Art Strikes: An Inventory

What does it mean to strike art? A recent upswing of 'art strikes', from the actions against Trump’s inauguration, to the covering of works of art in solidarity with the global climate strikes, has been accompanied by the reappraisal of actions from the past, like Lee Lozano's General Strike Piece. For May Day 2020, Stewart Martin has assembled every case he could find, in the hope that it will offer some answers

The historical record of strikes has found scarcely anything of note in the actions of artists, except where they have contributed to the strikes of others. This is not far from the truth, but it does disregard a number of artists’ strikes – a number that has been rising in recent years. They remain comparatively rare and obscure, although their significance in the art world is fairly well established. And their status as strikes is often problematic or gestural. There have been some attempts to record them, but these are partial and/or outdated.1 The following is an attempt to provide an exhaustive inventory. It is the most extensive by far. It was prepared over a period of several years in order to identify the foundation stones or rubble out of which a speculative book on the art strike can be written. That is forthcoming. The inventory is published here in the belief that it can stand alone and possibly thrive. The hope is also that it will invite additions that might have been overlooked.

A few points on method are needed to avoid confusion. Each case is described according to conventional listings of strikes as far as possible. Information is provided where available on dates and location, demands and tactics, organisers and participants, failures and successes. The entries are minimal and factographic, albeit in conventional prose. Interpretation, reflection and speculation have been excluded, as has contextualisation, except where it is needed to explain primary information. The length of entries varies considerably, but this reflects complexities and available information, not importance. No judgements on importance are ventured here. The strikes are listed chronologically, but no attempt is made to offer a historical narrative. This decontextualisation leaves much unsaid, but it also enables the strikes to appear in close proximity, exposing their peculiar relations to one another. To this end, influences between the strikes are indicated where known.

It must be noted that the principle of inclusion deployed is primarily terminological. This is an inventory of all cases that appeal to a strike of art. Synonyms like ‘work stoppages’ are included, but boycotts, pickets and other actions often associated with strikes are excluded, unless they are explicitly characterised as a strike, which is often the case here. The focus is then on the peculiar characteristics of strikes of art, since this occasions desires and frustrations that are significantly distinct and more problematic than other actions. A boycott or picket of a museum does not present the same challenges as a strike.

This terminological principle also explains the inclusion of calls, some never enacted, some scarcely public, and even artefacts announcing such strikes. The reason is simply that the cases satisfying a more orthodox criterion of strike action, such as the collective withdrawal of employees, are vanishingly few. Arguably, only the strikes of the Federal Art Project and the Disney studio would count. Even according to a broader criterion, not many strikes were actually undertaken; they remained threats or unanswered calls. The inventory is then more a record of discourses than actions.

There is a certain abstraction involved in this principle: some cases appeal to a strike of ‘art’ or a strike by ‘artists’ in the traditional sense of the sphere of free or non-applied visual art, formerly dominated by painting; but several cases appeal to ‘art’ and ‘artist’ in an expanded sense; and some to a sense that radically rejects this tradition. In this and other ways, the art strikes are far from homogeneous and present profound distinctions and contradictions. Nonetheless, ‘art’ and ‘artist’ still tend to indicate this tradition or its ruins, rather than another sphere of the arts, such as a theatre or actors strike. The exceptions are perhaps the Disney and Federal Arts Project strikes, which involved a fairly traditional designation of applied arts. They could be excluded as anomalous. That orthodox inventory of art strikes would be then completely empty. But they are also exemplary for some of the other art strikes, so their inclusion is significant.

What characterises the art strikes is then a peculiar struggle over the very ideas of art and strike. This presents challenges inventorying them, but it also reveals an inventory of this struggle.

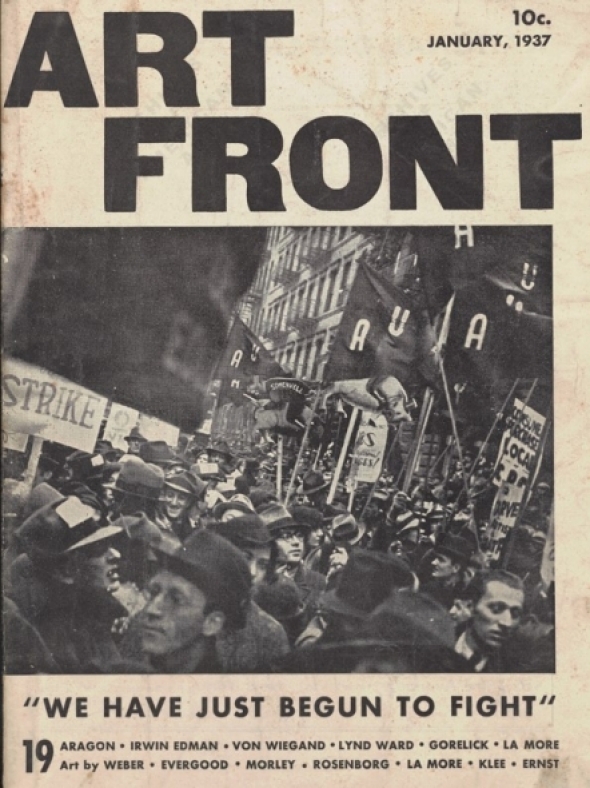

The Artists’ Strike at The Masses

In the spring of 1916, a ‘strike’ was threatened by the artists working on the socialist magazine, The Masses. Their general grievance was that the magazine had become dominated by a propagandist editorial policy, imposed by the editor (Max Eastman) and managing editor (Floyd Dell), which curtailed the contributors’ freedom. The strike thus assumed a struggle between the freedom of art and propaganda. More specifically, it concerned the appendage of captions to pictures without the artists’ consent.

At a meeting to resolve the dispute, the artists (including John Sloan, Stuart Davis and Glen Coleman) demanded the abolition of the positions of Editor and Managing Editor, and the reorganisation of editorial procedures to enable Contributing Editors, whether artists or writers, to have the final decision on content.2 These demands were rejected by Eastman as unworkable and he threatened to resign if they were implemented. He also disputed the artists’ appeal to a strike, pointing out that he and Dell were the only employees as such of the magazine, hence the only ones who could strike. However, he also conceded that he was, in other respects, in the position of their boss, granted the power to close the magazine by virtue of the fact that it survived on funds that he raised. He offered to continue as fundraiser, but on commission. A vote was held, but was tied. At a subsequent meeting, the artists were voted down.

The dispute appeared to end amicably with the re-election of the artists to posts within the magazine. However, Sloan changed his mind and resigned the next day, followed by Davis, Coleman and, the writer, Robert Carlton Brown. To replace the artists, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, G.S. Sparks and John Barber were elected to the magazine.

The Federal Art Project Work Stoppages

On Wednesday 21 August 1935, a two-hour ‘work stoppage’ was undertaken by artists employed in New York City by the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The aim of the stoppage was to reverse wage cuts to FAP employees and, more fundamentally, to reverse the reduction in funding for the WPA behind the cuts. It also aimed at an entrenchment or radicalisation in the artists’ tactics.

The WPA was established in May 1935 by the US Federal Government in response to the Depression, aiming to provide state employment, rather than dole.3 The vast majority of this work was in the building of streets, bridges and housing, but it also provided employment in numerous other areas, including the arts. The New York City FAP was a regional, albeit the largest, part of a nationwide programme within the WPA to support the visual arts – from painting and sculpture, poster and stage set design, to photography and various crafts, as well as related teaching, research and technical work. This was one of four projects established to support the arts more broadly, collectively known as Federal Project Number One or Federal One. The others were dedicated to music, theatre and writers.4

The work stoppage was not undertaken by employees of FAP alone. They were acting in concert with employees of all the Federal One projects in the city. The stoppage had been the resolution of a meeting the previous week of the City Projects’ Council, which represented workers on Federal One. Reportedly, 1,500 attended the meeting. Nonetheless, FAP employees and the Artists’ Union, which had emerged as their representative, were a particularly militant constituent. According to the editors of Art Front, the principal organ of the Artists’ Union, the Council’s decision had been inspired by the arrests of 83 artists on a picket line earlier on the same day of the meeting, 15 August.5 On 21 August, besides the work stoppage, it was agreed to form a picket line outside the offices of the WPA.

The Artists’ Union was formed in February 1934, after changing its name from the Unemployed Artists Group established in the summer of 1933. The Union regarded the Federal One projects as, not an emergency measure, but the inauguration of a new socialist era in support for the arts that should be made permanent. By the autumn of 1935, its membership was 1300.

