The Art / Canape Nexus

When theorists subject art to matrices of value - economic or sociological - we don't necessarily arrive any closer to a 'law of art value', but what we do get is an uncomfortable insight into art/criticism's crisis of worth within an exploitative and celebrity-driven culture industry. Esther Leslie considers Isabelle Graw and Diedrich Diederichsen's recent offerings

Two German books on art translated into English and published by Sternberg Press promise to divulge the secrets of that most mysterious thing: the artwork. One is by Isabelle Graw, Professor for Art Theory and Art History at the Frankfurt Städelschule and founding editor of the journal Texte zur Kunst. The other book is by Diedrich Diederichsen, a pop journalist and lecturer at the art school in Vienna. Their appearance in the same slice of time might be one reason to ‘compare and contrast'. Their commonality of interest - art's value (in all its resonances), art as a ‘special kind of commodity' - is, in both, parsed through the still glowing, then extinguishing, embers of Marx's and Marxists' thoughts. For who else could be shaken out for the umpteenth time in relation to the topic of value in artistic production and consumption? But the feel, the look, the mode of each is quite different.

Graw's book is big and flimsy (intellectually), translated most invisibly by Nicholas Grindle into excellent English. Diederichsen's by contrast is thin and dense - and in three languages (English/German/Dutch). Graw's exposes herself and her chums as energetic players in the artworld and its formation of values, aesthetic, monetary and symbolic. Diederichsen plays his cards close to his chest - he is an observer of things. Graw's argument is diffuse and follows many threads. Diederichsen holds to a single line of argument. Graw's is full of names, while Diederichsen names no-one. But both share the aim of speaking to the current interest in art and politics, though neither out of any particular sympathy with the artist as activist. Both want to understand that curious fact, that the magic touch of art commutes something into something of great value. This transvaluation, however, occurs only if a whole set of factors are mobilised on the side of the artwork, or more specifically on the side of the artist - the dealers, galleries and critics. In Graw's case in particular, she is acutely aware of her own role in this value-making process: the critic as marketer, advertiser, booster of art value is one that she knows she has played. And she has been rewarded for that, financially and also, as she admits, personally, recompensed in canapés and wines and glamorous photo shoots of the Frankfurt Art World in slick magazines.

Image: Malevich's Suprematisme, 1920-27, after Alexander Brener's performance-art vandalisation in 1997

Graw's main thesis is that the artist is now a celebrity (there is no representation in her book of the likelier profile of the artist, who, according to a more or less arbitrary law of success, is a virtual nobody reliant on handouts: for this see Greg Sholette's ‘Dark Matter' thesis). To be an artist, for Graw, is to be a celebrity. To be a celebrity is to be a commodity. That is not so bad a fate, according to Graw, for she is keen to distance herself from the local philosophical dialect of Adornoism with all its cultural pessimism and market antipathy. Still, there is enough regional Ebbelwei - Frankfurt's sour and heady apple wine - in her to be snippy about brands and fashion. She works with the assumption that while, empirically, the market and art are fused, the desirability (however unlikely) of their separation is to be advocated. She marks out an autonomous space for art as opposed to media culture, but autonomy collapses back into dependence as she shows how the artworld is a microcosm of the larger world, in which there is no longer any separation of work and life, in which the self is a production, always on show, in which everyone is always performing, self-grooming his or her image, as part of a life work. Artists, like anyone else, constantly monitor their personal aesthetic. They market their own ‘personality' to the point of self-exploitation (not here, note, a Marxist category, nor a very meaningful one).

