Becoming Camwhore, Becoming Pizza

In the hot lava of social media flows the critical distance between performing and being a ‘somebody’, a subject type, seems to collapse, along with the ‘integrity’ of art’s own space and frame. In the lead up to their exhibition at Arcadia Missa, Web 2.0 artists Jennifer Chan and Ann Hirsch discuss the politics of performance and the productive nausea of networked becoming with art historian Cadence Kinsey and curator Rozsa Farkas

‘State and Lore (Revolutionizing Desire: A Reclamation of Representation for its Affective Potential) is a day of talks and performances hosted by Arcadia Missa at South London Gallery’s Clore studio. Conceived as an interdisciplinary event, State and Lore plans to bring together artists, writers and academics who are currently working through questions of representation and embodiment in relation to digital media and Web 2.0 technology. There will be a live piece by Jesse Darling, a performance by Ann Hirsch featuring excerpts related to her Scandalishious project, and a talk from Paul Kneale. There will be skype talks with Jennifer Chan and Faith Holland. The symposium has been put together in conjunction with And Lore, an exhibition of works by Chan and Hirsch at Arcadia Missa, a gallery, publishers and studios in Peckham, South East London.

Here, one of the speakers for the day, art historian Cadence Kinsey, talks to Rozsa Farkas, director of Arcadia Missa, and the artists Ann Hirsch and Jennifer Chan about the themes and intentions for the symposium and show.

Cadence Kinsey: From my understanding, Revolutionizing Desire has been conceived as a response to increasingly urgent questions concerning forms of representation, and especially self-representation, in the context of social media and other Web 2.0 technologies. With the ever-growing profile of what has been called ‘post-internet’ art, in which artists are questioning, problematising and redefining our relationship to this technology, it feels as though we are in the middle of some sort of moment of critical reflection. Histories of representation and the discourses of late capitalism are intersecting with social media in new and unique ways.

As the organiser of the symposium, Rozsa, I wanted to ask you about this notion of representation. It seems to me that many of the participants of the symposium are looking at questions of representation through the lens of performance. Particularly, Web 2.0 technologies feature prominently as a device for framing the performance of the body/self, and I was wondering about this collision between the ‘live’ body and the process of technological mediation. Looking at the artists involved with the symposium, we’re not simply dealing with images of the body, but a performative interaction between the body, technology and the viewer and/or user. What does it mean to situate performance online, and how does this not only change the terms of ‘performance’ as a category, but also work to shift the perception that there is a distinction between IRL and URL?

Rozsa Farkas: I would also say that there is a performative interaction between representation and technology. That the employment of social networks and video sharing platforms is a means to ingrain not only a performative manifestation of self online, but also to provide the site for an exploration of, or research into, the mode of representation of ‘the other’. This other is the disembodied representation of a person that is built via layers of social feelers and partial digital self-exposure.

So seeing performance, and thus self-representation, as being enacted through our communications with one another, there is a common aesthetic language that cannot be reduced simply to images, let alone images of the body. Instead, performance is about one’s presence or contact: an alignment to various representations like text, sound and image (all accessed through GUIs) that are also tools for the personal branding of one’s corporeal self(s). This is examined, not parodied, but actually lived, through the performative practices of the artists involved in the symposium.

When you say the distinction ‘between IRL and URL’ may be shifting, I feel that this is a nod to some of the most interesting artists working right now, who do not particularly see a distinction. Instead, both IRL and URL is, in a basic way, ‘our’ (western, connected, privileged) everyday reality. As an example, Jesse Darling’s show at Arcadia Missa in April this year actually pulled works out of her material environments, which she understood as relating both to social networks and Ikea. Likewise, Ann Hirsch’s work is often only whole when it is performed live, utilising realtime online interactions, and there are some similar sensibilities in Jennifer Chan’s work too in terms of the varying material manifestations of her projects.

Jennifer Chan: I don’t think there is a consolidated representation of me or one that is consistent throughout my work, in contrast to Ann, who uses disparate profiles to develop a recognisable digital persona. I am different on chat, on cam, and in real life. I have five tumblrs and three YouTube accounts and not all of them are linked to my name/website. I take comfort from the fact that the internet allows for that kind of performative fluidity. I think making websites is a performative thing too because many people assume the designers/web developers are male and I feel like I’m performing a quasi-web-designer-dude when I made Intimatecrust.com as an amateur fetish site to promote YoungMoney, or Totalrelease.org for promoting a ridiculous self-hypnosis programme to achieve orgasms in a non-sexual way. For a while I was making non-sexual fetish videos because I was fascinated with those communities online and what they considered sexy. Besides titillating the fetish community to draw hits to my main YouTube account, I was combining different fetishistic gestures to present them as art because I felt they looked like durational performance art. In videos like Screen Saver I combined them to express some sort of fetish for technology. For some reason those videos made me appear sexually deviant or passive and I received requests from people on YouTube (which I’m sure Ann has experienced too). I somehow felt performance wasn’t enough to destabilise the dichotomous ways people viewed women as sexual subjects online so I began working more with found media. For me remix is a way of recontextualising signifiers of net culture from a female perspective.

