Bolivia's War of Wars

Sebastian Hacher discusses the latest phase of the War on Drugs in Bolivia, and explains its connections to the broader political strategies being deployed against the country’s people. Strategies for resistance such as road blocks and striking have produced potent results, portrayed by the liberal regime as a conspiratorial coup

In sad or melancholy moments, the coca leaf lulls away pain and gives to the eater joy and well-being.

If someone wishes to divine their destiny, a handful of leaves thrown to the wind will disclose the secrets of their future.

But when the white man tries to do the same, and dares to use these leaves as you do, the opposite will happen [...]

Its juice, that for you is strength and life, for these masters becomes a repugnant and perverse vice...

– Local legend, La Paz, Bolivia

From pre-colonial times Bolivia has been linked to the culture and economics of the coca leaf, from the tropical parts of Bolivia, to the Yungas of La Paz, to the Chapare near Cochabamba. For Bolivia’s original inhabitants, the plant was and is a food medicine and a religious sacrament. In addition, it is the only secure source of income. From 1985, when 32,000 miners, 18,000 manufacturing workers and 2,000 from the banking sector were dismissed, the country’s rural areas began to receive thousands of people, all looking to the production of this prohibited leaf to support themselves. At the moment 100,000 people are considered to be living directly from its production, a figure which is rising rather than falling.[1]

What then of the Bolivian government and the US Embassy, who declared a zero tolerance policy concerning the coca leaf in 2000, with law 1008, ‘The Battle Against Drug Trafficking’ and ‘Plan Dignity’?[2] For these authorities, coca is a demon to be eradicated – as if the leaf itself were the principle reason for the production, traffic and consumption of cocaine. What has not registered with many is that it is in the United States that 90 percent of all cocaine is consumed, at the rate of 1.5 tons a day[3], and that the US Drug Enforcement Administration and the Central Intelligence Agency – whose Bolivian offices are some of the largest in Latin America – are proven accomplices in drug trafficking. Despite all of this, for the ‘The Embassy’[4] the thousands of farmers fighting to survive and maintain their traditions are the enemy.

In pursuing their objectives, the two authorities have resorted without scruple to the slaughter of farmers. During the last three years, thousands of soldiers have been mobilised into rural areas, mainly to the Chapare. Here, tortures and murders are commonplace in the process of compulsory eradication of coca crops. As one farmer says, ‘sometimes they come in the night and remove our brothers from the bed. “Get moving!” they say, and with blows and with guns they force them to cut down their plants. The soldiers use the farmers’ tools, they take everything, and sometimes they burn down their homes. There are brothers from whom they stole everything. They hit one and his guaguas (babies) and then took his animals and the crops that were not coca.’[5]

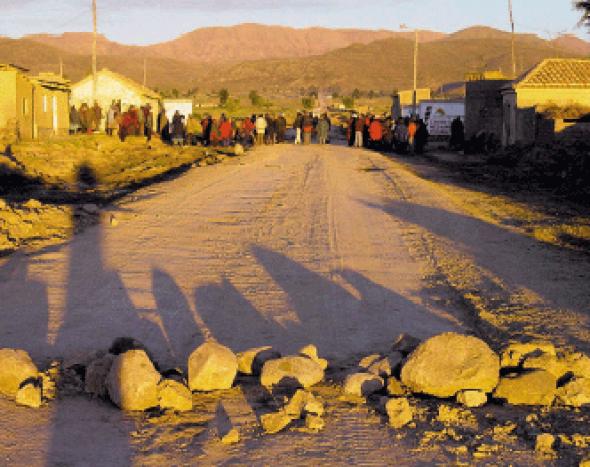

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

The farmers have not remained silent about such treatment. In the Chapare area alone, 30,000 families have organised into six federated unions. Although these organisations have existed for 18 years, they have gained a new prominence since the millenium. As well as linking and organising the social and economic lives of the farmers, they now also help them defend themselves against the depredations of the authorities. Demanding an end to the imposed eradication of the coca leaf, these unions are standing up against state sponsored repression through their ‘self-defence committees’.

UNITED STATES POLICY: ‘ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT’

The ‘alternative development’ policy established by the United States, which supports the planting of crops like the banana or the palm trees, is in fact nothing more than a swindle. Firstly, these are unprofitable crops which bring new pest problems. According to one farmer in the region, ‘now I have bananas everywhere. But they brought with them a new tiny insect that we cannot control. On top of that we were promised that we would be paid 3 Bolivian pesos ($0.33 US) per kilo. We ended up getting half a peso ($0.05 US) a kilo.’

Secondly, the plans financed by Washington are a source of endemic corruption. In the Chapare region, 60 percent of the funds destined to develop alternative programs are spent on ‘administrative expenses’, and in other areas they have had no influence in the replacement of coca leaf crops at all.[6] Indeed, among farmers the policy of the United States is seen as less a ‘Battle Against Drug Trafficking’ than an attempt to control the natural resources and the labour force of the country. Bolivia has the second largest reserves of natural gas in the Southern Cone, with 57 trillion cubic feet and potential reserves of up to 100 trillion cubic feet. The Bolivian labour force, moreover, is not only cheap but highly skilled, with 40 percent of workers concentrated in the artisan and small manufacturing sector. There are some who see the county as an ideal resource waiting to be developed. Through the mechanisms of the War on Drugs and the FTAA (see article on p.42), they hope to turn it into a zone as exploited and exploitable as northern Mexico or the sweatshops of northern Asia.[7]

In the last few years the United States has begun to intervene politically in the daily life of Bolivia. Four million dollars a year of North American money is destined for military aid to fight farmers. Another 91 million is designated for the battle against drug trafficking, some of which will go into the construction of an ‘anti-insurgency base’ in the region of Chapare, a place where guerrilla movements have historically been neither successful nor popular, and where today there are no real attempts to build armed resistance. (Directing this operation is Mr Greenlee, ex-head of the CIA’s Bolivian office, and the brand new ambassador for the Bush administration.) Pressure from Washington has tipped the balance in recent elections towards Sanchez de Losada, the latest ‘serious’ representative of neo-liberalism in the region, and away from Evo Morales, a candidate who came from the peasant movements and who had been set to win. It was clear during these 2002 elections that the US saw in Bolivia, and sought to prevent, the possibility of a rerun of Venezuela’s recent history.

