Beneath the Paving Stones, the Desert

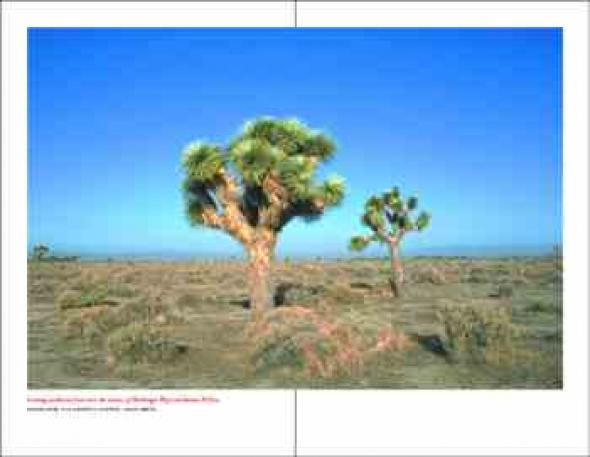

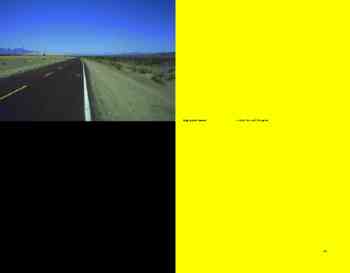

Rudy VanderLans is editor of the highly influential graphic design magazine Emigre and co-founder of the digital type foundry of the same name. He recently published Joshua Tree, the third in a series of books presenting photographs taken of the Southern California (SoCal) landscape. The trilogy was inspired by the music of the area’s legendary pop geniuses, including Van Dyke Parks (who collaborated with Brian Wilson on His masterpiece, Smile), Captain Beefheart, and flamboyant country-rock founding father Gram Parsons. Included with all of the books are CDs of music by Parks and former members of Beefheart’s Magic Band, new interpretations of Parks’ songs, and field recordings made in the SoCal area. Interview by Dave Mandl

DM: Emigre was at the forefront of the digital-design boom of the ‘90s and much of ‘90s art/design culture seemed to want to get as far away as possible from the physical body and the organic world. But your work in the California trilogy couldn’t be more different from that aesthetic, with very literal analogue photographs of the natural landscape, and simple, understated production. Is this a new direction or change of heart for you, a reaction perhaps to an overdose of digitality and technology?

RVL: Yes, to an extent it is a reaction to an overdose of technology, although make no mistake about it, these books are designed on a computer, the photographs are scanned by computers, and the books are printed by presses that were fully computerised. But I’m trying hard to make them look otherwise. So they’re also mired in the traditions of typographic convention and bookmaking, with much attention paid to the physical qualities of the book, which are still largely assembled by hand, such as the endsheets, head and tail bands, case binding, embossing, etc. I’m not interested any more in letting the technology dictate what to do, because when you allow that you run the risk of everything starting to look the same.

Furthermore, these books deal with a desire I have to connect with what is indigenous to California. I want these books to look like they were made in California. Lately, within my own profession of graphic design, I have sensed a serious decrease of work that feels indigenous, work that holds qualities that are particular to a certain region or country where the work is made. I see work from New York, Tokyo, Alabama or Singapore and it has become impossible to detect where it comes from. A good example of an artist who wears his immediate environment on his sleeve is Ed Ruscha. You look at much of his work and it just exudes Los Angeles. When you own one of his pieces, it’s like owning a piece of LA. That’s what I really like about Ed Ruscha, and it’s what I like to bring into my own work.

DM: After more than a century of industrialisation, the desert is still a constant presence in California; even in the densest urban landscape, it seems you can’t drive a mile without seeing it poking through somewhere. Do you think the omnipresence of the desert allows people to retain some psychic connection to the ‘real’ California, or to the natural world, even in a megalopolis like LA?

RVL: That’s a beautiful thought, and if you’re open to that idea, there’s much to enjoy in that regard. You can walk into the Santa Monica Mountains – in Will Rogers Park, let’s say – and if it’s a hazy day and you squint your eyes, and you look towards downtown, you may get a sense of what LA used to look like around the turn of the last century. But for the most part people like to pave things over. For many people in LA the desert is this stretch of no-man’s-land you drive through real fast on your way to Las Vegas. And developers seem to consider the desert, just like they did the valleys before, as the last cheap frontier to expand the outer reaches of LA into. I can’t imagine they have any interest in the natural world that surrounds them. I’m sure they’re very aware of it, but only in terms of its tremendous and often devastating powers. It doesn’t always easily comply with man’s need to pave it over. Floods, earthquakes, mudslides, ferocious heat and cold, and desert storms can make living in a desert environment a very unpleasant experience. Rattlesnakes and coyotes still find their way down the canyons into people’s backyards. To many, that’s simply a nuisance, not something to be in awe of or to connect to. It’s something to conquer.

