Anti-Disciplinary Feedback and the Will to Effect

'Double Negative Feedback' expresses the hope that the chaos unleashed by the cybernetic loops

The recursive forms of feedback made strange bedfellows out of cold war cybernetics and tripped-out psychedelia. In a reworking of a talk given at the Showroom gallery's Signal:Noise event, Lars Bang Larsen reads counter-cultural ‘good vibrations' literally and politically

Cybernetics may seem like an unlikely source of influence for psychedelia, if by this one understands plasmatic visual styles and a pastoral ethics that revolved around inner truth. Perhaps for this reason it remains under-theorized aspect of the '60s. However one need only consider that LSD clichés such as ‘turning on' and ‘tuning in' are machinic figures of speech. There is also anecdotal testimony, of course, such as how Apple founder Steve Wozniak conceived of the PC on an acid trip and tested the first microchips in Grateful Dead light shows.

Beyond this, feedback became a composite figure of life, self-organisation and shared listening in psychedelia's anti-disciplinary politics. The concept of the anti-disciplinary juxtaposes the anti-authoritarian and the interdisciplinary, following Michel Foucault's observation that May '68 questioned politics in ways that weren't themselves inscribed into political theory. As Julie Stephens observes, it is a useful way of conceptualising a new language of protest that refused rigid distinctions and on which familiar paradigms of the '60s are founded: New Left/counterculture, activists/hippies, political/apolitical. ‘In short,' writes Stephens, ‘what was rejected was the "discipline" of politics' - doctrine, ideology, party line.i

To approach psychedelia through cyber-netics may bring back some of the strangeness and chaotic potential that the counterculture has lost along the way. The psychedelic is associated with an exuberant imagination in which the next moment, as with Bergson's durée, is incommensurable with the present one. Why, when we read its history, is psychedelia subject to the compulsive repetitions of a cultural memory that bleeds into the present and that we must push ahead of us? Why is it so difficult to leave Abbey Road and Fillmore West and meet, say, the The Psychedelic Aliens in Accra or Flower Travelling Band in Tokyo? Why are Huxley and Leary hailed like Columbus, when anybody can turn on? Why this monotonous insistence on origin when the psychedelic is - has the potential to become - a logic and an art of radical openness, reconstruction, and metamorphosis? There is a counter-intuitive inertia in the psychedelic, a reluctance to let go that tends to let imagination go to the dogs. 'Sex is boring', Foucault said. In the same way, drugs are boring.ii

It has long been a staple of the critical reception of the countercultural '60s that they form a continuation of Enlightenment paradigms. Today this genealogy can be revisited after the moment of a post-modern critique of the Enlightenment has passed, and the latter's values of tolerance, civic rights and political self-determination are now directly or indirectly cast into doubt by contemporary politics and economics. It is also worth noting that it is in relation to instrumental reason that a cybernetically inspired psychedelia is thus involved in a family argument with modernity's rationalist and scientifice episteme; something which opens it up to a post-humanist Enlight-enment. Psychedelia can perhaps be considered a deliberate continuation of the Enlightenment's incessant self-destruction, as Adorno and Horkheimer put it; a destruction undertaken by the counterculture in order to show how reason in the post-WWII era had failed historically, yet how it must be pursued in order to guarantee social freedoms. Of course, psychedelia cannot be called a cult of facts, and philosophy hardly played a role in it. But I would argue that an impulse to a radical Enlightenment can be detected here in the attempt to bring life back into reason; a reason that has not been formalized and instrumentalised, and whose goals therefore haven't become illusory. Thus the pleasure of audio feedback whine would be that of beating existing civilisation with its own weapons: rather than psychedelic - mind-manifesting - protest, a socio-delic critique that divorced technological and societal tendency.

Sound in the Paleo-Cybernetic Era

Apart from Luddite resistance against what Timothy Leary called a world full of stinking machines, Aquarian Arcadias were also conceived of with a view to embracing more sophisticated technology.iii For Gene Youngblood, author of Expanded Cinema (1970), cybernetic technology had opened up an evolutionary horizon in relation to which humankind still only found itself in a ‘paleo-cybernetic' era. Youngblood observed that ‘Mysticism is upon us: it arrives simultaneously from science and psilocybin.'iv However, cybernetic knowledge can also be considered as more reflexive mode through which the subculture can be seen to depart from mysticism and harmonic myth.

