Art and/or Revolution?

What's the difference between a commissar's propaganda and a constructivist's poetics of production? Marco Deseriis reviews Gerald Raunig's Art and Revolution and ponders some of the gaps in his aesthetic-political theory

There are books which are imbued with an anachronistic aura from their very release. Books whose untimely publication makes you wonder whether their moment has irrevocably passed or is perhaps still yet to come.

Such is the case with Gerald Raunig's Art and Revolution: Transversal Activism in the Long Twentieth Century, a dense reflection on the concatenation of European artistic and revolutionary practices of the last two centuries. A potential theoretical tool for the Seattle movement, the book hit the bookstores when the movement was clearly ebbing, and resurgent fundamentalisms, nationalisms and widespread anti-immigration feelings were reshaping the political climate in a conservative fashion. The paradox is that if there was a ‘right time’ for a book such as Raunig's, this ideal window of opportunity was no longer than the three months dividing the Genoa anti-G8 protests of July 2001 from September 11; that is, before the global state of war seized the stage from the Seattle movement. To be sure, (what is left of) the movement of movements continues to produce its own analytical tools. But what seems to be missing in the current phase is a political and imaginary space in which those movements can articulate theory and practice in their dialectical unity.

Image: Book cover

The shrinking of this space is particularly conspicuous for a book such as Art and Revolution, which tries to make a bridge between historic revolutionary processes such as the Paris Commune and the October Revolution with the radical interventionism of groups such as the Situationist International, Viennese Actionism, and the PublixTheatreCaravan. But this lack is somehow compensated through a dialogue at a distance with the Italian post-Marxist workerist theories of immaterial labour and the French post-structuralism of Deleuze and Guattari – theories that are themselves condensed forms of practice brewed in the social struggles of the 1960s and ‘70s.

But what is a revolutionary process? Raunig's answer is relatively simple: a revolution is a heterogeneous, machinic assemblage of three separate components – resistance, insurrection and constituent power. By following John Holloway's Change The World Without Taking Power, a book strongly influenced by the Zapatistas, Raunig argues that resistance and constituent power are inextricably tied because every ‘scream-against’ the powers that be is simultaneously a ‘movement of power-to’ that ‘create[s] the sort of social relationships which are desired.’i To be sure, this dialectics of resistance and constituent power was first articulated by Antonio Negri in the 1970s when the Italian factory workers' refusal of waged labour and exodus from the working place had the effect of pushing labour processes outside the factory walls, setting in motion new forms of political organisation and multiplying the sites of contestation throughout society.ii

As is well known, the main thrust of the operaist argument, originally formulated by Mario Tronti in Operai e Capitale (1966), and repeated almost 40 years later by Hardt and Negri (2004) is that ‘resistance is primary with respect to power’ or, as Raunig puts it, that there is a ‘relationship of dependency’ between the two.iii However, if social struggle simply preempted capitalist strategies, we would hardly be living in a pan-capitalist world today.

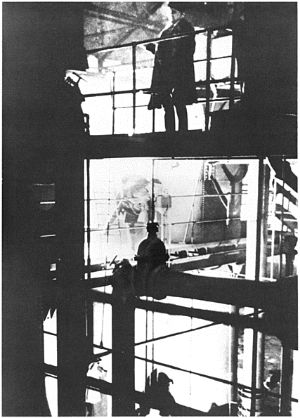

Image: Representation of Gas Masks, Moscow, 1924

Because living labour, the creative movement of ‘power-to’, is always at risk of being coopted by constituted power and caught in the bourgeois institutions of the modern State, insurrection – the third component of the revolutionary machine – ensures that the relationship between constituent power and instrumental power is an antagonistic one. In other words, what needs to be dispelled, and here Raunig follows Holloway again, is the illusion that constituent power may peacefully coexist with constituted power, or that cultivating ‘our own garden’ and ‘our own world of loving relations’ may naturally lead to a radically different world.iv Accordingly, Hardt and Negri write:

We must think of resistance, insurrection, and constituent power as an indivisible process, in which these three are melded into a full counter-power and ultimately a new, alternative, formation of society.v

