Art, Autonomy and Automata

Last year digital arts platform Furtherfield extended itself into meat space, opening its HTTP gallery in Finsbury Park. Finn Smith visited the space, the boredomresearch exhibition ‘theatre of restless automata’, and the resident pussy cat

I was recently shown an article in The Sunday Times Style Magazine which extolled the merits of 'creative collectives'. If the title 'Group Therapy' wasn't nauseating enough, the article went on to claim that 'like all things Warhol, the creative collective is back.' Several groups were interviewed and made statements such as: 'We want to rent our art to businesses'; 'We could be arrested if we were caught selling drinks' and 'We hope to become a famous institution'. This left me feeling grumpy and disillusioned and I travelled to the HTTP artist-run space a cynical man, expecting the worst.

The sign on the metal door invited me to 'knock hard', so I did (with some reservation) and was welcomed into the gallery by Furtherfield co-founder Marc Garrett. As I quickly discovered, the encouragement of conversation, debate and social interaction is considered important by the gallery organisers and Garrett enthusiastically talked to me about the origins of the venue. I breathed a sigh of relief and began to warm to the idea of HTTP. As we talked, a black cat wandered out from the back room studios into the space and accompanied me while I observed the work. It certainly looks like a gallery in the traditional sense with white walls, spot lights and pamphlets describing the work but the presence of the cat is a reminder that this place is more than that: it is also a home, a studio and a meeting place.

The HTTP gallery is near Finsbury Park, next to the Green Lanes area of North London. The surrounding diverse community includes residents of Cypriot, Kurdish and Greek origin. The area is mainly comprised of residential buildings, small grocery shops, businesses and factories. The gallery itself is located in the Arena Business Centre in the type of warehouse unit that resembles a garage and is often used by small businesses selling such wares as bicycle parts, surf boards or computers. The unit not only houses the gallery at the front of the building, but is also partitioned at the back into a studio and living quarters of the directors. The deliberate location of the gallery away from central London is important to the group, as Garrett explained. They hope that the distance from the main tourist areas and arts facilities of the capital will mean that if people bother to turn up to HTTP they will either be local residents and students eager to participate, or those who have travelled from afar genuinely interested and enthusiastic about the group's activities. I expressed concerns that the presence of the gallery could trigger a process of gentrification which might antagonise local inhabitants but for the moment Garrett seemed to think that this was unlikely. Rather than driving existing residents away, the group hopes to encourage their participation through free exhibitions, launch parties, educational activities and conferences. They also seem unconcerned by the possibility that the relative geographic isolation of the venue and its focus on potentially daunting new media works might lead to low levels of public participation. If this were to occur it might serve to reinforce the notions of the artist as an eccentric lonely figure that the group makes a point of attempting to counter. The caution I urge is more eloquently expressed by Dave Beech in relation to artist-run spaces:

'Establishing a physical distance from the existing institutions is not a sure-fire strategy for attaining independence. Physical distance often turns out to be a red-herring, failing to guarantee that the space will be independent in the fuller sense. This is why art’s existing institutions can be re-used independently if they are treated as contested spaces. Artists and curators can gain independence by virtue of doing something else in the art’s established spaces. The first condition of art’s independence is not art’s isolation but its re-occupation of the cultural field, whether in setting up alternative spaces or by doing alternative things in existing spaces'.[1]

I am told that HTTP, in this punning instance, stands for House of Technologically Termed Praxis. The gallery was set up in October 2004 by the artists and curators of Furtherfield – an online platform launched in 1997. The London based, non-profit organisation was set up by Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow. As they explain in their ‘behaviour statement’ (noticeably 'behaviour' as opposed to the more authoritarian 'program') the group is committed to the 'creation, promotion, and criticism of adventurous digital/net art work for public viewing, experience and interaction'. They deem Furtherfield to be a collaborative effort and a means of bringing together, amongst others, artists, programmers, writers, activists and musicians to focus on network related projects. Garrett told me that he feels that the ever-expanding local and international community, as initiated and developed by the online platform furtherfield.org, has enabled them to offer their own form of challenge to the nationalistic Brit Art Label.