Images: Jennifer Chan, Young Money, 2012

Ann Hirsch: When I started performing Scandalishious on YouTube in 2008, I was excited about the potential for women to start creating imagery of themselves online, in ways they couldn’t with traditional media such as film, TV etc., because they were harder to gain access to. In this way, we could redefine the stereotypes of ourselves – break them down, change and subvert them. Also, I was in graduate school in upstate New York so I didn’t have access to galleries or an art audience either. So the only way I could make work for a lot of people to see (besides my small community of peers and teachers at school) was to broadcast online. It was a fairly experimental process and while I had sort of utopian ideals going into it, I found that ultimately and obviously, people are going to come to your work with their own notions, their own prejudices of what it is that you’re doing. So to perform online means letting go of a lot of the control you might have over a piece that is just for an art audience. You have to be OK with allowing endless replication and appropriation of your work and having to deal with instant, often negative, feedback. And finally, simply handling what it means to have your body online when the majority of bodies online are in pornography. I believe that whenever you put your body online, in some way you are in conversation with porn.

CK: Thinking about the artists who are participating in the symposium and the Open_Office programme at Arcadia Missa more generally, what occurs to me is that technology is very much used as a framing device, a way to situate the performative practice in highly specific political, social and economic contexts. There is a real investment in the context in which works are being produced, distributed and seen, in a way that wasn’t always the case. In the ’50s and ’60s artists working with film tended to disassociate themselves from the languages of Hollywood, developing an aesthetic that designated their work as ‘experimental’, ‘expanded’ or ‘structuralist’, for example, Stan Brakhage, Maya Deren, Carolee Schneemann or Anthony McCall. Their work is identified by its dissimilarity to Hollywood film and, more importantly, was not broadcast in public theatres. Even when we get to the ’70s, the artists and organisations who did actively engage with the context of television, by using public access TV (such as Martha Rosler, David Hall, Ian Breakwell, Richard Serra, Nancy Holt), still did so using a visual register that immediately signalled to the viewer that there was some kind of critical distance occurring between the text and context. When I think about Martha Rosler ReadsFrom Vogue for Paper Tiger TV (1982) it stays on the side of critique: there is a clear division between text and context. Now, many practices are engaging in a really extreme, parodic mode of representation. Ann Hirsch’s work, for example, not only looks like all the other videos of girls dancing in their pants that you might find on YouTube, but is also situated right in amongst them.

RF: You are right; this question of critical distance is something I am increasingly worried and confused about, and is something that we try to touch on with the editorial notes insert in issue 3 ofHow to Sleep Faster (Arcadia Missa’s journal). I think that the possibility for aesthetic distance and criticality, whilst remaining within the belly of the beast, is a key point that we want to discuss in the symposium. Tying this to performative practices is interesting, because using parody or performative fiction, or even lived experience can provide criticality within the same context. Fetishising sportswear or making art that looks like corporate logos and then uses that image currency for self identity can’t be critical to the same degree. I really am into this kind of performative work, when it critiques late Capitalism’s production of lifestyle and hyper-specialised cultures.

And yes, Ann’s work really gets close to the line, in fact it crosses it, but at the same time it also opens up a new critical space as it operates within the language and context of ‘cam girl’, or whatever you would call it, yet brings up the contrasting and conflicting expectations of how one should present one’s identity. It subverts binaries such as sexy/slutty as there is a genuine exposure of the tension and the prescribed ‘impossibility’ of owning and simultaneously engaging with both parts of the binary. When a critical distance is presented but published in the same context it is often much more ineffective than in Ann’s work. An example of another performance within URL contexts which arguably suffers from a ‘failing’ affectiveness can be seen in the work of Natacha Stolz which makes use of the same context but has triggered quite a backlash [see:http://ohinternet.com/Interior_semiotics].