Insurrection is thus the dynamic element of the revolutionary machine that by refusing to subordinate the principle of difference to identity, prevents constituent praxis from crystallising in institutional politics, and extends representation ‘all the way to the greatest and the smallest difference.’vi The Deleuzian distinction between organic and orgiastic representation is used here to suggest that it is the spontaneous formation of a plurality of self-governing bodies that prevents centralised revolutionary committees or parties from taking over and normalising a revolutionary process. For instance, the movement of the clubs, the formation of spontaneous organisations such as the comités républicains de vigilance (vigilance committees), and the prominent role played by women in the Paris Commune brought about an original experiment in direct democracy – which Raunig calls an ‘orgiastic state apparatus’ – in which no unified party, government or ideological line was able to fully override the micropolitics of local committees and assemblies.vii

In Art and Revolution, the Paris Commune serves as a historic example that allows one to think of alternative paths to the Leninist revolutionary project as a phase model that sets itself the primary goal of taking over the state apparatus to create a new society only after ascending to power. But if the history of the October Revolution demonstrates that this linear development is likely to lead to a structuralisation of the state, which tends to absorb all the autonomous forces of the revolutionary process, Raunig, following Guattari, argues that this threat can be forestalled by a transversal concatenation (a movement ‘across the middle’)

of art machines and revolutionary machines in which both overlap, not to incorporate one another, but rather to enter into a concrete exchange relationship for a limited time.viii

In considering the function of art in this concatenation, Raunig first analyses the peculiar trajectory of Gustave Courbet in the days of the Commune. While notorious painters such as Pisarro, Cezanne, Monet and Manet fled Paris to the countryside, the author of L'Origine du Monde decided to remain in the city, join the uprising, and even become a member of the Council of the Commune. In the aftermath of the bloody repression of the revolt, Courbet was put on trial for participating in the toppling of the Column of Place Vendome, which had been commissioned by Napoleon to celebrate the battle of Austerlitz. In spite of the fact that Courbet had proposed to move the column to a different location and had joined the Council of the Commune only after this had opted for its destruction, the artist was first sentenced to six months in prison and then, in a second trial held in 1874, fined an astronomical 323,091 Francs, forcing him to flee the country and eventually die in exile. In his ‘Authentic Account’ before the court, Courbet styled himself ‘as a peace-maker and preserver of art treasures, who used his role to ensure the safety of art treasures.’ix

According to Raunig, this episode – along with the mythic story of the artists' spontaneous defense of Notre Dame from the fury of the Communards who wanted to set the cathedral on fire while the government troops were besieging the city – proves that art and revolution failed to concatenate transversally in the Paris Commune. In Courbet's linear progression from art to revolution and back to art, the prototype of the bourgeois artist that clings to the abstract universalism and eternal value of art (in order to save himself from prosecution) is simply restored after a mad interlude. Thus, ‘the Courbet model embodies the model in which there can no be systematic overlapping of the revolutionary machine and the art machine.’x

And yet this missed concatenation does not mean that the transversalisation of art and politics is always unrealisable, but rather that its historic conditions of possibility were not mature at the time of the Commune. Even if Raunig hardly discusses the aesthetic sphere in its concrete historic development – and this is probably the major flaw of his analysis – in the last three decades of the 19th century, artistic activity in Europe is increasingly understood as an activity that differs from all others. This is reflected in the emergence of a series of artistic and literary movements such as symbolism and decadence that reject ‘the means-end rationality of the bourgeois everyday’ by declaring the lack of any social or political purpose for art.xi According to Peter Bürger, the emergence of the 20th-century European avant-gardes, that is, of a set of artistic movements that are no longer defined by the pursuit of a style or a particular form, but by their attack on the way art functions in bourgeois society, is the (paradoxical) result of a dialectical intensification of this process of autonomisation of art. It is because of the special status that art was granted throughout the 19th century that the avant-garde could ‘attempt to organise a new life praxis from a basis in art’ amidst the general politicisation and radicalisation of civil society arising during the great carnage of World War I.xii

