Architectures of Dereliction

Two recently published books - Louis Moreno and John Alderson's The Architecture and Urban Culture of Financial Crisis and Sarah Glynn's Where the Other Half Lives - assess the damaging impact of financialisation on built environments and urban housing. In his double review, Owen Hatherley identifies architecture as a prime casualty of neoliberalism's de facto Non-Plan

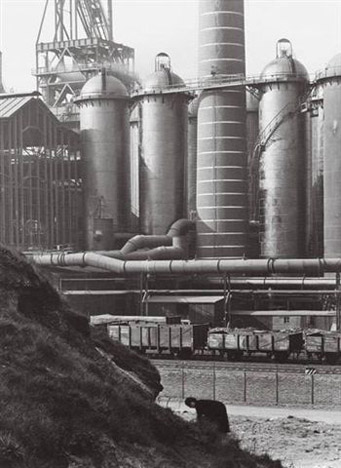

The financial crisis has often been depicted through architectural images. Since the banking crash of 2008, these images have been circulated, usually online, and gazed at as elegantly apocalyptic portents, as if to say ‘what we are now you will all be, soon'. Foreclosed houses in southern California, unoccupied apartment blocks in Leith surrounded by slurry, closes upon closes of desolate suburbs on the outskirts of Dublin, countless empty shopping arcades in Japan, practically any photograph ever taken of Dubai - all are striking images, and all of them have perhaps too often occupied the space which might otherwise have been filled with analysis of the systems behind the images. When peering through a monitor at the subprime dystopias, it's worth remembering an aphorism of Bertolt Brecht: a photograph of a factory tells us almost nothing about that factory. He was talking about the New Objectivity, the industrial photographs of the likes of Albert Renger-Patzsch, with their beautiful, depopulated images of machinery and empty space, but the claim could be easily extended to the photo-essays of dereliction.

Yet, although flicking disinterestedly through the coffee table dereliction tomes may not be a particularly insightful way of deciphering the causes and effects of the ongoing financial chaos, there's no good reason why architecture itself should not be the focus of any such analysis. In fact, the collapse of an earlier capitalist settlement, the Keynesian ‘glorious years', was accompanied by an analysis centred on architecture. Manfredo Tafuri's architectural books of the 1970s were explicit interventions into what Antonio Negri called The Crisis of the Planner-State; a ruthless, bleak intellectual history of modernist architecture, explicating it as the ‘built ideology' of social democracy, the place where its contradictions and compromises could be shown at their most explicit.

Image: photo by Albert Renger Patzsch

Unsurprisingly, given the politics of the time, Tafuri concentrated on capital's side of the settlement, which made the despairing, relentless nature of his critique very amenable to those who had little interest in defending (or an active interest in destroying) the real gains of that era - council housing, welfare and the interventionist planning that curbed the interests of capital. Yet the current crisis seems to have thrown up no comparable critique of the collapse of the non-planner state or its architectural embodiments. In fact, Tafuri's critique of social democracy is repeated as if it still describes our own situation, as if planning, benefits and public housing were the sources of contemporary urbanist ills as opposed to property speculation, bonuses and city-centre apartments. This strange, if politically useful time-lag can be seen at work in the cult of the ‘informal settlement' (or ‘the slum's got so much soul', as the Dead Kennedys pre-emptively put it in 1979), in the laments over alienating tall buildings and the amazingly still-current cliché about the urban despoliation perpetrated by post-war town planning. These two books, both of them worthwhile, if very, very different, represent some kind of way out of this impasse.

Sarah Glynn's Where the Other Half Lives is an excellent, and fairly straightforward defence of public housing and a catalogue of the various subterfuges and attacks it has been subject to since the 1970s. It is put out by a political publisher, written in an immediate, accessible and agitational style; while the other book is something rather more tricksy, a document of an academic seminar redesigned into an elegant object, limited to 100 copies. The Architecture and Urban Culture of Financial Crisis is a collection, left apparently almost completely without post-production, of the papers delivered during a seminar at the Bartlett School of Architecture, London, held on 24October 2008 - the point when the extent of the crisis became clear. The date is proudly displayed at the top of the volume, above the title, flagging up the contributors' prescience, the immediacy of events, the sense of talking while the bankers were throwing themselves from the towers just outside. In truth, however, it's a mixture of attempts to think outside of the current urban, economic and architectural conformism and more ‘realistic' discussions that stay within its terms, with greater or lesser lip service to the need for more ‘social' or ‘progressive' ‘solutions'. That sense of conflict, though implicit, enlivens the volume; an underlying tension which frequently threatens to come to the surface.