Over 1,000 participated in the picket line, according to Art Front. The number participating in the work stoppage is not reported. The effects of the work stoppage alone are probably impossible to isolate from the picketing, both on the day and before, but the combination of actions proved to be successful. The November issue of Art Front reported the granting of a $13 bonus the next day and a 10% increase two weeks later.

On 9 December 1936, FAP employees in New York City participated in a half-day work stoppage, joining employees on all Federal One projects in the city. It is estimated that a total of 2,500 participated. The strike was the culmination of a sequence of protests and actions that autumn, which were undertaken against cuts to the WPA and pending dismissals that President Roosevelt had sought on the grounds that the private economy had now recovered sufficiently to begin to reabsorb workers from the WPA. This included the notorious action on 1 December, when 400 assembled to demonstrate outside the FAP offices in New York City. 225 then managed to enter and occupy the offices, staging a so-called ‘sit-in demonstration’ or ‘sit-down strike’. The police were called and proceeded to violently break up the sit-in, injuring 12 and arresting 219, all of whom were given suspended sentences for disorderly conduct at a trial on 3 December. The work stoppage, presumably in combination with the other actions, proved effective. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia made an emergency trip to Washington, which resulted in a suspension of the dismissals.

On 27 May 1937, employees of the FAP in New York City undertook a one-day work stoppage together with employees from all the Federal One projects in the city in response to further cuts to the WPA funds and threatened dismissals. It is estimated that 7,000 of the total 9,000 employed participated. This included a hunger strike at the Music Project headquarters, where pickets carried placards reading ‘Hunger Strike Against Hunger’, and chanted the number of hours strikers had gone without food.6 This was followed, on 28 June, by 60 occupying the payroll office for the Federal One projects in the city. On 30 June, 600 occupied the Federal One main office in the city, holding captive the head administrator, Harold Stein, in an effort to convince him to seek concessions. Stein agreed and concessions appeared to be secured, but were quickly reversed.

The militancy of FAP employees and those on the other Federal One projects had proved effective. It has been calculated that, ‘while employment on the WPA as a whole decreased by 11.9 percent from January to June 1937, employment on the four arts Projects increased by 1.1 percent’.7 However, the pressure to cut funding for Federal One and the WPA grew, and in the spring of 1939 congressional moves to liquidate them began to make progress. They continued for another four years until 30 June 1943, when Federal One projects came to an end with the termination of the WPA as a whole

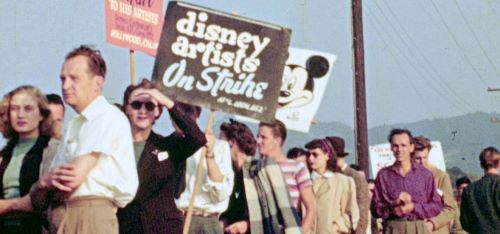

‘Disney Artists on Strike’

On 29 May 1941, around half of the 1000 employed at Walt Disney Productions in Burbank, California, began a strike over inequalities in pay and privileges.8 Amongst the picket line placards captured in photographs of the strikers, are a few announcing: ‘Disney artists on strike’. One shows an angry Donald Duck brandishing a placard that reads: ‘Disney artists on strike for union recognition.’ In a leaflet issued later in the protracted strike to combat rumours that it was over, is the declaration: ‘472 artists are still on strike!’ And: ‘The strike is not over until the artists return to work.’9

The strike was called by a meeting of members of the Screen Cartoonists Guild in response to Walt Disney firing 24 employees for membership of the Guild and union activities, including one of his most prized and best paid, Art Babbitt. The Guild was formed in 1936. In 1940, it became a branch of the Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers. By the time of the Disney strike, the Guild had secured contracts with the other major animation studios, albeit after a five-month strike at the New York-based Fleischer studio in 1937, and a six-day lock-out at the Schlesinger studio, resolved just as the strike at Disney commenced.

The strike at Disney held strong. It was supported by employees at other studios. A boycott of theatres showing Disney films was also launched. The strike finally ended on 14 September, with Disney signing a contract in agreement with the Guild.

Image: Still from John Hubley’s film of strike at Disney studios, 1941. Copy held at UCLA Film Archive

The Artist Tenants Association Strike

In June 1961, the Artist Tenants Association in New York City decided to organise an ‘artists strike’, although it was also referred to as a boycott.10 The decision was a last resort in the Association’s efforts to prevent the eviction of artists from their homes and studios in SoHo lofts by the City Fire Department, which had judged them unsafe after a series of fatal fires in 1960. The Association called on artists to withdraw from any public activity in the city, including exhibiting, lecturing or appearing on TV or radio, as well as attending exhibitions at galleries and museums. It also requested that artists withdraw works on loan or consignment, and not even show works in their studios. Artists living outside the city were also encouraged to support the action. The Association pledged to enlist as many as possible of the city’s galleries.

The campaign around the strike sought to draw attention to the culturally and economically devastating effects of the eviction. Amongst the famous artists pledging support for the strike were Jasper Johns, Alex Katz, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Fairfield Porter and Ad Reinhardt. The Association’s general cause also won support from prominent patrons of the arts, such as Eleanor Roosevelt. The protracted campaign threatened the strike would commence on 11 September 1961.

But it never came to pass. At a meeting in August the Mayor, Robert Wagner, agreed a policy of conditions under which artists could continue using the lofts as residences. These included the provision of two exits, the absence of excessive fire hazards and the placement on the building’s exterior of an 8 by 10 inch sign reading, ‘AIR.’ – in other words, ‘Artist in Residence’.

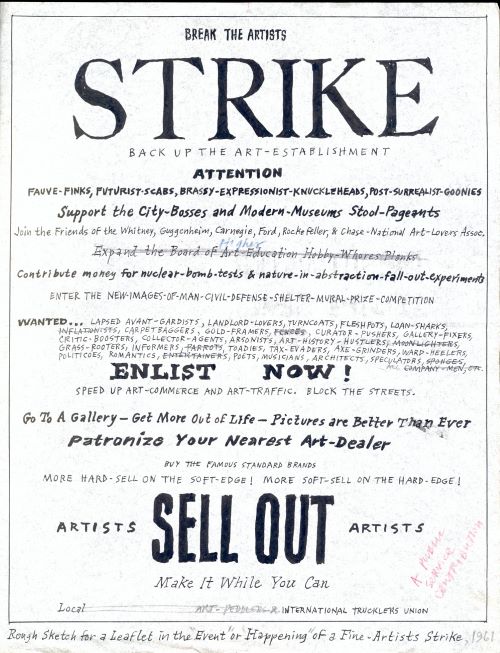

Reinhardt’s Leaflet for a ‘Fine-Artists Strike’

In 1961, Ad Reinhardt produced a ‘Rough Sketch for a Leaflet in the “Event” or “Happening” of a Fine-Artists Strike’.11 He never published it or prepared a more finished version. It entered the public realm sometime after his death (in 1967) as an artefact from his estate.

The sketch is satirical. It ridicules a corrupt art world by pretending to call on a grotesquery of artists and affiliated rogues to defend it. This much is clear, however the characterisation of the actual strike is peculiarly ambivalent. The leaflet appears to call for a strike. ‘Strike’ is set largest, and appears to be the subject of emboldened calls for ‘attention’ and ‘enlist now!’ The second largest and stand-out line is ‘sell out’, suggesting the strike itself is a call to sell out, along with all the other actions described, like ‘Patronize Your Nearest Art-Dealer’, ‘Support the City-Bosses and Modern-Museums Stoll-Pageants’ and so on. The leaflet is attributed to the ‘Local Art-Peddler & International Trucklers Union’, but none of the actions correspond to what might be expected from a union. The only exception proves the rule: the call to ‘Block the Streets’ is prefaced by the call to ‘Speed up Art-Commerce and Art-Traffic’. All these connotations suggest that the strike is the perverted act of a corrupted art world.

And yet, despite all of this, there remains the somewhat inconspicuous first line: ‘Break the Artists’. This clearly indicates a group of artists against which all the other artists – the ‘Fauve-Finks, Futurist-Scabs’ and so on – have been mobilised. However, what is thoroughly ambivalent is how the first and second lines relate. If they are read as two propositions, then the injunction to strike is consistent with the injunction to break the artists, which is generally consistent with strike’s connotations indicated above. But if they are read as one proposition, then the strike takes on a dramatically different and opposed significance: ‘Break the artists strike.’ The leaflet would then appear to be a call, not to strike, but to break a strike by these other artists. As it says of the ‘Futurists’, it would be a call to ‘scabs’, strike breakers. The perverted image of the strike would then be dissolved. But this would also mean that the leaflet talks only of actions to break the strike, and says nothing of the strike itself, except that it exists.