With feedback, media boundaries were transcended in the visual arts. Pioneering media artists such as Nam June Paik employed it as a distortion effect, and Hans Haacke's installations dealt with environmental feedback as participation, understood in terms of ‘agency conferred on your every action.'v Haacke used feedback in his 1968 installation Photo-Electric Viewer-Controlled Coordinate System, where the beholder's movements would turn light bulbs on and off by interacting with a grid of infrared beams. Haacke described this as, ‘Environmental feedback. Agency conferred on your every action. You're participating. You're making the art.' Haacke deconstructed this cybernetic position in a later work called Norbert. All Systems Go, (1971), in which he attempted to teach a Mynah bird named Norbert, after the cybernetics' founding father, to parrot the phrase ‘All systems go', in what appeared to be a parody of Norbert Wiener's optimistic feedback-steered path of progress. As an unintended twist on Haacke's satire, Norbert refused to comply with his instructions.

Feedback, of course, is a signature effect in acid rock, defined by Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead simply as ‘what you listen to when you are high on acid.' It was also used as a visual effect in posters where form is made to mutate through its repetition. But it was a less of a dynamic effect in graphic design than in real-time deployments in electronic media where it achieved its full potential. Thus feedback noise was a marker of the counterculture, but also represented a dep-arture from the harmonic, spectacular and style-oriented forms of psychedelic rock and visual production. To the artist Woody Vasulka, the West Coast psychedelic poster exemplifies a visuality that ‘gives the trip a handle' through certain recognisable styles; or simply becomes a counter-cultural form of advertising. The San Francisco Diggers, an activist network at the time, similarly criticised the counterculture for producing ‘bags for the identity-hungry to climb into.'vi

Anti-disciplinary feedback, on the other hand, resists identification and style because it breaks the mimetic mold. As we know from Jacques Attali, this is the nature of noise, its association with ‘the idea of the weapon, blasphemy, plague' and how it has been experienced as ‘destruction, disorder, dirt, pollution, and aggression against the code-structuring messages.'vii But as Steve Goodman dryly notes, many of these avant-gardist formulations of noise as a weapon in the war of perception ‘fail time and time again to impress.'viii Indeed, what is relevant here is noise in excess of itself as a perceived negativity.

Audio feedback is a loss of order, a turb-ulence that became a desired effect in acid rock, where musicians would amplify already amplified sound in order to produce distortions, or to ‘play' on or with the sound effect itself. It was typically used in controlled ways, to give the sound texture and spatial volume; that is, as a synaesthetic effect in which sound touches on space and tactility, nudging the whole system of the senses into play. To this end an arsenal of apparatuses was used which could manipulate electric sound, from fuzzboxes and flangers, to the Echogeräte that Krautrockers Guru Guru listed among their instruments. Jimi Hendrix, of course, excelled in overdriven sound, making frequent use of feedback as a colouring effect, as well as a way of building up an atonal climax at the end of gigs. To some, this qualifies him as a cybernetic musician, rather than a guitar god: he played from inside the machine.ix The ‘pure' or autonomous feedback noise belonged in the context of live music. Thus the band Red Krayola began their concerts with half an hour of feedback, The Grateful Dead devoted a brief section of their live shows to a feedback-driven composition, and many bands - including the Velvet Underground and The 13th Floor Elevators - would finish their gigs with their instruments leaning against the amps, playing on their own after the band members had left.x The instruments would ‘feedback forever, like they were alive', explains Lou Reed.xi

Circuit-bending acid rock feedback became a kind of sonic meta-strategy. As a disaster of melody it fulfilled negative characterisations of rock'n roll as ‘just noise', as the proverbial parental complaint goes, producing an anarchic sense of freedom for those who stayed and listened. Of his feedback-only double album from 1975, the conceptual apotheosis of experiments started with Velvet Underground in the 1960s, Lou Reed said, ‘Once you hear Metal Machine Music it frees you up. It's been done - now you can do anything.'xii A sonic Eden of electric force fields.

