Altermodern: Movement or Marketing?

Is the concept of ‘The Altermodern’, which organises Nicholas Bourriaud’s Spring art blockbuster at Tate Britain, anything more than re-spun curatorial spin? – asks Nickolas Lambrianou

To coin a new term and have it, if not exactly universally established, then at least acknowledged in the already overcrowded vocabulary of contemporary art speak might be ambition enough for most critics. Indeed, to offer a name for a movement, a group or a new ‘spirit’ in art is something that most writers concerned with contemporary art would be very wary of doing, given that we live in an irreversibly pluralist age. Writer and übercurator Nicolas Bourriaud appears to know no fear, however, when it comes to generating terminology. Indeed, not only did he coin many of the most recent terms for the type of practices predominant among younger artists over the past two decades (‘relational aesthetics’, ‘postproduction’, ‘semionaut’), but now he appears to actually want to coin a term for the age that we – the artists, the theorists and the audience – find ourselves in. It’s as if Greenberg, not content with bestowing on the world a grand definition of modernist painting, then wanted to actually rechristen modernity too. Nonetheless, Bourriaud wants to give us ‘The Altermodern’, an alternative reading of the contemporary, global situation as it effects both the production and reception of whatever is left of the ‘avant garde’ in art.

Image: Entry to Altermodern, 2009

Bourriaud launches the term via a rebranding of the fourth Tate Triennial for which he is this year’s guest curator. But also with a book, a series of events before, during and after the exhibition, and even a manifesto, published on the Tate website. Whether this latter is a heartfelt or ironic return to the most typically modernist, proclamatory form we may never know, but nonetheless Bourriaud declares immediately that ‘postmodernism is dead’. One can almost hear the cheers rise across the land, or at least from Hoxton Square to Vyner Street. But if the Altermodern signals for Bourriaud an end to the terminological confusion and tired debates of postmodernism, then that which follows it – at least the version sketched out on the Tate’s ‘Explain Altermodern’ internet manifesto – looks oddly familiar:

Increased communication, travel and migration are affecting the way we live.

Our daily lives consist of journeys in a chaotic and teeming universe.[...]Today’s art explores the bonds that text and image, time and space, weave between themselves.

Artists are responding to a new globalised perception. They traverse a cultural landscape saturated with signs and create new pathways between multiple formats of expression and communication.

Our expectations, it seems, may have been falsely raised: Altermodernism appears to be postmodernism regurgitated, rebranded as a bullet-point manifesto. To be fair to Bourriaud, the idea is fleshed out some more in his introductory essay to the book accompanying the show, where it is defined more precisely as a form of radical cultural decentring (‘the artist turns nomad’) aligned with a wilful rejection of what he reads to be the ‘mournful’ condition of a certain mode of postmodernism (the one that mourns the failed utopias and lost discourses of high modernity).i Free of the binds of both modernist and postmodernist historical periodisation, Bourriaud’s artist-nomad is free to travel not only across space and time but among the fragmentary ‘signs’ encountered in their historical and global meandering. Surely, he seems to be saying, we are now well and truly post whatever postmodernism was, and we should celebrate the creatively transient freedom offered by this ‘alter’ (read: ‘other’) modernity? Join the Altermodern revolution, Bourriaud seems to be saying, you have nothing to lose but your aesthetic and theoretical chains: postmodernity and all its tired debates.

Nonetheless, one might say that Bourriaud is quite right to point out that postmodernism as a term was fundamentally flawed – Lyotard for example was regretful of the misunderstandings it generated from the moment he coined it – and he is certainly perceptive enough to realise that there is a need for a redefinition of whatever form of modernity ‘we’ now find ourselves in. But Bourriaud is also capitalising on a generational desire to move beyond what has become a rather familiar series of debates in art theory and, in doing so, appears to be moving beyond even those ideas initiated by himself. Yet is this a real development, or merely a rebranding of relational aesthetics, postproduction and so on? His claim for the exhibition might lead us to anticipate a real change from relational aesthetic interactivity to something like Altermodern narrativity:

The exhibition assembles works whose compositional principle relies on a chain of elements: the work tends to become a dynamic structure that generates the forms before, during and after its production. These forms deliver narratives, the narratives of their very own production, but also their distribution and the mental journey that encompasses them.ii