Image: Ad Reinhardt, Satirical Sketch for an Artist Strike, 1961. Ink; 26 x 21 cm. Ad Reinhardt papers, 1927-1968. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

The strike, whichever way one views it, is fantastical. The suggestion in the sketch’s title that it is anticipated appears to be yet another layer of fantasy. However, Reinhardt’s involvement in the Artist Tenants Association strike the same year suggests it somehow informed the sketch, although his support for that strike is difficult to discern from the sketch’s ambivalence.12 Reinhardt was also employed on the Federal Art Project and presumably involved in its strikes, but any influence they might have had on the sketch is unclear.

Jouffroy’s ‘Active Art Strike’

In 1968, Alain Jouffroy made what is widely assumed to be the first call for an art strike in his essay, ‘What’s To Be Done About Art?’

It is essential that the minority advocate the necessity of going on an active art strike, using the ‘machines’ of the culture industry so that we can more effectively set it in total contradiction with itself. The intention is not to end the rule of production, but to change the most adventurous part of ‘artistic’ production into the production of revolutionary ideas, forms and techniques.13

This call does not appear in an announcement or plan of action with an itemisation of demands. It appears rather within a comparatively discursive and reflective essay, albeit also passionately committed to action and tactics. The strike itself is only addressed explicitly once, as above, but it could be considered pivotal to the whole text. Jouffroy evidently conceived of the strike to characterise the revolutionary artistic initiatives of May 1968 in Paris, as well as the revolutionary currents he saw flowing into and from that moment.

The strike is presented as a strategy to be undertaken immediately (writing in August 1968) and anywhere possible. Its aim is social revolution, and its effects and duration are conceived accordingly. As to its participants, Jouffroy seems to appeal to everyone, or at least everyone working within the arts, but he identifies a number of artists or artistic forms that exemplify the strike or tactics associated with it, all undertaken during 1968 or shortly before. These include the revolutionary posters of Atelier Populaire, Olivier Mosset’s abstract paintings, Erró’s American Interior series and Chris Marker’s ‘film-tracts’. Jouffroy complements the latter with his own suggestion of ‘book-tracts’.

Lozano’s General Strike Piece

In July 1969, the journal 0 TO 9 published a transcript of Lee Lozano’s General Strike Piece. It announced her commitment to:

Gradually but determinedly avoid being present at official or public ‘uptown’ functions or gatherings related to the ‘art world’ in order to pursue investigation of total personal & public revolution. Exhibit in public only pieces which further sharing of ideas & information related to total personal & public revolution.14

Lozano started the strike on 8 February 1969 with her withdrawal from an exhibition at the Goldowsky Gallery in New York City, and she compiles a list of the last time she attended uptown galleries, a museum, concert, film showing, ‘event’, big party and bar. She also records her withdrawal from the Art Workers’ Coalition, Artists Against the Expressway and unnamed other groups.

Lozano’s conception of the revolution to which the strike was committed is outlined in a statement she read out at an open meeting of the Art Workers’ Coalition, which also indicates why she withdrew from the group:

For me there can be no art revolution that is separate from a science revolution, a political revolution, an education revolution, a drug revolution, a sex revolution or a personal revolution. I cannot consider a program of museum reforms without equal attention to gallery reforms and art magazine reforms which would aim to eliminate stables of artists and writers. I will not call myself an art worker but rather an art dreamer and I will participate only in a total revolution simultaneously personal and public.15

The ‘pieces’ exhibited in pursuit of this revolution are also listed in a note to General Strike Piece, namely, Grass Piece, No-Grass Piece, Investment Piece, Cash Piece and one entitled simply Piece.

According to an amended handwritten version of General Strike Piece found in Lozano’s notebooks, from which the transcript in 0 TO 9 was taken, the strike ended in the autumn of 1969 due to what are described as ‘schiz symptoms [which] began to appear (me in here vs. them out there)’.

The 1970 Art Strike

On Friday 22 May 1970, an ‘Art Strike’ was announced in New York. It was the initiative of members of the Art Workers’ Coalition (principally, Poppy Johnson and Robert Morris).16 According to the leaflet publicising the strike and outlining its ends and means:

The artists of New York, along with many art writers, gallery owners and museum staff – in memorium [sic] to those slain in Orangeburg, S.C., Kent State, Jackson State and Augusta, as an expression of shame and outrage at our government’s policies of racism, war and repression – are asking all museums, galleries, art schools and institutions in New York to close in a general strike on this day, Friday, May 22, 1970.17

The leaflet goes on to outline a number of demands and resolutions. These revolve around the general suspension of museums’ and galleries’ normal activities in order to mobilise them in ideological, institutional and practical support for a campaign against racism, war and repression. The leaflet also demands that: artists and dealers contribute a percentage of their sales to a ‘rescue fund for resisters of war, repression and racism'; artist-representatives are included on museums’ policy-making bodies; and that ‘an “emergence cultural government” be formed to sever all collaboration with the Federal government with regard to artistic activities’. The strike does not call on artists to withdraw from the art world or from making art, although this may have been presupposed. The strike was to run for two weeks.

The strike appears to have been relatively effective in closing the institutions, at least for the first day of the strike, with the Metropolitan Museum of Art being one of the few to remain open. Its further effects are difficult to ascertain.

The strike was likely informed by an awareness of the Federal Art Project actions, albeit possibly more the notorious sit-ins, pickets and boycotts than the actual work stoppages, and perhaps the threatened strike by the Artists Tenants Association. Lozano’s strike was directed against, among other things, the Art Workers’ Coalition, and this antipathy distinguishes the two strikes markedly, but she was nonetheless personally close to Morris and so some influence or negative reaction might be adduced, however unlikely it appears. In any case, the direct precedents for the strike were rather two or three actions that were not presented as strikes as such. On 15 October 1969, the Art Workers’ Coalition organised a ‘Moratorium of Art to End the War in Vietnam’ in New York. The Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, the Jewish Museum and several commercial galleries closed for the day. The Metropolitan Museum and the Guggenheim Museum refused to close, although the Metropolitan did postpone its planned opening of a new exhibition on that day. The Guggenheim was picketed. To this precedent might be added the event occasioning the original formation of the Art Workers’ Coalition: on 3 January 1969, Takis physically removed his artwork, Tele-sculpture, from an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in protest at how it had been presented. Takis removed it to the Museum’s sculpture garden where he remained until securing confirmation that it would be withdrawn from the exhibition. More directly, on 15 May 1970, Robert Morris closed his solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum two weeks early, in protest at ‘the intensifying conditions of repression, war and racism in this country’.18

Monty Python Flying Circus’ ‘Art Gallery Strikes’

On 15 December 1970, the British Broadcasting Corporation screened ‘Art Gallery Strikes’, a comedy sketch by Monty Python Flying Circus.19 This imagines a strike, not by artists or gallery workers, but rather by figures within works of art.

The sketch begins in London’s National Gallery with a conversation between two connoisseurs enraptured by Titian’s painting of The Trinity. (Originally attributed to Titian, the picture is now considered a copy.) The connoisseurs’ conversation is interrupted by the entrance of a figure in traditional rural dress, who walks up to the painting and presses on the nipple of a prostrate figure in the foreground. The nipple turns out to be a door bell. In response, the figure of a cherub higher up in the painting is dislodged or withdrawn from the picture plane as if it were a cut-out, montaged in place, with the capacity to move itself at will. The transformation of this cut-out into human form takes place through the sound of footsteps descending stairs behind the painting and the opening of a concealed door from which the cherub, now played by an actor, then appears. The rural figure now identifies himself as from another painting, John Constable’s The Hay Wain, and asks to speak to the cherub’s father. Then follows an repetition of the cherub’s personification, this time by the figure of God. The rural figure informs ‘God’ that there has been a general walkout initiated by ‘The Impressionists’. All the ‘art historical schools’ resolve to strike, which is depicted by a sequence in which numerous figures in famous paintings withdraw themselves like the cherub, but now as an act of withdrawing their labour or striking. A subsequent scene depicts a Sotheby’s auction at which the prices of pictures are slashed due to their absent figures.

Given that the sketch was recorded on 25 June 1970, it is reasonable to suspect that it was written in response to reports of the art strike in New York in May of that year, perhaps struck by the suggestion that the strike concerns ‘art’, rather than ‘artists’.