Other transgressions were also performed in this way. As a pure noise effect, feedback tended to subvert the individual band's particular sound. Even if the guitarist can attain some level of control of the feedback's frequency and amplitude (by ‘filtering' the feedback path with the strings, or manipulating it by shaking the instrument in front of the amplifier), the musician is reduced from being a prime mover to a listening agent in a soundscape in which intentionality and self-expression are dethroned. The feedback effect is, in this way, comparable to those dialectical visual art forms of the 1960s - Concrete Poetry and Destruction Art, Earth Art and Conceptualism - that were characterised by anonymity, randomness and processual automation.

The Organisation of Living Systems

Cybernetics operates with two definitions of feedback. The one describes the preservation of circulation in a system by aiming to maintain equilibrium through maximum adaptability. This is negative feedback as it works in the thermostat, for example, that functions through a non-linear (hence negative) causal relation. Positive feedback, on the other hand, is also typically conceived as non-linear, but it works against adaptability. To attain positive feedback, one quite simply removes the control functions that are otherwise located where the information loop would meet itself to control its dynamic behaviour. Manuel De Landa:

The turbulent dynamics behind an explosion are the clearest example of a system governed by positive feedback. In this case the loop is established between the explosive substance and its temperature. The velocity of an explosion is often determined by the intensity of its temperature (the hotter the faster), but because the explosion itself generates heat, the process is self-accelerating. Unlike the thermostat, where the arrangement helps to keep temperature under control, here positive feedback forces temperature to go out of control.xiii

The principal characteristic of negative feedback in the thermostat is its homogenising effect; deviations are filtered and eliminated. This is unlike positive feedback that, as De Landa explains, ‘tends to increase heterogeneity, as small original differences are amplified by the loop into large discrepancies.'xiv

Clearly audio feedback's explosive, increased heterogeneity is an example of positive feedback. But because of its self-generative properties it can also be described as a kind of organism. So beyond being noise, anti-disciplinary feedback is also autopoietic - meaning self-creating, self-producing. This is the term coined by biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela in their work Autopoeiesis and Cognition (1973). Autopoietic organisation is here defined as ‘necessary and sufficient to characterise the organisation of living systems.'xv Thus machinic and organismic definitions of life overlap in autopoiesis, as do the individual machine or organism and its larger ecology. Maturana and Varela consider cognition to be ‘effective action, an action that will enable a living being to continue its existence in a definite environment as it brings forth the world. Nothing more, nothing less.' Thus Maturana and Varela hold that learning is ecological, defined by proportionality and correspondence with a changing environment.xvi By contrast, Norbert Wiener's idea about learning, which he connects directly to feedback phenomena, is internal to the system, characterised by the machine's ability to change its performance.xvii In other words: the audio feedback, whether intentional or unintentional, is the sound of the amplifying system cognising or learning, and coming alive (or ‘learning about learning', to use W. Grey Walter's phrase). xviii

In his novel about Ken Kesey's LSD-activism, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), Tom Wolfe describes feedback as the production of a total environment, a nervous system that is not the property of the individual subject. Here Ken Kesey and his group of Merry Pranksters prepare their school bus for a stateside trip which took their acid tests on the road, ‘barrelling across America with the microphone picking it all up.'xix

Sandy went to work on the wiring and rigged up a system with which they could broadcast from inside the bus, with tapes or over microphones, and it would blast outside over powerful speakers on top of the bus. There were also microphones outside that would pick up sounds along the road and broadcast them inside the bus. There was also a sound system inside the bus so you could broadcast to one another over the roar of the engine and the road. You could also broadcast over a tape mechanism so that you said something, then heard your own voice a second later in variable lag and could rap off of that if you wanted to. Or you could put on earphones and rap simultaneously off sounds from outside, coming in one ear, and sounds from inside, your own sounds, coming in the other ear. There was going to be no goddamn sound on that whole trip, outside the bus, inside the bus, or inside your own freaking larynx, that you couldn't tune in on and rap off of.xx