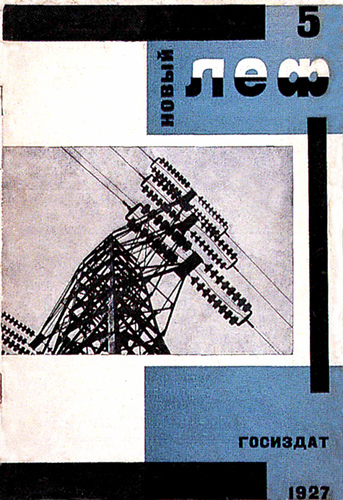

Image: Front cover of the magazine Novyi Lef (New Left), no.5 1927

This means that art reclaimed now a pragmatic and even an organising function, that is, the right to directly intervene into politics. While in Germany and Italy the defeat of the Spartacist uprising and of the socialist general strike marked a setback for the revolutionary movement, in Russia the October Revolution instigated artists to take on an active role in the context of collective appropriation of the means of production. Raunig focuses on the Leftist Front of the Arts (LEF), the most radical of the Russian avant-garde groups, and in particular on the collaboration between director Sergei Eisenstein and writer Sergei Tretyakov in developing an ‘eccentric theater’ based on a ‘montage of attractions’, that is, on a series of estranging and emotional effects whose function was to provoke and trigger spontaneous reactions in the audience by breaking the mimetic illusion of bourgeois theatre. This collaboration resulted in the production of two shows, Do You Hear, Moscow? (1923), and Gas Masks (1924), which applied the principles of Constructivism to theatre and, like Meyerhold's biomechanical plays of the same period, made use of constructivist scenic elements, daily objects and machinery instead of decorations and props. This pursuit of ‘realness’ was brought to its logical conclusion by Eisenstein's decision to set Gas Masks in a non-theatrical environment, the gigantic hall of the Moscow Gas Works on the outskirts of the city. Even though the show was mostly designed for factory workers, it encountered various production problems, prompting Eisenstein to interrupt the collaboration with Tretyakov and abandon theatre for the burgeoning Soviet cinema.xiii

Tretyakov, on the other hand, revived the LEF group, disbanded in 1924 by co-founding the journal Novyi LEF with Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1927. Then, the following year, when the first Five-Year Plan for the industrialisation and total collectivisation of agriculture was launched, he took literally the Bolshevik call ‘Writers to the Kolkhoz!’ by joining the Communist Lighthouse collective farm. The episode is recalled by Walter Benjamin in his famous essay ‘The Author as Producer’ where the German philosopher mentions Tretyakov as an example of a writer who does not limit himself to informing the readers, but actively tries to transform them into cultural producers by teaching them how to use modern technologies for literary production and propaganda.xiv

Image: Front cover of the magazine Novyi Lef (New Left), no.9 1928

But if Tretyakov's frenetic activity in the kholkoz is exemplary because of his ability to modify the production apparatus, the question that goes unanswered in Benjamin's and Raunig's texts is in what way Tretyakov's work can still be considered literary, or, to put it bluntly, in what way does it differ from that of a regular political commissar sent from Moscow to supervise the propaganda effort in the countryside?

Raunig's claim is that by going to the kolkhoz ‘Tretyakov arrived at his most radical strategy, almost outside the realm of art,’ that is, he was realising the avant-garde project of integrating art and life.xv This may be true, especially if we consider that by the mid-1920s Tretyakov had become – along with Boris Arvatov, Alexei Gan, and Nikolai Tarabukin – one of the leading theoreticians of productivism, a current that waged virulent attacks on all the avant-gardes that still claimed some autonomy of sorts for art. But if we read Tretyakov's activity against the backdrop of this ideological struggle, Raunig's claim that ‘Tretyakov's micropolitics’ created a laboratory in the kholkoz ‘waiting for concatenation’ and substantially external to ‘Stalin's molar apparatus’, becomes extremely problematic.xvi We shall now see why.

