Blue Skies Over Bluewater

The Thames Gateway looks set to be the latest in a long line of ‘great’ British planning triumphs including Milton Keynes and London's Docklands. But is it possible it could be worse than either of these?

Michael Edwards is a professor of planning at the Bartlett in London. Here he analyses the likely outcome of the Thames Gateway project, and offers his own alternative vision for redevelopment

The Thames Gateway project poses daunting choices for those with the power to decide on the future development of South East England. Government and the Mayor of London both agree that most of the region’s growth should be concentrated in the Thames estuary. They share the assumption that London has to expand East, not West, and that the supposed rationality of capitalist growth is the only telos in (or out of) town.

But is this even a good project on its own profit-driven terms? A toxic mix of de-regulation, state subservience to corporate interests, political cowardice and collective amnesia about how to do urbanisation, all the signs are that Thames Gateway will be UK regeneration plc’s biggest debacle so far.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The new city could be a laboratory for innovation in ways of living, ways of building and ecological relationships. The reality may be somewhere in between. In this article I will sketch my worst and best case scenarios. First, a bit of background.

Capital Problems

London is a problem region and its eastern part has special problems. London sucks in wealth created around the world, staffs its hospitals and services with people trained in poorer countries and drains the skilled people from much of the UK.[1] Meanwhile its internal unemployed ‘surplus population’ (of many ethnic groups including poor whites) remain largely overlooked within the city, squeezed between low wages or benefits and high living costs.

One result of this sucking in of resources and of highly educated people is economic growth, hailed as ‘wealth creation’. The growth package comes with expanding employment and population and even faster price increases, especially for housing. The government and the Mayor of London just welcome all this expansion and insist that London somehow has to go on growing. We are told that any restriction of this growth could kill the goose that lays the golden egg: investors would go elsewhere.

Expansion along the radial corridors to north, south and west could be a good solution but there is a taboo on that because of the strength of resistance from the property-owning classes who defend themselves so vigorously in the green belt round London. The county of Buckinghamshire fought off the threat of urbanisation in the 1960s by telling the government that, in return for preserving the leafy Chiltern Hills, they could have a free hand around the stinking brick kilns (and Labour voters) of Bletchley. That’s how we got Milton Keynes. Now we get the Thames Gateway for much the same reasons: the people east of London could do with more jobs and the NIMBY forces simply are less powerful out that way.

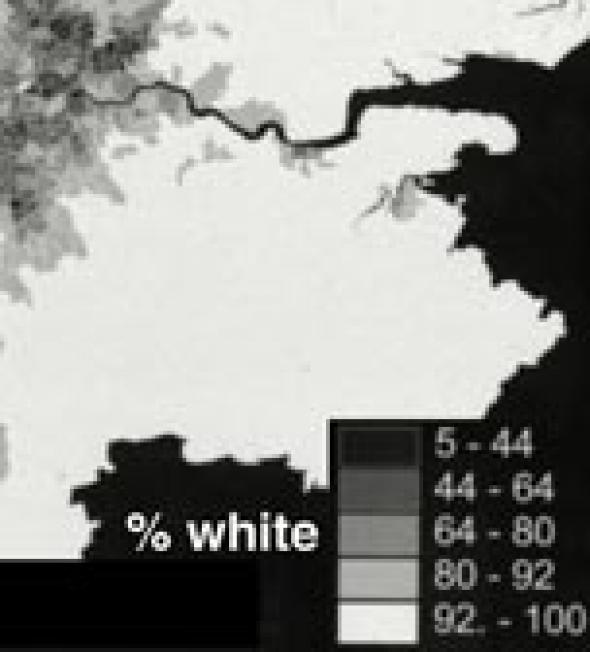

London has a long history of problems to the east. This is where the most polluting industries went, outside the environmental and safety controls of the old London County Council – east of the River Lea on the north bank and east of Greenwich on the south bank. It was the backyard of London with power generation, garbage disposal as landfill in the Mucking marshes, car-breaking and the rest. It also had the Ford plant at Dagenham, oil refineries, cement, armaments, paper and cardboard manufacture among its main industries. With the destruction of manufacturing in the UK since the Thatcher period this part of England suffered catastrophic job losses which produced an abandoned working class and a fertile ground for racism. A bit away from the rivers, the east has long been a dormitory area to which east Londoners have moved when they could afford to do so, and these movements have been disproportionately of white people. London itself may (and should – see Mute Vol2 #2) celebrate its diversity but at the edges of Greater London and especially in the counties beyond its boundaries the social landscape is very white.