The introduction by Louis Moreno sets the scene appropriately by referring to the ‘skyscraper index', the so far practically infallible means of predicting a financial crash, formulated by an economist at Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein in 1997. Whenever the tallest building in the world appears, the bust is either round the corner or in progress, as it proved to be when the Burj Khalifa was opened early this year, with even its name (formerly the Burj Dubai) changed as a thank you to the potentate who bailed out the defaulting emirate. The index is instructive because of its focus on architecture as symbol and the essential mysticism of finance capital. It also searches for cultic portents and signs, or edifices which, even in their most genuinely ‘iconic' form - the Empire State Building which was half-empty for decades - were as much a phallic potlatch as a machine for making money. A set of newspaper and magazine covers deploying doomed skyscrapers as financial-crash symbolism makes the point equally clearly. The volume is intelligently illustrated throughout, mainly through its juxtaposition of images and text, which comment on each other rather than leaving the photos standing mesmerisingly on their own - boarded-up terraces next to new office blocks promising an ‘advanced business life environment', or advertisements which display the bizarre pornography of property. At Richard Rogers' One Hyde Park, the sign in front of the steel frame reads ‘Luxury is realised when service is intuitive and goes beyond obligation'.

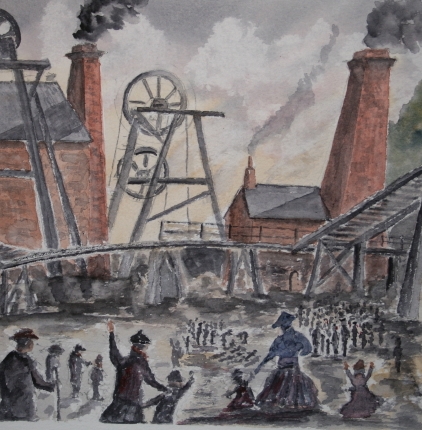

Image: Robert Sharples', The Tyldesley Mining Disaster of 1858

The opening keynote paper by town planning grandee Professor Sir Peter Hall is more an example of the thinking that landed us in this mess than it is of ways out. Hall was, along with Paul Barker, Reyner Banham and Cedric Price, the deviser of ‘Non-Plan' popularised through a very influential special issue of New Society in 1969, where this group of (by no means right-wing) critics, planners and architects advocated the total abandonment of planning controls. They presumed that the result would be a discontinuous funfest, a ludic landscape of leisure and pleasure. With the relaxation of planning controls by Nicholas Ridley in the 1980s, however, Non-Plan resulted in giant retail and entertainment complexes, both inside (Docklands) and, more commonly, outside of the historic city. If they're pleased with that landscape, bully for them. So it's difficult to find a figure, other than Hal, that represents current common sense on these issues. But, unlike the planners of the 1960s, the non-planners have never been called upon to repent for their actions.

Nonetheless, a repentant tone is struck with the title: ‘Come Back Schumpeter, Come Back Keynes, All is Forgiven'. It would be more fun if he'd written a paper called ‘Come Back Gropius, Come Back Abercrombie, All is Forgiven', though we'll let that pass. The paper charts the recent replacement of the (fairly risible) claims to have ended boom and bust with a renewed respect for the two economists: Nikolai Kondratiev, with his emphasis on predictable ‘waves' of capitalist development and collapse; and Joseph Schumpter, with his claim that capitalism thrives - exists - through a constant process of ‘creative destruction'. Hall, with some aplomb, follows these theories through urban space. From Lancashire in the late 18th century through to Silicon Valley in the 1970s, clusters of new industries have grown up in unpredictable areas, created new forms, and - although needless to say this is unmentioned - created novel forms of immiseration along with their technological novelties.