The very movement of the Merry Prankster bus became an all encompassing, ever renewing, mobile loop of sound-events, synchronising everybody on and off the bus in the ‘Now Trip'. Their audio system would hook up several vibratory surfaces and structures: the inside and outside of the bus, the space between people, and the insides of their bodies, all of which would be compressed and stretched and fed back to the space they passed through. The result was phantasmagoric, understood ecologically or topo-graphically rather than as something spectral. For Gilles Deleuze, the phantasm is an effect that ‘transcends inside and outside, since its topo-logical property is to bring its internal and external sides into contact, in order for them to unfold onto a single side.'xxi In such phantasmagorical sound, different sources and manifestations of sound unfold side by side, rubbing against each other in a dense materiality.xxii

Questions of control and counter-conditioning are not far away in the Merry Pranksters sound ecology. William Burroughs conceived of a viral version of feedback that he called playback: his idea was to play incongruous, out-of-place tape recordings in public spaces in order to break mental lines of association laid down by mass media. He saw this version of feedback as a ‘biological weapon', a re-coding of psychological patterning from which a psycho-acoustic virus would emerge. But Burroughs' playback is again close to the avant-garde idea of noise as weapon, and it may be worthwhile approaching the ‘low-church psychedelic'of Kesey and the Pranksters with the sophistication of contemporary theory. Jean-Luc Nancy argues that in the sonorous register, sensing offers itself as an open structure that is ‘spaced and spacing' in the movement of an infinite referral that puts subjectivity into play. In his own words,

When one is listening, one is on the lookout for a subject, something [...] that identifies itself by resonating from self to self, in itself and for itself, hence outside of itself, at once the same and other than itself. One in the echo of the other, and this echo is like the very sound of its sense.xxiii

Spaced-out sound that addresses itself by sending itself back to itself opens up the phenomenology of listening until individual and collective subjectivity is fluid.

To be listening is thus to enter into tension and to be on the lookout for a relation to self: not, it should be emphasised, a relationship to ‘me' (the supposedly given subject), or to the ‘self' of the other (...), but to a relationship in self, so to speak, as it forms a ‘self' or a ‘to itself' in general, and if something like that ever does reach the end of its formation.xxiv

The feedback commune is truly a whatever community as it passes through space that is turned inside out.

Events-Effects in Aion

Audio feedback also generates unstable temporal effects. According to Wiener, feedback is the ability to adjust future conduct by past performance. We know that the cause-and-effect relation in negative feedback forms a closed loop in a circular causality, but what about the positive feedback? Here future conduct adjusts past performance as the feedback continuously re-generates the input signal. We can say with Deleuze that the audio feedback is the sound of the event in its own time, Aion, an ‘essentially unlimited past and future.'xxv Aion is the time of ‘events-effects', and it ‘retreats and advances in two directions at once, being the perpetual object of a double question: what is going to happen? What has just happened?'xxviIn a Deleuzian perspective, then, the audio feedback is not a loop but a ‘straight line and an empty form', a process of unfolding that has an ‘agonizing aspect'. The French word sens can mean either meaning or direction, and the audio feedback is hence not without direction and meaning, but rather producing a double direction, double sens; a simultaneity that exerts a contradictory, agonising pull on the listener and her temporal orientation.