Image: Monty Python Flying Circus, ‘Art Gallery Strikes’, BBC, 1970

Metzger’s ‘Years Without Art’

In 1974, Gustav Metzger called for ‘years without art’ in order to ‘bring down the art system’ and, thereby, its legitimation of the state. Appealing to the model of industrial strikes and their effectivity, he called on all artists to engage in a ‘total withdrawal of labour’ for a period of three years, 1977–1980, during which they should refuse to ‘produce work, sell work, permit work to go on exhibition, and refuse collaboration with any part of the publicity machinery of the art world’. Metzger calculated: ‘Three years is the minimum period required to cripple the system, whilst a longer period of time would create difficulties for artists.’ He added: ‘Some artists may find it difficult to restrain themselves from producing art. These artists will be invited to enter camps, where the making of art works is forbidden, and where any work produced is destroyed at regular intervals.’

Metzger’s call was published in the catalogue, Art Into Society/Society Into Art: Seven German Artists, accompanying the homonymous exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, which ran from 30 October to 24 November.20 This was his only contribution to the exhibition.

Metzger dutifully undertook the strike for the full three years, but no one joined him.

Đorđević’s International Strike of Artists

In 1980, papers related to an abandoned ‘International Strike of Artists’ were published in the Belgrade journal, Časopis Studenata Istorije Umetnosti [Art History Student Magazine], by Goran Đorđević.21

In February 1979, Đorđević had written to numerous artists calling for the strike ‘as a protest against [the] art system’s unbroken repression of the artist and the alienation from the results of his practice’. He stipulated that the strike should last ‘for a period of several months’, but left further details to be worked out once it was clear who wanted to participate and what proposals for tactics they might have. Of the 40 or so replies he received, the overwhelming majority declined, with a few exceptions. Consequently, Đorđević decided to abandon the strike, but also to publish the call and selected replies in the hope that they might prove instructive:

The idea of the international artists strike is under present circumstances probably an utopia. However, as the processes of institutionalization of art activities are being successfully applied even to the most radical art projects, there is a possibility that this idea could one day become an actual alternative. I therefore believe that publishing of the replies I received could be of certain interest.

Given that several of the artists with whom Đorđević corresponded were involved in the Art Workers’ Coalition, it seems likely that he took some inspiration from the 1970 art strike.

The 1990–3 Art Strike

In the summer of 1985, a flyer was reportedly distributed calling for an ‘art strike’ from 1990 to 1993.22 According to a subsequent flyer, which is undated but probably distributed in the spring of 1989, the strike called on ‘all cultural workers to put down their tools and cease to make, distribute, sell, exhibit, or discuss their work’ during this period. It also called on ‘all galleries, museums, agencies, “alternative” spaces, periodicals, theatres, art schools &c., to cease all operations’. The call is directed against marketing art as an ‘international commodity’, but also at the very definition of art by a ‘self-perpetuating elite’, that is, a ‘bourgeois art establishment’ able to marginalise or co-opt the work of even those ‘cultural workers who struggle against the reigning society’. The call goes on to narrow its focus on the very identity of the artist as a form of exclusion or elitism justifying ‘inequality, repression and famine’: ‘It is the roles derived from these identities, as much as the art products mined from reification, which we must reject.’ This is emphasised to the point of displacing struggles over production, in contrast to Metzger:

Unlike Gustav Metzger’s Art Strike of 1977–1980, our intention is not to destroy those institutions which might be perceived as having a negative effect on artistic production. Instead, we intend to question the role of the artist itself and its relation to the dynamics of power within capitalist society.

The initiative and principal organiser for the art strike seems to have been Stewart Home, although, unlike Metzger, he endeavoured to pursue it collectively, initially through a group called PRAXIS and subsequently through various attempts at dissemination that grew out of his involvement in Mail Art and the employment of pseudonyms he derived from Neoism. The art strike was propagated through a number of Festivals of Plagiarism held simultaneously in January 1988 in London, Madison Wisconsin and San Francisco, followed by further events in Braunschweig and Glasgow. The strike appeared in this context as a general ‘refusal of creativity’, which itself plagiarised Metzger’s strike. The idea of the strike was contested and ridiculed, but even some of its detractors embraced it as a valuable provocation. The San Francisco Festival led to the organisation of an Art Strike Mobilization Week at the ATA Gallery in early 1989, and the formation of an Art Strike Action Committee. Other such committees were founded in Baltimore, Ireland and London, and there is even mention of one in Uruguay. These activities were accompanied by numerous publications.23

Reportedly, only Home, Tony Lowes and John Berndt – the leading figures of, respectively, the London, Irish and Baltimore Art Strike Action Committees – actually undertook the strike and withdrew from all artistic activity during 1990–93.24 No museums, galleries or other institutions closed, although the journal Photostatic did cease publication in order to publish YAWN, a newsletter reporting on the strike and discussions around it.25 Home joked that ‘the psychological impact of the Art Strike was largely responsible for [the] cultural crisis’ attending the early 1990s crash in the art market.26 But he also openly admitted that the strike would not involve enough artists to close any galleries or institutions, and that its aims were rather propagandistic.27

The 1990-3 strike was accompanied by an unprecedented historical self-consciousness about art strikes. Besides the crucial precedent of Metzger’s strike, Home identifies Jouffroy’s call, the 1970 art strike in New York and Đorđević’s proposal, as well as cases during the so-called Martial law period in Poland and in 1989 in Prague.28

Image: Emblem for ‘The Years Without Art, 1990-3’, c. 1989

IPUT’s ‘General Art-strike’

In 1991, the International Parallel Union of Telecommunications called for a ‘general art-strike’ in May of that year. The call was published in YAWN, the newsletter for the 1990-3 Art Strike, to which it contributed, but to which it cannot be reduced insofar as it derived from an independent strike in the field of art dating back to the mid-1970s, if not before.29

The aim of the strike is declared emphatically and esoterically in the opening propositions of the call:

The Strike as such is an aesthetic-ethical operation on the deformed body of the reigning Myth.

The Strike – by definition – is declared on the territory between Genesis 15 to 24.

This obscure territory is the theo/logical link of the sweaty cause and deadly effect.

The call is signed off: ‘A ghost wanders the world, the ghost of the strike!’30 No details are offered on the means of the strike. The participants are requested to arrange it themselves and/or send proposals to the Union before the end of April. Appended to the call are the contact details of the three signatories: Michel Ritter, Chris Straetling and Tamás St. Auby.

The call for the strike is combined with the proposition of a model, ‘The Perpetuum Mobile’, a diagram of which is illustrated, followed by an amended version. Participants are also requested to arrange this themselves and/or send proposals. These diagrams are no less esoteric than the aims of the strike. The first version presents a set of terms arranged along the lines of three adjoining circles. The arrangement suggests relations of opposition, but also of complementarity, perhaps even identity. Thus, the first circle places ‘art’ on the left, ‘anti art’ (notably not hyphenated) on the top, then ‘art-strike’ (notably hyphenated) on the right and ‘un-art’ on the bottom. ‘Art-strike’ then adjoins to the left of the second circle, followed clockwise by ‘more art’, ‘art is strike’ and ‘bad art’. Finally, ‘art is strike’ adjoins the circle with ‘art is work’, ‘strike is art’ and ‘strike is work’. The second version reproduces the first, albeit with broken lines for the three circles, and adds two rows of four adjoining circles, each labelled ‘perpetuum mobile’, which envelop and traverse the first three circles, indicating alternative relations between the terms. For instance, ‘anti art’ becomes the left part of a circle with ‘more art’ on the right and ‘art-strike’ on the bottom, with the top left either empty or occupied with the pervasive ‘perpetuum mobile’.

There seems to be no record of participants or proposals for the strike or model.

Together with the 1990–3 strike, the call also acknowledges Metzger: ‘The Gustav Metzger-Stewart Home proposition enlightened the social implications of this relation: – the Art-Strike clearly defined its position on the Market of the Myth.’ The suggestion is, not ‘the Myth’ itself.