Employment growth has been strongest in central and western London. That trend follows the market, reinforced by decisions to expand Heathrow and by Ken Livingstone’s determination to foster finance and business services in the centre. London cannot house its growing labour force so it has to suck more commuters in from outside – especially from the dormitory areas of the east which are the least self-contained parts of southern England. From the point of view of employers in the City, West End and Docklands, their future growth depends on even more commuting from Kent and Essex. But the trains which bring them in are jam packed and central London employers (and property owners) are pushing for investment to increase their commuter capacity. Services from Kent will start running on the Channel Tunnel Rail Link tracks in 2007 and there is strong pressure for that to be followed by ‘Crossrail’, although the wider economic and social justifications for it are weak.

Ken Livingstone now has some influence over the privatised surburban railway system of the region, but Transport for London (TfL) is struggling to find ways to enlarge the system’s capacity to get the new workers in to the centre, even with massive state investment and maintaining a 2006 level of overcrowding on the trains. And it is very wasteful: every packed train coming in to the centre runs back nearly empty for the next load of Kent and Essex commuters. This is less of a problem going out of London in other directions to places such as Milton Keynes, Watford, Reading and Gatwick. There are more jobs out there and thus more reverse commuting. Major population growth in the east thus has disadvantages from an energy point of view.

Another problematic feature of this eastern region is ecological. The modern parish of Mucking, for example, has been described as one of the most derelict on the north shore of the Thames (Astor, 1979): the higher land worked for sand and gravel, and the marshes along the river covered by London rubbish (Middleton, 1994). The Thames Gateway needs a major investment to clean-up polluted land; the huge landfilled marshes at Mucking may be damaged beyond repair and many of the areas proposed for urban development are vulnerable to flooding – either now or as a quite likely result of global warming in the future.

Worst case scenario...

If the Thames Gateway project goes ahead with some of these major challenges unresolved, pessimistic foresight suggests the following:

The cost of making it happen at all – building transport and social infrastructure as well as subsidies for clean-up of land – is an endless drain on state investment. The 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games helps a bit in this respect because the sheer imperative of being ready on time for the Games permits normal decision-making and consultation to be compressed and ensures that budgets will be found to do roadworks and other bits of infrastructure in the national interest. Even that is not enough, however, and much of the infrastructure lags years behind the need.

The growth of the region’s population and income in turn boosts growth of property values in the south of England, leaving the west and north of Britain to struggle. Government statements about regional policy – already very feeble – become even less convincing as state expenditure on the Olympics, and then on urban infrastructure and housing, further overheats the South East. As house prices (and rents) are driven up in this way, low- and middle-income people suffer worsening housing conditions, more overcrowding and dependence on housing benefits.

Mass private housebuilding firms are cajoled into building thousands of houses a year but each development serves just a single market segment and income group. The higher ground and fine landscapes get the ‘executive’ homes; the marshes and degraded areas get denser blocks of apartments, euphemistically called ‘starter homes’, and ‘affordable’ housing. The housebuilding industry remains profitable, though this is largely because selling prices are growing year after year: housing in Britain remains poor value for money in European terms and more than half of what you pay for a dwelling is payment for the scarcity of land, not for the dwelling. A steady influx of workers from eastern Europe cushions the construction sector from the need to modernise itself.

Apart from jobs in construction, the economy of the Thames Gateway grows only slowly, so its population remains dependent on long-distance commuting, mainly to Central London. There are more trains running, but they still have cattle truck conditions. Stratford, Ebbsfleet (a.k.a. Bluewater) and Ashford have high speed, and expensive, services to St. Pancras but many areas are only served, at best, by ludicrous extensions of the Docklands Light Railway – in truth just a tram – with dozens of stops between home and work. Anyone who has sat for an hour on the Athens tramway to the southern suburbs (built for the Olympics) will know what I mean.

Some prestige architecture will decorate this messy picture, with flagship projects here and there. There are wonderful designs by Zaha Hadid, AHMM, Bernard Tschumi and Colin Fournier... But these are fragments lost in a sea of mediocrity, dominated by routine architectural firms commissioned by big development companies and the ‘Registered Social Landlords’ who have already shown that they often do no better.

A lot of money is made even in a low-grade development of Thames Gateway. Pressure of demand for space in London is so strong that everything sells sooner or later and property values grow through the agglomeration of activity and the new infrastructure. But the profits from this are all private because successive governments have not had the nerve to hold any long-term land ownerships or equity shares. Governments insist on getting ‘planning gain’ contributions out of private developers for social housing, infrastructure and so on. But they do it in year one, just when the developers can least afford to pay and long before the trees have grown and the serious land values built up. In this worst case scenario it is always the state and public bodies that come to the rescue, firefighting on service provision, patching infrastructure. There may be some exemplary water-management and local-energy schemes – these are being promoted hard just now by the Deputy Mayor and likely to figure strongly in the next London Plan. But these schemes need continuing management to work and if all the profits have been given away – either to initial developers or to individual owner-occupiers – these costs will be hard to cover.

