John Cayley on poetry, the alphabet and the future of programmatrons

Text is the Net's supreme structuring principle. It also creates its destructive elements - its weeds, moles, acidbaths and bombs.In the age of multimedia convergence, what is there left for text to teach us?

Text made the Net - made it possible, makes it now and for the time being. Text constitutes and encodes the Net, in major part, because text was 'digital' avant la lettre or rather, because of the letter. Once linguistic inscription had been encoded in a small character set (1700-1500 BCE in all but the Chinese culture-sphere), an important field of cultural production was already digitised. Literature was transcribed in a medium that is structured in a managable number of discrete objects. It is divisible into well-understood units down to an elementary level, and so easily editable. Moreover, it is editable in such a way that, after redrafting, the fractures and joins of the editing process may be made invisible. These are all features of so-called 'digital' production - now being applied, in particular, to audio-visual material - which are perceived as novel, the 'new' of new media. In fact, they are quite good examples of features found elsewhere in the culture, migrating from literature to the disciplines of image, sound, kinetics, etc., for reasons which are chiefly technical and logistic.

Text made the Net - made it possible, makes it now and for the time being. Text constitutes and encodes the Net, in major part, because text was 'digital' avant la lettre or rather, because of the letter. Once linguistic inscription had been encoded in a small character set (1700-1500 BCE in all but the Chinese culture-sphere), an important field of cultural production was already digitised. Literature was transcribed in a medium that is structured in a managable number of discrete objects. It is divisible into well-understood units down to an elementary level, and so easily editable. Moreover, it is editable in such a way that, after redrafting, the fractures and joins of the editing process may be made invisible. These are all features of so-called 'digital' production - now being applied, in particular, to audio-visual material - which are perceived as novel, the 'new' of new media. In fact, they are quite good examples of features found elsewhere in the culture, migrating from literature to the disciplines of image, sound, kinetics, etc., for reasons which are chiefly technical and logistic.

Particularly since the emergence of the codex or book format, literature has also been randomly accessible - including through non-linear links in the form of indexes, cross-references, tables of contents and so on. When computing machines came to be appreciated as more generalised Turing machines, or 'programmatons' (as they should, more properly, be known), our traditions of writing were surprisingly well-adapted. This is not to say that alphabetic transcription is essentially the same as binary representation. However, alphabetic writing already had digital characteristics (as I've said) and, more importantly for the development from 'computing' - calculating projectile and missile trajectories - to net art, the alphabet allowed relatively easy encoding of language-as-text, because of the relatively small number of transcription elements or letters.

Thus, even within the much lower bandwidths then available, significant quantities of (human-readable) symbolic representation could be transcribed and manipulated, all thanks to our 'byte-sized' alphabet and its particular traditions of literacy. In recent years, as the programmatons were networked, it was the same low-bandwidth/high-significance textual medium which enabled the net first to proliferate and then to set its rhizomes in the mulch of Media and popular culture.

It is an irony of our so-called digital age that the first digital medium to gain general currency - written text - constitutes not only the recent piratical pseudo-novelties of the net but also the established tradition of literature. The art of letters is still our preferred and privileged institution of cultural authority, and this 'art' and its criticism continues to be dominated by the integral, monologic 'voices' of master (sic) authors, to a much greater extent than is the case in, say, visual or even cinematic art. Text was always a medium perfectly adapted for the inherently (post)modernist experiments of collage, intercutting and creative plagiarism, ideal for the development of sampling (in the musical sense), framing and linking. All of these techniques might be demonstrated in, for example, the divinely authoritative field of Biblical criticism. However, these literacy-enabled rhetorical technologies remain marginal to literature-as-art, which we still expect to be 'authored' and 'original.' Following the extreme but indicative Biblical example, the Bible's radical collage is recast as revelation, direct from the horse's mouth of the ultimate monologist. Meanwhile, on the other hand, would-be canonical authors have been less than marginally active in the reconfiguration of a delivery medium (the Net) which is founded on their pretended compositional medium (text).

Today the Net is seen to represent an 'advanced' version of literacy — 'late literacy' (Jay Bolter) or 'post-literacy' (passim. in the Media) or even (proto-) 'electracy' (Gregory Ulmer). Yet this pop, literary avant-gardism has been achieved largely without the involvement or intervention of 'high art' textual practitioners (let's call them 'poets'). The critical perception of net literacy as 'advanced' is made explicit in the theoretical claims of the hypertext research community, where hypertext practice is proposed as a privileged instantiation of post-structuralist critical theory or even as its objective correlative. However, the critical theory in question was developed as a critique of the literary tradition, prior to the implementation of networked and link-node text. The majority of the subversive tropes and figures of electronic text - intertextuality, non-linearity, the 'writerly' text (Barthes, 1973!), the nomadic reader and problematised author - are, arguably, functions of the digital characteristics of writing, regardless of delivery medium (see: Espen Aarseth, Cybertext, Baltimore, John Hopkins 1997). These tropes and figures were latent in literacy and not established by the 'advances' of hypertext. The critiques of structuralism and post-structuralism were precisely designed to show how, for example, the supposed voice of the author was a cultural construct, by no means implied by any essential characteristics of writing. Rather, writing itself - long before its translation to node-link webs - subverted these constructions, exposed them as intertextual, non-linear, fragmentary, of problematic origin and reception.