The precedents for the ‘general art-strike’ are indicated by the remark in the call text that the Union had been involved in ‘practicing different forms of Art-Strikes under the general title: 'The Subsistence Level Standard Project 1984W’. The Union was the initiative of one of the signatories of the call, Tamás St. Auby – also known by numerous pseudonyms. He founded the Union in 1968, in Hungary, nominating himself as its agent in various roles. The Subsistence Level Standard Project 1984W was initiated in 1974 or 1975, shortly before his exile from Hungary on accusations of smuggling samizdat literature out of the country. The basic aim of the Project was and remains to promote an alternative to work, which is approached as a profound economic, political and religious myth – the ‘reigning Myth’ alluded to in the call for a ‘general art-strike’. The refusal of this myth is embodied in the idea of striking, which hereby assumes a correspondingly profound status. The Project therefore promotes various forms of this striking, but also its consequences for an alternative life. Thus, its name derives partly from the contention that subsistence should replace the cycle of overconsumption and overproduction. One proposal to this end is the payment of a basic minimum income to artists from defence budgets. Beginning in 1980, the Project was developed in a series of stages. In the first, ‘The Mutant’, a new human is purportedly brought to life by the refusal to work. ‘The Mutant Class’ follows in the second stage. The third establishes their republic in a new canton of Switzerland. The fourth offers a ‘Catabasis Soteriologic’ or decent into salvation. The fifth phase, ‘Heterarchy’, facilitates direct democracy or voting on various subjects.31

St. Auby’s strikes might be traced back even further. In 1972, he undertook the action Sit Out. Be Forbidden! in which he sat on a chair on the pavement outside the Hotel Intercontinental in Budapest. He also produced a number of ‘action objects’ in this year, such as Prohibited To Switch On!, a readymade sign with these words, and St.Rike Bow, a violin bow with the strings cut. Still earlier, in 1965/6, his turn from poetry to practices associated with Fluxus is characterised, at least in retrospect, as ‘giving up art’.

The SPART Strike

Beginning in January 2009, the ‘SPART strike’ or ‘years without SPART’ called for a suspension of any participation in the artistic or cultural events programmed in Northern Ireland in support of the London Olympic Games in the summer of 2012. The strike was intended to confront the cuts and reallocations in state funding for the arts and culture during this period, which the British state justified as a means of funding and promoting the Games through a ‘cultural Olympiad’ that would employ numerous artists.

The strike was called by the SPART Action Group, principally, Justin McKeown, who had conceived of SPART in 2001 as ‘the ultimate hybridization of sport and art, and therefore the most evolved form of leisure on the planet’.32 The name was formed by compacting ‘sport’ and ‘art’. Its conception is condensed into a ‘dichotomy’: ‘SPART = the politicisation of leisure time[;] LIFE = my most profound leisure activity’.33 The plan of action for the strike recommended:

1. Turn protesting into a SPART leisure activity by giving as much consideration to the aesthetics of protest as we do to any other spartwork we might make.

2. Make protests more imaginative and exciting than the events of the Cultural Olympiad.

3. Create pockets of private clandestine cultural enjoyment in opposition to publicly enforced official cultural misery.34

The strike seems to have been announced first at an ‘Art Strike Conference’ held in 2008 in Alytus, where it was subsequently promoted at the Art Strike Biennial in the summer of 2009.35 It was also publicised in an article by McKeown in the journal for Visual Artists Ireland, which describes itself as ‘The Representative Body for Visual Artists in Ireland’.36 No record seems to exist of its participants or effects.

The description of the strike as ‘2009-2012: The Years Without SPART’ alludes to Metzger’s three-year strike, but this influence was probably mediated by knowledge of the 1990-3 Art Strike and, most directly, by the discussions in preparation for the Art Strike Biennial.

The Art Strike Biennial

During 18–24 August 2009, an art strike was declared by the coordinators (principally, Redas Diržys) of the alternative art biennial held in Alytus, southern Lithuania, since 2005, which transformed its third manifestation into an ‘Art Strike Biennial’. One of the headline aims of the strike was to oppose the nomination of Lithuania’s capital, Vilnius, as the European Union City of Culture for 2009, denouncing the whole EU programme as a process of cultural colonisation. The strike called on all concerned to refuse any participation in the events comprising the nomination. It added: ‘We are also calling for international support to assault the cultural capitals in whatever country it will appear in the future and later to continue the actions in the same place every second year – so to arrange an international network for debiennialization.’37 The strike also called for the organisation of events in Alytus as an alternative to those in Vilnius. These were not systematically recorded as a matter of principle: ‘No schedules to be provided – artists appear and disappear in the social space without any wish to document or visualize the shock-result of his intervention.’38 Nonetheless, numerous documents and images were published on the Biennial website. The strike call includes the notable proposal to construct a ‘Capital of Culture Destruction Machine’, which was to be based on Willhelm Reich’s Orgone research and Nikola Tesla’s perpetual motion theories. Another proposal was a version of Metzger’s art strike camp, which is described as a ‘ghetto for the artists who are not able to quit doing arts’, where art that would have contributed to the City of Culture programme would be used as ‘scrap-art-yard-capital’.

Calls for the strike date back to the preceding year. During 27–29 June 2008, an ‘Art Strike Conference’ was held in Alytus, which explored ideas for the strike broadly, not only against the nomination of Vilnius. Stewart Home contributed to the conference and, besides Metzger’s strike, the 1990-3 Art Strike was clearly the major influence on the Biennial, although the SPART strike also seems to have originated from this conference, and the precedent of other art strikes can probably be assumed. Diržys concludes his report on the conference, published later that year: ‘So, we are calling for Art Strike 2009 as a real pre/anti/post-cultural figuration! Join us in Alytus on August 18-24, 2009!’39 The official call for the strike was published on the Biennial website on 26 December 2008, signed by the ‘Second Temporary Art Strike Action Committee – Alytus Chapter’.40

The impact of the strike on Vilnius’ term as City of Culture is not recorded and was presumably negligible, but the Biennial was relatively well attended.

The art strike became something of a model or framework for subsequent Biennials in Alytus, but it was subsequently inflected by other themes. 2011 was dedicated to the ‘congress and outflows’ of a Union of Data Miners and Travailleurs Psychique. 2013 and 2015 were both nominated ‘Alytus Psychic Strike Biennial’. These were the last Biennials located in Alytus, followed by the so-called ‘Dissolution of Alytus Psychic Strike Biennial into Antimatter of Biennialization’, which included 3-Sided Football World Cups held in London (2016) , Kassel (2017) and Madrid (2018).

Aminde’s Strike: Opera

In 2011, Ulf Aminde restaged Joseph Haydn’s Abschiedsadagio [Farewell Adagio], written in 1772, under the title Streikorchester, playing on the pun with Streich [meaning stroke, but also prank], at the Heidelberger Kunstverein. This was the first of three iterations, collectively entitled Streik: Opera – the second staged at ‘Truth is Concrete 24/7’ in Graz, 2012, and the third at ‘Performative Democracy’ series at the Museum of Contemporary Art Leipzig, in 2013. Aminde proposed that Haydn’s Abschiedsadagio, dated 1772, presents the first art strike, which Streik: Opera sought to restage.

Haydn’s Abschiedsadagio is the fourth and final movement of his Symphony no. 45 in F-sharp minor, also known as the Abscheidssymphonie. It which was composed under the patronage of Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, at the end of an extended sojourn at the Prince’s summer palace in Esterháza, from which the court orchestra was eager to return home to Eisenstadt. During the final movement, each musician, on completing their part, snuffed out the candle on their music stand and departed from the stage, leaving just two muted violins by the end, originally played by Haydn himself and the concert master, Luigi Tomasini. The Prince appeared to concede the demand, returning the court to Eisenstadt the following day.

In the third iteration of Streik: Opera, Aminde invited various individuals to read texts related to the idea of an art strike, including Lozano’s General Strike Piece, with the intention that they would constitute something approaching a libretto. When Raimar Stange rose to speak, he just stood there silently, in what was gradually recognised as a kind of strike action, and which drew the whole performance to a halt as others refused to ‘interrupt’ him. Stange’s action reportedly derived from his objection to not being paid a fee and, presumably, his desire to stage an objection to the non-payment of fees in the cultural sphere more broadly. Stange was eventually interrupted by a musician from the Mendelssohn Kammerorchester Leipzig, who announced that she would leave shortly, at 9pm, since she was only being paid until then.41

The Polish ‘Day Without Art’

In May 2012, a one-day ‘art strike’ or ‘day without art’ was undertaken in Poland. The strike was organised by the Citizen Forum for Contemporary Arts (Obywatelskie Forum Sztuki Współczesnej) with the aim of improving the position of artists economically, politically and symbolically.42

A number of galleries and institutions expressed their solidarity with the strike. Some closed for the day. A press conference was held at the Zachęta National Art Gallery in Warsaw. The successes of the day were minimal.

