertories of TV and stage performance as the family watch or feed them lines from a script. A casting session for another film not made; disconnected slices of family life, death and struggle, without context or resolution. Then the film would end and the performance in the theatre start up again.

While experiencing the performance – with the live actors, looping through the same scripts they perform in the film as relentlessly as an eco-washing machine fulfilling its cycle – often risked flaring into semi-unbearable oppressiveness, the film's compact coding flowered through repeat viewings, as fleeting images emerged as if from developing fluid to settle into tangible objects.

Brutalist architecture is described as space to do things in. Its design qualities, use of space and proportion were conceived by its makers as an audacious experiment in improving social housing. The film opens to the asymmetric sounds of a youth bouncing a football off the walls of his single cell like bedroom, approximating a caged parrot who has figured out bizarre recreational moves to do in its box, warding off the madness of enclosure. Like an Englishman's castle, the homes in the Robin Hood Estate were not designed for looking out of. In the flat, net curtains cover the few windows favoured by Brutalist buildings (often including windows designed not to open); only the always on TV peers outside the battlements to some fantastical verdant world beyond, full of Bollywood dancers.

Image: Gail Pickering, Brutalist Premolition, video still, 2008

Unnervingly in this case the view is also reversed as the East Enders actors arrive at the flat and hang out with the inhabitants – a subversive kind of narrative violence, as TV enters the home – plus, more shocking, emerge from the film to air their outsized canned emotions inches from us in the Arnolfini. The limits of the various screens interlope with each other, disconcertingly.

The film also stars household décor: the social lives of ornaments and fixtures. The flat's stark matt concrete walls loom over every scene, but its inhabitants resist Brutalism's dream of unadorned functionalism, nurturing a carefully placed miniature indoor palm, vase, hanging chimes and flock of goldfish swimming in the widescreen TV screensaver. A wrought metal butterfly lands on the plastic ivy. The family are positioned formally in armchairs, thick walls around them, although muffled sounds of children playing outside filter through. The theme of interiority, containment, continues in shots in the lift and staircases. At the Arnolfini we experienced a kind of opposing agoraphobia, by the half hour mark the audience had slunk back against the theatre's supporting walls. As the film/performance/film continued to loop without clear exit point, panicked boredom set in and I found myself taking a Brutalist look around at the bare functionality of the Dark Studio, its exposed lighting technicians, trusses, exit signs and two Media Art Bath staff videoing the whole TV-film-theatre gateaux. By the time it wound up after five or six full reps, I too was bouncing off the walls, although a musician friend whose main thing is sampling actually enjoyed it. We rinsed ourselves out in to the Arnolfini foyer where champagne was being served.

Not recognising familiar East Enders actors probably didn't help the experience of the work, although from asking around afterwards it seemed that this problem was common, suggesting perhaps a mutual exclusion between film's subject territory and the audience for it as art. Can meaning survive over this kind of chasm? More noticeably untranslated was the specificity of time, place and politics around Robin Hood Gardens – basic data which does not really make it out of the project's information pack. But while it is possible to suspect the project of gaining currency via proximity to honeytrap issues such as urban regeneration, Pickering's approach to her work, which she has described as 'oblique', is a lot more complex, showing a considered history of ambiguity and non-compliance around the fundaments of art and social engagement.

The film's mixed cast of residents playing themselves alongside incongruously professional actors echoes the collage of sources in Pickering's previous works – a gallery installation with loitering bodybuilder (PraDAL, 2004); an actor in another gallery executing a set of movements evocative of '60s and '70s guerillas (Zulu [Speaking in Radical Tongues], 2005-2008); a film starring porn actors being transported around rural France in geometric costumes, laughing at the incongruity of task they are scripted to perform (Hungary! And Other Economics, 2006). Pickering's experimental aesthetics of performance and collaboration openly leave the politics of participation unresolved.

Image: Gail Pickering, Brutalist Premolition, video still, 2008

With the film's charged interiority there are a lot of other things we don't see, for example any exterior images of Robin Hood Gardens (other than the glimpsed archival photos), or its multi-million pound views of Canary Wharf's glittering towers, if that's the kind of thing you appreciate in a home. Although further thoughts on the intractability of Brutalist and other council housing as raw material for developers, in particular Robin Hood Gardens' unsuitability for conversion to dormitory stock for finance workers, subside when at the time of writing the plummeting Citigroup axes midair another 1,250 jobs at its Canary Wharf HQ, under the slogan 'Getting Fit – Fast!'. It is even possible to imagine a future where London's second greatest banking citadel is itself offered the salvation of demolition.

Robin Hood Gardens failed to get its Grade II listing in July 2008, despite a campaign led by architectural industry magazine Building Design which claimed it as an important modern building. UK Culture Minister Margaret Hodge ruled the estate 'not fit for purpose', after a report from English Heritage which advised amongst other things that 'it does not compare successfully with other 20th century estates listed at Grade II such as the Barbican and Brunswick Centre'. The Brunswick Centre in central London, another piece of utopian social housing in a neighbourhood of creeping affluence, successfully renamed itself 'The Brunswick' – as in 'Many of the best names in British retail and fashion favourites are now located at The Brunswick: French Connection, Coast, Oasis, Joy, New Look [and] Hobbes and Chocolat Chocolat a choc-a-holic paradise' – after its 2006 renovation, a makeover previously repeatedly blocked by residents' committees.

That the Robin Hood Estate escapes instrumentalisation, rehabilitation and resurrection might not be a bad thing though, for the 80 percent of residents who would prefer to be rehoused, according to some surveys. Although reports of rats, leaks and overcrowded families can alternately be explained by long-term council disinvestment in the building, not to mention social housing in general. Residents who choose to stay in the regeneration area will have to move to a 'social landlord' who will run the English Partnerships' Blackwall Reach scheme on the site.

Viewed from inside the Arnolfini, itself a Grade II listed, 19th century tea warehouse (internally a 1970s concrete framed office block, but refurbished in 2005 with the help of an Arts Council / National Lottery grant) it is hard to pick which of the four horsemen of Culture, Regeneration, Global Finance and Social Benefit should decide Robin Hood's fate. The prolific developer Urban Splash ('in the beginning there were factories. And they weren't working any more. But we thought they were beautiful') currently redeveloping the listed Brutalist Park Hill Estate in Sheffield, had voiced an interest in taking over RHG. Although breaking news from Building Design (November 2008) that some 60 of Urban Spash's total 280 staff have just been made redundant, might scupper this option. Then again you never know, the 20th Century Society – campaigning for the preservation of the best buildings of our period – was successful in its appeal for a legal review of the non-listing, and the campaign to save the building continues.

Kate Rich <kate AT bureauit.org> is an artist and trader living in Bristol UK, and a member of the Bureau of Inverse Technology (BIT).

Info

Gail Pickering's Brutalist Premolition was commissioned by Media Art Bath and performed at the Arnolfini, Bristol, http://www.arnolfini.org.uk/whatson/events/details/184

http://www.bdonline.co.uk/story.asp?sectioncode=725&storycode=3127764&c=1

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com