The British appear to have forgotten the positive aspects of the 20th century new towns programme. One of the great strengths of that programme was that it was financially sustainable in the medium and long term. Large-scale urban development involves heavy initial costs while the benefits are reflected only very slowly in rents and property values as each city matures. In the new towns of Britain the government agencies which built them retained ownership of a lot of the land and buildings and could thus recoup the investment and pay off the loans. This is just what we are failing to do in the Thames Gateway: as with Mrs Thatcher’s Docklands project in the ‘80s, all the valuable assets end up in private hands and there is no flow of public or collective funds to pay for maintenance or services or repay the debts incurred in the initial infrastructure. [Editor’s note: An early Thames Gateway plan was drafted by Michael Heseltine during John Major’s government.]

And the best case...

Instead of wallowing in amnesia, Britain’s professions and politicians do a bit of remembering what their predecessors were good at, a bit of learning from foreigners and a lot of innovation. This is a more optimistic view from about 2025.

Thames Gateway develops, but more slowly than in government plans of 2006. This is partly because major elements of government and cultural institutions have been spread to other regions, partly because other development corridors are evolving: through Watford, Berkhamstead and Tring to Milton Keynes and Luton; through Surrey and Sussex to Gatwick and through east Hertfordshire to Stansted and Cambridge. London’s old ‘green belt’ plan is being replaced with something more like the ‘finger’ plans of Copenhagen and Stockholm. Almost all those living in the new areas can leave home and walk one way to a good shopping centre and railway station, the other way to green space and allotments, stables or golf course. The choice between urban and rural situations is over: most people can have both, not just those in Hampstead, Richmond or Stanmore.

Within these new ‘fingers’ all the land has been taken in to the ownership of Land Development Trusts. They are very diverse but what they have in common is that they retain all the freeholds and grant building leases subject to ground rents which are annually revised in line with market conditions. This means that these collectivities gather about half of the growth in property values while the owner-occupiers or other users of land get the other half. It’s a fair exchange because this revenue covers all the costs of infrastructure and services, maintenance of ecological systems and community services. It is a good long-term investment and is financed with bonds which have proved very successful in an increasingly volatile world financial system. These have been investments in real things (infrastructure and service spaces) which actual people use and pay for so they are more robust than the highly speculative investments which the geographer David Harvey called ‘fictitious capital’ – investments made in the hope of capturing some imagined future profit.[2]

From about the year 2000, many countries – led by the USA – created a new kind of tax-exempt investment company for holding real estate – ‘Real Estate Investment Trusts’ (REITs) there and with other names elsewhere. These brought a lot of new money into property investment, mainly in shopping centres, offices and so on. But from about 2005, these funds began moving into the large-scale ownership of housing on the assumption that money could be made by speculative selling or by jacking up the rents being paid by tenants. In Germany many hard-pressed municipalities and social housing organisations sold thousands of (occupied, tenanted) dwellings to these investors, causing severe alarm. Following the rent strike against Real Estate Investment Trusts across the whole of Germany in 2008, international investors have switched from asset-stripping social housing to safer investments like this. The bond-financed equity-sharing system used in the London region from 2007 is a modified version of the site leasehold system which gave us Bloomsbury in the 18th and 19th centuries and many other high-quality urban areas in Britain. In those early cases it was a private owner who held the freehold and thus got the long-term benefits – indeed it was mostly aristocrats. But the system works as well or better when the long-term owner of the collective rights is a public or collective body with no outside shareholders. It is similar to the Hong Kong system which produced half the income needed by the colonial administration, enabling tax to be kept very low. And it draws on the lessons from Britain’s post-war new towns which Margaret Thatcher privatised just when the profits were really rolling in.

Another great innovation in the Thames Gateway has been in the configuration of street systems and shopping/service centres.[3] No longer do we have hierarchies of main and ‘distributor’ roads, with shops and services in isolated islands away from passing trade. Instead the frontages to main urban roads are all lined with shops, schools, offices and other services, with parallel service roads for cycles, buses, trams and cars. Passers-by can (and do) stop for services and everyone has shops within 10 minutes walk and a B+Q within 10 minutes drive. There is so much of this commercial space that rents for it are rather low and the new development areas have become a breeding ground for new business: only here can shopkeepers combine local customers, online customers and the regional customers who come and hunt them out. There are no double red lines here.

The London Plan has put a lid on further office development in and around the centre of London, just as Paris did to ensure that its suburban employment centres took off at La Défense and at Marne-la-Vallée. These two huge developments were not much use, however, to the impoverished residents of the working-class suburbs of Paris who have been widely excluded from the general economy – but they did show what could be done to make a region more poly-centric.

The British real estate fraternity were furious initially but now find there are plenty of good investments in these prospering London suburban nodes, and they are much less volatile than central London, which was all they knew about until about 2010. Communities living round King’s Cross, the Elephant and Castle and London Bridge breathed a sigh of relief and got on with life, the threat of displacement much reduced.