But the strike proved to have repercussions. It publicised the plight of artists in Poland and consolidated the status of the Forum as the vehicle for a number of further struggles and actions. The Forum was formed in reaction to the use of funds from the Ministry of Culture to support spectacular events in 2012, such as the European Football Championship co-hosted by Poland and Ukraine, and the Polish Culture Congress, rather than to support artists and cultural workers more broadly. After the strike, the Forum formed a programme: to ensure artists received payment from art institutions, to include artists’ remuneration within the rules for grants from the Ministry of Culture, to include artists’ labour rights in employment legislation, to provide pension and health insurance for artists, and to publish a ‘Black Book for Artists in Poland’ that would define the status of artists and cultural producers. The Forum joined a new union, Workers’ Initiative, itself formed in 2004 to support new forms of employment and contracts not recognised by traditional unions. This resulted in a commission to support artists in securing fees. By 2014, an official agreement on minimum fees had been signed by the Art Museum, Łodz, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, the Zachęta and the Arsenał Gallery, Poznan, with pledges to sign by several other institutions.43

Image: Art Strike rally in front of the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, 2012. Photo by OFSW

Pledger’s Call for a National Artists’ Strike in Australia

In 2013, a National Artists’ Strike was called in Australia by David Pledger:

This is a call on all artists to undertake a rolling National Strike – a month-long retraction of the labour and goods of all artists including actors, dancers, musicians, choreographers, composers, designers, directors, sculptors, photographers, writers for theatre, film and television, media artists, digital artists, painters, sound artists.

All such artists in workplaces benefiting in any part from government subsidy, be it local, state or federal, are encouraged to cease work one day a week for the duration. Any artist whose work is performed or exhibited during this time is encouraged to withdraw that work for the duration.44

The strike was called to secure four demands: the replacement of unemployment benefit with a living wage for artists during periods of unemployment; the formation of an Artists’ Commission Pool funded by a voluntary 5 percent salary sacrifice by staff of government arts and cultural agencies; 50 percent representation of professional artists on all assessment, consultative and governance panels; and, for performing arts, the distribution of production funds directly to artists and the reallocation of infrastructure grants for five years into artists’ fellowships to develop projects.

The call did not say when the strike would start. And, in fact, it did not take place – at least, not to date. Pledger subsequently characterised the call as a provocation, which he hoped would ‘take hold in people’s imaginations’.45

Mason’s Untitled (Art Strike)

In 2014, Adam Paul Mason posted on a website presenting his artistic practice a ‘public notice’ with two suggested titles: Untitled (Everywhere…Nowhere) and Untitled (Art Strike):

Baring that action can be translated into a state of quantifiable physical equivalence no new work shall be tangibly produced beginning upon the date of 9/08/2014. The duration of this specified construct shall last for a minimum period of one year and culminate upon the date of 9/08/2015 or later. This hereby serves as outstanding final notice.46

No further information is offered that might indicate the aims or results of the strike, except that it lasted 369 days.

The Art Strike at the Project Space of Organ Kritischer Kunst

In 2015, an art strike was called by the co-ordinators of the alternative art institute, Organ Kritischer Kunst/Organ of Critical Arts, at its project space, OKK/Raum29, in Wedding, Berlin. The call was published on the Organ’s website in January, when the strike seems to have begun, and publicised in some press reports, which included interviews with the principal organiser of the strike, Pablo Hermann.47

The strike was directed at the precarious economic conditions of artists engaged in critical projects, like those promoted by the Organ. The call announced a suspension of labour at the journal and project space, but also called on all artists to participate. The strike was therefore not aimed at the Organ Kritischer Kunst itself or a faction within it, but rather the broader social conditions under which its projects were forced to operate. More specifically, it was directed at the refusal of the German State to recognise artists’ fundamental rights. Hermann cited the refusal of the Künstlersozialkasse [Social Security Benefits Office] to recognise his work as proper artistic work, resulting in his disqualification for health insurance support.48 The call concludes:

If fundamental rights are not even guaranteed and also so many bureaucratic hurdles are put in the way, then any attempt to achieve a minimum of dignity for one’s work by maximizing self-exploitation will become obsolete – therefore, definitely: strike!

The strike is also proposed as an alternative to other initiatives to redress the precarious condition of artists in Berlin, and refers to the self-serving cynicism of artists sponsored by George Soros’ programme for ‘Open Society’, which it associates with capitalism and racism. A poster for the strike announces the demand: ‘no more artwork for white supremacy culture’.

No duration is specified for the strike. The call claims the strike is ongoing, and no formal statement of its cessation was made. However, work in the project space had recommenced by June.

The strike appears to have taken some inspiration from the Art Strike Biennial. The call was published in January 2015 within the framework of the Alytus Psychic Strike Biennial, and the poster is signed ‘Dead Workers Union, Wedding branch’ – the Union being an initiative of the Biennial.49

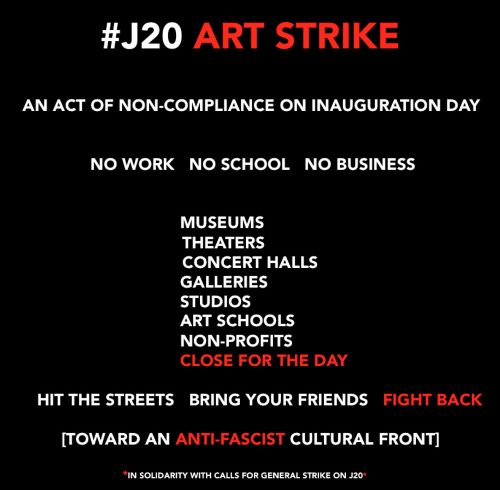

The J20 Art Strike

An art strike was called for Friday 20 January 2017 in response to the inauguration on that day of Donald Trump as President of the United States. The call was publicised through a dedicated website and covered widely in the press.50

The call reads:

#J20 Art Strike

An Act of Noncompliance on Inauguration Day.

No Work, No School, No Business.

Museums. Galleries. Theaters. Concert Halls. Studios.

Nonprofits. Art Schools.

Close For The Day

Hit The Streets. Bring Your Friends. Fight Back.51

A poster for the call signs off: ‘Toward an Anti-Fascist Cultural Front.’ According to an open letter signed by notable artists and critics, the strike concerned ‘more than the art field’, and was called ‘in solidarity with the nation-wide demand that on January 20 and beyond, business should not proceed as usual in any realm’. The poster also declares solidarity with ‘calls for a General Strike on J20’, and the letter refers to the Women's March in Washington, DC and other cities on 21 January. The website for the strike adds solidarity with the Women Strike, #DisruptJ20, Ungovernable 2017 and Disability March.52

A Declaration for the strike, entitled ‘Ungovernable/Anti-Fascist’, directed the strike less at Trump than ‘Trumpism – a toxic mixture of white supremacy, misogyny, xenophobia, Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, homophobia, ableism, militarism, kleptocracy, and oligarchic rule that bears a strong resemblance to Fascism’.53 It goes on to declare: ‘J20 is the inauguration of [a] new phase of resistance at a massive scale.’ On the contribution of art: ‘Committed to invention and critique, arts of all kinds are essential to any long-term political mobilization.’ It describes the art world as a contradictory field, ‘torn between the radical possibilities of art and the constraining limits of institutions, while looming over both are the machinations of neoliberal oligarchs’; contradictions which ‘[t]he Trump regime brings […] to a head’. Despite these contradictions, the art world is described as having ‘significant amounts of capital – material, social, and cultural – at its disposal’, which can be mobilised ‘in solidarity with broader social movements leading the way in the fight against Trumpism’. The open letter, which selectively draws on this declaration, adds that the art strike is ‘not a strike against art, theater, or any other cultural form’, but rather ‘an invitation to motivate these activities anew, to reimagine these spaces as places where resistant forms of thinking, seeing, feeling, and acting can be produced’. The Declaration recommends a number of actions: ‘Hold Institutions Accountable to Their Own Public Mission’, ‘Work to Dismantle Systems of Oppression Within Art Institutions’, ‘Name, Shame, and Divest from Trumpists and Other Oligarchs in the Art World’, ‘Connect to the New Sanctuary Movement’, ‘Stand With Our Colleagues Beyond Metropolitan Centers’ and ‘Collectivize Resources and Spaces in Support of Anti-Fascist Work.’54

Over 70 institutions and organisations are recorded as closing for the day or responding in other ways, such as waiving entrance fees.55

The J20 Art Strike does not specify any precedents from the history of art strikes, but it does reproduce a muted background image of the 1970 Art Strike in the Declaration, in which protestors are visible sitting on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art with placards reading ‘Art Strike Against Racism War Repression’.