The critical perception of net literacy as 'advanced' is made explicit in the theoretical claims of the hypertext research community, where hypertext practice is proposed as a privileged instantiation of post-structuralist critical theory or even as its objective correlative. However, the critical theory in question was developed as a critique of the literary tradition, prior to the implementation of networked and link-node text. The majority of the subversive tropes and figures of electronic text - intertextuality, non-linearity, the 'writerly' text (Barthes, 1973!), the nomadic reader and problematised author - are, arguably, functions of the digital characteristics of writing, regardless of delivery medium (see: Espen Aarseth, Cybertext, Baltimore, John Hopkins 1997). These tropes and figures were latent in literacy and not established by the 'advances' of hypertext. The critiques of structuralism and post-structuralism were precisely designed to show how, for example, the supposed voice of the author was a cultural construct, by no means implied by any essential characteristics of writing. Rather, writing itself - long before its translation to node-link webs - subverted these constructions, exposed them as intertextual, non-linear, fragmentary, of problematic origin and reception.

The adoption and popularisation 'overnight' of globally-linked pages and fragments can be seen as evidence of the predisposition of text to what the hypertext community calls 'advanced' or 'late' literacy; not, that is, a function of hypertextual advances. Meanwhile, every net-person and artist takes writing spaces and (click-)linking for granted. They are here today and accessible to use, regardless of their pedigree. But they are here and accessible, primarily, I argue, because the digital aspects of textuality were and are already familiar, introduced by the problematic dynamics of writing itself.

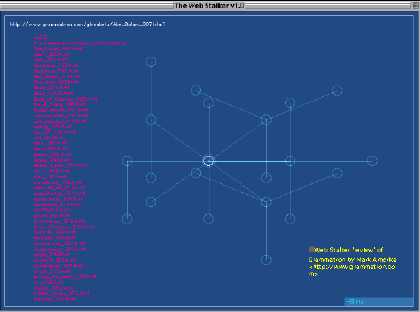

On the other hand, as I've mentioned, these developments have taken place largely without the engagement of poets, for another set of contingent reasons. In the first place there are the failures, luddite blindnesses, magisterial vanities and general bankruptcies of mainstream poetry. How many of you really want to read html versionings of laureate-Hughes-Nobel-Heaney-work in between visits to www.jodi.org? And you're probably only slightly more sympathetic to the author-indulgent cyberBeat world of Grammatron (see the embedded Web Stalker 'review'). In a manner comparable to the Art/Science ruptures of 'Distant Relations' (cf. Mute 10), audio-visual artists and designers have ignored or arbitrarily (mis-)assimilated traditions of innovative and experimental writing, while poetic avant-gardists have fiercely guarded their Cinderella-of-the-arts, holier-than-thou marginalisation, while arbitrarily (mis-)assimilating contemporary and, now, net art.

OK, so we have to do better, particularly in a field of cultural production which is constituted by the digital. If our understanding of the digital has been determined by our reading and writing of text, there must surely be greater interplay between artists whose work is and always has been text, and artists who are now working in media where text and its digital, programmable structures are enabling their recent engagements. (See Chris Cheek's 'must-reads' as a quick start card to encounter contemporary strains/factions in innovative/experimental writing). There seems to be a window of opportunity here. There is, for the record, a tradition of writing where the problematics of so-called 'advanced' literacy are continuously engaged. It's a long-standing tradition, running both parallel and counter to the mainstream. Recently it has been superbly and substantially documented, from the seminal moment of Mallarmé's "A Throw of the Dice will never Abolish Chance" in the two-volume anthology edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris, Poems for the Millennium (University of California Press, Berkeley 1995-98).