There is, in itself, little to disagree with in Hall's account of these shifting centres of manufacturing and information - it's engaging, beautifully illustrated, informative - but completely without any kind of critical bite. Tracking the shifts from Cottonopolis to Detroit to California, the end result is a Silicon positivism, where, unsurprisingly, the industrial economies that service the post-industrial valley - i.e. the Chinese assembly lines that manufacture their products - are ignored. There is a shift in register from excited and laudatory to uncertain and tentative when Hall discusses the post-industrial wastes left when the wave (as it were) has passed from one geographical area to another. He reserves the most praise for the investment in green technology in Germany. Laudable enough perhaps, but the examples seem less impressive. In Dortmund, Hall is impressed to see that former steelworks have become ‘major technology parks, not just disguised business parks' (the distinction is a little opaque), and similarly sanguine at the conversion of textile mills into arts centres. He then turns to advocate much the same solution for the less glamorous outposts of the former Cottonopolis, the conurbation which began the whole process two centuries ago. In Burnley, he is pleased by proposals by the late Tony Wilson to turn mills into ‘creative centres'. He concludes that we need to ‘reorganise [...] urban regeneration around the creative sectors', as if this means much more than a section of the local population becoming part of a service industry around the galleries, arts centres and their attendant coffee concessions, while others do the ‘creating'. The eventual upshot of Hall's argument is that these waves are essentially uncontrollable - all we can do is respond to them, deal with their consequences as best we can. Irrespective of Hall's cheerful erudition, his is a deeply fatalistic argument, and the suffering the creative destruction incurs is unimportant. Don't worry about the financial crisis, there'll be another wave along in a minute...

![]()

Image: Silicon Valley

Two other papers in The Architecture and Urban Culture of Financial Crisis are in a similarly technocratic vein, although with differing results. In his essay ‘Geographical Concentration in Finance', Dariusz Wojcik charts a similar geographical progression to Hall, this time in finance rather than technological innovation. He charts the movement of the centres of financial capital from Italy in the 14th-15th centuries, to the low countries, to the City of London, where it has remained for centuries, and for the last century along with Wall Street. Much of the paper is taken up with explicating the long-term nature of these movements and, implicitly, how they are unshaken by the periodic crashes: Wall Street and the Square Mile survived 1929. There is little serious competition, (financial, not industrial), from China or the Eurozone that is likely to replace them in the foreseeable future. With reference to the financial crisis and its architecture, though, Wojcik finds a near-total geographical disassociation. ‘To invest successfully in real estate [...] you need to be close to the places and firms involved and hence the market's scope is likely to be local and geographical concentration limited.' Of course the financial crisis was caused in part by a disjunction, through the dependence of the entire edifice on some deeply mundane structures, with the periphery having its revenge on the centre: ‘the fortunes of the global economy (were tied) to the changes in prices of ordinary homes in places like suburban Detroit and Kansas City.' Similarly, Wojcik finds that a direct link between finance capital and a ‘manufacturing hinterland' behind it has not been necessary for some time.

For all their neutrality, these are still interesting essays. One, however, has escaped here from a blander book altogether - ‘The Differential Effects of Financial Constraints on Workplace Demand', by Davida Hamilton of DEGW, ‘the leading international strategic design consultancy'. Here, for all the warmth and cheer of the rhetoric, you can see a mode of thought that was completely unprepared for the financial collapse. The paper is based on research for Northamptonshire Council on how to ‘intelligently intensify' the space in their workplaces, or more specifically, an investigation into ‘what portfolio of workspaces they needed for the new jobs they wanted to create'. The specificity may be interesting enough to specialists in the area of office organisation, but what is irksome is the venture into wider theorisation about contemporary work. There are, according to DEGW, ‘six generic workstyles', which are as follows: Visionary, Corporation; Service Processing; Goods Processing; Institution; and Research. These are more closely linked than they appear - the Visionaries and the Corporations both require ‘good transport nodes, good quality people and a good lifestyle offering'. There is no conflict, no tension, no exploitation in these imaginary workplaces, or at least nothing that can't be ironed out through ‘good design'. In the early '70s, when Norman Foster tried to design industrial peace through having bosses enter through the same doors as their workers, this might have had a certain naïve political import, but in a context where income differentials have spiralled to practically feudal levels, it's farcical. There is no detectable sense here that the crisis might make us think differently about the future. So, in the very midst of the greatest crisis for capitalism in 80 years, Hamilton muses, that in the event of the inevitable redundancies and bankruptcies, in which even the Visionaries will be hit hard, ‘I very much hope that the R&D sector which stretches from the urban to the peri-urban will retain its underlying growth and can keep some of the other businesses moving forward.' Indeed.