As Benjamin Buchloh notes, productivism marks a ‘paradigm-change’ within the Soviet avant-garde. Anticipated in 1923 by Ossip Brik's manifesto ‘Into Production’, productivism comes of age in 1925-6 when prominent constructivist artists such as Rodchenko and El Lissitzky realise that the socialist revolution

required systems of representation/production/distribution which would recognize the collective participation in the actual processes of production of social wealth, systems which, like architecture in the past or cinema in the present, had established conditions of simultaneous collective reception.xvii

With its modernist emphasis on the properties of the materials and their formal organisation into a coherent whole, constructivism had downplayed issues of distribution and audience. To be sure, in 1921 the leading group of constructivist artists that revolved around The Group for Objective Analysis had already embraced the principle that the kinetic life of materials and objects brought about by industrialisation undermined forever traditional, static notions of composition, and called for a new perceptual dynamic between artworks and audience based on interaction rather than contemplation.

But by the mid-1920s it became clear that recognising ‘collective participation’ in the actual processes of art production required more than attacking the bourgeois aesthetic canon based on representation. The institution of polytechnic factographs, production facilities in which Soviet workers could be trained as correspondents, reporters and photographers, was for Tretyakov and other productivists the next necessary step in overcoming the division of labour between manual and intellectual activities, repetitive and creative work, or, in Buchloh's words, to meet ‘the challenge of merging practices of signification with the methods of industry and production.’xviii

Image: Günter Brus, 'Selbstbemalung I', Action, 1964

Tretyakov's enthusiastic response to the call ‘Writers to the Kolkhoz’ thus proceeded from the ideological belief that art and writing have no value or meaning but in the operativity of factographic work. As previously noticed, the self-abolition of art and literature as autonomous spheres and their instrumental subordination to the ‘objective needs’ of the working class and the socialist revolution coincided with the termination of the New Economic Policy – which had afforded a certain cultural freedom – and the launch of Stalin's First Plan.

From this perspective, Boris Groys' assertion that productivism paved the way to the suppression of the avant-garde in 1932 and to the simultaneous elevation of socialist realism to the official aesthetic canon of the Soviet Union is hardly surprising. As a matter of fact, Groys' paradoxical claim that

the Stalin era satisfied the fundamental avant-garde demand that art ceased representing life and begin transforming it by means of a total aesthetico-political project [...] can be verified by looking at multiple statements of LEF ideologists such as Arvatov, Chuzhak and Tretyakov himself, who had invested art with the mission of building a new human being rather than ‘simply’ providing a different understanding of the world we live in.xix

To be sure, socialist realism restored representation and was therefore at odds with the abstract avant-garde, at least from a formal point of view. But since the latest avant-garde had managed to downplay formal exploration, the State apparatus had only to take it at its word, in a sense, by declaring socialist realism as the only definitive, aesthetic canon. ‘According to Stalinist aesthetics, everything is new in the new posthistorical reality,’ writes Groys.

There is thus no reason to strive for formal innovation, since novelty is automatically guaranteed by the total novelty of superhistorical content and significance.xx

But if the myth of the originality of the avant-garde was absorbed and superseded by the post-historical re-presentation of the Revolution as the ultimate Work of Art, this development was also partly rooted in the fact that avant-garde artists had longed to become engineers of the modern world well before the advent of productivism. As a matter of fact, as Groys notes, the often overlooked will to power of the avant-garde can be traced to the modernist claim that the entire world and ensemble of human activities can and should be used as materials for artistic activity.

Vladimir Mayakovsky's famous slogan ‘Let Us Make The Streets our Brushes, the Squares our Palettes’, Kazimir Malevich's ‘Wear the Black Square as a Mark of the World Economy’ or UNOVIS' ‘We Are the Plan, the System, the Organisation’ are all expressions of the same demand for power over a world that is to be made anew ‘according to a unitary artistic plan’ that accepts no limitations or challenges ‘by any other non-artistic authority.’xxi Drawing on these premises, Groys concludes that ‘there would have been no need to suppress the avant-garde’ if this had ‘confined itself to artistic space, but the fact that it was persecuted indicates that it was operating on the same territory as the state.’xxii