Paradoxically, as this window of opportunity opens and closes, as the cultural productions of previously analogue-only sensoria are progressively digitised, the already digital field of text gains access to modes of publication (or performance, if you prefer) which, although not regressively analogue, are nonetheless time-based. Textual movies, texts as movies, are now with us (and will even be tanked into Quicktime and other standards which underlie multi-media development). Language art already encompasses, for example, kinetic text (high bandwidth Grammatron 1.0 opens with a simple version of this, implemented through the html meta tag), holographic text (Eduardo Kac), 3D textual worlds (Jeffrey Shaw, Ladislao Pablo Györi) and other literary objects which are experienced as time-based. This will demand the development and application of new rhetorical tropes and figures to text which has previously been dominated - up to and including the implementation of link-node hypertext - by spatial structuring, by topographic rhetoric (though enclosed within the easily-granted linearities of print and narrative). Cinema will provide the privileged source of metaphors for these figures. To see what I mean, you should imagine a significant development in the kinds of textual transition and montage effects that we see in experimental typographic design, advertising and cinematic titling. These figures should quickly replace the hollow, passionless 'link' allowing time-based text art to emerge with a rich, cinematic rhetoric that is derived from the art of letters rather than exclusively or predominantly from visual art, music, or, as now, by default, from the arbitrary exigencies of the 'human-computer interface'. But this requires programming in time-based and socially-accessible media. While I have argued that most of the recognised 'advanced' characteristics of networked text are simply long-standing characteristics of literature, surrounded, as it were, by gaudy, html <BLINK> tags, there are certain potential aspects of text which are more specific to its implementation in networked, programmable media. These characteristics remain textual, but they are aspects of an art of language which still for the most part awaits realisation. They are, in a sense, proper to their media in that they would be all but impossible to implement in traditional forms of publication - a node-link hypertext can become a book and vice versa, but text generators require programmatons.

But this requires programming in time-based and socially-accessible media. While I have argued that most of the recognised 'advanced' characteristics of networked text are simply long-standing characteristics of literature, surrounded, as it were, by gaudy, html <BLINK> tags, there are certain potential aspects of text which are more specific to its implementation in networked, programmable media. These characteristics remain textual, but they are aspects of an art of language which still for the most part awaits realisation. They are, in a sense, proper to their media in that they would be all but impossible to implement in traditional forms of publication - a node-link hypertext can become a book and vice versa, but text generators require programmatons.

Specifically, there is the full Turing programmability of the media and the implications that this has for emergent forms of text-making, text-generation and literary objects in general. While there might seem to be a disjuncture here - between, say, the printed page and a literary chatterBot or poetic text-generator - in fact there is a continuum. The programmaton and its associated technologies have allowed writers to increase their intervention in the programming of a text progressively. When a writer takes over responsibility for the layout and design of the work, what is this but programming? The once-'new,' now-familiar technology of desk-top publishing allows writers to encode programmatic indications of suggested 'ways to read.' A text-generator, designed by the writer, simply takes the programming of such suggested ways to read a few stages further. As for the reader, when layout is even partially open-structure - as it is on the Web, for example, where the browser may override design choices - or when the source code of a text generator is accessible to a reader, then the hands-on writerly text, the text of active reader engagement, is realised after a fashion which extends or augments the inalienable interpretative functions of any text's consumers.

In time, there must come a recognition that programming (in the sense of prior, provisional writing) should be seen as a preferred model of Writing practice in any media, across the board. That's a Derridean, Ulmer-electerate big-'W'. Derrida still bears significant responsibility for our understanding of Writing as inscription on any surface, however complex, and, specifically, he early-on signalled the continuity of programming and Writing in a much-sited passage: '... thus we say 'writing' for all that gives rise to an inscription in general, whether it is literal or not and even if what it distributes in space is alien to the order of the voice: cinematography, choreography, of course, but also pictorial, musical, sculptural 'writing.' ... It is also in this sense that the biologist speaks of writing and pro-gram in relation to the most elementary processes of information with the living cell. And, finally, whether it has essential limits or not, the entire field covered by the cybernetic program will be the field of writing.' (Of Grammatology, trans. by G. Ch. Spivak, John Hopkins, Baltimore and London 1976, p. 9)

Programming is writing, writing recognised as prior and provisional, the detailed announcement of a performance which may soon take place (on the screen, in the mind), an indication of what to read and how. Programming will reconfigure the process of Writing and incorporate 'programming' in its technical sense, including the algorithms of text generators, textual movies, all the 'performance-design' publication and production aspects of text-making. Such a necessary inflection of language art practice may, perhaps, be further understood by contrast with the usual mis-assimilation of programming to writing, in which algorithms are seen as (new) 'tools' or (relatively insignificant) 'game-playing' devices at the casual disposal of the masterly writer, who then edits for publication. Instead, I say, writers are always already programmers (coders of inherently provisional scripts, subject to development, implementation and execution) and they must now be prepared to extend and deepen their practice in ways which embrace the continual - responsible, creative - reconfiguration of the delivery medium itself.

John CayleyXcayley AT shadoof.demon.co.ukXwww.demon.co.uk/eastfield/inWith thanks to Cris Cheek, I/O/D (for Web Stalker) and Lev Manovich.

Mute Books Orders

For Mute Books distribution contact Anagram Books

contact@anagrambooks.com

For online purchases visit anagrambooks.com