Graw's artists are cynical or amenable (depending on your vocabulary). They are players of a market, connoisseurs of its fads. Graw identifies Georg Baselitz and Andreas Gursky as artists who have made clear (and are not embarrassed to make clear) that their choice of motive and the form of their pictures is influenced by what sells. There is no surprise there, and certainly nothing epochal in this. Surely it has been true since, at least, the days of 17th century Dutch painting, executed on those lovely flat canvases with their charming homely motifs, all so perfect for hanging on a merchant's interior wall and shippable like any other commodity. As Graw notes, in the very mobilisation of art by the market lies the conditions for its partial autonomy, its leading of life in its own shifting terms rather than within the strictures of form dictated by craft production. Yet, it must be true that there is something new in the contemporary, as Graw's analysis would suggest, now the production, marketing, distribution etc. of art is globally organised and efficiently executed, based on the model of the film and media industries. Galleries and supercollectors sing and the rest of the art world dances.

That is the depressing but hardly shattering message of the book. Perhaps its most interesting aspect is the way it positions the critic - that is to say, the way it reflects on the author's own engagement in the processes described. The critic is marshalled into this market of art and marketing of the self. The critic's choice of art to write about is influenced by market success. It is also, she admits, influenced by what others have talked up around the restaurant tables of post-opening meals. Artists produce visuality, or events, or some sort of substance or immaterial ether that can be labelled art (by an artist), and is ratified by a gallery. Critics produce meaning. In one of the more (contortedly Bourdieuian) theoretical points, Graw argues that ‘market value' can only exist on the basis of ‘symbolic value' - by which she means art's interpretation, or the buzz around it. Art is talked up by critics. It amasses symbolic value. This translates into cash value in the market. Or at least, she argues this at some points. At others, the market alone is the arbiter of value, now that cultural capital, the caché that accrues to art precisely through its aloof separation from the market, no longer holds. This may not be such a contradiction, if the critics who produce symbolic value are seen to have been absorbed into the market and its emanations of the culture industry (magazines with best-of lists, TV programmes) - as opposed to some supposedly purer, higher realm of aesthetic discussion. Such thinking is not unlike the insights of Adorno from back in 1949: just before he returned from his exile home in the USA to Germany, Adorno wrote an essay titled ‘Cultural Criticism and Society'. Here he discussed criticism as something that had effectively disappeared, had become advertising or propaganda. Cultural criticism had become, he insists, a form of ideology brokering. Perhaps Graw is half-Adornian. She might agree thus far, for she argues as much here and there in the book. But that art can or should exemplify a realm of freedom or propose a relationship to truth is a hope too far in a Grawian world of microuniverses where there are no longer universal validities.

Graw proffers a solution. There is no way out of the market. Adorno's hallowed realm of autonomy is largely extinct. Therefore, she champions such art which thematises its own inextricable entanglement in the market. ‘Market-reflexive' is the name Graw chooses for the ‘line'. Warhol perfected it (replete with the apparently required faux-naivety). Courbet had a sniff at it earlier. Yves Klein, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons have all developed this play between art and market, which is both canny and dumb. Andrea Fraser flies the flag nowadays - most notably when she fucked a collector and videoed it for posterity, or for the artworld (because this is not a video that turns up on an anarchically accessible site such as YouTube). Market-reflexivity leaves the supply apparatus of art untouched. It is not clear if Graw is disturbed by this or not (such that one German reviewer has written of two authors of the book - Graw 1 and 2). The book is pervaded by ambivalence (or peppered with non-sequiturs): we do it, but maybe we shouldn't, but if we do it and know we are doing it and show we are doing it and show we know we are doing it, but not cynically, then maybe that makes it interesting or alright or something and it services both our horror and our fascination and we get paid and get to go to parties and photoshoots and it gives us something to write a book about.