Image: J20 Art Strike call, 2017

The Women Artists’ Strike

In 2019, a women artists’ strike was called by a group named CindyCat in protest against the sexist conditions of artistic and cultural labour, especially its economic precariousness. Its racism is also attacked. While principally addressed to women artists, its call for a ‘Künstlerinnen*streik’ also indicated with its asterisk an appeal to all genders oppressed by patriarchy.56 The strike was called in the context of the International Women’s Strike on 8 March that year, and publicised on the website for organisers of this in Germany.57 It was also posted on the website of the self-professed anarcho-syndicalist ‘Freie Arbeiterinnen und Arbeiter Union’ [Free Workers Union] (FAU), the Dresden branch of which CindyCat were affiliated.58

CindyCat introduces itself in the call text as a collective of six women artists and cultural producers, all in the precarious condition of earning little or nothing from their artistic or cultural labour, and nothing from their domestic labour, resulting in their need to take on additional wage labour. They hereby face not only the exploitation of unpaid domestic and care work, or the so-called ‘double shift’ of supplementary jobs, but rather a ‘triple shift’. And yet, the exploitation of this additional shift shares the same ideology as that surrounding domestic and care work: that ‘we do this work so gladly that payment is not at all necessary’; that ‘unpaid, emotional work seems to have been laid in the cradle of our socialisation as women as well as artists’. The call is entitled ‘No more devotion!’ It lists not so much a set of demands than resolutions of refusal: ‘We no longer accept that…’ Amongst these are, that:

– our work in the form of constantly new projects and never-ending application procedures is subject to repeated devaluation.

– being an artist is a matter of class […]

– our colleagues of colour have to confront again and again racist structures that also run through the culture business.

– feminist themes and concerns are appropriated thematically by large exhibition halls, yet nothing is changed in the structures or relations of production. […]

– women artists of all kinds in Germany earn an average of 30% less than their male colleagues.

– we have to peddle not only our work, but also our life, our personality and our passion in order to be counted a ‘real’ artist. […]

– the myth of the ‘artist-genius’, even in 2019, still legitimises everyday sexism in our industry.

These refusals infuse the subsequent characterisation of the strike:

We are on strike!

We are on strike against the history of the self-reliance of freelance work and no longer deliver ourselves solitarily to the industry.

We will confront the problems and the precariousness together and in solidarity.

We create awareness amongst those who enjoy art and culture, often without knowing anything of the conditions under which it is made.

We ensure transparency by talking to our female colleagues about specific conditions, payment, precariousness and poverty.

We are working towards a division of time that allows everyone to be creative.

We strive for an art that can be disturbing, that asks questions, that is complex and that does not obligatorily serve the entertainment, distraction and spiritual reproduction of exhausted, drained subjects.

CindyCat was formed in January 2016, inspired by a conference on the themes of strikes and labour in art, entitled ‘Streik/Arbeit’, at the School of Visual Arts in Dresden. This offered a rich history of art strikes, but there is no obvious influence on their strike. CindyCat then began to organise around these themes, especially with a view to collective action and unionisation around precarious labour in the arts, which they pursued in conjunction with the FAU, effectively constituting its ‘Branch on Art and Culture’.59 Their activities included the development of a questionnaire, ‘Should I do it for free?’60

The call text is more of an announcement of a strike by CindyCat, rather than a call for wider participation, although that is perhaps implied. No beginning, duration or end to the strike is specified. 8 March is clearly an emblematic date, and CindyCat participated, taking part in a ‘strike breakfast’ at the School of Visual Arts in Dresden, where they shared the results of their surveys on working conditions in the arts and organised a discussion amongst students. But their strike cannot be limited to this day, since it is announced as already underway and is proposed as continuing indefinitely.61

Image: CindyCat, ‘No More Devotion!’, 2019

The Hong Kong Artists Union’s Strike

On 12 June 2019, a strike was undertaken at numerous cultural institutions in Hong Kong in solidarity with mass strikes and protests against the government’s Fugitive Offenders bill, which would legalise their extradition to China. The bill was scheduled for its second reading at the Legislative Council that day. The strike was called by the Hong Kong Artists Union, and publicised through an open letter circulated the day before, in which the impact of the bill on art is described as follows:

The tabled bill, if passed, risk[s] seriously eroding the freedom of expression on which the work of artists and cultural workers of all disciplines depend. It also undermines the city's reputation and credibility as an international art hub where ideas flow freely.62

The letter requested that institutions suspend operations on the day and that they facilitate their employees’ participation in the strike, should they so choose.

These protests were preceded by a mass protest against the bill on 9 June, in which it is estimated one million took to the streets. On 12 June, 40,000 are estimated to have protested outside government headquarters, besides several other protests throughout the city.

According to one report on the Artists Union strike: the Asia Art Archive and Para Site officially joined the strike, the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts announced that the JC Contemporary gallery would operate with limited capacity, the Hong Kong Arts Centre remained open but welcomed protestors in need of water or first aid, and several commercial galleries closed for the day, including Ben Brown Fine Arts, Simon Lee, Lehmann Maupin, Gallery Exit, Puerto Roja, Karin Weber Gallery and Galerie Ora-Ora.63 The strike was also observed abroad with the closure of the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale for the day. Hong Kong-based artist, Trevor Yeung, covered his exhibit at the Liste Art Fair in Basel, Red Brighter, with a white cloth on which was written: ‘Artist decides not to show his work in order to protest Hong Kong-China extradition bill.’

After a sustained period of mass protests, the bill was eventually withdrawn on 4 September 2019.

The Art Strikes for Climate Strikes

On Friday 20 September 2019, an ‘art strike’ was undertaken by several museums in England and Wales in support of the ‘global climate strike’ that day.

The climate strike was called in anticipation of the United Nations Climate Summit on 23 September. According to the website for the strike, 7.6 million participated a week of actions, 20–27 September.64 An inspiration for the strike and its occasion on Fridays, was the ‘School Strike for Climate’ initiated by the Swedish school student, Greta Thunberg. In August 2018, Thunberg began sitting outside the Swedish parliament building every day during school hours with a homonymous placard, in protest at the government’s failure to reduce carbon emissions according to the UN Paris Agreement. On Friday 7 September, just before the Swedish general election, she announced that she would continue to strike every Friday until the Paris Agreement was implemented, coining the slogan ‘Fridays for Future’.

The art strike consisted of removing a popular artwork from public display for the day. This was often done through covering or shrouding it, rather than physically removing it. A notice of the strike was typically installed, sometimes with the slogan: ‘You don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.’65 The strike was publicised by activists on social media, principally, Ben Templeton, the participating institutions and the organisation MuseumNext.66 Museums in Bangor, Bath, Derby and Manchester participated. In Woking Town Hall, Sean Henry’s sculpture was covered. Despite its name, the art strike did not only appeal to museums of art. The Manchester Museum covered their fossilised skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex, tweeting: ‘Today Stan our T. rex is ON STRIKE, removed from public view & cloaked in black in solidarity with the #GlobalClimateStrike.’67 Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs shrouded the park’s figure of a Giant Deer.

The art strike was inspired by Bristol Museum & Art Gallery’s action in August in support of climate campaigns, notably Extinction Rebellion, in which it shrouded exhibits of extinct or endangered species in its natural history collection.68

On Friday 29 November, the art strike was restaged on the occasion of another global climate strike. This was promoted notably by the Viennese initiative #MuseumsForFuture, although it also promoted other kinds of action.69 Museums in Austria, England, Germany, Holland and Italy – not all museums of art – withdrew an exhibit for the day. The Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden covered Lucas van Leyden’s triptych, The Last Judgement.

Image: Lucas van Leyden’s triptych, The Last Judgement (1526 or 1527) in the Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, shrouded with notice reading ‘#Art Strike for Climate’, 2019

Stewart Martin is an Editor of Radical Philosophy and Reader in Philosophy and Fine Art at Middlesex University <s.c.martin AT mdx.ac.uk>

Info

The author and editors of Mute encourage anyone with information on omissions or additions to this inventory to get in touch.

Notes

1 One of the most extensive to date is the compilation of materials prepared by Ariane Daoust in relation to a project at the Centre des arts actuels Skol, Montreal, Grève de l’art? (2016), available at:

http://skol.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Grève-de-lart__livret.pdf

2 These demands are reproduced in detail, supposedly from minutes of the meeting, in Max Eastman’s account of the strike, ‘Greenwich Village Revolts’, in his autobiography, Enjoyment of Living, Harper & Brothers, 1948, pp. 548–59. This is the main source for the details described below. The seminal account of the strike is in Rebecca Zurier, Art for The Masses: A Radical Magazine and Its Graphics, 1911–1917, Temple University Press, 1988.

3 The WPA’s name was amended in 1939 to Work Projects Administration.

4 The Historical Records Survey, initially part of the Federal Writers’ Project, was subsequently established as an independent project.

5Art Front, November 1935.

6 This hunger strike is recorded in Jerre Manigone, The Dream and the Deal: The Federal Writers' Project, 1935-1943, Syracuse University Press, 1996, p. 167.

7 Gerald M. Munroe, ‘Artists As Militant Trade Union Workers During The Great Depression’ in Archives of American Art Journal, vol. 14, no. 1 (1974), (pp. 7–10) p. 8.