Are these grand claims made for Altermodernity apparent in the exhibition itself? The scale is certainly impressive – 28 artists taking over the Duveen galleries and much of the rest of Tate Britain – and the selection criteria have been extended to include any artist who works, rather than resides, in the UK. Presumably this has to do with ‘residence’ being much too tied up with old modernist ideals such as nationalism, but it also means that stateless auto-destructivist Gustave Metzger can be included alongside young graduates of British art schools. The first work one encounters is Subodh Gupta’s Line of Control (2008), a mushroom cloud made of stainless steel utensils, extending to the full height of the Duveen Gallery. This seems to set the tone for other technically ambitious works such as Ruth Ewan’s Squeezebox Jukebox (2009), a giant Italian accordion playing traditional protest songs, and Matthew Darbyshire’s Palac (2009), an ambitious Day-Glo architectural installation that mocks the cultural pretensions of civic architecture.

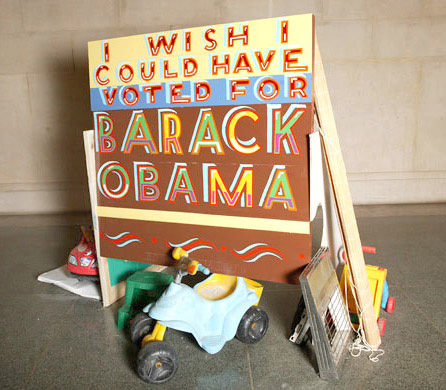

Image: Bob and Roberta Smith, Off Voice Fly Tip, 2009

Bob and Roberta Smith’s Off Voice Fly Tip (2009) breaks this run of technically proficient sculptural work with a scattered, continuously changing installation of hand painted wooden signs which are interspersed with found items such as discarded children’s tricycles. The texts are all based on conversations that Bob and Roberta plan to have with Nicolas Bourriaud on the 12 successive Fridays during the course of the exhibition, or, when the Smiths fail to catch the international jet-setting curator, other idle thoughts about the ‘oligarchic’ nature of the art world and what it means to be an outsider in relation to it. As such, Bob and Roberta demonstrate an ambivalence typical of the not-quite successful artist in the face of the current art world – relying on an improvised, do-it-yourself wit allied to a keen sense of their exclusion from the world which is nonetheless repeatedly the subject of their art. The installation has a melancholy feel which may be indicative of this ambivalent spirit, like the experience of the kid who turned up for the fun fair just after it had packed up and moved on, but still plays amongst the remnants.

In one text, the artist-outsider hears of a connection between their maverick guiding spirit (Mark E. Smith) and the big-deal curator, which beggars belief. All Bob and Roberta can do is, once again, transform this dialogue back into a work of art: ‘Someone told me that Nicolas Bourriaud had played drums in The Fall. I asked if this was true? He said “no not really, just two songs when I was a kid in London in the late 1970s”.’ Given the staggering number of different drummers that Mark E. Smith has employed over the years, it is perhaps only a matter of statistical probability that one of them would later turn out to be a contemporary art big-shot. Nonetheless, it reinforces the feeling that some people (sharp suited, well connected, theory literate curators perhaps) are born to be successful, whilst others try to make success out of the art of failing to be successful. Which begs, of the latter, the question of what their art will be about once they have jumped on the Altermodern bandwagon.

Image: Walead Beshty, FedEx Sculptures, 2009

This is not Mike Nelson’s dilemma. His impressive The Projection Room (Triple Bluff Canyon) (2004) is at once a film piece projected onto the gallery wall and an installation that sits, self-contained, in the centre of the Duveen gallery. You cannot enter the projection ‘room’ itself (unlike his spaces, which invite you to enter by crawling through holes in the wall for example), but looking into it, one would not be sure that anyone would want to either. This is a typically creepy Nelson space, complete with what by now are his trademark paraphernalia: clown masks, workbenches, ominous looking tools and improvised equipment, plus well thumbed copies of National Geographic and other, more arcane, works of literature. It’s the secret den of a particularly well read and widely travelled serial killer, or some other alienated loner. But, in opposition to Bob and Roberta’s folksy witticism, this implies a filmic, foreboding narrative.