DM: You talk about being drawn to sites with historical or ‘mystical’ (my word) significance for you – like the former sites of Zappa’s or Beefheart’s workspaces – even though they’re now populated by nondescript suburban buildings. Are there some kinds of ‘traces’ (‘ghosts’?) remaining in these places? Can they be detected? Can photos capture them?

RVL: This, to me, is the most exciting part of these photo trips. To see if anything is left behind that may hint at the greatness that these spots were witness to. Or perhaps to see what it is that attracted these artists to be in these particular places. That’s exactly the reason I go there in the first place. The expectations are huge, always. These trips are like little pilgrimages. Of course, it’s usually a disappointment. Most of the time there’s nothing there of any significance. But what makes these places interesting are the stories and histories that surround them. And that is what these books are about. They’re trying to extend the stories, or to keep the stories alive. Or, at the very least, to provide the stories with a visual backdrop.

Recently Van Dyke Parks took me on a tour of the locations and former locations of the major recording studios in LA. They are all housed in rather generic-looking stucco boxes without windows. But when I think what was created inside these boxes, it instils awe in me. Parks took me inside Sunset Sound and to me that felt akin to walking into The Louvre for the first time.

DM: How did you do your photographic expeditions? Did you do scouting or research of sites first, or were these random drives or drifts?

RVL: I have always paid much attention to Van Dyke Parks. He is such an interesting character – not just a great musician, but a great philosopher of sorts, with a serious interest in California culture and history. On my first visit to the Mojave desert, and in particular the fringe communities around the edges of the desert, I was just so taken by the environment I didn’t know where to start photographing. There was just too much. One day when I was listening to Parks’s song ‘Palm Desert’ I realised he was singing about an actual town called Palm Desert, which is on the edge of the Mojave just south of Palm Springs. And when I tried to figure out his rather cryptic lyrics, I realised he was singing about real estate development issues, mixed with his own experiences of living in LA. I then found out that he had actually written Song Cycle while living in Palm Desert. This is when my idea for the books started. I decided to go out and photograph Palm Desert, see what this place was all about. This allowed me to focus on a very specific subject, situated in an area I loved, while paying homage to one of my heroes. The route I took was roughly determined by the places Parks mentions in his lyrics. With Cucamonga and Joshua Tree I roughly followed the same pattern.

DM: Do you think there are remnants of the old SoCal landscape (which is being slowly replaced by faceless suburban homes) that are somehow preserved in these records? Do you see this music as a kind of time capsule, so that combining a listen to Song Cycle with a road trip through present-day SoCal helps bring the SoCal of thirty years ago back to life?

RVL: Not really. I have little interest in bringing these times back to life. That would be impossible anyway. But I am interested in showing what was good about them, and how things have changed. I think that, like all great art, an album like Song Cycle represents and preserves a particular time and place. Particularly the original vinyl version. It does this by the way it sounds technically, the way it was recorded, its physical qualities as a piece of vinyl, its subject matter, the artists and engineers who produced the album, and the designer and photographer who produced the cover. All these qualities are preserved in the record. It’s an artifact. And as such it has come to represent the California of 1968. But what makes an album like Song Cycle truly great is that the music transcends all this. It’s timeless.

To me, the three albums that inspired these books – Song Cycle, [The Byrds’] Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and [Beefheart’s] Trout Mask Replica – are the three most important pop music albums ever made. What I admire most about them is that they offer something original while remaining firmly grounded in the traditions of indigenous American music. While designing my books, I tried to echo that by looking back into my own profession, by looking at who came before – book designers like Jan Tschichold, type designers like Baskerville and Bodoni, photographers like Ed Ruscha and Walker Evans. Whether people notice it or not, these books, in a graphic design sense, all pay homage to the people who came before. Not so much to bring back these times but to say, hey look, there was some really good stuff done then, let’s build on it.

Dave Mandl <dmandl AT panix.com> is a writer, photographer, and DJ at WFMU-FM in New York City. He recently contributed the photographs to sound-artist Peter Cusack’s CD Your Favourite London Sounds

spreads and covers taken from the Rudy Vanderlans trilogy including: Palm Dessert // ISBN 0966940903 // $24.95 // 1999Cucamonga // ISBN 0966940911 // $24.95 // 2000Joshua Tree // ISBN 096694092X // $24.95 // 2001All published by Emigre Inc., Sacramento, CA // [http://www.emigre.com]

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com