Aside from Matthew Gandy and Louis Moreno's pithy summations bookending the volume, the sharpest paper here is by Andrew Harris of UCL's Urban Laboratory - a detailed and, at times very funny analysis of the intertwining of ‘Art and Finance in Contemporary London'. The direct connections between the two may be assumed, but the precision here is interesting - it is useful and amusing to know which Hedge Fund manager is buying which piece and why, but more pointedly, Harris analyses the areas in which the two forms of semi-mystical but extremely lucrative capital have taken on a family resemblance. ‘It's notable how some investors are portrayed in the media with a certain mystique, equivalent to the aura connated on certain artistic geniuses - so for instance the ‘legendary' Warren Buffet. In spatial terms, meanwhile, Harris reminds us that the emergence of the dominant spectacle-art of the last two decades was not just contemporary with the City of London's expansion, but was funded by the same bodies. The pivotal Freeze exhibition of 1988, which made the names of many of today's most successful practitioners, was ‘held in a Port of London building in Surrey Docks and it was mounted with help from the London Docklands Development Corporation and had sponsorship from Olympia and York who were the subsequent builders of Canary Wharf'. Given that the interests of finance capital and the ‘creative industries' were entwined even at this apparently early, ‘underground' moment, it's strange that the likes of Peter Hall should imagine the creative and financial services to be potentially opposable forces, rather than one being the by-product of the other.

Image: Golden Lane Estate by Bon, Chamberlin and Powell, 1952

Elsewhere, the volume includes a rather off-kilter, but very interesting essay by Lawrence Webb on the '70s film The King of Marvin Gardens, in which the rise of gambling and real estate in Atlantic City, New Jersey, serves as an exemplar for a wider process. Another essay by policy adviser and academic Max Nathan, ‘Counting Cranes', develops an analysis of one of the most obvious but seldom analysed urban forms thrown up by the '90s/'00s boom - the city-centre apartment. Nathan finds that, although government regulation was minimal, government funding was often forthcoming for these schemes, the sort referred to alternately by developers as ‘stunning developments' but, more pithily, by Laura Oldfield Ford as ‘yuppiedromes'. Nathan, however, finds students as much as ‘young professionals' to be the usual tenants of inner-city projects (although their built form - the usually grotesquely shoddy speculative Halls of Residence built by developers such as Unite - are unmentioned). The title is taken from a statement by the leader of Liverpool City Council, which exemplifies nicely the rationale of urban regeneration - ‘I was in New York talking to some of the city leaders there who had turned the city around, and I said, you know, how did you start the process, and they told me ‘You talk up the city to everyone you can, you sell it and sell it, and then you look for the big cranes on the skyline'. Both the internationalism and the banality of the ‘process' is nicely summarised here. These are Potemkin cities, hiding (and often directly expelling) the previous inner-urban population, and Nathan finds the eventual collapse of the market entirely unsurprising given the extent of the speculation and the poverty of the product.

Only at one point does the volume confront the epicentre of the crisis, in an essay on the architecture of the City of London: ‘Autistic Architecture - (Re)imagining the Square Mile', by architect and academic Maria Kaika. She argues that the City faced enormous pressure throughout the 20th century to modernise its building stock, which it resisted for decades, before making a belated stab at a Manhattan skyline in the last fifteen years. The portrait of an insular institution, ‘London's Vatican [...] the ultimate boys' club', is convincing enough. Kaika finds that international architecture and international finance were resisted as a matter of pride until global consortium banks and skyscrapers appeared in the 1970s. The new towers are described as both a populist gesture, a skyline of ‘shards', ‘gherkins' and ‘cheesegraters', in order to give a grinning face to an ‘autistic' typology, one is entirely closed to the public, buildings that are ‘speculative objects or branding objects'. I don't intend to dismiss an interesting essay by pointing out the rather enormous historical ellipsis at the heart of it - although there's no doubt that the square mile's architecture was a byword for backwardness from the 1910s to the 1950s, the Corporation of London did not wait until the late 1990s before modernising itself. In the 1960s it attempted to redevelop itself in a far more spatially ambitious manner than in today's late Manhattanism, through the network of Highwalks that criss-crossed the City, or through the shockingly minimalist comprehensive redevelopment of London Wall - and these glass filing cabinets certainly lacked the ostentatiously domestic, friendly form of the recent towers. These towers and walkways were demolished in the 1980s and 1990s in favour of lower-rise, ‘traditionalist' (and gated) spaces such as Broadgate, before a mutated modernism reclaimed the city at the end of the '90s.