If, at this point, we are beginning to wonder if Altermodernism has a signature style, it might be found either in work like Nelson’s or in Francis Ackerman’s installations of large relief canvasses and architectural constructions such as <<Gateway>>-Getaway (2008-09) included here. This is a knowingly gaudy work, and one gets the sense that this is a ‘post-conceptual’ abstract painter who has cynically added a few relationally aesthetic touches to the installation such as piles of luggage tags and sound elements fed though headphones. It’s as if there is an anxiety about mere painting in itself not being quite Altermodern enough. One might have similar reservations about Charles Avery’s Aleph Null Head (2008) and Installation of Drawings (2009). His skilful draughtsmanship uses a knowingly anachronistic style to serve a pseudo-anthropological narrative of cartoon explorers discovering mysterious artefacts. This is interesting art, a postcolonial mockery of our received ideas of ‘primitivism’, but one has the uneasy feeling that it is popular because of its old-fashioned technical dexterity, rather than any specifically Altermodernist content that the artist might be trying to convey.

For me, it is three other artists who really steal the show, largely because they don’t rely too much on relationally aesthetic mannerisms but wilfully re-examine modernist debates from other angles. Walead Beshty’s shattered glass cubes are, in simple terms, the record of their own international transportation. Glass cubes of the same dimensions are packed in FedEx boxes and shipped to the gallery in which the artist is due to exhibit. Inevitably damaged in transport, they are then displayed on the cases in which they were packed. As the material record of their own journey from A to B, they are in a certain sense as modernist as a Jackson Pollock. Yet they can equally be read as an allegory of the transnational ‘FedEx’ culture of the contemporary art world. The idea of the ‘artist as international traveller’ is achieved with more subtlety in this piece than elsewhere in the exhibition.

Image: Simon Starling, Three White Desks, 2008-9

Another set of once pristine objects transformed by their own journey from one place to another, Simon Starling’s Three White Desks (2008-09), use the difficult relationship between ‘fine’ art and ‘applied’ design to explore questions of transmission, replication and the suppressed roots of modernist activity. In the 1930s Francis Bacon, then working as an interior designer, designed and had made a sleek international-style writing desk for the Australian writer Patrick White. However, White left the original Bacon desk behind in England when he returned to Australia in 1947, and had a joiner recreate the desk there. Half a century later, Starling has commissioned three separate cabinet makers to recreate the desk, the first from a high resolution digital reproduction of a photograph of the 1947 copy, and then, in turn, from lower resolution digital images of the modern copies, in a sort of prolonged historical game of Chinese whispers. This amount of craft and time invested in recreating what seems like a mere historical footnote to Bacon’s career (and one which Bacon himself attempted to obliterate when he destroyed all his early interior design work after becoming a ‘serious’ painter), may seem like a piece of Altermodern pseudo-historical whimsy. However, it makes a broader point about the way we choose to read the narratives of modernism itself. Starling uncovers the unresolved tensions that neither postmodernism nor Altermodernism seem to have overcome, and which Bacon’s own split personality seems to personify; a tension between order and chaos, expressed as the utopian whiteness of 1930s interior design versus the grey-blackness of 1950s gritty realism that underpinned Bacon’s subsequent work. The desk is thus the perfect symbol of the contradictions at the heart of modernist history – it is at once a historical readymade to be endlessly repeated (just as Duchamp enjoyed the absurdity of his own ‘original’ readymades being reproduced), yet one that marks the moment where early modernist craft was discarded in favour of high modernist expression. Furthermore, as both a place of study and the lost object of Bacon’s studio, it also stands for the investigative nature of contemporary art practice, the sleuth’s search for origins (for historical truth) in an age where all hope of originality, authenticity and truth has supposedly been lost. Yes, the anxiety over originality is now itself unoriginal, a tired postmodern debate, but Starling’s work at least gives us a glimpse of that alternative modernity that the Altermodern claims to represent.