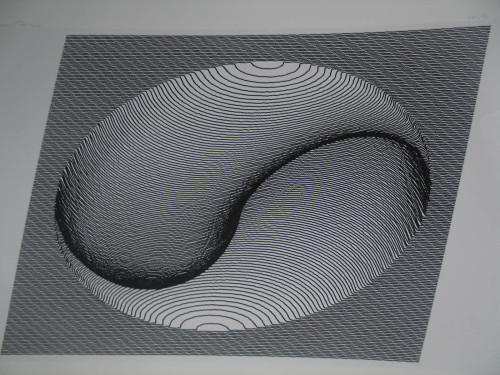

Image: Lithograph by Sture Johannesson

The paradoxical nature of the effect is set to work by an initiator or effector that withdraws in order to let it unfold. The effect can be self-generating to the point that it comes alive and thereby it can become something as strange as an autonomous supplement: it is supplementary to its cause or its initiator, yet free, acting on its own. In this way effects flicker between essence and attribute, control and chance, purpose and redundance, nature and artificiality. This instability is in itself life affirming and life generating, a machinic vitalism that can be understood in terms of Norbert Wiener's notion of irritability as a fundamental life phenomenon: a lower limit of stimulation, friction and excitement, or other ways in which tolerance is pushed and the general equilibrium disturbed.xxvii

We can speculate - anachronistically - that the psychedelic use of feedback testifies to the subculture's Wille zur Wirkung (or ‘will to effect'), to use the delightful concept of the philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, writing in Kalligone (1800). In this work, Herder took Kant's aesthetics to task for spreading a ‘transcendental flu' among the young and he instead emphasises the role of the senses in the aesthetic experience with regard to a fusion of spirit and matter that strengthens existence. In this context, ‘will' should not be understood as muscular intentionality but as a potentially variable relation of forces, including external forces outside of the subject's control. With a concept that resonates with psychedelic art forms, Herder predicates sound on elasticity, which he takes to indicate the refinement of hearing, and the way that it is receptive to the subtlest of impressions. Through their sound, succession and rhythm (Klang, Gang und Rhythmus), tones are ‘vibrations [...] of our sensations'.xxviii In sound (or Klang), not only the ear, but the entire inside of the moved body speaks out. This bodily vibration - based in the way all bodies are more or less elastic - calls ‘the voice of all moving bodies forth from within them [...] loudly or softly proclaiming the excited state of their powers to other harmonic beings'xxix Through the ear's receptivity and through sound's bodily reverberation, an intensive or more deeply sensed truth can be experienced, in an immersion in outer reality. Herder connects hearing's elasticity to a primary truth in invisible and tactile worlds (with sculpture as hearing's privileged equivalent, rather than the deceit of painting's decoration of surface). Accordingly, true perception is like the soul touching in the dark, and hearing's capacity for sympathetic sensation is at its strongest when it is set in vibration by, and resonates with a voice from a similar being; so Herder has it that it is the human voice that touches the human being most deeply.xxx The intention to put subjects, or beings, in sympathetic vibration with each other is the Wille zur Wirkung, the will to effect. In short, good vibes.

Herder's rejection of the mind-body distinction is symptomatic of the way sound escapes the virtual-material divide, and the properties it has for bringing forth new worlds. Thus the concept of feedback comprises transformative as well as stabilising functions. It is a concept that can rehearse stimulus and response in order to maintain a system's ability for recognising itself through already established codes or procedures, but it can also push the processing of signals in a system to the point where they may oscillate out of control and possibly end up destroying the system-or start creating new life. It is important to an understanding of psychedelic art and counterculture to recognise that it articulated a form of critique by appropriating a trope meant for system preservation. Of course it is unimaginable for anti-disciplinary feedback to have existed on its own, without being embedded in the melodic acid rock and the culture industry, but it prevails as a highly conceptualised and experimental ‘will to effect'. It is the story of how the electric circuit produced sound by itself, and hence began to learn and to generate sonic organisms and autonomous nervous systems - something that it wasn't supposed to do at all.

Lars Bang Larsen <larsbanglarsen AT yahoo.com> is an art historian, curator and writer. He recently curated A History of Irritated Material at Raven Row, London and is writing a P.h.D. on '60s psychedelic art and culture at the University of Copenhagen

Info

Signal: Noise was a two day event at the Showroom gallery, London, 13-14 January, http://www.theshowroom.org/research.html?id=161,363

Footnotes

iJulie Stephens, Anti-Disciplinary Protest. Sixties Radicalism and Postmodernism, Cambridge University Press 1998, p.23.

iiMichel Foucault, On the Genealogy of Ethics: An Overview of a Work in Progress, (1983), quoted from Paul Rabinow, Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984. Ethics, vol. 1, Penguin, London 1997, p.253.