The gallery has recently received interim core funding from the Arts Council of England and this has allowed the group, after years of hard work, to begin to plan for the long term development of exhibitions instead of having to take projects one at a time. Whether this will deny spontaneity is yet to be seen but, as a result, the gallery is putting on artists talks, conferences and working with local colleges and students. One such conference was ‘Models for Collective Servers' [www.furtherfield.org/collectiveservers/] in which local artists involved with technology met to discuss ways of setting up server collectives in the wake of the Bristol Indymedia Server seizure.

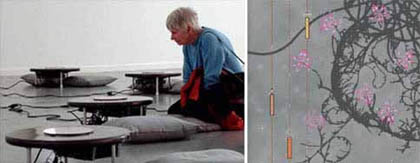

The recent exhibition 'theatre of restless automata' (September-October, 2005) is the work of Vicky Isley and Paul Smith who have been collaborating under the name of boredomresearch since 2000. The HTTP gallery is a relatively small, intimate space and this inevitably impacts on the presentation of the work. Three pieces, originally conceived as separate works, vie for attention in close quarters. As you enter the room you are immediately confronted by the work Biome Systems. It consists of four circular screens and lenses housed within, and extending slightly out from what appear to be dark grey lacquered frames. The frames are attached to metal legs which are in turn screwed to the wall so that the screens face the viewer at eye level. At first glance the screens might resemble modernist canvases with flat planes of colour, yet swaying and flitting movements across the surfaces alerts otherwise. Wires to the screens trail openly across the walls and floor and no attempt at concealing them has been made. I liked this contrast between the neatness of the objects and the mess of the tangled wires. It suggested that the artists were not afraid to remind the viewer that digital tanks, cages or universes are not truly autonomous and rely on the material world for electricity to power them. The press release describes the objects as 'portholes' but I would suggest that this allusion is slightly misleading: the viewer is not looking out of the physical structure of the building but into small containers that resemble petri dishes. Each screen features a dark swaying background with a scattering of star-like white dots and a red glow emanating from one edge. Occasionally, the mesmerising tranquility of the background is broken. Colourful, intricately patterned digital 'insects' burst on to the screen and appear to swim around the space, flitting randomly across the surface making watery squelching sounds and defecating stars as they go. At other times, insects appear to attack each other by firing bolts of light. Strange aggressive industrial sounds reminiscent of 'shoot em up' computer games are emitted when you least expect it.

On the wall opposite is fixed a single square shaped screen, this time the frame is a deep red. Again, cables trail openly down the wall, this time to a speaker on the floor. This piece is titled Ornamental Bug Garden and in contrast to the harsh sounds of the Biomes, emits almost continuous gentle sounds that resemble wind chimes and a tuning fork. The screen features a delicate plant like background and the ornamental digital space suits its name. A population of small white 'creatures' fling themselves around the 'garden' triggering flowers to spin, bubbles to be blown and lifts to rise.

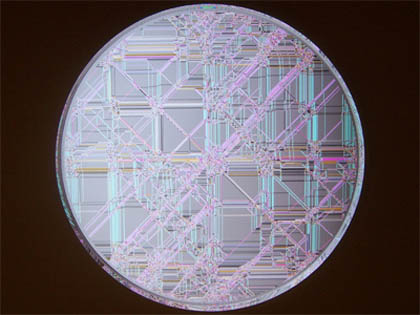

On the floor in between Biomes and Ornamental Bug Garden is the piece Random Seed. This consists of two circular screens framed within white disks standing on tripods. Of all the pieces they most clearly resemble petri dishes. The presentation on the floor means either hovering over them or kneeling down beside them to look into the lenses. A pale coloured digital mould appears to be slowly growing across the screens. These pieces are silent and contrast markedly with the wall mounted pieces.

I sat in a chair at the side of the room and found myself relaxing in the peace of the dimly lit room with the gentle sounds of Ornamental Bug Garden chiming in the background. I was however distracted from this meditative atmosphere when I noticed several rows of nails that had been hammered into the wall behind the Random Seeds piece. Hanging from each nail was a different plastic picture keyring. When I went up to them, I discovered via the accompanying literature that the images displayed on the keyrings were print-outs of what the artists had deemed to be the most visually exciting creatures (which it turned out they referred to as 'machines') that had been generated by the Biomes piece. There was no obvious criteria as to what constituted visually interesting. In terms of presentation the potential exciting tension between the ominous grey shaped Biomes and the opposing delicate Ornamental Bug Garden was diminished considerably by the placement of these keyrings that were being offered for sale. A lot of care had been taken in the making of these objects and the software but it seemed like the presentation of the work had been neglected. The screens were beautifully crafted objects but the images generated by the software were not exciting enough to sustain my interest for long. I left my first visit, impressed with the gallery having enjoyed my conversation with Marc about the space and decided to return the following week to see the artists' talk to decide whether the pieces were more than just elaborate executive toys.