Image: critic and Texte zur Kunst editor Isabelle Graw with collector Paul Maenz, Berlin 2009

The title ‘High Price' captures something about the book's ambivalence. High price is a statement of fact. Some art costs a lot. Of course there is also the phrase ‘a high price to pay', which is to say, it is always too much, or something else is lost in the transaction, which makes it not worth it. In German too there is a pun in the title. Der hohe Preis means both high price and high prize or award. Art is the prize. It is the ultimate thing, after necessity, in touch with freedom, such a great investment, and yet, like any fetish, tinged with the magical. Diedrich Diederichsen's book, On (Surplus) Value in Art, also sets out from a linguistic play. The notion of ‘Mehrwert' has its everyday meaning - ‘the pay off', a bonus, an added extra. In art this might intimate something about how the toilet bowl has one value as bathroom object, and quite another once entered into the Armory Show and titled ‘Fountain'. Quite simply, art has added to value, by being art. Art is this ‘pay off', this speciality that is the bonus, the good, ‘good for something', even if that goodness is to do with its being good for nothing, or use-less. Since Duchamp, Diederichsen tells us, this good has consisted more and more in delivering a punch line, the twist, the thing that is crazy beyond funny and so gives art purpose - a final line, a last word. (This is not to deny, he states, the continued existence of those who want art to be utterly auratic, immersive, otherworldy). In whatever form, art has an ‘exceptional status' in bourgeois society, for it has its own rules, is ‘regarded as an ally of desire' and ‘accepted as one of those forces that refuse to fall in line with the imposed, coerced consistency of life.' In addition, ‘it is also demanded of art that it, unlike the rest of life, be particularly full of meaning.'

'Mehrwert' also has its technical economic meaning: surplus value, which is also called ‘gross generic profit' and is quite precisely the differential between the value of capital at the point of investment in production (wages, wear and tear of machinery etc.) and the value of the yield at the end of the cycle. The profit, in short, whose source, according to Marx, is the gap between what workers receive for their labour power and time, in order to reproduce themselves, and what the capitalist is able to realise from the output value of the totality of the workers' exertions. In relation to this, Diederichsen examines what type of commodity art is. Like any other commodity its price can be calibrated as a ‘reasonable' sum like any other commodity on the market - an average of the socially necessary labour time used up in creating all artworks. To make the figure somewhat more plausible Diederichsen adds in the years of training at art school, such that the averaged price paid for an individual hour of labour drops considerably. Diederichsen takes Marx's terminology further in his quest to discover the source of art's price and value

Now, if we view artists as entrepreneurs who are acting in their own material interest, then the knowledge they have gained in bars and at art school would be their constant capital and their seasonal production in any given year would be their variable capital. They create Mehrwert to the extent that, as employed cultural workers, they are able to take unpaid time and often informal extra knowledge away from other daily activities - some of which are economic and essential for survival - and invest them in the conception, development, and production of artworks. The more of this extra time invested the better, following the rule that living labour as variable capital generates the surplus value, not the constant capital. The more they develop a type of artwork that calls for them to be present as continuously as possible, often in a performative capacity, the larger the amount of Mehrwert they create - even if that Mehrwert cannot always be automatically realized in the form of a corresponding price.

Constant capital is the costs of goods and materials required to make a commodity. Here then it becomes an intellectual aspect - the constant capital laid out to pay for time in bars and in lecture theatres. This gets embodied in the commodity once it comes into being. It does not create new value but disperses itself bit by bit in the commodities that are produced out of it. In contrast, variable capital is the aspect from which value, surplus value, can be derived. Variable capital is the amount of capital that is put towards labour costs. Diederichsen's presentation of it here suggests that once the artist has been able to get paid enough to reproduce the self, they can then devote all other time to artistic activities (or like Graw, convert unpaid time spent in the bar or café - ‘extra work in nightlife and seminar' - into an element contributing to the artwork.) The value transfers as surplus.

The absurdity of this is that the artist is presented here as an economic unit in his or herself. More usually in the case of surplus value, the variable capital would be a sum arrived at through a process of struggle or negotiation over wages. If the price gained for a commodity that cost £1000 of constant capital and £100 of labour costs were £1500, then the variable capital would have expanded by £400 - and that would be its surplus value. How this works for the artist in a kind of hermetic system is simply that the artist self-exploits, and the idea is that this can be ratcheted up, if the variable capital - the amount the artist accrues for the labour time - is kept small, while the time devoted to the artwork is great. The greatest portion being then the artist as performer, on the job constantly, who has received (or given his or herself) a certain amount to reproduce the self and even siphon-off some of this from other aspects of their life, but who then realises something far greater from the process. Diederichsen is aware of the non-fit of this to Marxist categories (the problem of the exploiter and exploited being joined in one person), but it does not deter him, indeed it suggests rather than the limits of his own theory, the problem of Marxism as applied to art. And he takes off again, outlining another type of value - speculative value. All of these curlicues of value then have a bearing on art's commodification and the rationalisation of art's value - or valuableness. The performance artist - the artist who performs the self and art - is key.