Because employment growth in Central London has slowed, more jobs are being created out in the suburban nodes. There is quite a bit of reverse (outwards) commuting so the trains are used in both directions. The massive investment in Crossrail was not needed and has been re-directed into a better network mesh of routes linking suburbs, using a mix of trains, trams and buses.

But probably the biggest transformation has been in housing. Barratt, Persimmon and their like, whose main skill was managing their land banks and timing their developments, have re-directed most of their work to Dubai and Shanghai. In their place we have a whole new industry based on cheap and plentiful land supply. Users of land pay over the long run through their ground rents (see above) instead of up-front. A consortium of Stuart Lipton, Ikea and John Lewis dominates the production of modular building components so that building enterprises get economies of mass production whether they are big or small. It is the modernist dream come true but with a thoroughly post-modern outcome: every dwelling can be different. Whereas new housing used mainly to be aimed at first-time buyers and new households, current output targets a huge range of market segments – often in the same development. So thousands of elderly Londoners have moved out of their big houses and flats where they could afford neither the maintenance nor the Council Tax and now live in the Thames Gateway. The key attraction for many of them was dwellings with few but spacious rooms, bookable guest rooms for visiting friends and families nearby, plenty of children and younger people around (but out of earshot) and an easy transition to more supported form of living as they get more decrepit. The housing associations, co-ops and developers which understood this, and the architects who helped them, have become immensely successful.

Image: Slogan on a site in Hackney: a workshop demolished to make way for luxury housing. Photo Michael Edwards 2005 Part of the buzz in the Thames Gateway comes from this shift away from totally individualised housing, highly popular with people in all age groups including young workers. The growth of co-housing and of various forms of cooperatives has produced both a revived sociability and a major reduction in the environmental impact of falling household size.[4]

Image: Slogan on a site in Hackney: a workshop demolished to make way for luxury housing. Photo Michael Edwards 2005 Part of the buzz in the Thames Gateway comes from this shift away from totally individualised housing, highly popular with people in all age groups including young workers. The growth of co-housing and of various forms of cooperatives has produced both a revived sociability and a major reduction in the environmental impact of falling household size.[4]

Another distinctive feature of development in the Gateway is the wide range of densities of building, ranging from 20 to over 1000 habitable rooms per hectare. All the developments have to meet a zero carbon emissions standard and all the low density developments have to make big net energy contributions to the local or national grid to compensate for the fact that their residents are bound to drive a lot more. A good example of the results is at Mucking in Essex where the high river terraces (with long views across and down the estuary) were intensely settled by Romans and Anglo Saxons in the first millennium. They were then removed by gravel quarrying in the 1970s and are now re-settled as a busy town, mostly below-ground, but with balconies, terraces and gardens on all the space not covered with photo-voltaic panels.

Conclusions

Thames Gateway is neither bound to succeed nor bound to fail. But it will be hard to make into a great success. It is not the kind of development which the property market, left to itself, would undertake. But government is determined to impose it on a reluctant market, aided by its success in securing the Olympics for 2012: the Games helps to keep the speculative housing bubble inflated and provides patriotic legitimation for state expenditure.

[1] A. Amin, D. Massey and N. Thrift, Decentering the Nation: A Radical Approach to Regional Inequality, Catalyst, London, 2003. Doreen Massey, to follow, in Soundings, summer 2006.

[2] D. Harvey, The Limits to Capital, Oxford, Blackwell, 1982.

[3] On this see M. Edwards, ‘City design: what went wrong at Milton Keynes?’, Journal of Urban Design 6 (1): 73-82, 2001, http://linkme2.net/9i

S. Marshall, Streets and Patterns, London, 2004, Spon; Space Syntax http://www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/research/space/overview.htm

[4] See J. Williams, ‘Innovative solutions for averting a potential resource crisis — the case of one-person households in England and Wales’ Environment, Development and Sustainability 8(3): 1 – 30, 2006.

M. D. Astor, 'The hedges and woods of Mucking, Essex', J. Panorama, Thurrock Local History Society, 22, 59-66, 1979.

T. Butler and M. Rustin (eds), Rising in the East: the regeneration of East London, London 1996.

M. Gordon,'Thames Gateway: sustainable development or more of the same?', Town and Country Planning, 63(12), 332-333.1994.

Mayor of London, The London Plan: the Spatial Development Strategy, London 2004.

C. Middleton, ‘The road to Mucking: How does a banana skin in a bin end up in Essex?,’ Evening Standard, 25 Nov, 1994, p. 10-12.

Michael Edwards <m.edwards AT ucl.ac.uk> is a specialist in property markets and planning at the Bartlett School, UCL, in London www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/planning. He is active in the London Social Forum on London planning issues. Blog at http://www.michaeledwards.org.uk

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com