Obviously, one can object to Groys that the art domain cannot be determined a priori, and that one of the very functions of avant-garde research has been precisely to expand the scope of this domain and our understanding of what art is. Furthermore, it is objectively hard to assimilate Malevich's late-romantic search for a spiritual art expressing the ‘non-objective world’ of feelings to the über-materialism of late 1920s productivism. However, if we agree with Peter Bürger and other theorists that the core of the avant-garde project was to do away with the bourgeois autonomy of the aesthetic, and that this project was necessarily connected if not subordinated to the abolition of capitalism, it follows that the avant-gardes needed, and indeed often sought, a durable alliance with those forces that mastered the actual transformation of the conditions of production and society at large. In this respect, the emergence of productivism reflects the more or less conscious acknowledgement by various segments of the Russian avant-garde that since this transformation was now firmly in the hands of the Party, freedom of artistic intervention was in fact limited by the Party's agenda.

Image: Poster for the short-film for No Border No Nation event, by PublixTheatreCaravan, Viena 2007

All these considerations on the troubled liaisons between artists and political parties or movements go unaddressed in Art and Revolution, for at least two reasons. In the first place, Raunig chooses to analyse the concatenation between art and revolution only by looking at those groups that engage in political theatre and street actions. The Soviet theatre of attractions, the Situationist enragés of Nanterre, Viennese Actionists, and the PublixTheatreCaravan's interventions lend themselves to transversal concatenation insofar as their temporary nature allows them to escape the trappings of political representation and colonisation by the party or the state. Second, those groups are carefully selected because of their ability to transform, as Benjamin writes, consumers into producers, ‘readers or spectators into collaborators.’xxiii The visual and the plastic arts remain outside of the picture (one deduces, the author is not explicit) because they do not activate their audiences for a limited amount of time.

In regard to the first point, these performances and interventions cannot be isolated from their ideological context, but they have to be evaluated together with the revolutionary programmes and statements that inspired them – statements that called for a thorough transformation of the entire aesthetic sphere. This holistic tendency is epitomised by the avant-garde's vocation to use multiple media as part of an aesthetic strategy which aimed at overcoming the advanced specialisation of functions brought about by industrialisation and the capitalist division of labour.

Second, the transformation of audiences into cultural producers does not occur only in periods of social upheaval but is part of a long term historic process whose effects become fully visible with the deployment of cognitive capitalism. In this respect, emphasising insurrection over constituent power, orgiastic representation over organic representation, the tactical over the strategic, evades a more fundamental question, that is, why art and politics succeed or fail to concatenate in those ‘decennial intervals’ that divide one insurrection or revolution from the other.

Image: A reenactment of The Four World War by The Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army

To answer this question I believe it is necessary to address the emergence of art as an autonomous sphere – the major blind spot of Raunig's book. At the beginning of the 19th century, what Jacques Rancière has defined as the ‘representational regime of art’, i.e. the evaluation of an artwork in terms of its mimetic adequacy, collapses. Artworks begin to be identified only by their belonging to a specific sphere. Once the aesthetic achieves its separate status, Rancière argues, the ‘traditional hierarchies of subject matters, genres and forms of expression separating objects worthy or unworthy of entering in the realm of art’ come to an end, along with the traditional hierarchy between intellectual and sensory faculties:

In his Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man Schiller drew, after Kant, the political consequences of that de-hierarchisation. The ‘aesthetic state’ defined a sphere of sensory equality, where the supremacy of active understanding over passive sensibility did not work out any longer [...] Schiller opposed that sensory ‘revolution’ to the political revolution as it had been implemented by the French Revolution. The latter had failed precisely because the revolutionary power had played the traditional part of the Understanding – meaning the state imposing its law on to the matter of sensations – meaning the masses.xxiv

With its position of withdrawal, its search for the inconnu and for what cannot be fully rationalised, Aestheticism, as we have seen, embodied the artist's great refusal of bourgeois rationality and of the division of labour between intellectual and bodily functions. This counterposition of the sensory equality of ‘the aesthetic state’ and the political equality of the Rights of Man, however, is not only internal to the bourgeoisie, but affects also the revolutionary movement and the working class. One may think of the tension between the desiring politics of utopian socialism and scientific Marxism in the 19th century, the European avant-gardes and the Third International in the 1920s, the hippies and the 1968 revolutionary groups, the feminists, the punks and the traditional politics of unions and labour parties in the 1970s, and so forth.