This isn't merely a point about architectural history, but one about the influence of particular political moments over institutions, even one as seemingly untouchable as the City. In the '50s, the Corporation of London did something which would now be seen as practically socialistic - it paid for the extremely modernist Barbican private-public housing scheme, but more interestingly, it bankrolled its wholly public precursor, the Golden Lane council estate. That an institution as reactionary as this would invest in a large scheme of public housing - and a particularly well-designed scheme at that - is a reminder that, when its power was threatened, or at least curbed, during the social democratic interregnum, the Corporation involved itself in something which the outgoing Labour government would have considered dangerously left-wing. We should remember that, if according to Tafuri architecture is ‘built ideology', and the dominant class dictates the form of architecture, that ideology and class dominance is not necessarily fixed. Which brings us to Sarah Glynn's book, an inspiring defence of a built form that has in recent years been patronised by some on the left and roundly denounced by the right - the council estate. Where the Other Half Lives is not, despite its title, a book about the specific spaces where the poor live internationally - there's no analysis here of the ad hoc informal slums, nor of the landlord-dominated housing markets, although Glynn clearly regards state-provided housing as a viable alternative to both. Rather, it concentrates very directly on public housing, its potentials and its often very grim realities - the housing the poor have periodically fought for, rather than the housing they have ended up in.

Image: Peabody Trust's Antony House on the Pembury Estate in Hackney providing 30 units of shared ownership accommodation

The essays in the anthology are mostly by Glynn herself, and are largely taken over by other authors when areas outside the UK are the focus. The opening essay, ‘If Council Housing Didn't Exist, We'd Have to Invent It' concentrates on what differentiates council housing from the superficially similar social housing provided by philanthropic institutions - the Peabody or Guinness Trusts and their ilk. It is, she writes, the difference between something provided as charity and something claimed as a right, as ‘charity', which was a swearword for the generation that remembered the means test, becomes an increasingly commonsensical good. The privatisation of council housing is usually via these charitable bodies. In a typical large-scale regeneration scheme, Park Hill, around three-quarters of the former council flats are to be sold on the open market, with the rest a ‘social' rump controlled by the Manchester Methodist Housing Association. This will no doubt only accelerate under the Conservative Liberal coalition, with its rhetoric of charity and responsibility.

Like the NHS, council housing is funded out of taxes rather than from the largesse of the philanthropist, but the case for it is more extensive than that. Unlike a local authority, you cannot vote out the Peabody Trust, you cannot stand for election in it, and most likely you can't picket its headquarters, as you'll have no idea where it actually is. Glynn argues that Council housing, especially when combined with the active co-operatives and tenants associations developed in the '70s, is by some measure the most democratic form of housing, as well as the cheapest. It was not something offered out of kindness by technocratic governments, but something fought for over generations; a concession which was initially granted as a safeguard against revolution after the First World War. The more politicised the city - Glasgow, Sheffield - the more dominant council housing would be. This is also seen in the forays outside of the UK that make up one-third of the book - an excellent essay profiles Sweden's extensive network of social housing, which came under attack from the 1980s onwards - although the extent of the damage was limited by the sheer amount there was to destroy, the need to conform to the ‘Anglo-Saxon model' occurred here too. Meanwhile, essays on the United States show an already heavily circumscribed public housing system battered to breaking point by moralising and invasive initiatives - hence the ‘property-owning democracy', and all those foreclosed houses.

Two-thirds of the book is devoted to the UK. Here, Glynn's introductory essays are instructive for their argument that the ‘problem' estates obsessed over by tabloids and guilty urbanists were always a very small minority of estates, rising from 5 percent only after council housing began to be decimated in the 1980s. The problem with council housing is that in being state-owned, it is uniquely vulnerable to changes in policy. This was made particularly clear through the sell-offs of council housing popular since the 1980s, either as a means of gerrymandering, as in Shirley Porter's ‘Building Stable Communities', or for more straightforwardly ideological reasons, as in John Prescott's ‘Building Sustainable Communities'. The result in both cases is population transfers which replicate the mass displacements of the slum clearances that created the space for council housing in the first place, this time without the prospect of anything better for tenants. This leads to one of the most important arguments in Where the Other Half Lives - the attack on the ideology of regeneration, and its effects on the surviving remnants of council housing.