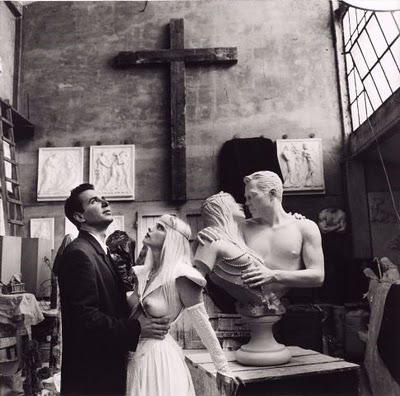

Diederichsen describes ‘a world of travelling minstrels and itinerant theatre troupes from pre-bourgeois, pre-capitalist culture, albeit now operating under the conditions of the digital age.' This is not particular to artists. Everyone is bottling up their ‘life force' and selling it. Musicians tour to make money - because the performance is unique, and to that extent ‘auratic', unlike the reproducible recorded song. Diederichsen writes of a ‘deregulated culture-industrial proletariat', all sent out to produce 'liveliness, animation, masturbation material, emotion, energy and other varieties of "pure life"'. Labour power has become life force or vitality, he notes. Porn, he states, bluntly is the economic model for this. In this regard, though Diederichsen does not say it, critical purchase might be re-attained, if Andrea Fraser takes on significance not so much as a market-reflexive figure so much as simply exemplary of today's culture-industrial proletariat, on the job, over and above the necessary, spilling the production of art into the night or into the intimate space of the bed, her life force commodified not labour power.

Image: Jeff Koons and La Cicciolina imitiate themselves, c.1990

The cultural scene depicted by Diederichsen is one in which semi-celebrities, artists, DJs, reality stars, flicker across the radar of success for a micro-moment, displaying or sweating out their ‘essentially interchangeable performance quality.' There is another, almost separate, cultural world of objects, which exude aura. It is no longer the aura that Walter Benjamin identified, as product of a unique existence in one single time and place. This is instead the object as carrier of a ‘secondary aura' or ‘a metaphysical index'. These objects - examples include limited editions of CDs or other highly-designed multiples - are posh commodities and they proliferate as luxury items in parallel and contradistinction to the proletarianisation of most producers. Such items become the common currency of a heterogeneous ‘post-bourgeoisie', who have ‘agreed on the visual arts as a common ground'. They produce the myth of an ideal artist in their own image: hedonistic, monstrous, restless, unstable, in love with precarity. A figure, it would seem, of Romantic passion stripped of political or critical import. Perhaps he is right in all this densely argued stuff, or perhaps the cogitations around price and value, the laying out and developing of familiar old critical categories - surplus value, price, aura, charisma and so on - are a pseudo-science, to make his own tenacious performance look more impressive. In any case, this pamphlet is a polemic rather than an empirical study. That has its value too. And at least it does fuck with the devil, mobilising some vision of horror, some sense of disgust, rather than just sup with it.

Esther Leslie <eleslie AT globalnet.co.uk> is Professor of Political Aesthetics at Birkbeck, University of London and is the editor of the journals Historical Materialism: Research in Critical Marxist Theory, Radical Philosophy and Revolutionary History. Together with Ben Watson she runs the website: www.militantesthetix.co.uk

Info

Isabelle Graw, High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture, Sternberg Press, 2010

Diedrich Diederichsen, On (Surplus) Value in Art, Sternberg Press, 2008

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com