Nathaniel Mellor’s Giantbum (2009) similarly plays with narratives within narratives, and explores the iterative, mediated aspects of performance, installation and film. Giantbum is both a film and a labyrinth, in which appear two recorded versions of the same ribald, absurdist script. The first is a sort of (staged?) dress rehearsal in which the actors read the parts in a corridor, looking slightly nervous and awkward as if they are aware that what they are doing is about to become ‘Art’ rather than theatre. The second version is more polished, but the use of deliberately amateurish special effects and costumes makes one aware that Mellor knows his Brecht even as his script involves references to Rabelais and Pasolini’s Salo. At the end of the labyrinth, the fakery is taken to a different technological level, and we are confronted by three hyper-realistic animatronic recreations of the face of the main character (‘The Father’), mumbling and moaning, the technological apparatus visible behind their ‘flesh’ making them even more uncanny. (Apparently the invigilators have learnt to situate themselves out of view of these heads, as many were complaining of nightmares.) The scatological mutterings of ‘The Father’, obsessed with regurgitation and coprophilia, turn out to be less about auto-regeneration than evidence of unacknowledged entropy. It is tempting to see this as a comment on the condition of contemporary artspeak. Indeed, it may come as no surprise that young artists, after being bombarded at art school with Battaille and Lacan, should want to produce work that mocks the arcane, fragmentary pretensions of ‘theory’. But could we have expected them to become the best placed critics of the pseudo-philosophy of contemporary art criticism itself?

Image: Nathaniel Mellor's animatronic recreation of 'The Father' from Giantbum, 2009

Overall, however, there is little evidence of the real interactivity which was a signature of relational aesthetics. For all the post-postmodernist radicalism of the concept then, the exhibition itself is neither Dada-Messe nor post-conceptualist curatorial mix-up. There are ‘events’ and performances to be sure, but these are not a core part of the show and there is little evidence of that supposedly ‘democratic’ interactivity that was a key characteristic of relational aesthetics. There is no shifting of boundaries between artist and audience, and little undermining of any other curatorial conventions. Where there is collaboration or interaction, it is only in the ‘platforms’ mediated by Bourriaud himself and documented in the catalogue. The novelty claimed for the concept is not, therefore, matched by curatorial innovation. This discrepancy between label and content – between advertisement and product – aligns Altermodern with the very commodity culture which one might assume critical art to be hostile towards. One could argue that Altermodern is the branding – the unique selling point – of a familiar curatorial convention, a straightforward snapshot of what some artists are up to now. This criticism has also been applied to relational aesthetics, which its rebranding as Altermodernism does nothing to redress. All this talk of ‘platforms’, remixing and dialogue unconsciously parrots, rather than critically attacks, the language of neoliberal business culture that it has traditionally been the job of critical art to stand against.

And so there is a serious flaw here. The Altermodern calls for experimentation over object, the particular over the universal, dialogue over diktat, but where does the discursive power lie? Is the term a useful, coherent and critically productive way of describing some new ‘direction’ in modern art, or – worst case scenario – is the work selected only for its ability to serve or illustrate the concept? Duchamp once said (according to übercurator Hans Ulrich Obrist) ‘in the organisation of an exhibition, never let the works get in the way’.iii But surely Duchamp was knowingly undermining the idea of the sovereign art object, and not willing the day when artworks would serve only as the illustrative appendices to a critic’s new idea. Only some of the artists are brave and honest enough, in their published statements, to call into question the usefulness of the term Altermodern, or the presumptions underlying it. In the case of the single artist – Spartacus Chetwynd – willing to sign up to the Altermodern ideal, it is still only with a less than wholehearted ‘why not?’. But do young artists have a choice? Is the condition of the Altermodern such that young artists are now really and finally free of the contradictions of the postmodern, or are the terms of the debate still set elsewhere, by those with the power over contemporary artspeak?

Nickolas Lambrianou <nlambrianou AT yahoo.co.uk> is a writer and lecturer specialising in the history and theory of modern art. His work has appeared in Radical Philosophy and Contemporary Magazine and recent publications include ‘The Subject of Immigration’ in Witness: Memory, Representation and the Media in Question, edited by Ulrik Ekman and Frederik Tygstrup (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2008)

Footnotes

i Nicolas Bourriaud (ed.), Altermodern: Tate Triennial 2009, Tate, 2009, p.24.

ii Ibid., p.13-14.

iii Hans Ulrich Obrist, A Brief History of Curating, JRP Ringier, 2008, p.10.

Info

Altermodern: Tate Triennial, Tate Britain, London, 3 February - 26 April 2009, http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/altermodern/

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com