The talk by boredomresearch titled 'Emergence and Poetics in Restless Automata' turned out to be clear, concise, informative and enjoyable. It was packed with humorous anecdotes (such as the story of Jacques Vaucanson's mechanical duck which had been designed to create the illusion of eating, swimming and excreting) to explain their influences. With the aid of a laptop and data projector they explained how they use software models to synthesise ecological systems populated by animated objects. They pointed out that without access to the source code, the works stand as 'new observable systems, for which only assumptions can be made about the rules by which they are governed'. They also shrewdly explained their interest in properties of emergence, as consequence of a computer program's execution, with an eloquent animation. A transcript of the talk can be viewed at [http.uk.net/docs/exhib6/br_talk.pdf]

Boredomresearch did not at any point pretend to be scientists researching and pushing the boundaries of evolutionary studies and artificial life:

As artists our interests in the mechanics of these dynamic systems differs from scientists’ or artificial life researchers’. Like scientists, we may reduce our observations of natural systems to a simple set of rules written as a computer program. Unlike scientists, we are not looking to extend our overall understanding of these systems or to create artificial life. Our enthusiasm is for the creative, aesthetic and poetic possibilities these systems hold for the creation of new observable artifacts of intrigue and beauty.[2]

The pair seemed happy and even mildly amused to think that people might approach the works and interpret them in highly imaginative and inaccurate ways. Until it was explained otherwise, I had fallen for the illusion and had originally assumed that the works were attempts at visually representing a process of natural selection that might occur in the real world. After the talk and a short break in which visitors were offered drinks in the garden, an online version of Random Seeds was launched. This was a good demonstration of the potential for Furtherfield to maintain its online presence whilst linking neatly to the gallery. Boredomresearch had in the past predominantly presented their work online or on CD-ROM so it was suited to the transition.

I left the gallery in two minds. I had enjoyed the talk and found boredomresearch to be refreshingly honest about their interests and intentions. However, I will admit that I did not find the images and sounds generated by the software particularly exciting and they did not retain my attention for long. They seemed a little familiar, glossy and benign and the well-crafted screens did little to allay this. The works, for all their ornamentation, lacked tension. Perhaps drama could be created if the behaviour of the automata were dependent on real world systems or events such as political polls, patterns of climate change, internet use statistics, weather systems or economic systems (as in The Planetarium which linked artificial life to stock markets and was shown as part of the 'Art Now: Art and Money Online' exhibition at Tate Britain in 2001). I was told that if the 'developments' in the pieces start to overwhelm the digital spaces, the artists judge the resulting messy 'white noise' as visually dull and start again. This seemed like a bit of cop out and I would have enjoyed more risk taking.

HTTP is an exciting new venue and given the interests of its directors has the potential to challenge what the social geographers Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin have called the 'Banalisation of Technological Mobilities':

Infrastructure services, and the huge technological networks that underpin them, seem immanent, universal, unproblematic – 'obvious' even. People tend not to worry where the electrons that power their electricity come from, what happens when they turn their car ignitions, how their telephone conversations or fax and Internet messages are flitted across the planet, where their wastes go to when they flush their toilets, or what distant gas and water reserves they may be utilising in their homes.[3]

It will be interesting to see if the gallery can entice more local residents and those outside the Furtherfield milieu to participate in future conferences and events. The artists' talk I witnessed seemed to be attended mainly by those with an affiliation to the group. Importantly though, HTTP was not set up opportunistically to catch the attention of the regular art market. It has been the result of much hard work by Marc Garrett, Ruth Catlow and the Furtherfield team and I get the feeling that the space will continue to develop and be used as a base for many fascinating projects.

http://www.boredomresearch.net/

[1] Dave Beech, http://www.variant.randomstate.org/22texts/Hospitality.html

[2] Transcript of boredom research talk 9/10/2005, http://www.http.uk.net/docs/exhib6/br_talk.pdf

[3] Graham, Stephen & Marvin, Simon, Splintering Urbanism, London: Routledge, (2003)

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com