In the Beginning was the Muwashshah

Ed Emery, translator extraordinaire of Italian literature and political theory, discusses his ‘personal key to the universe’: the ancient poetic form of the Muwashshah. For insights into Dante and the development of western culture in general, read on

I’m researching Arabic and Judaic cultural influences on the West in the times of Dante. Specifically, I am suggesting that the sonnet – which most people would regard as an exquisitely western form – was derived from Arabic poetic sources. So I’ve taught myself Arabic, I’ve taught myself Hebrew, and I spend my time delving around in dusty corners of libraries turning up amazing things.

Nobody talks much about these Arabic and Jewish poetic sources. But as I dig around, names pop up from the past. An Arab – Ibn Arabi, from Andalucia, a Sufi, a philosopher and a poet. A Jew – Abraham Ibn Ezra, also from Andalucia, and also a philosopher and a poet. And specifically a poetic form associated with them. It is called the ‘muwashshah’. Even the word is strange – even more so in its plural – muwashshahaat.

I like to be in this space. Deep in inner terrains of the unknown and the unknowable. But it has to be said that I am having problems with Islamic Arabic. Hard to know what is being talked about sometimes. Not least because the writers are forever using mystical double meanings for words, etc.

So anyway, I’ve been staying at a friend’s house in the East End of London. Coming back from the corner shop with a loaf of bread, freshly baked and crusty. At the curbside is parked a builders’ van. A couple of young men taking a lunchtime nap inside. As I walk past I hear music on the in-car stereo. Something about it catches my ear. It’s Rai music. Arabic stuff. So I walk over to the van window and I make myself known. Diplomatically, because you don’t just disturb snoozing builders on their lunch break. I say to the young man in the driver’s seat, twenty something in a baseball cap: ‘Excuse me... Can you by any chance read Arabic?’

And he says: ‘Of course, man. I’ve been learning Arabic since I was two.’

This is good news. Remarkable, even. But that’s not the half of it.

Tentatively I say: ‘Do you think you could help me with a bit of translation?’ And he says: ‘Sure man, no problem.’ So I explain that I need help in translating a muwashshah of Ibn Arabi... To my great surprise he says: ‘Ibn Arabi – I know him. Middle Ages. I’m a poet, you know. I write poetry. I’ve been writing poetry for years. Ever since I was at school in Morocco. I used to write muwashshah. Loads of people in my country write muwashshah. And then the big singers, they sing them, and it’s a great honour for the kids to have a singer singing their poems...’

So then I say: ‘I’m researching the Jews as well. I think they used to write muwashshah back in the Middle Ages.’ And he says: ‘Sure. I know about that. We have loads of Jews in Morocco. About twenty per cent of the country is Jewish. Even the King, he has a special advisor, and he’s Jewish. And the Jewish people in Morocco, they sing muwashshah too…’

Let me tell you, this is an emotional moment for me. An East End builder, twenty-something, knows about all this stuff which I thought was buried in obscurity. For him it’s the lived stuff of everyday life. And nowadays in Morocco you have Jews and Arabs singing the same songs, based on the old stuff. Just like they did in the olden days when Jews and Arabs lived together and wrote poetry together and shared cultural life together and helped lay the basis of western civilisation together. I join him in his van. We translate. But then the foreman rattles at the driver-side door handle, because lunchtime is over.

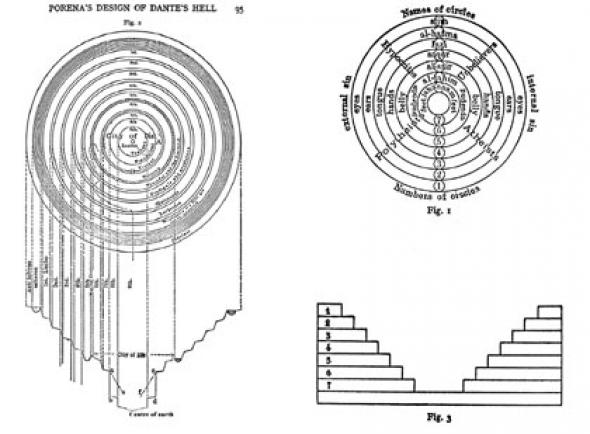

A job well done. I leave to go about my business. And the concrete outcome of my studies? This last September I’ve been organising a conference in Venice entitled Arabic and Judaic Influences in and around Dante Alighieri. I presented a paper arguing that there was a pan-Mediterranean medieval culture of the muwashshah which sang the praises of both the beloved and the divine. In Italy the sonnet emerges as a variegated and unruly subset of the muwashshah, and a 14-line version of that subset was created at the Arabising court of Frederick II in Sicily. That version was canonised by Dante and his associates, and it is the version that has come down to us. Voilà, tout.

We have a website for our Conference at [www.geocities.com/DanteStudies]. When I eventually complete my paper you will find it there.

Ed Emery <ed.emery AT cwcom.net> spends most of his time working for the communist revolutionary transformation of society

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com