8 Estimates vary; this comes from Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century, Verso, 1997, p. 407.

9 ‘Disney strike is still on!’

10 The details of this strike have been drawn mainly from Aaron Shkuda, The Lofts of SoHo: Gentrification, Art, and Industry in New York, 1950–1980, University of Chicago Press, 95–100.

11 Available from the Archives of American Art at:

12 See Reinhardt’s homage to the Artist Tenants Association strike, or threat thereof, in his ‘The Next Revolution in Art (Art-as-Art Dogma, Part II)’, first published in Art News, February 1964, and reproduced in Barbara Rose ed., Art-as-Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt, University of California Press, 1991, pp. 59–62. The relation of the strike to Reinhardt’s sketch is discussed in Sarah K. Rich, ‘Ad Locum: Reinhardt’s Negative Politics of Place’, The Brooklyn Rail, Special issue on Ad Reinhardt Centennial, 2014.

13 Alain Jouffroy, ‘What’s to be done about Art? From the Abolition of Art to Revolutionary Individualism’ (1968) in Art and Confrontation: France and the Arts in an Age of Change, trans. Nigel Foxell, Studio Vista, London, 1970, (pp. 175–201) p. 181.

14 See Vito Acconci and Bernadette Mayer eds., 0 TO 9: The Complete Magazine, 1967–1969, Ugly Duckling Press, 2006. Original text capitalised.

15 ‘Statement for Open Public Hearing, Art Workers[’] Coalition’, from Lozano’s notebooks, dated 10 April 1969. Original text capitalised.

16 There are some indications the group went by the name ‘Art Strike’ and ‘New York Artists’ Strike’, which incorporated, besides the Art Workers’ Coalition, the Art Students’ Coalition, Women Artists in Revolution, United Black and Puerto Rican Artists and the Artists and Writers Protest Group. See the press release for their intervention at the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Museums, 1 June 1970, available from the American Archives of America at:

17 Available from the Archives of American Art at:

18 Quoted in Julia Bryan-Wilson, ‘Robert Morris’s Art Strike’, in Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era, University of California Press, 2009, p. 113.

19 ‘Art Gallery Strikes’, Monty Python Flying Circus. Part of episode called ‘Spam’ [episode 12 of series 2, or episode 25], recorded 25.6.70, broadcast 15.12.70.

20Art Into Society/Society Into Art: Seven German Artists, Institute of Contemporary Art, London, 1974, p. 79.

21 Facsimiles of Đorđević’s text in the journal together with correspondence on the proposal are reproduced in Ariane Daoust, Grève de l’art?

http://skol.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Grève-de-lart__livret.pdf

22 Stewart Home, ‘About the Art Strike’, in Stewart Home and James Mannox eds., The Art Strike Papers, AK Press, 1991, p. 3. Also available at: https://www.stewarthomesociety.org/artstrik.htm

23 Besides The Art Strike Papers, as above, see Stewart Home ed., Art Strike Handbook, Sabotage Editions, 1989; and the newsletter, YAWN, which published documents and discussions related to the strike over the course of its duration, 46 issues in total, from September 1989 to April 1993. Available at: http://yawn.detritus.net/

24 According to James Mannox, Introduction [Summer 1991] to The Art Strike Papers.

25 Details above.

26 Home, ‘Assessing the Art Strike’ (Notes for lecture at Victoria and Albert Museum 30 January 1993, available at:

27 Home, ‘About the Art Strike’, in The Art Strike Papers, p. 3

28 See ‘The Precedents’ in Home, ‘About the Art Strike’, pp. 1–2. I have not been able to establish whether these last two cases were explicitly presented as art strikes.

29 See YAWN no. 45, 15 August 1992. The call is also reproduced in ‘Mutants and Maffidiots: An E-mail Interview with Tamás St. Auby, the Vice-dispatcher of IPUT’, in the Budapest art magazine, Nightwatch, available at:

http://old.sztaki.hu/providers/nightwatch/szocpol/index.eng.html

On the pre-history of the call, see below.

30 This line is not included in the version of the call published in Nightwatch.

31 For details of the above and below see the records of activities by St. Auby/St.Turba prepared by the Bratislava art institute, amt_project, available at:

http://amtproject.sk/artist/tamas-st-turba

See also St. Auby website http://www.c3.hu/~iput/

32 Justin McKeown, ‘Play is Older than Culture’, in VAN [The Visual Artists’ News Sheet], July 2009. https://visualartists.ie/articles/van09-play-is-ol...

33 See ‘SPART or SPART ACTION’ in documents from the Art Strike Biennial, available at: https://antisystemic.org/alytus3/3.alytusbiennial....

34 ‘Spart Strike Northern Ireland’

35 Documents relating to the Art Strike Conference are available at:

36 See McKeown, ‘Play is Older than Culture’.

37 Redas Diržys, ‘About Alytus Art Strike Activity’. Available at:

38 Diržys, ‘About Alytus Art Strike Activity’.

39 Redas Diržys, ‘Art Strike Ideas and Their Application Today: A Report on the Art Strike Conference’ in Chto Delat? [What is to be done?], Special issue: When Artists Struggle Together. Available at: http://chtodelat.org/b8-newspapers/12-50/art-strik...

40 Namely, the aforementioned Diržys, ‘About Alytus Art Strike Activity’.

41 Details taken from Agnieszka Gratza, ‘Strike: Opera #3’, Frieze News, 27 January 2014: https://frieze.com/article/strike-opera-3

42 For details of the strike, to which the following is indebted, see Joanna Figiel, ‘On the Citizen Forum for Contemporary Arts’ in ArtLeaks Gazette 2, June 2014, 27–32. Available at:

43 ‘The minimum payments were set at 800PLN for taking part in a group exhibition, 1200PLN for taking part in a small group exhibition or so-called ‘project room’, and 3700PLN for a solo show (respectively c. 200, 300, 900Euro).’ Figiel, ‘On the Citizen Forum for Contemporary Arts’, p. 32.

44 David Pledger, ‘Call for national artists’ strike’, Temporary Art Review, 30 June 2014. http://temporaryartreview.com/call-for-national-ar... This is a republication of the call, first published in ArtsHub: https://www.artshub.com.au/news-article/features/a...

45 ‘Meet the artist who rallied creatives to strike for fair pay’: Interview of David Pledger by Briony Wright, in i-D, 24 May 2016. Available at: https://i-d.vice.com/en_au/article/a3v8qg/meet-the...

47 The call, poster and some contextual comments are posted on a project page, ‘Art Strike’, on the Organ Kritischer Kunst website: http://www.kritische-kunst.org/aso-art-strike-office/

See Peter Nowak, ‚Der Streik des 21. Jahrhunderts‘, Jungle.World, 13 May 2015, available at: https://jungle.world/artikel/2015/20/51947.html; and the interview ‘Arbeitskampf, nicht Kunst', in Neues Deutschland available at: https://www.neues-deutschland.de/artikel/969698.ar...

48 Hermann does not specify the grounds of his disqualification, but the minimum annual income required to qualify for social security benefits is 3,900 Euros. See https://www.kuenstlersozialkasse.de/kuenstler-und-...

49 See https://www.alytusbiennial.com/alytus-psychic-stri...šsivalymas-5.html

50 For press coverage see the ‘J20 Art Strike’ website:

51 See call and open letter: the https://www.j20artstrike.org

54 See Declaration for details on each action.

56 The asterisk or ‘gender star’ emerged recently as an alternative to using a slash, in order to indicate non-binary genders. But note that CindyCat’s positioning of the asterisk is unconventional – normally, it would be positioned after the male form (as in ‘Künstler*innenstreik’), whereas ‘Künstlerinnen*streik’ removes the male form, or at least displaces it from the leading position.

57https://frauenstreik.org/aufruf-zum-kuenstlerinnenstreik/ Note that CindyCat’s deployment of the gender star is ignored in its transcription here.

59 For details of CindyCat’s formation and activities see https://dd.fau.org/branchen/kunst-kultur/

60 This is available to be undertaken at: https://cindycat.net

61 The strike call remains on frauenstreik.org in the context of events for 8 March 2020, but this is just a hangover from the previous year.

62 ‘An open letter to the cultural institutions of Hong Kong, re: the Hong Kong Artists Union’s call-for-strike’

63 Chloe Chu and Ysabelle Cheung, ‘Hong Kong Artists Join Mass Protests Against Extradition Bill’ in ArtAsiaPacific, 13 June 2019.

65 Signage and other materials for museums to deploy in the strike were made available in a ‘toolkit’:

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com