iiiGene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema, New York: Dutton & Co., 1970, pp.3-4. The counter-culture's fascination with cybernetics thus predates Leary's post-psychedelic writings on artificial intelligence in the 1980s. Inconsistent with his attacks against stinking machines, he exalts the turned-on human brain in his 1966 book Psychedelic Prayers After the Tao Te Ching as a ‘13-billion cell computer'.

ivYoungblood, op.cit., p.138.

vHans Haacke, ‘Photo-Electric Viewer-Controlled Coordinate System' (1968). Quoted from Luke Skrebowski: ‘All Systems Go: Recovering Hans Haacke's Systems Art', Grey Room No. 30, Massachusetts: MIT Press 2008.

viDiggers.org and Woody Vasulka, in conversation, Santa Fe June 2007 http://www.diggers.org

viiJacques Attali, Noise, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985, pp.343-344.

viiiSteve Goodman, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect and the Ecology of Fear, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2010, p.7.

ixBoth the artist Robert Horvitz and the film-maker Neville D'Almeida have confirmed this in private conversations.

x See for example Keven McAlester's You're Gonna Miss Me: A Film About Roky Erickson, Sobriquet Productions, 2007. The first use of feedback on a commercial recording is probably the phasing intro to The Beatles' ‘I Feel Fine' from 1964. The same year the composer Robert Ashley brought feedback effects to avant-garde prominence in his 20 minutes long composition The Wolfman Tape. This consisted of a high frequency ‘full room feedback': The sound equip-ment would be tuned to a pitch where it would encompass the entire space and the listeners in it. A purely spatial feedback, Ashley says, ‘allows even the smallest sound at the microphone to take on the illusion of moving around the room, depending on frequency and other aspects of the microphone sound.' This is unlike the feedback in rock music that is ‘localised to the guitar amp and deafens only the guitar player.' http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/cutandsplice/wolfman.shtml#top

xi David Fricke, Metal Machine Music, liner notes for the Buddha Records CD re-issue (2000).

xii David Fricke, Metal Machine Music, ibid.

xiii Manuel de Landa, A Thousand Years of Non-Linear History, New York: Zone Books, 1997, p.68.

xiv Ibid.

xv Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela, Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living, Dordrecht and London: Reidel, 1980, p. 82.

xvi Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela, The Tree of Knowledge, Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1992 (1987), p.170.

xvii Wiener writes, ‘Feedback is a method of controlling a system by reinserting into it the results of its past performance. [...] if the information which proceeds backward from the performance is able to change the general method and pattern of performance, we have a process which may well be called learning. (Norbert Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings. P.15.)

xviii Chapter 6 of The Living Brain is called ‘Learning About Learning', pp.119-38.

xix Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, p.66. London: Black Swan 1989 (1968).

xx Ibid., p.80.

xxi Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, London: Continuum, 2004 (1969), p.242.

xxii For example ‘Feedback from Watergate to the Garden of Eden', in William S. Burrough's Electronic Revolution. Bonn Expanded Media Editions, 2001 (1970). Friedrich Kittler makes a similar point, asserting that if ‘control, or as engineers say, negative feedback, is the key to power in this century, then fighting that power requires positive feedback. Create endless feedback loops until VHF or stereo, tape deck or scrambler, the whole array of world war army equipment produces wild oscillaitons. Play to the powers that be their own melody.' Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford University Press 1999, p. 110.

xxii Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening, Fordham University Press, 2007 (2002), p.9. Nancy's italics.

xxiv Ibid., p. 12. Nancy's italics.

xxvDeleuze, op. cit., p.72.

xxvi Op. cit., p.73.

xxvii Norbet Wiener, Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (2nd edition). Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1965 (1948/1961), p.11.

xxviii J.G. Herder, Sämtliche Werke, 1877-1913, Vol. 22, p.326. Quoted from Friedrich Ostermann in, Die Idee des Schöpferischen In Herders Kalligone, Bern und München: Francke Verlag, 1968, p.56. My translations.

xxix Ibid., p.18.

xxx Ibid., p.19.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com