Regeneration, a term which most contributors to The Architecture and Urban Culture of Financial Crisis assume to be a good idea which fell under Blairites, is here depicted as a ‘Trojan horse', a more-or-less surreptitious means of privatising, limiting or disciplining council housing and its inhabitants. This is itself closely linked to financialisation, and not only through the indirect consequences of city-centre property speculation: for instance, ‘the Scottish government's Regeneration Policy Statement took its lead from a report by the Royal Bank of Scotland that promoted "regeneration" as an opportunity for the growth of private business through the privatisation of public services.' The main instrument for the regeneration of council housing is through ‘tenure mix', something which even commentators who should know better present as a panacea for the problems of housing estates. The main upshot is always the limiting of council housing, through the sell-off of a percentage to private developers - exacerbating a housing shortage which, as Glynn points out, results in state subsidy for landlords, in the form of Housing Benefit payments. In new-build schemes, meanwhile, mixed tenure results in a melange of speculative housing and ‘affordable' units which, more often than not, are for ‘key workers', shared-ownership and so forth, rather than council tenants, who at best may find themselves as housing association tenants in a handful of the new schemes.

This book is a brilliant, compulsive and passionately written case for the continued importance of council housing, without means testing, mixed tenure or Methodists, and it should be read by anyone interested in the subject. There is one curious absence here, although the book doesn't suffer from that loss especially: aesthetics, or architecture itself. If there is a class architecture of financialisation - the Gherkins, the yuppiedromes - then is there a potential class architecture to counter it? Here, Glynn's argument is essentially that architecture is a distraction. This isn't argued out of anti-architectural philistinism - she claims that potentially the reason for the success of some council housing schemes is the sensitivity of their design, citing the Byker Estate in Newcastle as a particularly famous example. It's more, she argues, because hand-wringing over ‘eyesores' is used as a smokescreen for the expulsion of populations. In a study of regeneration in Dundee, for instance, she quotes its central aim as ‘getting rid of the ugly bits', i.e the tower blocks, to leave a more ‘historic' skyline in its place; and the ugly people in the ugly bits can go too, as a happy side-effect. Glynn has no fastidiousness about the look of these places, and if damp can best be reduced by clipping cladding onto the concrete or brick, then so be it. The photographs of buildings here are illustrative, not aestheticised - while The Architecture and Urban Culture of Financial Crisis manages to make that which it critiques look darkly attractive, the images of council housing here are fairly mundane, while avoiding tabloid cliché. If there is a visual or architectural case for council housing, it is mostly unmade here.

For over 30 years now, council housing has been reduced (inaccurately) to the image of the monolithic tower block, and it receives a partial defence here. Generally needing little more than a concierge and proper upkeep, they also provide, not uncoincidentally, the kind of imperious urban panoramas which are habitually sold as part of city-centre apartment complexes, only for significantly less money and with significantly larger rooms. Whether we can ever regard these stigmatised forms as our architecture, rather than an architecture we defend as best we can for want of something better, is another matter. Architecture, as these two books explain well in their own ways, is at the heart of recent political crises and conflicts, though nobody seems to have told architects themselves. If there is to be a new social architecture to counter the architecture of neoliberalism, as Glynn advocates, it might need new forms and new architectural ideas in order to make its case. At this point one of Tafuri's phrases comes to mind: ‘there is no class architecture, only a class critique of architecture'; and another from his contemporary Mario Tronti, who claimed that the council housing of 1920s Vienna created a form ‘within and against capitalism'. These two books occupy the space between these two claims.

Owen Hatherley <owenhatherley AT googlemail.com> is a freelance writer on political aesthetics for, among others, Building Design, the Guardian and the New Statesman, and a researcher at Birkbeck College, London. He is the author of Militant Modernism (Zero Books, 2009)

Info

Louis Moreno and John Alderson (editors), The Architecture and Urban Culture of Financial Crisis - The Bartlett Workshop Transcripts, London: Figaropravda, 2009

Sarah Glynn, (ed.), Where the other Half Lives - Lower Income Housing in a Neoliberal World, London: Pluto Press, 2009

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com