JC: I would agree with this tech-as-context (not content) approach. I see my work manifesting as a voice directed towards different, confused female subjectivities which are produced by some half-internalisation of netporn or standard of how women should behave online. This is always followed by some disruption of those expectations (i.e. in factum/mirage I look like a camgirl who is going to take her shirt off in live video chat, but a pre-recorded part of the video makes it apparent that the video is a looped prank). While most of my other work is informed by user culture, Joan Jonas’ Vertical Roll(1972) was a direct inspiration for me in terms of that piece.

Found footage remix is a powerful tool for talking back to the status quo because found media can be employed against its intentions and also repeated to the point of deconstructing desire. (Another early example is Dara Birnbaum’s Wonder Woman (1978)). Not all my videos are about being a woman per se but I think they come from a confused female reading of existing messages on mediated masculinity and femininity. There’s a large female vidding community and also an online political remix community that’s more progressive and supportive about conversations on gender than the contemporary- net art one in my opinion. In my work I use found footage and recorded footage to create mixtape-like remix videos that people can watch if they’re bored.

Also, in light of entertainment-saturated politics and the ad-driven internet I believe that critique must be delivered in a seductive ‘dumb’ way to keep audiences watching (hence the hip hop music and cute graphics in Young Money, which is both a fantasy and satire of ‘brogrammer’ culture on the web and in new media art). Not everyone will understand the highly specific references as they pertain to cyberculture, like red bull and pizza, but I think it’s important to use silliness to say something serious so that people are sufficiently annoyed and attracted by irreverence to continue (hopefully unquestionably) watching.

I have a complex love-hate relationship with things like netporn and mainstream hip hop which have really catchy backbeats but are rife with misogyny and glamorised violence. I am also fascinated by the cultural flows and hybridisation of aspects like ‘swagger’ and hustling to other non-Black male prosumers of hip hop. Young Money doesn’t make the latter explicit even though the two skyping guys are talking in ebonics on skype, but those ideas were on my mind.

A similar work that predated mine and was made by a non-artist is Chris Korda’s I Like To Watch(2002), where 9/11 plane crash footage, masturbation and porn are juxtaposed to critique the effect of negative news – you hate it but you can’t stop making yourself miserable with watching it.

AH: The Scandalishious Project not only looks like all the other videos of girls dancing in their pants that you might find on YouTube, it IS that. People are often mistaken in thinking I am critiquing or parodying the girls who are on YouTube dancing or monologuing. I am not. I am joining them. TheScandalishious Project was a journey in which I tried to undo my own notions of what it means to be a ‘respectable woman artist’. I was told by professors I was too ‘smart’ to be making ‘that’ kind of work. That is precisely the kind of slut shaming I was exploring with that project. On the flip side, I was also looking at the realities of what it means to put yourself out there, how it affects you, how you’re perceived. The project was really more social research than some sort of collective video display. The parts of The Scandalishious Project that you can see online is just one façade of the project. The other side of that façade are my ‘findings’ as I call them, which is the interactions I had with people, the videos I received and my own internalisation of the process of becoming a camwhore. People who come to the conference will get to see some of those ‘findings’ during my performance piece.

Images: Ann Hirsch, still from Caroline in the Gallery, Digital video, 2010, 50'00

I did a similar thing when I became a contestant on Vh1’s reality dating show Frank theEntertainer...In a Basement Affair. The idea, again, was not to critique the individual women who were participating in the show, as often times viewers like to do, but critique the system that manipulates them and then shames the women for allowing themselves to be manipulated. I wanted to understand what it meant to be one of these ‘famewhores’, since for so long that was something I never would’ve allowed myself to be because that title carries such shameful baggage in our culture.

Knowing the way a system works, being able to understand why people do the things they do and being able to empathise with them is the most powerful vehicle for change. Productive critique can only come once that has happened.

CK: What does it mean to work within such a frame or ideological context; knowingly working in a space that straddles the public and the private; willingly becoming ‘prosumers’.

RF: I think this is part of the shift between TV as mass culture to Internet becoming mass culture – like I said, for the first time you can instantly exist and present work in the same context, it’s not just about using the same media. Prosumer culture and the ‘everyone’s an author’ culture has come under fire from those who were among the biggest supporters of the early internet (such as Jaron Lanier) – and in terms of contemporary artists’ practices it is worth looking at this shift and pondering if and when it is a product of the social environment as opposed to a change in desired media. This sounds rather harsh, but what I mean here is ‘we’ (cultural producers, and in particular artists) are symptoms of our contexts, blindly prosuming, enacting and reinforcing, as Lanier puts it, ‘digital maoism’ [the belief that the the collective is all-wise].