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

RESISTING THE WAR

The blockading of roads and highways as a form of protest has arrived in Latin America for good. Inaugurated in 1996 by the Argentinian unemployed, it is a method that has as its objective the restraint of the circulation of goods and people. Its goal is to force the authorities to take into account movements that are being displaced from or are outside the circuit of production. This method, taken up by more radical movements, has extended to Guatemala, Brazil and Colombia as well as Bolivia, where blockades beginning on the 13 January 2003 lasted for two weeks, resulting in 14 dead, 200 injured and more than 1,000 detained. According to a farmer in the locality of Chimore named Jose, ‘Sometimes when we were in the mountains travelling to a blockade they would grab us and they tortured us. They caught me early one morning. That I survived was only because we could be heard. The soldiers’ fear made them negligent, and I was able to escape.’

In this latest round of blockades, confrontations with the authorities have been marked by severe violence. Police and army forces have used military grade ammunition and tanks to face down farmers who defend themselves with only stones and slings.

A NEW AGENDA

Along with these new mobilisations, Bolivian farmers have began to frame their own political agenda, raising the idea of ‘zero drugs’ as opposed to ‘zero coca.’ They have proposed a plan for the industrialisation of coca leaf production as a food and medicine.

Of the thousands of substances that the coca leaf contain, the farmers say, only one is harmful: the chloride of cocaine. They propose to set out a way of working that avoids zones supplying the drug trafficking trade. But they are also beginning to take the needs of an entire impoverished nation into their hands, focusing on the export of natural gas to Chile, the formulation of the FTAA and sovereignty, and issues of land ownership and territory.

The government of Sanchez de Losada, which tries hard to carry out the orders it receives from Washington, has continued to fight Bolivia’s farmers tooth and nail. But on 26 January 2003, after the violent confrontations of the blockades, the government was forced to take up the dialogue proposed by the farmers’ unions. Shortly before this dialogue began, the farmers united with manufacturing unions, university students and intellectuals under the name ‘The Major State of the People’ to organise a national mobilisation in all sectors of labour. On the table are seven key issues for the Bolivian people: the coca leaf, human rights, the Earth, land and its ownership, natural gas, the FTAA, the national budget, and the US plan for ‘alternative development’.

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

>> A meeting of all the coca unions in Chapere, Bolivia, at the end of January (27-30). By Sebastian Hacher

THE WAR IN LA PAZ

Encouraged by this outbreak of dialogue, The Major State of the People suspended the pressure tactics it had been using. Unfortunately, the government took advantage of this return to relative normality to declare that ‘the dialogue was simply that, a dialogue... nothing is going to come out of it’.[8] Sanchez de Losada presented the end of the blockades as a ‘triumph for the principle of authority’, and immediately announced, on 10 February, a cut in the monthly wages of urban workers by between four and 12 percent. The cities did not wait long before exploding, and two days after the announcements, a police rebellion checked government authority in the city of La Paz, which had decided to take the army into the streets. In the course of two days, during massive spontaneous popular mobilisations, confrontations between the police and military, burning of official buildings and strikes by the Central Bolivian Workers Union, the government was forced to retract these cuts. The fallout was 35 people dead and 200 injured, many of them by the bullets of army gunmen. Among the injured were two nurses who, dressed in their white uniforms, had tried to rescue the wounded.

The government denounced this ‘conspiratorial coup’: demonstrators were called vandals, army snipers presented as opposition infiltrators, and the farmers’ deputies who had helped with the mobilisation blamed for everything. All of this has failed to obscure what is in truth the breakdown of a state totally subordinated to foreign interests, and perhaps the beginning of the construction of a new unity between the disenfranchised peole of both country and city. If we take into account the Bolivian tradition of uprisings and revolt, perhaps we can see hope in the legend of the coca leaf, which may sooner rather than later fulfill its prophecy.

[1] Data from the CEDIB – Annual of Coca 1992[2] The ‘Law of Dignity’ voted in during the government of Bazer, proposing to eradicate coca by 2002[3] Information from the US State Department annual update. 60 tons of cocaine was produced in Bolivia during 2001, much less than in Colombia and Peru[4] ‘The Embassy’ is the popular name for the US Embassy. It has and active role intervening in the Bolivia’s political life and mass media[5] All the testimonies of farmers were gathered durring the last weeks of January 2003, throughout the Chapare, and in the villages of Chimore, Shinaota and Puente Roto[6] Surprisingly, a report by the the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Oficina para Asuntos Internacionales AntinarcÛticos and the EjecuciÛn de la Ley del Departamento de Estado (who finance the plans for ‘alternative development’) recognises that in the region of White Carani and Palos, the subsidies were used for the eradication of just 40 hectares of coca leaf[7] The average wage of a Bolivian worker is 100 dollars a month. Data from the National Institute of Statistics 2002 [8] Declarations from vice-president Carlos Mesa to all of the mass media outlets in the country

Sebastian Hacher <sebastian AT linefeed.org> is an Argentinean who has been working with farmers and urban workers in Bolivia for two months. He recently spent months living with workers in an occupied factory. Sebastian currently writes on the situation in South America and works with Indymedia helping local unemployed unions (piqueteros)

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com