It is only by analysing the art machine's own specific components – not as a mere reflection of the revolutionary machine – its will to power, its own organisational forms, and its peculiar ways of understanding what is equal and what is just, that the art machine and the political machine can be articulated in their reciprocal difference. This is the best antidote to the risk, against which Raunig rightly warns us, that one of the two may incorporate the other.

Marco Deseriis <snafu AT thething.it> is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Media Culture and Communication at New York University

INFO

Art and Revolution: Transversal Activism in the Long Twentieth Century

Semiotext(e), 2007, 320 pp., $17.95/£11.95

FOOTNOTES

i John Holloway Change The World Without Taking Power: The Meaning of Revolution Today, London/Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press, 2002-2005, p. 153. Cited in Raunig, p. 42.

ii As Harry Cleaver points out in his introduction to Negri's Marx Beyond Marx, ‘the positive side to revolutionary struggle is the elaboration of self-determined multiple projects of the working class in the time set free from work and in the transformation of work itself. This self-determined project Negri calls self-valorization.’ In Antonio Negri, Marx Beyond Marx: Lessons on the Grundrisse, New York: Autonomedia, 1991, p. 25.

iii On page 52 Raunig suggests that in his Foucault (1986) book Deleuze was the first to use Tronti's analysis to explain the intertwinement of power and resistance in terms of a preeminence of the latter over the former. In actual fact, those theories had already been elaborated by Negri (1979) and other workerists throughout the 1970s.

iv Holloway, Change The World, p. 37. In Raunig, p. 45.

v Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, ‘Globalization and Democracy’, Paper at Documenta XI, Platform 1, Vienna, 20/4/2001. In Raunig, p. 47.

vi Raunig, p. 80.

vii Raunig, pp. 80-96. On the distinction between orgiastic and organic representation cf. Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, pp. 48-50.

viii Raunig, p. 18. On the concept of transversality cf. Félix Guattari, ‘La Transversalité’ in Psychananalyse et transversalité. Essais d'analyse institutionelle, Paris: La Découverte, 2003 and Gerald Raunig, ‘Tranversal Multitudes’, September 2002, http://eipcp.net/transversal/0303/raunig/en

ix Raunig, p. 109.

x Ibid., p. 112.

xi Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, Minneapolis, MI: University of Minnesota Press, p. 49.

xii Ibid.

xiii Cf. Mel Gordon, ‘Eisenstein's Later Work at the Proletkult’, The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 22, No. 3, Analysis Issue (Sep., 1978), pp. 107-112.

xiv Benjamin recalls how during two lengthy stays at the commune Tretyakov set about the following tasks: ‘Calling mass meetings; collecting funds to pay for tractors; persuading independent peasants to enter the kolkhoz [collective farm]; inspecting the reading rooms; creating wall newspapers and editing the kolkhoz newspaper; reporting for Moscow newspapers; introducing radio and mobile movie houses, etc.’ Walter Benjamin, ‘The Author as Producer’ in Reflections New York: Shocken Books, 1955-1972, p. 223. Raunig lists Tretyakov's extensive self-report of his own work in the kolkhoz on pp. 165-67.

xv Raunig, p. 169.

xvi Ibid.

xvii Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, ‘From Faktura to Factography’, October, Vol. 30 (Autumn, 1984), p. 94.

xviii Ibid, p. 107.

xix Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic, Dictatorship and Beyond, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 36.

xx Ibid., p. 49.

xxi Ibid., p. 21. T. J. Clark argues that UNOVIS, the group founded in 1919 at the Vitebsk Art School and led by Kazimir Malevich with the participation of El Lissitzky, integrated art and Bolshevik propaganda to build an independent sphere of action on top of revolutionary politics. cf. T. J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999, pp. 224-97.

xxii Groys, p.35.

xxiii Benjamin, op.cit., p. 233.

xxiv Jacques Rancière, ‘The Politics of Aesthetics’, available at, www.16beavergroup.org/mtarchive/archives/001877.php

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com