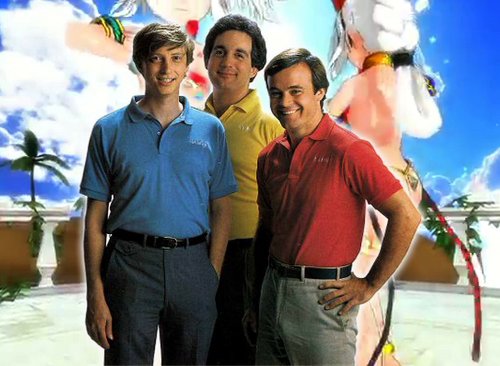

JC: I believe these cultures (internet culture and TV, or more broadly, the culture around the screen) are intermixing. Realist codes are informing user-generated media, and users are also producing music videos and personal documentaries that look really professional. I see artists (like me and also Angela Washko, Elisa Kreisinger and Anita Sarkeesian) taking those two contingencies of prosumer tech and using it as a style to say something about how people see and treat each other on the web.A Total Jizzfest is a video made in the style of a fan video or a vid, as the vidding community would call it (that’s the practice of re-cutting images of films and TV shows to a song they like to produce new personal narratives as a way of appreciating the original text). But instead of film or TV images I chose images of men who were important in computer and internet history. These guys are rather dorky; Bill Gates and his team are wearing mom jeans. The second part with ‘Oh boy’ by Cam’ron features young hip web 2.0 internet moguls. There’s some kind of fangirl objectification through the fake-naive sequencing. Like Young Money, attraction to these men is coupled with dissatisfaction at the lack of women in these fields.

CK: In addition to parody, appropriation has also emerged as a line of investigation for many artists. But how does appropriation function as representation, especially self-representation? Appropriation seems to channel the image of the body/self back into the political, social and economic networks in which it was produced – and here I am thinking of the re-blog, in which it is the perpetual de- and re-contextualising of an image, its very movement, that generates capital.

RF: Exactly. And it’s really great you brought this up. This idea of the reblog is pertinent to my thoughts around presence or soft touching via liking/reblogging/tagging, and the dematerialisation of art, which embeds our corporeal selves in a currency of speed through the quick touching of references: all is liked and dissipates. Like you said, this has a direct relation to capital, and the velocity and presence of an image also creates cultural capital and its forms. To be able to subvert or harness this to effect, or to see how visual representation can still be affective, whether it can provide and distribute critique of society is why it is important to look at appropriation as representation.

Appropriation isn’t new, it’s gone through many forms. Was the readymade really a massive political gesture or have we appropriated desired histories too? The (positive) divisiveness which reveals its potential here is incredible, it all boils down to different abilities to communicate an idea.

I feel that a statement can no longer as easily be made via the appropriation of one thing put into an ‘alien’ context, because reblogging is all about an image’s value being based on its ability to exist within any context. And yes this is much more closely embedded within the capital behind the screen as you freely share and take. It’s not an apolitical or money free space even if the ‘flatness’ of an image means it proposes an apolitical, asexual and a-aesthetic quality. The context is not just the website it sits in, it is society ‘at large’.

JC: Appropriation seems to be a given process in net art – maybe because everything appears to be in the public domain (though there’s legal language around ‘fair use’ governing the degree to which it’s acceptable). I’d like to quote Oliver Laric’s Versions 2012 video. The final line declares ‘Hybridize, or disappear.’ There is a sense that if an artist doesn’t incorporate or address pre-existing ideas they will fall behind in currency or information value. In the lowest-common-denominator way of thinking about it, reblogs/appropriation shows the surfer-artist is aware of a media text’s existence.

CK: It is impossible to talk about representation without speaking about the contextual specificity of the body/self at stake. One strand of this discussion, which emerges very strongly for the artists that are participating, is concerned with both gender and the sexed subject.

JC: I won’t lie; in Young Money the white male body was cropped and instrumentalised to the female gaze and for a feminist critique of the ‘cumshot’. This gesture (ejaculating on a woman’s face/body) is a common trope in netporn which signifies the end of a scene but also seems to demarcate an object or body as territory for the outlet of male pleasure. However, the decision to leave the male subject faceless was informed by the performer’s comfort levels. He was comfortable with showing his genitalia online, but not with showing his face. There was a bit of size-shaming directed at the video, and it comes with expectations of pornified online masculinity. We agreed that passing a handheld camera back and forth would be a sympathetic perspective from both male and female POVs, and having a webcam and HD cam shooting long shots would offer multiple perspectives.

I wanted to offer an alternative to the ending-as-climax by wearing the pizza-patterned shirt that the faceless male subject ejaculated onto. It’s both a critique and trivialisation of ejaculation – to show the directing female subject as neither pleasured nor disgusted while posing in the shirt. I think the presence of cock on chat forums is banal for women users who frequent these spaces too. The pizza-patterned shirt is Sterling Crispin’s art project from PizzaShirt.net :). It seemed like the perfectly hip commodity to turn into metaphor for male body/desire. Sex sells and porn was crucial to the growth of the early internet after all. I think this is why it was important to incorporate that self-as-subject performance into the remix video about guys on the web to show that I, as a thinking sexual observer-subject, have a way of identifying and rejecting certain aspects of porn, and to show those tensions between mediated and carnal experiences of the sexual self. In Young Money, prosumer video technology (screen-recording software, flipcams and webcams) are a means of representing the intersubjectivity of watching each other homosocially or heterosexually.

Image: Jennifer Chan, A Total Jizzfest, 2012

AH: In the live performances I do about The Scandalishious Project, one aim is to not only to create empathy for myself as a disgruntled camwhore but also give humanity to the men who enjoy camwhores. The project is ultimately about a mutual loneliness and desire for attention, where I delineate between how feminine and masculine gender roles influence how we go about getting it.

CK: I think an important question to end on is perhaps the relationship between critique and criticality. So far we have discussed parody and appropriation as strategies of critique – critique of the dominant ideologies that they (re)deploy – but it is also vital to talk about the possibility of, or space for redemptive modes of production and engagement. Perhaps this is where the potential of the aesthetic encounter comes in; a space in which the subject encounters him- or herself through the image?

AH: I briefly touched on this earlier but I think the creation of new imagery of ourselves, that tries to get as far away from the stuff we see on television, in films etc., is one way we can work towards change. The beauty of the internet is that we have these multiple platforms and different ways to express ourselves, so I do see the possibility there to work towards more complicated versions of ourselves, that aren’t limited to conforming to gender stereotypes. Inevitably, new stereotypes arise but hopefully they are better than the ones that came before them and ultimately lead to a greater public awareness.

JC: While I’ve become quite interested in how masculinity is expressed, defined and affirmed online, Angela Washko and Anita Sarkeesian also make work that analyses tropes of masculine/feminine representation in videogames. I think their visual discourse is more typological and accessible, whilst my work is more sensational about confused interpretations of masculine and feminine.

Remix and media-sharing platforms allow people to create and share alternate versions of reality, to respond and talk back to popular media. I’m siding with the political remix community that one should be careful with reappropriating content – so as to not repeat or glorify the disempowering representations we already see, and if we are, then capitalising on old ones to depict them as nuanced and complex. Found footage remix is also a way to be ideologically seen and heard without being physically present in the work if the author doesn’t want to be.

Ann Hirsch is a video and performance artist engaging with the contemporary portrayal of women in media, www.TheRealAnnHirsch.com.

Jennifer Chan is an an artist who works with video, performance and web-based media,www.jennifer-chan.com

Cadence Kinsey wrote her PhD thesis on the interrelationships between gender, technology and contemporary art practice. She currently lectures at Imperial, the Courtauld Institute of Art, and UCL, where she works with scientists, art historians and artists on a range of topics related to the techniques and technologies of representation and perception. Her research on digital technology is forthcoming in the journal Signs

Rozsa Farkas is the founding director and co-curator/editor of Arcadia Missa gallery, studios and publishers based in Peckham, South East London.

Info

'And Lore' (15 November - 25 December), a duo exhibition by artists Jennifer Chan and Ann Hirsch, has its launch as part of an all day event on Saturday 17th November, consisting of a day of talks and performances ‘State And Lore (Revolutionizing Desire: A Reclamation of Representation for its Affective Potential)’ with guests including Jesse Darling, Cadence Kinsey, Paul Kneale and Ann Hirsch. Moderated by Josephine Berry Slater and taking place at South London Gallery's Clore Studio. Please email rozsa AT arcadiamissa.com for more information and/or to request a seat to attend, as it is a guestlisted event. The launch day will then continue at Arcadia Missa Gallery from 5pm amongst the 'And Lore' exhibition with drinks – all welcome/no need to reserve a place.

http://arcadiamissa.tumblr.com/

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com